GREGORY the Natures of War FINAL May 2015

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

BC, De Los Estados Con Mayor Mortandad De Establecimientos Formales E Informales: INEGI Págs

AMLO: 6 estados Nueva alcaldesa pone estate quieto a Marina; concentran el 50% abre carpeta de de homicidios; investigación Pág. 3 entre ellos B.C. Página 9 http://MonitorEconomico.org Año VIII No. 2492 Martes 23 de marzo de 2021 BC, de los estados con mayor mortandad de establecimientos formales e informales: INEGI Págs. 4 y 5 Con 19 muertos diarios En plena crisis gobierno Hank Rhon se registra Escobedo da bienvenida de Tijuana prepara como candidato a la Semana Santa en B.C. aumento de impuesto a la gubernatura predial Pág. 2 Pág. 3 Pág. 9 /Economía MartesViernes 23 de marzo 1 de Abril de 20212011 Con 19 muertos diarios Escobedo da bienvenida a la Semana Santa en B.C. Por Luis Levar - Spring Brake. nianos a pesar de que se han mode- rado los avances. Apenas la semana pasada “la Secre- taría de Salud de Baja California pidió Con 363 muertos hasta el día señala- a la población no relajar las medidas do, el promedio de defunciones por de protección personal, porque el día se mantiene alto con 19 y apenas COVID -19 se mantiene activo, lo por debajo de las 22 que se registra- anterior una vez que se percibió ron en el mismo lapso de febrero. el pasado fin de semana una alta movilidad en bares, además la tasa A esto se debe agregar una campa- de reproducción efectiva del virus ña de vacunación lenta y desorgani- sigue en aumento”, según comuni- zada en la que a casi cuatro meses cado y ahora el mismo Alonso Pérez de que se anunció el inicio apenas fue parte del circo que anunció el se ha vacunado al 1.9 por ciento del “operativo”. -

FRATERNITIES Carstens

m _ edseodestt whe sepas the letter @t Maysee flaith Bad pinsw0 *ie aft Us enm tsee UP&U bwad wima-&imips1 ed t 000ta by er ber at whnne *ate fad both,"1110r110119"M mudt without. do usht net bb h h la W Wesatm112,0am has e the "am ofterams esm- * 'Dd him come W she said, and then been Ons in 4 bte" a fee-Illmmme a 4bvn--ai Mgea Sone of the maids of he the at thimrtu ofs0 ase a t be 1T. "evhgo de isn- temporary bath led a m dU- wh See waS esat to each m 1er et the esb- went to gli the mesenger Into the lsser who ghter-h&* 'a wwa hs' blood. wof I usaw m of the two tents of festval she added. bath made o she is ToU-q0-- a , bm his- **m7~TheIlulmef aemin cemnib- "And where Is-the'ma r you." Ie a towar the MareemA, BathM 944Wo baentehodAM LaVIARSIXh et PyM,aw atdtismA ~mmn-y. Adigagoswh.gnot tuigase with a, It was Yvette who answered ber. who stood u whSS anTraR TheI to a 100110 s-m 4101 yeaw ag& Some n"4aa 'Do not hear?' she erled, clapping at-the anddea fduf&panm. Vri mosame be itramarred M' aamhabemPto 8m-I he of a you wRi the harbt t t" eamtr Maes, No. of ts and Is her hands with pleasurw "His people are boy, slay YoeIldn 2, Hity, wt He bringing him up In triumph. Do you hear And at the wonhe preciptated Mise rec"neftd as me at the most sette aGd leg. -

