Home Front Recall Booklet

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Royal Air Force Historical Society Journal 29

ROYAL AIR FORCE HISTORICAL SOCIETY JOURNAL 29 2 The opinions expressed in this publication are those of the contributors concerned and are not necessarily those held by the Royal Air Force Historical Society. Copyright 2003: Royal Air Force Historical Society First published in the UK in 2003 by the Royal Air Force Historical Society All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission from the Publisher in writing. ISSN 1361-4231 Typeset by Creative Associates 115 Magdalen Road Oxford OX4 1RS Printed by Advance Book Printing Unit 9 Northmoor Park Church Road Northmoor OX29 5UH 3 CONTENTS BATTLE OF BRITAIN DAY. Address by Dr Alfred Price at the 5 AGM held on 12th June 2002 WHAT WAS THE IMPACT OF THE LUFTWAFFE’S ‘TIP 24 AND RUN’ BOMBING ATTACKS, MARCH 1942-JUNE 1943? A winning British Two Air Forces Award paper by Sqn Ldr Chris Goss SUMMARY OF THE MINUTES OF THE SIXTEENTH 52 ANNUAL GENERAL MEETING HELD IN THE ROYAL AIR FORCE CLUB ON 12th JUNE 2002 ON THE GROUND BUT ON THE AIR by Charles Mitchell 55 ST-OMER APPEAL UPDATE by Air Cdre Peter Dye 59 LIFE IN THE SHADOWS by Sqn Ldr Stanley Booker 62 THE MUNICIPAL LIAISON SCHEME by Wg Cdr C G Jefford 76 BOOK REVIEWS. 80 4 ROYAL AIR FORCE HISTORICAL SOCIETY President Marshal of the Royal Air Force Sir Michael Beetham GCB CBE DFC AFC Vice-President Air Marshal Sir Frederick Sowrey KCB CBE AFC Committee Chairman Air Vice-Marshal -

Scottish Birds 37:3 (2017)

Contents Scottish Birds 37:3 (2017) 194 President’s Foreword J. Main PAPERS 195 Potential occurrence of the Long-tailed Skua subspecies Stercorarius longicaudus pallescens in Scotland C.J. McInerny & R.Y. McGowan 202 Amendments to The Scottish List: species and subspecies The Scottish Birds Records Committee 205 The status of the Pink-footed Goose at Cameron Reservoir, Fife from 1991/92 to 2015/16: the importance of regular monitoring A.W. Brown 216 Montagu’s Harrier breeding in Scotland - some observations on the historical records from the 1950s in Perthshire R.L. McMillan SHORT NOTES 221 Scotland’s Bean Geese and the spring 2017 migration C. Mitchell, L. Griffin, A. MacIver & B. Minshull 224 Scoters in Fife N. Elkins OBITUARIES 226 Sandy Anderson (1927–2017) A. Duncan & M. Gorman 227 Lance Leonard Joseph Vick (1938–2017) I. Andrews, J. Ballantyne & K. Bowler ARTICLES, NEWS & VIEWS 229 The conservation impacts of intensifying grouse moor management P.S. Thompson & J.D. Wilson 236 NEWS AND NOTICES 241 Memories of the three St Kilda visitors in July 1956 D.I.M. Wallace, D.G. Andrew & D. Wilson 244 Where have all the Merlins gone? A lament for the Lammermuirs A.W. Barker, I.R. Poxton & A. Heavisides 251 Gannets at St Abb’s Head and Bass Rock J. Cleaver 254 BOOK REVIEWS 256 RINGERS' ROUNDUP Iain Livingstone 261 The identification of an interesting Richard’s Pipit on Fair Isle in June 2016 I.J. Andrews 266 ‘Canada Geese’ from Canada: do we see vagrants of wild birds in Scotland? J. Steele & J. -

