The Evolution of Traditional Shipping in China

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pusat-Damai.Pdf

Model A.3 - KPU DAFTAR PEMILIH TETAP PEMILIHAN UMUM ANGGOTA DPR, DPD, DPRD PROVINSI DAN DPRD KABUPATEN / KOTA TAHUN 2014 PROVINSI : KALIMANTAN BARAT KECAMATAN : PARINDU KABUPATEN/KOTA 1) : SANGGAU DESA/KELURAHAN : PUSAT DAMAI TPS : 001 Status Jenis No Tanggal Alamat No KK NIK Nama Tempat Lahir Umur Perkawinan Kelamin Keterangan 2) Urut Lahir B/S/P L/P Jalan / Dusun Rt Rw 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 1 6103090603080016 6103091905550001 F AHUI BOYOK 19-05-1955 58 S L - 000 000 2 6103091003050583 6103092004690001 MARTINVS BODOK 20-04-1969 44 P L - 000 000 3 6103091003050858 6103090107620043 GEDION YON SANGGAU 01-07-1962 51 P L - 000 000 4 6103091003050858 6103094107630005 ELISABFT ELIS SANGGAU 01-07-1963 50 P P - 000 000 5 6103091003050858 6103090104850001 LORENSIUS SANGGAU 01-04-1985 29 P L - 000 000 6 6103091003050858 6103096312910001 ANGGELA SUSI SANGGAU 23-12-1991 22 S P - 000 000 7 6103091003050871 6103095004540001 REGINA PAYONG SANGGAU 10-04-1954 59 P P - 000 000 8 6103091003050871 6103096906880003 BENEDIKTA JUNIARTI SANGGAU 29-06-1988 25 P P - 000 000 9 6103091003050874 6103091904880001 VINSENSIUS SISWONO SAMGGAV 19-04-1988 25 P L - 000 000 10 6103091003050878 6103090912760001 ADRIANUS SANGGAU 09-12-1976 37 B L - 000 000 11 6103091003050878 6103095811770001 ADITA TAMAN PONTIANAK 18-11-1977 36 P P - 000 000 12 6103091003051195 6103090509700001 REGURLI SIKAIT SPD SANGGAU 05-09-1970 43 B L - 000 000 13 6103091003051195 6103094806710001 ASAISPD LANDAK 08-06-1971 42 B P - 000 000 14 6103091510080014 6103090202480001 BONG NYUK ICHIONG -

CAT CRAZY, TRI FI and Other Multihull Comparisons by Jim Brown

CAT CRAZY, TRI FI And Other Multihull Comparisons By Jim Brown “There is nothing, absolutely nothing, quite so much worth doing as simply messing about in…” Multihulls! That paraphrased quote is pilfered for the most part from Ratty, the revered rodent in Kenneth Grahame’s venerated tale “The Wind in the Willows.” Of course, Grahame and Ratty said it of ordinary boats, and neither would have, even could have, said it of multihulls. But if Brown had been the author instead of Grahame, his character Ratty might have said something like, “There is nothing, absolutely nothing quite so creative as screwing around with multihulls.” By “screwing around,” Ratty would have spoken literally, meaning to conceive, gestate, whelp, wean and release upon the Earth’s fluid interface one’s very own flesh and blood multihulls. And that’, impatient reader, is what this appendix is about, so like most appendices reading it is strictly optional. In that you are reading on, please be prepared for some sacrilege. Suggesting there is something divine about boat design and construction I will try to trace multihull origins by expanding on the theorem expressed by my late friend Walt Glaser who said (in Chapter 1 of my memoir, “Among the Multihulls,”), “A man builds a boat to make up for the fact that he can’t build a baby… What else can a guy produce with his own body that so closely simulates a living thing?” It took me many years of both messing about in and screwing around with boats to apprehend this aspect of watercraft, and I admit that it still takes quite a stretch for me to accept the notion. -