FOIA) Document Clearinghouse in the World

This document is made available through the declassification efforts and research of John Greenewald, Jr., creator of: The Black Vault The Black Vault is the largest online Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) document clearinghouse in the world. The research efforts here are responsible for the declassification of hundreds of thousands of pages released by the U.S. Government & Military. Discover the Truth at: http://www.theblackvault.com Received Received Request ID Requester Name Organization Closed Date Final Disposition Request Description Mode Date 17-F-0001 Greenewald, John The Black Vault PAL 10/3/2016 11/4/2016 Granted/Denied in Part I respectfully request a copy of records, electronic or otherwise, of all contracts past and present, that the DOD / OSD / JS has had with the British PR firm Bell Pottinger. Bell Pottinger Private (legally BPP Communications Ltd.; informally Bell Pottinger) is a British multinational public relations and marketing company headquartered in London, United Kingdom. 17-F-0002 Palma, Bethania - PAL 10/3/2016 11/4/2016 Other Reasons - No Records Contracts with Bell Pottinger for information operations and psychological operations. (Date Range for Record Search: From 01/01/2007 To 12/31/2011) 17-F-0003 Greenewald, John The Black Vault Mail 10/3/2016 1/13/2017 Other Reasons - Not a proper FOIA I respectfully request a copy of the Intellipedia category index page for the following category: request for some other reason Nuclear Weapons Glossary 17-F-0004 Jackson, Brian - Mail 10/3/2016 - - I request a copy of any available documents related to Army Intelligence's participation in an FBI counterintelligence source operation beginning in about 1959, per David Wise book, "Cassidy's Run," under the following code names: ZYRKSEEZ SHOCKER I am also interested in obtaining Army Intelligence documents authorizing, as well as policy documents guiding, the use of an Army source in an FBI operation. -

Air and Space Power Journal: Winter 2009

SPINE AIR & SP A CE Winter 2009 Volume XXIII, No. 4 P OWER JOURN Directed Energy A Look to the Future Maj Gen David Scott, USAF Col David Robie, USAF A L , W Hybrid Warfare inter 2009 Something Old, Not Something New Hon. Robert Wilkie Preparing for Irregular Warfare The Future Ain’t What It Used to Be Col John D. Jogerst, USAF, Retired Achieving Balance Energy, Effectiveness, and Efficiency Col John B. Wissler, USAF US Nuclear Deterrence An Opportunity for President Obama to Lead by Example Group Capt Tim D. Q. Below, Royal Air Force 2009-4 Outside Cover.indd 1 10/27/09 8:54:50 AM SPINE Chief of Staff, US Air Force Gen Norton A. Schwartz Commander, Air Education and Training Command Gen Stephen R. Lorenz Commander, Air University Lt Gen Allen G. Peck http://www.af.mil Director, Air Force Research Institute Gen John A. Shaud, USAF, Retired Chief, Professional Journals Maj Darren K. Stanford Deputy Chief, Professional Journals Capt Lori Katowich Professional Staff http://www.aetc.randolph.af.mil Marvin W. Bassett, Contributing Editor Darlene H. Barnes, Editorial Assistant Steven C. Garst, Director of Art and Production Daniel M. Armstrong, Illustrator L. Susan Fair, Illustrator Ann Bailey, Prepress Production Manager The Air and Space Power Journal (ISSN 1554-2505), Air Force Recurring Publication 10-1, published quarterly, is the professional journal of the United States Air Force. It is designed to serve as an open forum for the http://www.au.af.mil presentation and stimulation of innovative thinking on military doctrine, strategy, force structure, readiness, and other matters of national defense. -

The North Korean Nuclear Crisis: Past Failures, Present Solutions

Saint Louis University Law Journal Volume 50 Number 2 A Tribute to the Honorable Michael A. Article 16 Wolff (Winter 2006) 2006 The North Korean Nuclear Crisis: Past Failures, Present Solutions Morse Tan The University of Texas at Austin School of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.slu.edu/lj Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Morse Tan, The North Korean Nuclear Crisis: Past Failures, Present Solutions, 50 St. Louis U. L.J. (2006). Available at: https://scholarship.law.slu.edu/lj/vol50/iss2/16 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Saint Louis University Law Journal by an authorized editor of Scholarship Commons. For more information, please contact Susie Lee. SAINT LOUIS UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF LAW THE NORTH KOREAN NUCLEAR CRISIS: PAST FAILURES, PRESENT SOLUTIONS MORSE TAN* ABSTRACT North Korea has recently announced that it has developed nuclear weapons and has pulled out of the six-party talks. These events do not emerge out of a vacuum, and this Article lends perspective through an interdisciplinary lens that seeks to grapple with the complexities and provide constructive approaches based on this well-researched understanding. This Article analyzes political, military, historical, legal and other angles of this international crisis. Past dealings with North Korea have been unfruitful because other nations do not recognize the ties between North Korean acts and its ideology and objectives. For a satisfactory resolution to the current crisis, South Korea and the United States must maintain sufficient deterrence, focus on multi-lateral and international avenues, and increase the negative and later positive incentives for North Korean compliance with its international obligations. -