House of Commons Official Report

Monday Volume 650 26 November 2018 No. 212 HOUSE OF COMMONS OFFICIAL REPORT PARLIAMENTARY DEBATES (HANSARD) Monday 26 November 2018 © Parliamentary Copyright House of Commons 2018 This publication may be reproduced under the terms of the Open Parliament licence, which is published at www.parliament.uk/site-information/copyright/. HER MAJESTY’S GOVERNMENT MEMBERS OF THE CABINET (FORMED BY THE RT HON. THERESA MAY, MP, JUNE 2017) PRIME MINISTER,FIRST LORD OF THE TREASURY AND MINISTER FOR THE CIVIL SERVICE—The Rt Hon. Theresa May, MP CHANCELLOR OF THE DUCHY OF LANCASTER AND MINISTER FOR THE CABINET OFFICE—The Rt Hon. David Lidington, MP CHANCELLOR OF THE EXCHEQUER—The Rt Hon. Philip Hammond, MP SECRETARY OF STATE FOR THE HOME DEPARTMENT—The Rt Hon. Sajid Javid, MP SECRETARY OF STATE FOR FOREIGN AND COMMONWEALTH AFFAIRS—The Rt. Hon Jeremy Hunt, MP SECRETARY OF STATE FOR EXITING THE EUROPEAN UNION—The Rt Hon. Stephen Barclay, MP SECRETARY OF STATE FOR DEFENCE—The Rt Hon. Gavin Williamson, MP LORD CHANCELLOR AND SECRETARY OF STATE FOR JUSTICE—The Rt Hon. David Gauke, MP SECRETARY OF STATE FOR HEALTH AND SOCIAL CARE—The Rt Hon. Matt Hancock, MP SECRETARY OF STATE FOR BUSINESS,ENERGY AND INDUSTRIAL STRATEGY—The Rt Hon. Greg Clark, MP SECRETARY OF STATE FOR INTERNATIONAL TRADE AND PRESIDENT OF THE BOARD OF TRADE—The Rt Hon. Liam Fox, MP SECRETARY OF STATE FOR WORK AND PENSIONS—The Rt Hon. Amber Rudd, MP SECRETARY OF STATE FOR EDUCATION—The Rt Hon. Damian Hinds, MP SECRETARY OF STATE FOR ENVIRONMENT,FOOD AND RURAL AFFAIRS—The Rt Hon. -

Puffin Cottage BROUGH, THURSO, CAITHNESS, KW14 8YE 01463 211 116 “

Puffin Cottage BROUGH, THURSO, CAITHNESS, KW14 8YE 01463 211 116 “... an ideal location for outdoor activities such as Fishing, horse riding, cycling, kayaking and walking ...” ocated on the road to Dunnet Head, the Head, the most northerly point on the UK mainland, Inverness, approximately two and a half hours drive small hamlet of Brough is a very popular making it an ideal location for outdoor activities away via the A9 trunk road, is one of the fastest growing and attractive residential neighbourhood. such as fishing, horse riding, cycling, kayaking and cities in Europe and provides a range of retail parks The property is very well located being walking. The village of Dunnet with its hotel and along with excellent cultural, educational, entertainment only ten minutes drive from John o’Groats, community hall is also close by. and medical facilities. fifteen minutes from Thurso and twenty-five Lminutes from Wick. The Orkney ferry is five minutes Thurso has many facilities including supermarkets and The Scottish Highlands are a magnet for lovers of drive away making it an excellent stop over to and a railway station with regular services to Inverness and the outdoors and the ruggedness of the north-west from Orkney. connections to the rest of the UK. Wick Airport has daily Highlands, often referred to as the last great wilderness flights to Edinburgh and Aberdeen where domestic and in Europe, boasts some of the most beautiful beaches The property is close to the RSPB-owned Dunnet international flights are available. and mountains in Scotland. Dunnet Bay Winter Sunshine, Dunnet Head Lighthouse view to Hoy, Castle of Mey, Dwarwick Pier Storm, Harrow Harbour near Mey and Dunnet Bay towards Dunnet Head cEwan Fraser Legal are delighted to offer plan family room has bay windows as a lovely feature completes the luxurious feel to this lovely home. -