Fitting the Unstayed Mast Rig To

ITTING THE UNSTAYED MAST RIG TO YOUR BOAT SOME POPULAR QUESTIONS ANSWERED: - . Will it suit any boat of any hull shape? - Yes, and will particularly aid shallow draft hulls of low ballast ratio as the flexibility of the mast reduces heeling in all conditions. 2. Can it be fitted to multihulls? - Yes, Trimaran installations are similar to monohulls. Catamarans can either have modified bridge decks to obtain sufficient bury of mast or fit a smaller mast in each hull. 3. Can I use my existing stayed rig mast?- No, with the exception of some solid timber Gaff rig masts. 4. Does the mast have to be keel stepped? - Preferably, but it can be fitted in a deck tabernacle. 5. Where is the mast stepped? - Approximately 2 to 4 feet forward of a stayed mast postion. 6. Does it have to be near a bulkhead? - No, as the load transmitted to the deck is not enormous. 7. What structural modifications will I have to make to my boat? - Probably increase the deck strength at the mast by adding:- - for GRP boats more layup of C.S. matt which will be hidden by the head lining under the deck. - for steel, alloy, ferrocement, timber boats, add a deck beam. The mast step only needs to be firmly secured to the keel and no extra reinforcement is necessary to be the boat's keel. - for sheeting to the pushpit, possibly, add a bracing strut across the existing tube, such as a sheet track. 8. How many sails and of what area should be used? - As a general rule:- For boats up to 30 ft., one sail is more ideal. -

Download (1MB)

DaftarIsi Halaman Kata Pengantar . Daftar Isi ii Kebijakan Komunikasi Pemasaran Terpadu Rokok Ds untuk Meningkatkan Loyalitas Merek Konsumen Ds Usia SMU Di Bandung 1 - 15 Iwan Setiawan dan Budiarto Subroto Vernakularitas Balai Adat Suku Dayak Bukit Sebagai Destinasi dan Obyek Wisata Budaya Di Kalimantan Selatan 16 - 26 Bani Noor Muchamad dan Nugroho B Sukamdani Analisa Trend Dan Faktor Yang Mempengaruhi Pendapatan Negara di Asia Tenggara 27 - 36 Bemard Hasibuan Rumah Adat Bugis Propinsi Sulawesi Selatan Dalam Perspektif Destinasi Pariwisata 37 - 46 Hartawan dan Nindyo Soewarno Analisis Altman Z-Score Dalam Memprediksi Kondisi Keuangan Perusahaan Serta Pengaruhnya Terhadap Price To Book Value 47 - 64 Djong Riky dan Haryadi Sarjono Perancangan Instrumen Penilaian Ekonomi Lingkungan Kawasan Pariwisata Alam 65 - 71 Bemard Hasibuan dan Ninin Gusdini Analisis Perilaku Konsumen Terhadap Keputusan Pembelian Voucher Kartu Prabayar Mentari Satelindo di DKI Jakarta 72 - 90 Cristhoper Rudyanto Prabowo dan Budiarto Subroto Pedoman Penulisan Naskah Jurnal I1miah Management Expose Perancangan Instrumen Penilaian Ekonomi Lingkungan Kawasan Pariwisata A1am Bemard Hasibuan, Ninin Gusdini*) Abstrak Studi ini mencobauntuk penentuan atribut yang relevan untuk memperkirakan nilai penggunaan rekreasi dan peringkat preferensi konsumen dari atribut lingkungan di daerah Puncak, yang terletak di Propinsi Jawa Barat Indonesia. Kawasan Puncak merupakan tujuan wisata berbasis alam yang terkenal. Penelitian ini menggunakan metode pemodelan pilihan, menggunakan pendekatan eksperimental pilihan untuk memperkirakan enam atribut daerah itu. Atribut itu meliputi wilayah alam, keanekaragaman hayati, tempat belanja sayuran dan buah-buahan, akses jalan, atraksi budaya lokal, dan biaya masuk biaya per orang per kunjungan. Atraksi budaya lokal dianggap sebagai atribut khusus dalam penelitian ini. Kata kunci: lingkungan, penilaian ekonomi, pembangunan berkelanjutan, model pilihan, Pendahuluan di Jawa Barat. -