FM 3-24.2. Tactics in Counterinsurgency

FM 3-24.2 (FM 90-8, FM 7-98) TACTICS IN COUNTERINSURGENCY APRIL 2009 DISTRIBUTION RESTRICTION: Approved for public release, distribution is unlimited. HEADQUARTERS DEPARTMENT OF THE ARMY This publication is available at Army Knowledge Online (www.us.army.mil) and General Dennis J. Reimer Training and Doctrine Digital Library at (www.train.army.mil). * FM 3-24.2 (FM 90-8, FM 7-98) Field Manual Headquarters Department of the Army No. 3-24.2 Washington, DC, 21 April 2009 Tactics in Counterinsurgency Contents Page PREFACE ................................................................................................................. viii INTRODUCTION ......................................................................................................... ix Chapter 1 OPERATIONAL ENVIRONMENT OF COUNTERINSURGENCY ........................... 1-1 Section I—OVERVIEW ............................................................................................. 1-1 Insurgency........................................................................................................... 1-1 Counterinsurgency .............................................................................................. 1-2 Influences on Current Operational Environments ............................................... 1-2 Section II—OPERATIONAL AND MISSION VARIABLES ..................................... 1-3 Operational Variables ......................................................................................... 1-3 Mission Variables ............................................................................................... -

Airpower in Three Wars

AIRPOWER IN THREE WARS GENERAL WILLIAM W. MOMYER USAF, RET. Reprint Edition EDITORS: MANAGING EDITOR - LT COL A. J. C. LAVALLE, MS TEXTUAL EDITOR - MAJOR JAMES C. GASTON, PHD ILLUSTRATED BY: LT COL A. J. C. LAVALLE Air University Press Maxwell Air Force Base, Alabama April 2003 Air University Library Cataloging Data Momyer, William W. Airpower in three wars / William W. Momyer ; managing editor, A. J. C. Lavalle ; textual editor, James C. Gaston ; illustrated by A. J. C. Lavalle–– Reprinted. p. ; cm. With a new preface. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 1-58566-116-3 1. Airpower. 2. World War, 1939–1945––Aerial operations. 3. Korean War. 1950–1953––Aerial operations. 4. Vietnamese Conflict, 1961–1975––Aerial oper- ations. 5. Momyer, William W. 6. Aeronautics, Military––United States. I. Title. II. Lavalle, A. J. C. (Arthur J. C.), 1940– III. Gaston, James C. 358.4/009/04––dc21 Disclaimer Opinions, conclusions, and recommendations expressed or implied within are solely those of the author and do not necessarily represent the views of Air University, the United States Air Force, the Department of Defense, or any other US government agency. Cleared for public release. Air University Press 131 West Shumacher Avenue Maxwell AFB AL 36112-6615 http://aupress.maxwell.af.mil ii TO . all those brave airmen who fought their battles in the skies for command of the air in World War II, Korea, and Vietnam. iii THIS PAGE INTENTIONALLY LEFT BLANK PREFACE 2003 When I received the request to update my 1978 foreword to this book, I thought it might be useful to give my perspective of some aspects on the employment of airpower in the Persian Gulf War, the Air War over Serbia (Operation Allied Force), and the war in Afghanistan (Operation Enduring Freedom). -