Downloadable Content the Supermarine

AIRFRAME & MINIATURE No.12 The Supermarine Spitfire Part 1 (Merlin-powered) including the Seafire Downloadable Content v1.0 August 2018 II Airframe & Miniature No.12 Spitfire – Foreign Service Foreign Service Depot, where it was scrapped around 1968. One other Spitfire went to Argentina, that being PR Mk XI PL972, which was sold back to Vickers Argentina in March 1947, fitted with three F.24 cameras with The only official interest in the Spitfire from the 8in focal length lens, a 170Imp. Gal ventral tank Argentine Air Force (Fuerca Aerea Argentina) was and two wing tanks. In this form it was bought by an attempt to buy two-seat T Mk 9s in the 1950s, James and Jack Storey Aerial Photography Com- PR Mk XI, LV-NMZ with but in the end they went ahead and bought Fiat pany and taken by James Storey (an ex-RAF Flt Lt) a 170Imp. Gal. slipper G.55Bs instead. F Mk IXc BS116 was allocated to on the 15th April 1947. After being issued with tank installed, it also had the Fuerca Aerea Argentina, but this allocation was the CofA it was flown to Argentina via London, additional fuel in the cancelled and the airframe scrapped by the RAF Gibraltar, Dakar, Brazil, Rio de Janeiro, Montevi- wings and fuselage before it was ever sent. deo and finally Buenos Aires, arriving at Morón airport on the 7th May 1947 (the exhausts had burnt out en route and were replaced with those taken from JF275). Storey hoped to gain an aerial mapping contract from the Argentine Government but on arrival was told that his ‘contract’ was not recognised and that his services were not required. -

Caithness County Council

Caithness County Council RECORDS’ IDENTITY STATEMENT Reference number: CC Alternative reference number: Title: Caithness County Council Dates of creation: 1720-1975 Level of description: Fonds Extent: 10 bays of shelving Format: Mainly paper RECORDS’ CONTEXT Name of creators: Caithness County Council Administrative history: 1889-1930 County Councils were established under the Local Government (Scotland) Act 1889. They assumed the powers of the Commissioners of Supply, and of Parochial Boards, excluding those in Burghs, under the Public Health Acts. The County Councils also assumed the powers of the County Road Trusts, and as a consequence were obliged to appoint County Road Boards. Powers of the former Police Committees of the Commissioners were transferred to Standing Joint Committees, composed of County Councillors, Commissioners and the Sheriff of the county. They acted as the police committee of the counties - the executive bodies for the administration of police. The Act thus entrusted to the new County Councils most existing local government functions outwith the burghs except the poor law, education, mental health and licensing. Each county was divided into districts administered by a District Committee of County Councillors. Funded directly by the County Councils, the District Committees were responsible for roads, housing, water supply and public health. Nucleus: The Nuclear and Caithness Archive 1 Provision was also made for the creation of Special Districts to be responsible for the provision of services including water supply, drainage, lighting and scavenging. 1930-1975 The Local Government Act (Scotland) 1929 abolished the District Committees and Parish Councils and transferred their powers and duties to the County Councils and District Councils (see CC/6). -

Midnight Train to Georgemas Report Final 08-12-2017

Midnight Train to Georgemas 08/12/2017 Reference number 105983 MIDNIGHT TRAIN TO GEORGEMAS MIDNIGHT TRAIN TO GEORGEMAS MIDNIGHT TRAIN TO GEORGEMAS IDENTIFICATION TABLE Client/Project owner HITRANS Project Midnight Train to Georgemas Study Midnight Train to Georgemas Type of document Report Date 08/12/2017 File name Midnight Train to Georgemas Report v5 Reference number 105983 Number of pages 57 APPROVAL Version Name Position Date Modifications Claire Mackay Principal Author 03/07/2017 James Consultant Jackson David Project 1 Connolly, Checked Director 24/07/2017 by Alan Director Beswick Approved David Project 24/07/2017 by Connolly Director James Principal Author 21/11/2017 Jackson Consultant Alan Modifications Director Beswick to service Checked 2 21/11/2017 costs and by Project David demand Director Connolly forecasts Approved David Project 21/11/2017 by Connolly Director James Principal Author 08/12/2017 Jackson Consultant Alan Director Beswick Checked Final client 3 08/12/2017 by Project comments David Director Connolly Approved David Project 08/12/2017 by Connolly Director TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION 6 2. BACKGROUND INFORMATION 6 2.1 EXISTING COACH AND RAIL SERVICES 6 2.2 CALEDONIAN SLEEPER 7 2.3 CAR -BASED TRAVEL TO /FROM THE CAITHNESS /O RKNEY AREA 8 2.4 EXISTING FERRY SERVICES AND POTENTIAL CHANGES TO THESE 9 2.5 AIR SERVICES TO ORKNEY AND WICK 10 2.6 MOBILE PHONE -BASED ESTIMATES OF CURRENT TRAVEL PATTERNS 11 3. STAKEHOLDER CONSULTATION 14 4. PROBLEMS/ISSUES 14 4.2 CONSTRAINTS 16 4.3 RISKS : 16 5. OPPORTUNITIES 17 6. SLEEPER OPERATIONS 19 6.1 INTRODUCTION 19 6.2 SERVICE DESCRIPTION & ROUTING OPTIONS 19 6.3 MIXED TRAIN OPERATION 22 6.4 TRACTION & ROLLING STOCK OPTIONS 25 6.5 TIMETABLE PLANNING 32 7. -