An Obsessed Mariner's Notes on the Ningpo: a Vessel from the Junk Trade

An Obsessed Mariner's Notes on the Ningpo: A Vessel from the Junk Trade Explorations in Southeast Asian Studies A Journal of the Southeast Asian Studies Student Association Vol 1, No. 2 Fall 1997 Contents Article 1 Article 2 Article 3 Article 4 Article 5 Article 6 Article 7 Article 8 An Obsessed Mariner's Notes on the Ningpo A Vessel from the Junk Trade Hans Van Tilburg Hans Van Tilberg is a Ph.D. candidate in History and instructor of the maritime archaeology field school at the University of Hawai'i, Manoa. His research interests have focused on maritime history and underwater archaeology in Asia, Southeast Asia, and the Pacific. Notes The topic of Chinese shipping to and from Southeast Asia has fascinated me for quite a while now. One of the reasons I find it so interesting is that it's such a difficult subject to research. One of the main problems seems to be that many aspects of the private commercial sea-going trade simply went unrecorded. Often only the barest information of "size of ship" and "number of crew" was ever committed to register, while the efforts of ship construction, fitting out, manning, and the details of the actual voyages, remained known only at the village or family level. And as has been noted by many observers, officially the Chinese government had very little interest in the activities of those Chinese who went abroad, those who were foolish enough to want to travel so many miles away from home. Yet the influence of what is commonly known as the Junk Trade, especially in the eighteeth and nineteenth centuries, is no small subject. -

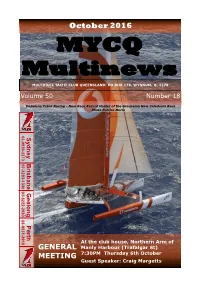

October 2016

October 2016 MULTIHULL YACHT CLUB QUEENSLAND: PO BOX 178, WYNNUM. Q. 4178 Volume 50 Number 18 Vodafone Frank Racing - New Race Record Holder of the Groupama New Caledonia Race Photo Patrice Morin 02 Sydney Brisbane Geelong Perth Geelong Brisbane Sydney - 9939 - 2273 07 2273 - 3203 - 1330 03 - 5222 - 2930 082930 - 9331 - 3910 3910 At the club house, Northern Arm of GENERAL Manly Harbour (Trafalgar St) MEETING 7:30PM Thursday 6th October Guest Speaker: Craig Margetts 2 Monthly Events 8-9th October St Helena Cup 15-16th October Spring Series Passage Series Combined Clubs Races 13 & 14 23rd October Triangles 29th-30th October Mooloolaba Weekend Commodore’s Comment By Bruce Wieland SPRING SERIES The new MYCQ Spring Series kicks off this coming weekend. The first leg is the St Helena Cup, followed by two very innovative courses the following weekend featuring optional simultaneous starts at either north or south of the river. The northern and southern courses overlap so both fleets will cross paths several times. The concept of these courses is the brainchild of Past Commodore Richard Jenkins and promises to be a lot of fun. The final weekend of the Spring Series will include the MCC triangles on Sunday the 23rd October. For the cruisers, THERE ARE SHORTENED COURSES, so find a crew and come sailing with the race fleet! OMR VIDEO The edited video of the OMR Review Committee information meeting is finally completed and is now available on the MYCQ website. Thanks to Sean for capturing the essence of the meeting, but a big thanks also to the OMR Committee members Alasdair Noble, Mike Hodges and Geoff Cruse for their easily understood presentation detailing the amendments to the OMR Rule. -

The Making of Middle Indonesia Verhandelingen Van Het Koninklijk Instituut Voor Taal-, Land- En Volkenkunde