Vietnam War US Army Video Log Michael Momparler Born

Video Log Michael Momparler Vietnam War U.S. Army Born: 03/05/1947 Interviewed on 11/20/2012 Interviewed by: George Jones 00:00:00 Introduction 00:00:23 Michael Momparler’s highest rank was 1st Lieutenant. 00:00:35 Momparler served in III Corps in Vietnam 00:00:45 Momparler was living in College Point, NY when he enlisted in the Army on 4/18/1966. He joined because he was a wild teenager with legal problems and few other options 00:01:45 Momparler discusses first days in the U.S. Army and his thoughts about the experience and the military experiences of other family members; specifically a cousin who suffered the loss of six fellow Marines. 00:03:23 Momparler discusses basic training experiences like using monkey bars, the mile run, and KP. 00:04:40 Momparler discusses being selected for Officer Candidate School - OCS. Mentions the testing and that he was encouraged to tell the interviewing officer that the war in Vietnam should be escalated. Entered OCS at age 19. 00:05:50 Momparler transition from basic training to advanced infrantry training to OCS. 00:06:24 Momparler discusses experiences with the M-14, M-15, and M-16 rifles. 00:07:00 Momparler discusses the experience of Officer Candidate School. 00:10:32 Momparler mentions that one of his commanding officers was in the Bay of Pigs invasion. Discusses the amount of combat experience, or Vietnam experience of his commanding officers at OCS. 00:11:00 Momparler discusses how OCS candidates used the OCS experience to limit their amount of time in the Army or avoid having to serve in Vietnam. -

Canadian Military Journal, Issue 14, No 1

Vol. 14, No. 1, Winter 2013 CONTENTS 3 EDITOR’S CORNER 6 LETTER TO THE EDITOR FUTURE OPERATIONS 7 WHAT IS AN ARMED NON-STATE Actor (ANSA)? by James W. Moore Cover AFGHANISTAN RETROSPECTIVE The First of the Ten Thousand John Rutherford and the Bomber 19 “WAS IT worth IT?” CANADIAN INTERVENTION IN AFGHANISTAN Command Museum of Canada AND Perceptions OF SUccess AND FAILURE by Sean Maloney CANADA-UNITED STATES RELATIONS 32 SECURITY THREAts AT THE CANADa-UNITED STATES BORDER: A QUEST FOR IMPOSSIBLE PERFECTION by François Gaudreault LESSONS FROM THE PAST 41 PRESIDENT DWIGHT D. Eisenhower’S FArewell ADDRESS to THE NATION, 17 JANUARY 1961 ~ AN ANALYSIS OF COMpetinG TRUTH CLAIMS AND its RELEVANCE TODAY by Garrett Lawless and A.G. Dizboni 47 BREAKING THE STALEMATE: AMphibioUS WARFARE DURING THE FUTURE OPERATIONS WAR OF 1812 by Jean-Francois Lebeau VIEWS AND OPINIONS 55 NothinG New UNDER THE SUN TZU: TIMELESS PRINCIPLES OF THE OperATIONAL Art OF WAR by Jacques P. Olivier 60 A CANADIAN REMEMBRANCE TRAIL FOR THE CENTENNIAL OF THE GREAT WAR? by Pascal Marcotte COMMENTARY 64 DEFENCE ProcUREMENT by Martin Shadwick 68 BOOK REVIEWS AFGHANISTAN RETROSPECTIVE Canadian Military Journal / Revue militaire canadienne is the official professional journal of the Canadian Armed Forces and the Department of National Defence. It is published quarterly under authority of the Minister of National Defence. Opinions expressed or implied in this publication are those of the author, and do not necessarily represent the views of the Department of National Defence, the Canadian Forces, Canadian Military Journal, or any agency of the Government of Canada. -