North Hill in World War II Minehead, Somerset SCHOOLS RESOURCE PACK for Key Stages 2 & 3

BACKGROUND READING AND TEACHER SUPPORT & PREPARATION North Hill in World War II Minehead, Somerset SCHOOLS RESOURCE PACK for Key Stages 2 & 3 SECTION 1 – NORTH HILL BEFORE AND DURING WORLD WAR 2 P1 -3 SECTION 2 – TANKS IN WORLD WAR 2 P4-5 SECTION 3 – TANK TRAINING IN WORLD WAR 2 P6-9 SECTION 4 – RADAR IN WORLD WAR 2, NORTH HILL RADAR STATION P10-13 SOURCES, VISUALS AND LINKS – TANK BACKGROUND READING AND TASKS P14-15 TEACHER SUPPORT AND PREPARATION P16 -20 _______________________________________________________________________________________________ BACKGROUND READING SECTION 1 – NORTH HILL BEFORE AND DURING WORLD WAR 2 WORLD WAR 2, 1939 -45 On September 1st 1939 Nazi Germany invaded Poland, two days later the British Prime Minister, Neville Chamberlain, declared war on Germany. Britain joined with France and Poland, followed by the countries of the British Empire and Commonwealth. This group came to be known as ‘the Allies’. In 1941 they were joined by America and Canada, whose armies came to Minehead to train. Britain was badly-equipped for war and there was an urgent need for military training. Existing facilities were outdated and land for tank training was in short supply. North Hill became one of five major new tank training grounds in the country. NORTH HILL AS A MILITARY SITE During the Iron Age (700 BC – 43 AD), and the reigns of Henry VIII and Elizabeth I North Hill was considered an important military site. A beacon was set up above Selworthy in 1555, and in the late 1800s a large military training camp was established. The area continued as a training ground right up to the First World War. -

Caithness and Sutherland Proposed Local Development Plan Committee Version November, 2015

Caithness and Sutherland Proposed Local Development Plan Committee Version November, 2015 Proposed CaSPlan The Highland Council Foreword Foreword Foreword to be added after PDI committee meeting The Highland Council Proposed CaSPlan About this Proposed Plan About this Proposed Plan The Caithness and Sutherland Local Development Plan (CaSPlan) is the second of three new area local development plans that, along with the Highland-wide Local Development Plan (HwLDP) and Supplementary Guidance, will form the Highland Council’s Development Plan that guides future development in Highland. The Plan covers the area shown on the Strategy Map on page 3). CaSPlan focuses on where development should and should not occur in the Caithness and Sutherland area over the next 10-20 years. Along the north coast the Pilot Marine Spatial Plan for the Pentland Firth and Orkney Waters will also influence what happens in the area. This Proposed Plan is the third stage in the plan preparation process. It has been approved by the Council as its settled view on where and how growth should be delivered in Caithness and Sutherland. However, it is a consultation document which means you can tell us what you think about it. It will be of particular interest to people who live, work or invest in the Caithness and Sutherland area. In preparing this Proposed Plan, the Highland Council have held various consultations. These included the development of a North Highland Onshore Vision to support growth of the marine renewables sector, Charrettes in Wick and Thurso to prepare whole-town visions and a Call for Sites and Ideas, all followed by a Main Issues Report and Additional Sites and Issues consultation. -