The Making of Middle Indonesia Verhandelingen van het Koninklijk Instituut voor Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde Edited by Rosemarijn Hoefte KITLV, Leiden Henk Schulte Nordholt KITLV, Leiden Editorial Board Michael Laffan Princeton University Adrian Vickers Sydney University Anna Tsing University of California Santa Cruz VOLUME 293 Power and Place in Southeast Asia Edited by Gerry van Klinken (KITLV) Edward Aspinall (Australian National University) VOLUME 5 The titles published in this series are listed at brill.com/vki The Making of Middle Indonesia Middle Classes in Kupang Town, 1930s–1980s By Gerry van Klinken LEIDEN • BOSTON 2014 This is an open access title distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution‐ Noncommercial 3.0 Unported (CC‐BY‐NC 3.0) License, which permits any non‐commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited. The realization of this publication was made possible by the support of KITLV (Royal Netherlands Institute of Southeast Asian and Caribbean Studies). Cover illustration: PKI provincial Deputy Secretary Samuel Piry in Waingapu, about 1964 (photo courtesy Mr. Ratu Piry, Waingapu). Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Klinken, Geert Arend van. The Making of middle Indonesia : middle classes in Kupang town, 1930s-1980s / by Gerry van Klinken. pages cm. -- (Verhandelingen van het Koninklijk Instituut voor Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde, ISSN 1572-1892; volume 293) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-90-04-26508-0 (hardback : acid-free paper) -- ISBN 978-90-04-26542-4 (e-book) 1. Middle class--Indonesia--Kupang (Nusa Tenggara Timur) 2. City and town life--Indonesia--Kupang (Nusa Tenggara Timur) 3. -

Enhanced Perioperative Care in Liver and Pancreat Surgery

Enhanced perioperative care in liver and pancreat surgery Citation for published version (APA): Coolsen, M. M. E. (2014). Enhanced perioperative care in liver and pancreat surgery. Maastricht University. https://doi.org/10.26481/dis.20141031mc Document status and date: Published: 01/01/2014 DOI: 10.26481/dis.20141031mc Document Version: Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Please check the document version of this publication: • A submitted manuscript is the version of the article upon submission and before peer-review. There can be important differences between the submitted version and the official published version of record. People interested in the research are advised to contact the author for the final version of the publication, or visit the DOI to the publisher's website. • The final author version and the galley proof are versions of the publication after peer review. • The final published version features the final layout of the paper including the volume, issue and page numbers. Link to publication General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal. -

* Omslag Dutch Ships in Tropical:DEF 18-08-09 13:30 Pagina 1

* omslag Dutch Ships in Tropical:DEF 18-08-09 13:30 Pagina 1 dutch ships in tropical waters robert parthesius The end of the 16th century saw Dutch expansion in Asia, as the Dutch East India Company (the VOC) was fast becoming an Asian power, both political and economic. By 1669, the VOC was the richest private company the world had ever seen. This landmark study looks at perhaps the most important tool in the Company’ trading – its ships. In order to reconstruct the complete shipping activities of the VOC, the author created a unique database of the ships’ movements, including frigates and other, hitherto ignored, smaller vessels. Parthesius’s research into the routes and the types of ships in the service of the VOC proves that it was precisely the wide range of types and sizes of vessels that gave the Company the ability to sail – and continue its profitable trade – the year round. Furthermore, it appears that the VOC commanded at least twice the number of ships than earlier historians have ascertained. Combining the best of maritime and social history, this book will change our understanding of the commercial dynamics of the most successful economic organization of the period. robert parthesius Robert Parthesius is a naval historian and director of the Centre for International Heritage Activities in Leiden. dutch ships in amsterdam tropical waters studies in the dutch golden age The Development of 978 90 5356 517 9 the Dutch East India Company (voc) Amsterdam University Press Shipping Network in Asia www.aup.nl dissertation 1595-1660 Amsterdam University Press Dutch Ships in Tropical Waters Dutch Ships in Tropical Waters The development of the Dutch East India Company (VOC) shipping network in Asia - Robert Parthesius Founded in as part of the Faculty of Humanities of the University of Amsterdam (UvA), the Amsterdam Centre for the Study of the Golden Age (Amsterdams Centrum voor de Studie van de Gouden Eeuw) aims to promote the history and culture of the Dutch Republic during the ‘long’ seventeenth century (c. -

