Javier Fuentes-León Undertow 2009

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

DUARTE RICAURTE, FREDDY ELIAS.Pdf

Máster Creación de Guiones Audiovisuales Trabajo Fin de Máster UNIR Universidad Internacional de la Rioja Freddy Elías Duarte Ricaurte Indice 1. Ficha Técnica Págs. 3-4 2. Novedad e Interés Pág. 4 3. Motivaciones del Autor Pág. 5 4. Referentes Narrativos Págs. 5-6 5. Referentes Estilisticos Pág. 6 6. Ventajas Competitivas Pág. 7 7. Público Objetivo Pág. 7 8. Package 8.1 Equipo Artístico Págs. 7-8 8.2 Equipo Técnico Pág. 9 9. Locaciones Pág. 10 10. Box Oce Reference Pág. 11 11. Plan de Financiación Pág. 12 12. Plan de Promoción y Distribución Pág. 12-13-14 13. Cierre de venta Pág. 14 14. Anexo (Guion) Pág. 15 1. Ficha Técnica TÍTULO: “FALSOS POSITIVOS. Las dos caras de la moneda”. MAYOR GENERAL MONTOYA: AUTOR: FREDDY ELIAS DUARTE R. Militar de unos 53 años, de apariencia alta y fuerte, con rasgos marcados en su rostro y mirada fría. Es de armas tomar, con don de mando y consigue todo lo que se propone. Le gusta el dinero FORMATO: CORTOMETRAJE y por él, pasa por encima de quién se le atraviese. DURACIÓN: 23 minutos SOLDADO SOTOMAYOR: HIGH CONCEPT: Ambicioso e hipócrita que busca solo su bien y no importa traicionar a las personas que le han Hombre que se infiltra en las filas del Ejército Nacional de Colombia para buscar los culpables dado la mano. De apariencia fuerte y de unos 24 años. de la muerte de su hermano, caído en las redadas de los “Falsos Positivos” para hacerle justicia. Aunque estos personajes podrán ser interpretados por actores no muy conocidos a nivel interna- SINOPSIS: cional, el valor de producción de cada personaje a nivel de empatía con el espectador es alto, pues Ricardo Valendia es un joven trabajador de clase media, que vive en una casa humilde en el muni- estos se sentirán identificados con las personalidades y en cierta manera, las situaciones por la cipio de Soacha a las afueras de Bogotá. -

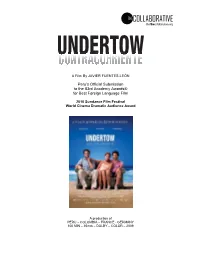

Undertow Presskit

A Film By JAVIER FUENTES-LEÓN Peru’s Official Submission to the 83rd Academy Awards® for Best Foreign Language Film 2010 Sundance Film Festival World Cinema Dramatic Audience Award A production of PERU – COLOMBIA – FRANCE - GERMANY 100 MIN – 35mm – DOLBY – COLOR – 2009 UNDERTOW (CONTRACORRIENTE) Page 2 of 19 AWARDS Sebastiane Award for Best LBGT Film — San Sebastian Int'l Film Festival 2009 Audience Award in World Dramatic Competition — Sundance 2010 Audience Award in Official Competition — Cartagena Int'l Film Festival 2010 Audience Award in Iberoamerican Competition — Miami Int'l Film Festival 2010 Audience Award in Festivalissimo — Montreal Latin American Film Festival 2010 NAHCC Award to Best Hispanic Director — Nashville Film Festival 2010 Special Award for Originality of Vision — Miami Gay and Lesbian Film Festival 2010 Audience Award — Chicago Latino Film Festival 2010 Latin Angel Audience Award — Utrecht Latin American Film Festival 2010 Latin Angel Youth Award — Utrecht Latin American Film Festival 2010 Jury Award for Best Film — Festival La Chimenea Verde 2010, Villaverde, Madrid Audience Award, Best Narrative Feature — Provincetown Int'l Film Festival 2010 Mayor of Trencin Honorary Award — Slovakia ArtFilmFest 2010 Outstanding First Feature Jury Award — Frameline34, The San Francisco LGBT International Film Festival, 2010 Audience Award for Best First Feature — Galway International Film Festival 2010, Ireland Special Programming Award for Artistic Achievement — OUTFEST 2010, Los Angeles Jury Award for Best Feature Film — Qfest -

Here the Trained to Be a Spy in the Army by Her Adop- Phone Lines Are Manned Entirely by Celebri- 4 Tive Father to Seek Revenge Against Their Ties