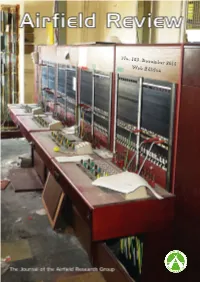

No. 153 December 2016 Web Edition

No. 153 December 2016 Web Edition Airfield Research Group Ltd Registered in England and Wales | Company Registration Number: 08931493 | Registered Charity Number: 1157924 Registered Office: 6 Renhold Road, Wilden, Bedford, MK44 2QA To advance the education of the general public by carrying out research into, and maintaining records of, military and civilian airfields and related infrastructure, both current and historic, anywhere in the world All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced in any form, by any means, without the prior permission in writing of the author and copyright holder. Any information subsequently used must credit both the author and Airfield Review / ARG Ltd. T HE ARG MA N ag E M EN T TE am Directors Chairman Paul Francis [email protected] 07972 474368 Finance Director Norman Brice [email protected] Director Peter Howarth [email protected] 01234 771452 Director Noel Ryan [email protected] Company Secretary Peter Howarth [email protected] 01234 771452 Officers Membership Secretary & Roadshow Coordinator Jayne Wright [email protected] 0114 283 8049 Archive & Collections Manager Paul Bellamy [email protected] Visits Manager Laurie Kennard [email protected] 07970 160946 Health & Safety Officer Jeff Hawley [email protected] Media and PR Jeff Hawley [email protected] Airfield Review Editor Graham Crisp [email protected] 07970 745571 Roundup & Memorials Coordinator Peter Kirk [email protected] C ON T EN T S I NFO rmati ON A ND RE G UL ar S F E at U R ES Information and Notices .................................................1 AW Hawksley Ltd and the Factory at Brockworth ..... -

German WW2 ECM (Electronic Countermeasures)

- • - • - - • - - • • • • • • - • - - • • • - • • • • • - • German WW2 ECM (Electronic Countermeasures) Adam Farson VA7OJ 17 October 2013 NSARC – German WW2 ECM 1 Glossary of terms - • - • - - • - - • • • • • • - • - - • • • - • • • • • - • Common acronyms: SIGINT: SIGnals INTelligence COMINT: COMmunications INTelligence (communications between people or entities) ELINT: ELectronics INTelligence (electronic signals not directly used in communications e.g. radar, radio-navigation) ECM: Electronic CounterMeasures ECCM: Electronic Counter-CounterMeasures EW: Electronic Warfare (encompasses all the above) System designators: AI: Airborne Interception radar ASV: Air to Surface Vessel radar CD: Coastal Defence radar CH: Chain Home radar (CHL = Chain Home Low) D/F: Direction Finding Huff-Duff: High Frequency D/F H2S: British 3 GHz radar with PPI (plan-position indicator) display (possible abbreviation for “Home Sweet Home”) H2X: US 10 GHz variant of H2S 17 October 2013 NSARC – German WW2 ECM 2 Scope of presentation - • - • - - • - - • • • • • • - • - - • • • - • • • • • - • Detection, interception & analysis Communications vs. radar monitoring Direction-finding Examples of COMINT, ELINT, SIGINT sites Radar detection VHF/UHF & microwave radar detectors & threat receivers Land, shipboard & airborne systems Notes on German microwave technology Jamming & spoofing: Radio communications: HF, VHF Navaids: GEE, OBOE Radar: VHF/UHF, 3 GHz, 10 GHz Equipment examples A case history: Operation Channel Dash (Cerberus) 17 October -

Erection of One 500 Kw Wind Turbine at 550 M of Taigh Na Muir, Dunnet By

THE HIGHLAND COUNCIL Agenda Item 6.2 NORTH PLANNING APPLICATIONS COMMITTEE – Report No PLN/048/13 21 May 2013 12/03638/FUL : R R Mackay ·& Company Limited Land 550M NW of Tigh na Muir, Dunnet Report by Area Planning Manager North SUMMARY Description: Erection of 1 no 500kW wind turbine with a height to blade tip of 79.6m, 55m to hub and a rotor diameter of 48m and ancillary works at Land 550M NW of Tigh na Muir, Dunnet. Recommendation : REFUSE Ward : 04 Landward Caithness Development category : Local Pre-determination Hearing : none Reason referred to commitee ; Local member request 1. PROPOSED DEVELOPMENT 1.1 Application is made in detail for the erection of 1 no. turbine with a height to blade tip of 79.6 metres, a height to hub of 55 metres and a rotor diameter of 48 metres. The associated infrastructure includes turbine foundations; crane hardstanding; pole mounted transformer and associated cabling and an upgrading and lengthening of an existing 540 metre access track to site from the edge of the exiting private access area to ‘Tigh na Muir’. 1.2 A formal Screening Opinion was issued on 08 September 2011, advising that an Environmental Impact Assessment was not required. 1.3 It is proposed that the turbine and construction components will utilise the A836 Castletown to John O’Groats public road and the existing farm access. 1.4 The applicant has provided a number of supporting documents including a Supporting Statement, Site and Viewpoint Map, Photomontages, an Ornithology Appraisal, Technical Appendix, and Surveys. 1.5 Variations: Otter Survey Report Received 23 October 2012.