Tet 1968 Draft 2

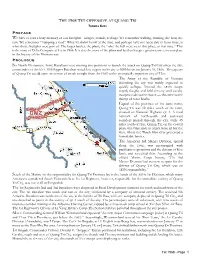

THOMAS KJOS We have at least a hazy memory of our firefights - images, sounds, feelings. We remember walking, running, the heat, the rain. We remember “humping a load.” What we didn’t know at the time, and perhaps have not been able to learn since, is what those firefights were part of. The larger battles, the plans, the “why the hell were we in that place, at that time.” This is the story of Delta Company at Tet in 1968. It is also the story of the plans and battles that give greater context to our place in the history of the Vietnam war. Six North Vietnamese Army Battalions were moving into positions to launch the attack on Quang Tri City when the elite commandos of the NVA 10th Sapper Battalion struck key targets in the city at 0200 hours on January 31, 1968. The capture of Quang Tri would open an avenue of attack straight from the DMZ to the strategically important city of Hue. The Army of the Republic of Vietnam defending the city was widely expected to quickly collapse. Instead, the ARVN troops stayed, fought, and held the city until cavalry troopers rode to the rescue — this time to the thump of rotor blades. Capital of the province of the same name, Quang Tri was 12 miles south of the DMZ, situated on National Highway QL 1. A road network of north-south and east-west corridors passed through the city. Only 45 miles north of Hue, Quang Tri, on the coastal plain, was vulnerable to attack from all but the west, where the Thach Han river presented a formidable barrier. -

2013 6 Chem News.Pdf

P a g e | 1 CBRNE-Terrorism Newsletter – December 2013 www.cbrne-terrorism-newsletter.com P a g e | 2 CBRNE-Terrorism Newsletter – December 2013 . Virtual HUMINT™ vs. Terrorist CBRN Capabilities Source: http://www.cbrneportal.com/virtual-humint-vs-terrorist-cbrn-capabilities/ Chemical, Biological, Radiological and Nuclear open sources and, especially, deep web weapons are the “game-changers” that sources: jihadists all over the world aspire to get their A jihadist forum member posted hands on. Terrorist organizations and other approximately ten files containing non-state actors continue to seek bona fide presentations of biology courses in a WMDs in order to further their goals in most secure forum, stating that they “would be of macabre ways – if “terror” is the goal, CBRN is benefit to the fighters.” In late September Syrian regime forces seized several tunnels belonging to the Syrian rebels in the city of Tadmur, a suburb of Aleppo. Tubes with tablets of Phostoxin (aluminum phosphide) were discovered in the raid, in addition to IEDs, IED precursors and foreign car license plates. In mid-September, several Turkish websites published information about the indictment brought against the six members of Jabhat al-Nusra (JN) and Ahrar al-Sham. Five were Turkish citizens and one a Syrian, named Haytham surely the ideal means. Qassab. The Syrian was charged with The ubiquity and efficiency of internet means being a member of a terrorist organization that any piece of CBRN knowledge published and attempting to acquire weapons for a on terrorist online networks is immediately terrorist organization. Turkish authorities available to all terrorists everywhere. -

Untitled Essay, 1946 Intelligence Overload These Days

CONTENTS OVERVIEW ................................................................. vi INTRODUCTION: The Name of the Game: Let’s Define Our Terms ........... vii CHAPTER 1 HOW TO DECEIVE: Principles & Process 1.1 Deception as Applied Psychology....................................... 1 1.2 The Basic Principle: Naturalness........................................ 6 1.3 The Structure of Deception ............................................ 7 1.4 The Process of Deception............................................ 13 CHAPTER 2 INTERFACE: Deceiver versus Detective 2.1 Weaving the Web .................................................. 16 2.2 Unraveling the Web................................................. 17 CHAPTER 3 HOW TO DETECT: 10 General Principles 3.1 Cognitive Biases that Inhibit Detection .................................. 20 3.2 Overcoming Information Overload...................................... 20 3.3 The Analysts: Minimalists versus Compleatists ........................... 22 3.4 The Analyst’s Advantage............................................. 23 3.5 Categories ........................................................ 24 3.6 Know Your Enemy: Empathy & Inference................................ 32 3.7 Channels ......................................................... 34 3.8 Senses & Sensors.................................................. 35 3.9 Cultural Factors.................................................... 39 3.10 Asymmetries: Technological & Cognitive ................................ 40 CHAPTER 4 HOW TO DETECT: 20