*LIST_619_ALT.qxp_LIS_1006_LISTINGS 6/6/19 12:32 PM Page 1 WWW.WORLDSCREENINGS.COMTVL JUNE 2019ISTINGNATPE BUDAPEST, SUNNY SIDE & ANNECYS EDITION THE LEADING SOURCE FOR PROGRAM INFORMATION TRULY GLOBAL WorldScreen.com *LIST_619_ALT.qxp_LIS_1006_LISTINGS 6/6/19 12:32 PM Page 2 2 TV LISTINGS NATPE BUDAPEST INTERNATIONAL EXHIBITOR DIRECTORY Complete listings for the companies in bold can be found in this edition of TV Listings. A+E Networks Suite 224 Kwanza MT 44 Aardman Animations Suite 245B Lagardère Studios Distribution MT 45 About Premium Content MT 40 Lionsgate Entertainment Suite 214 ABS-CBN Corporation MT 35 MADD Entertainment Suite 225 all3media international Suite 221 MarVista Entertainment VB 24 Allspark MT 51 Media Group Ukraine Suite 248B Armoza Formats MT 29 Mediaset Distribution VB 2 ATV Suite 218 Mediatoon Distribution VB 12 Autentic Distribution MT 10 MGM Television Suite 220 Banijay Rights VB 45 & 46 MISTCO Stand 4 Bavaria Media International VB 33 Mondo TV MT 24 BBC Studios Suite 209 & 210 Monster Entertainment MT 20 Berserk Media Suite 246A NBCUniversal International Distribution Duna III & IV Blue Ant Media MT 33 Newen Distribution MT 46 Boat Rocker Rights MT 39 NTV Broadcasting Company MT 38 Bonneville Distribution VB 39 Off The Fence MT 27 Breakthrough Entertainment Suite 248A One Life Studios VB 15 Broken Arrow Media MT 16 ORF-Enterprise Suite 203 CAKE Suite 244A Parade Media MT 12 Calinos Entertainment Suite 223 Paramount Pictures VB 38 & 44 Caracol Internacional Stand 6 Passion Distribution MT 50 Carsey-Werner Television -

La Narconovela

La Narconovela Narco Star System: la recurrencia en la temática del narcotráfico Sandra Lorena Rojas Jiménez 15/ 12/ 2017 Comunicación Audiovisual Ensayo Historia y tendencia Agradecimientos Agradecer a mis incondicionales padres y hermana, a mi familia en general, cuyo apoyo ha sido fundamental para esta aventura. Agradezco a mis amigos, los que ya no están y por los que siguen estando, su amistad fue el mayor tesoro que pude tener, de cada uno aprendí lo valioso del ser humano. Agradezco a los profesores de la facultad, mediante sus amables correcciones, me guiaron en éste proyecto de graduación hasta el final. Agradezco al equipo administrativo de la facultad, quienes con amabilidad y predisposición responden ante cualquier inquietud que me surgió a lo largo de éste proceso, de la misma manera agradezco por la hermosa biblioteca que posee la facultad y a sus integrantes. Por último, agradezco a mi compañero, por la comprensión, amor y apoyo que recibo día tras día. Para todos ustedes, mucho amor, ocupan un lugar importante en mi corazón. Gracias por el aprendizaje. 2 Índice Introducción 5 Capítulo 1. El mercado de la televisión 12 1.1 Marketing Televisivo 13 1.1.1 La televisión y sus franjas horarias 15 1.2 Género y formato de televisión 17 1.2.1 Formato de ficción 19 1.2.1.1 Telenovelas Latinoamericanas 20 1.2.1.2 Series 24 1.2.1.3 Sit-com 26 1.2.2 Formato de no ficción 26 Capítulo 2. Mercado de la televisión colombiana 30 2.1 Contexto social – histórico de la televisión en Colombia 30 2.1.1 Primera etapa de la televisión colombiana 33 2.1.2 Segunda etapa de la televisión colombiana 33 2.1.3 Tercera etapa de la televisión colombiana 34 2.2 Privatización de los canales. -