Lu Statement2 REDACTED

Alice Lu 4/8/16 ANTHRO 1218 Building a Quick, Navigable Ship to Evade Enemies in the First Opium War Previously, you followed me on a journey to identify this ship model. Now, we are going to take what we learned about its role in the First Opium War to examine specific elements of ship construction. Knowing this Chinese junk fought in the First Opium War, we can extrapolate information about where it was built, how it was constructed based on the region, and if these construction techniques were effective. Since these junks fought in the First Opium War, they must have met requirements in order to be operational in naval warfare; as seen by various elements of this model’s construction, including hull shape, navigation, and propulsion systems, this ship was built to be strong, stable, and easily maneuverable, giving it an advantage in traditional oceanic warfare. From geographic information on the First Opium War as well as the shape and elements of the hull, we can categorize this vessel as a southeastern type of Chinese junk (either a fuchuan or guanchuan), which were known for their stability in rough seas. The fuchuan and guanchuan were both named after the region where it is built, the Fujian and Guandong provinces of southeastern China (Green, 2), where much of the First Opium War was fought (Figure 1). These ships were built for speed and navigating rough waters (Qiupeng, 496). This ship model has a long gu or keel timber painted red, running along the length of the boat; it also has a V-shaped hull, which matches descriptions of both a fuchuan and a guanchuan (Ward, 29-30; Davies, 207; Chen, 1; Green, 2) (Figure 2). -

Ronan Shortpaper

A Chinese War Junk of the Opium War Era John Henry Ronan, Jr. ANTHRO 1218 Artifact number 99-12-60/52938 sits in the storage of the Peabody Museum, listed only as “War Boat”. The ship model, roughly 2 feet long and a foot and a half high, features unique and prominent sails. These sails, known as Chinese lugsails or junk rigs, have timbers called battens running across their entire width. The battens give the sails a sturdy appearance, and make the sails easy to control in changing trade winds. Wicker shields also run along the port and starboard sides of the deck and a wicker canopy covers the ship’s stern. It is interesting to note that the wicker shields coexist with a breech loading cannon on the starboard side, as well as edged weapons at stern. The wicker shields would seemingly serve little use up against a cannon, and it is hard to believe that the two can coexist on a ship of the same era. The final initial observation is the unique deep keel and rudder, both of which have diamond shaped holes all along them. Taken together, these observations point to the ship being a Chinese Junk, and the heavy armaments on board (and the artifact’s title) point to the ship being a War Junk. Digging a little deeper, we can conclude that this ship model is likely an 1840 Chinese War Junk, like those that would have been used in the First Opium War (1839-1842). In many ways this ship model is representative of China in the mid 19th century, a country mired in antiquated traditions facing a growingly belligerent and technological advanced world. -

A Description of the Chinese Junk, “Keying.”

This is a reproduction of a library book that was digitized by Google as part of an ongoing effort to preserve the information in books and make it universally accessible. https://books.google.com 0,5 ,Tl'mI‘PL‘II ; awn‘ '"HIxqmnnflm‘xvii-Quincy; w"1“mifiwugEEMmmIHWm.‘ ‘ V ‘ 77,‘; a i‘‘ 2.; i _ } V MW4'‘ ’ L "'H‘ {HM ‘, A , , ‘1 v‘ ‘ ‘3 ‘ t , ‘a i i t L‘ ‘H ‘ xx?‘ \ m : THEKEYING. .‘ / ‘1.". M wt‘ ’ \ H. 1} ' ‘ ~ . / Ah I A DESCRIPTION CHINESE JUNK, , “IKEYIENQ.” /< ii " FOURTH ED'ITION. ‘3c “WW .1» PRINTED FOR THE PROPRIETORS OF THE (.1 JUNK, AND SOLD ONLY ON BOARD. LONDON, 1848. m) M0 y' g J. SUCH, Printer, 29, Budge Row, Watling street, City. DESCRIPTION OF THE KEYING. E may venture to say, that, if any person had i been bold enough, three years since, to have ‘ predicted that we should have had, within the ‘ walls of the East India Docks, a Chinese Junk, ‘ ‘ with her crew and rigging, the predicter would ‘ have been thought a visionary. And yet here is ' one, open to our inspection, after having passed / over, in its voyage from the Celestial Empire to our own, a course equal in length to the entire circuit of the globe. Not very long since, there was exhib ited, near Hyde Park, a most interesting and valuable collection of Chinese curiosities. These, however, were things which could be put into packing cases, and transported, with comparative facility, from one part of the world to another : the difliculty of bringing them to England depended more upon the proprietors’ means than upon anything else.