The Japanese Fairy Bo

TH E JAPAN ESE F A I R Y B O 0 K R e n d e r e d i n t o E n gl i s h b y YE I T HEODORA OZA KI N e w E d iti o n with a Fro nti spi e c e by T A KE SAT O C O N ST A B LE A N D C O M P A N Y LI M I T E D L O N D O N B O M B A Y S Y D N E Y E P W R K . D UT T ON A N D C O MPA N Y N E Y O L M A R I N - R A W F R D E E A N O R O C O . ’ 3 t u ate thi z fionh TO Y OU A ND T O T H E SWEET CHILD - FRIENDSHIP THA T Y OU GAV E ME I N T H E WI T H Y OU BY T H E S EA WH E N Y OU DAYS SPENT SOUTHERN , USED T O LISTEN WI T H UN FEIGNED PLEASURE T O THESE FAI RY A STORIES FROM FA R JAP AN . M Y THEY N OW REMIND Y OU OF M Y V CHANGELESS LO E AND REMEMBRANCE . Y . T . O . omo T . E P REFA C . Tm s collection of J apanese fai ry tales is the outcome of a suggestion made to me indirectly through a friend by a Mr. -

Obitel-Español-Portugués

ObservatóriO iberO-americanO da FicçãO televisiva Obitel 2020 O melOdrama em tempOs de streaming el melOdrama en tiempOs de streaming OBSERVATÓRIO IBERO-AMERICANO DA FICÇÃO TELEVISIVA OBITEL 2020 O MELODRAMA EM TEMPOS DE STREAMING EL MELODRAMA EN TIEMPOS DE STREAMING Coordenadores-gerais Maria Immacolata Vassallo de Lopes Guillermo Orozco Gómez Coordenação desta edição Gabriela Gómez Rodríguez Coordenadores nacionais Morella Alvarado, Gustavo Aprea, Fernando Aranguren, Catarina Burnay, Borys Bustamante, Giuliana Cassano, Gabriela Gómez, Mónica Kirchheimer, Charo Lacalle, Pedro Lopes, Guillermo Orozco Gómez, Ligia Prezia Lemos, Juan Piñón, Rosario Sánchez, Luisa Torrealba, Guillermo Vásquez, Maria Immacolata Vassallo de Lopes © Globo Comunicação e Participações S.A., 2020 Capa: Letícia Lampert Projeto gráfico e editoração: Niura Fernanda Souza Produção editorial: Felícia Xavier Volkweis Revisão do português: Felícia Xavier Volkweis Revisão do espanhol: Naila Freitas Revisão gráfica: Niura Fernanda Souza Editor: Luis Antônio Paim Gomes Foto de capa: Louie Psihoyos – High-definition televisions in the information era Bibliotecária responsável: Denise Mari de Andrade Souza – CRB 10/960 M528 O melodrama em tempos de streaming / organizado por Maria Immacolata Vassallo de Lopes e Guillermo Orozco Gómez. -- Porto Alegre: Sulina, 2020. 407 p.; 14x21 cm. Edição bilíngue: El melodrama en tiempos de streaming ISBN: 978-65-5759-012-6 1. Televisão – Internet. 2. Comunicação e tecnologia – Tele- visão – Ibero-Americano. 3. Programas de televisão – Distribuição – Inter- net. 4. Televisão – Ibero-América. 4. Meios de comunicação social. 5. Co- municação social. I. Título: El melodrama en tiempos de streaming. II. Lo- pes, Maria Immacolata Vassallo de. III. Gómez, Guillermo Orozco. CDU: 654.19 659.3 CDD: 301.161 791.445 Direitos desta edição adquiridos por Globo Comunicação e Participações S.A. -

Rams Charge to District Title

Mailed free to requesting homes in Douglas, Northbridge and Uxbridge Vol. II, No. 33 Complimentary to homes by request ONLINE: WWW.BLACKSTONEVALLEYTRIBUNE.COM Friday, June 13, 2014 THIS WEEK’S District reels after QUOTE Rams charge to “Be a good listen- failed override er. Your ears will district title never get you in OFFICIALS SPEAK ON ‘WORST trouble.” MEETING IN SEVEN YEARS’ BY JOY RICHARD during the most recent Frank Tyger STONEBRIDGE PRESS STAFF WRITER School Committee meet- ing on May 27, officials NORTHBRIDGE — In voted to finalize $1.1 mil- the wake of the latest lion in cuts to the dis- INSIDE School Committee meet- trict’s 2015 budget, an ing, Northbridge Public action that resulted from A2-3— LOCAL School officials reflected the failure of the town’s last week on the major override request. A4-5— OPINION cuts planned for the 2014- Spitulnik said the A7— OBITUARIES 15 school year. cuts affected 21 teach- In a recent press ing positions, all mid- A9— SENIOR SCENE release form the district, dle school after-school A11 — SPORTS Jon Gouin photos Superintendent Dr. Nancy The 2014 Central Mass. Division 3 district champion Northbridge Rams show off that Spitulnik announced that Please Read OVERRIDE, page A8 B2 — CALENDAR they are No. 1. B4— REAL ESTATE B5 — LEGALS CARROLL PITCHES SHUTOUT IN ‘From one baseball NORTHBRIDGE VICTORY LOCAL BY JON GOUIN Northbridge High base- took a 3-0 win over sev- SPORTS CORRESPONDENT ball team on Saturday, enth-seeded Hudson shrine to another’ WORCESTER — June 7, their fifth High at Tivnan Field. -

“El Cartel De Los Sapos”. Gi

REPRESENTACIONES SOCIOCULTURALES DE MASCULINIDAD HEGEMÓNICA RECREADAS EN EL SERIADO TELEVISIVO “EL CARTEL DE LOS SAPOS”. GINA MARCELA BETANCOURT MÁRQUEZ UNIVERSIDAD AUTÓNOMA DE OCCIDENTE FACULTAD DE COMUNICACIÓN SOCIAL DEPARTAMENTO DE CIENCIAS DE LA COMUNICACIÓN PROGRAMA DE COMUNICACIÓN SOCIAL Y PERIODISMO SANTIAGO DE CALI 2012 REPRESENTACIONES SOCIOCULTURALES DE MASCULINIDAD HEGEMÓNICA RECREADAS EN EL SERIADO TELEVISIVO “EL CARTEL DE LOS SAPOS”. GINA MARCELA BETANCOURT MÁRQUEZ Proyecto de grado para optar al título de Comunicador Social-Periodista Director JAIRO NORBERTO BENAVIDES Literato con Maestría en Literatura colombiana y latinoamericana UNIVERSIDAD AUTÓNOMA DE OCCIDENTE FACULTAD DE COMUNICACIÓN SOCIAL DEPARTAMENTO DE CIENCIAS DE LA COMUNICACIÓN PROGRAMA DE COMUNICACIÓN SOCIAL Y PERIODISMO SANTIAGO DE CALI 2012 Nota de aceptación: Aprobado por el Comité de grado en cumplimiento de los requisitos exigidos por la Universidad Autónoma de Occidente para optar al título de Comunicadora Social - Periodista. ORLANDO PUENTE Jurado SOLÓN CALERO Jurado Santiago de Cali, 9 / 11 / 2012 A los hombres que hicieron de la educación una opción de vida y transmitieron a sus nietos idiosincrasias de desarrollo, y a aquellos que aunque apagaron su mirada ante la carencia de oportunidades otorgaron a su familia vidas dignas. Por guardar los secretos de mí andar, por ofrecer latidos de esperanza, contribuir a mi visión profesional y otorgar a la sociedad historias de lucha y amor, les dedico mi triunfo. A la memoria de mi abuelo Daniel Antonio Márquez, símbolo de conocimiento y a mi primo César Augusto Ríos reflejo de tenacidad. AGRADECIMIENTOS A mis padres por aportar económicamente al desarrollo educativo; abuela y tíos gracias por las atenciones y desayunos en las madrugadas. -

Home News and Comment. Wing Poultry Farm, Mr Lord Has Removed Day During the Torm

The'NewtGWn Bee .. VOLUME XXXI. , NEWTOWN, CONN., FRIDAY, JANUARY 1, 1009. NUMBER 52 Nichols Stevenson. 7 school' BRIEF MENTION. r closes. The Riverside school closed Decem- It is rumored that David Armstrong ber 21, and the teucher, Mrs Ida Sher- of Bridgeport has bought or leased the a to Marlon French wood, save prize White and con- for attendance as she did not miss a Home News and Comment. Wing Poultry Farm, Mr Lord has removed day during the torm. Bertha Smith sequently, his, received a prize for deportment and household goods to.Monroe, Gertrude Washington received a prize rfh fflfop riff tft Mrs Clarence Goodyear has returned for spelling. Vt A 'A A m m i w T from a delightful visit In Philadelphia,' ra. The Christmas exercises at the !, church, last week evening, Mrs Oscar Plumb has been enter Tuesday TRINITY PARISH. 12 m., Snuday school; at 7.30 p. m St ROSE'S. EARTHQUAKE DISASTER. were well attended and much enjoyed. talning her Bister, Miss Mabel Hayes, There was a Christmas tree for the evening prayer. of Stepney. children and they received a nice sup- Saturday morning at 9 a. m an an- of Rev and Mrs Thayer Mr and Mrs Henry Reed gave a ply presents. WEDNESDAY. mass will be It is now known that 120,000 are were presented with a large picture. CHRISTMAS AT TRINITY. niversary requiem High Christmas dinner for their children and school closed the the dead the result of earthquake Bhocks. The Wednesday, Epiphany, Holy said for the repose of the soul of the grandchildren. -

Fireworks Safety

SUMMER ’18 vol. 3 Aquatics 13 Cable TV 5 CONSUMER FIREWORKS WITHIN Community Main St. 11 THE CITY OF CEDAR FALLS: Events 19 Hearst Center 15 Professional fireworks shows are an exciting experience for everyone and Historical Society 11 are the safest fireworks displays. In the last year, the City of Cedar Falls Library 16–17 decided to restrict the use of consumer fireworks within city limits. Novelty Mayor’s Corner 3 Parks 14 type fireworks are still allowed, this would include: sparklers, snakes and Project Updates 2 glow worms, party poppers, snappers, and toy smoke devices. The sale of Public Meetings 20 consumer fireworks are still allowed; however, consumer fireworks are not Public Safety 4 Rec Center 5, 12 allowed to be used within the city limits. All retail sales locations require Stormwater 7 a license from the State Fire Marshal to sell fireworks. Waste/Recycling 9 FIREWORKS SAFETY If you are in an area where fireworks are allowed, the National Council on Fireworks Safety has some tips to help you and your family stay safe to enjoy this holiday season. • Obey the laws and regulations for the use of fireworks. • Read and understand the safety labels on your fireworks before you light. • Children should only use fireworks with direct and responsible adult supervision. Children ages 5–9 have the highest risk for injuries from fireworks. • Do not drink alcohol and use fireworks! • Wear safety glasses and ear protection when shooting fireworks. • Always have a hose and a bucket of water with you. www.fireworkssafety.org/safety-tips • Dispose of fireworks in a bucket of water. -

El Cine En Español En Los Estados Unidos Roberto Fandiño Y Joaquín Badajoz

El cine en español en los Estados Unidos Roberto Fandiño y Joaquín Badajoz Siglo XX: los hispanos Roberto Fandiño Introducción Como parte de un continente en el que la mayoría de los países son de habla española, era de esperar que, apenas surgido el cine sonoro en los Estados Unidos, nuestro idioma hicie- ra sentir en él su presencia. Se empezó por frases ocasionalmente pronunciadas en el con- texto del idioma inglés cuando una situación lo requería. Hallar esos momentos obligaría a rastrear entre películas parcial o enteramente desaparecidas o conservadas en precarias condiciones; un material que corresponde al período experimental —entre 1926 y 1929—, cuando la industria, en posesión de una técnica viable y segura, decide cambiar todas las estructuras y hacer que las películas se realicen y se proyecten con un sonido sincrónico que reproduce los sonidos ambientales y, sobre todo, las voces de los artistas que nos ha- blan desde la pantalla. Sabemos que desde sus inicios, además de las frases ocasionales incluidas con un sentido realista en películas habladas en inglés, se hicieron cortos musicales en los que, por su im- portancia, no podían faltar las canciones en nuestro idioma. Poco tiempo después, por ne- cesidades primordialmente comerciales, se llegó a las películas íntegramente habladas en español. Entre las sorpresas desagradables que trajo el sonoro a la industria estadounidense se hallaba la posibilidad de perder el mercado de los países donde no se hablaba inglés, que hasta ese momento habían podido disfrutar sin barreras de un arte basado en la univer- salidad de la imagen y en unos rótulos, fáciles de traducir a otros idiomas, que especifica- ban los diálogos o aclaraban situaciones. -

El Vuelco Del Cangrejo S R L B C W N Became the Head Writer for U.S

10.XXX Latin Wave Bro. outside:10.XXX Latin Wave Bro. outside.qxp 4/9/10 3:28 PM Page 1 , g r e b n e g a W a k i n o M r o t c e r i D l a v i t s e F — . o n a c i r e m a o n i t a L e n i c l e d r o j e m o l a s o m a t i v n i s e L . n ó i c a t n e s e r p a d a c e d s é u p s e d s a t s e u p s e r y s a t n u g e r p e d s e n o i s e s s a l e t n a r u d s e t n e s e r p n á r a t s e s o l l e e d s o h c u M . s a l r a r r a n l a n a z i l i t u Screening Schedule e u q s o v i t a c o v o r p y s o c i n ú s o d o t é m s o l r o p o , r a t n o c n e g i l e e u q s a i r o t s i h s a l n e d a d i l a n i g i r o LATIN WAVE .