An Analysis of the Built Environment, Lived Experiences and Perceptions of Pikine, Senegal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Maintenance Condition Monitoring

New trend in lubricants packaging P.20 Consumer choices lubricants survey P.18 WWW.LUBESAFRICA.COM VOL.4 • JULY-SEPTEMBER 2012 NOT FOR SALE MAIN FEATURE Improving plant maintenance through condition monitoring A guide to oil analysis July-September 2012 | LUBEZINE MAGAZINE 1 PLUS: THE MARKET REPORT P.4 Inside Front Cover Full Page Ad 2 LUBEZINE MAGAZINE | July-September 2012 WWW.L UBE S A FR I C A .COM VOL 4 CONTENTS JULY—SEPTEMBER 2012 NEWS • INDUSTRY UPDATE • NEW PRODUCTS • TECHNOLOGY • COMMENTARY MAIN FEATURE 14 | OIL ANALYSIS — THE FUNDAMENTALS INSIDE REGULARS 7 | COUNTRY FEATURE 2 | Editor’s Desk Uganda lubricants market 4 | The Market Report — a brief overview Eac to remove preferential tariff treatment on MAIN FEATURE 10 | lubes produced within Lubrication and condition monitoring Eac block to improve plant availability Motorol Lubricants Open Shop 14 | MAIN FEATURE In Kenya Puma Energy plans buyout of Oil analysis — The Fundamentals KenolKobil 18 | ADVERTISER’S FEATURE Additives exempted from Consumer choices lubricants survey PVoC standards — GFK 6 | Questions from our readers 20 | PACKAGING FEATURE 28 | Last Word Engine oil performance in New trends in lubricants packaging 8 MAINTENANCE numbers 22 | TECHNOLOGY FEATURE FEATURE Oil degradation Turbochargers 26 | PROFILE and lubrication 28 10 questions for lubricants 24 professionals EQUIPMENT 27 | ADVERTISER’S FEATURE FEATURE Lubrication equipment The ultimate solution in sugar mill for a profitable and lubrication professional workshop July-September 2012 | LUBEZINE MAGAZINE 1 Turn to Turbochargers and lubrication P.8 New trend in lubricants packaging P.20 Consumer choices lubricants survey P.18 WWW.LUBESAFRICA.COM VOL.4 • JULY-SEPTEMBER 2012 NOT FOR SALE EDITOR’SDESK VOL 3 • JANUARY-MARCH 2012 MAIN FEATURE Improving plant maintenance through EDITORIAL condition monitoring A guide to oil analysis One year and July-September 2012 | LUBEZINE MAGAZINE 1 PLUS: THE MARKET REPORT P.4 still counting! Publisher: Lubes Africa Ltd elcome to volume four of Lubezine magazine. -

Road Travel Report: Senegal

ROAD TRAVEL REPORT: SENEGAL KNOW BEFORE YOU GO… Road crashes are the greatest danger to travelers in Dakar, especially at night. Traffic seems chaotic to many U.S. drivers, especially in Dakar. Driving defensively is strongly recommended. Be alert for cyclists, motorcyclists, pedestrians, livestock and animal-drawn carts in both urban and rural areas. The government is gradually upgrading existing roads and constructing new roads. Road crashes are one of the leading causes of injury and An average of 9,600 road crashes involving injury to death in Senegal. persons occur annually, almost half of which take place in urban areas. There are 42.7 fatalities per 10,000 vehicles in Senegal, compared to 1.9 in the United States and 1.4 in the United Kingdom. ROAD REALITIES DRIVER BEHAVIORS There are 15,000 km of roads in Senegal, of which 4, Drivers often drive aggressively, speed, tailgate, make 555 km are paved. About 28% of paved roads are in fair unexpected maneuvers, disregard road markings and to good condition. pass recklessly even in the face of oncoming traffic. Most roads are two-lane, narrow and lack shoulders. Many drivers do not obey road signs, traffic signals, or Paved roads linking major cities are generally in fair to other traffic rules. good condition for daytime travel. Night travel is risky Drivers commonly try to fit two or more lanes of traffic due to inadequate lighting, variable road conditions and into one lane. the many pedestrians and non-motorized vehicles sharing the roads. Drivers commonly drive on wider sidewalks. Be alert for motorcyclists and moped riders on narrow Secondary roads may be in poor condition, especially sidewalks. -

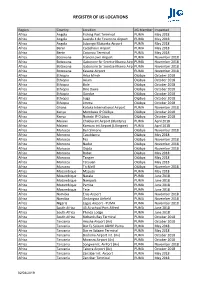

Register of IJS Locations V1.Xlsx

REGISTER OF IJS LOCATIONS Region Country Location JIG Member Inspected Africa Angola Fishing Port Terminal PUMA May 2018 Africa Angola Luanda 4 de Fevereiro Airport PUMA May 2018 Africa Angola Lubango Mukanka Airport PUMA May 2018 Africa Benin Cadjehoun Airport PUMA May 2018 Africa Benin Cotonou Terminal PUMA May 2018 Africa Botswana Francistown Airport PUMA November 2018 Africa Botswana Gaborone Sir Seretse Khama AirpoPUMA November 2018 Africa Botswana Gaborone Sir Seretse Khama AirpoPUMA November 2018 Africa Botswana Kasane Airport PUMA November 2018 Africa Ethiopia Arba Minch OiLibya October 2018 Africa Ethiopia Axum OiLibya October 2018 Africa Ethiopia Bole OiLibya October 2018 Africa Ethiopia Dire Dawa OiLibya October 2018 Africa Ethiopia Gondar OiLibya October 2018 Africa Ethiopia Jijiga OiLibya October 2018 Africa Ethiopia Jimma OiLibya October 2018 Africa Ghana Kotoka International Airport PUMA November 2018 Africa Kenya Mombasa IP OiLibya OiLibya October 2018 Africa Kenya Nairobi IP OiLibya OiLibya October 2018 Africa Malawi Chileka Int Airport (Blantyre) PUMA April 2018 Africa Malawi Kamuzu int.Airport (Lilongwe) PUMA April 2018 Africa Morocco Ben Slimane OiLibya November 2018 Africa Morocco Casablanca OiLibya May 2018 Africa Morocco Fez OiLibya November 2018 Africa Morocco Nador OiLibya November 2018 Africa Morocco Oujda OiLibya November 2018 Africa Morocco Rabat OiLibya May 2018 Africa Morocco Tangier OiLibya May 2018 Africa Morocco Tetouan OiLibya May 2018 Africa Morocco Tit Melil OiLibya November 2018 Africa Mozambique Maputo -

Senegal: Dakar-Diamniadio Highway Construction Project

AFRICAN DEVELOPMENT FUND SENEGAL: DAKAR-DIAMNIADIO HIGHWAY CONSTRUCTION PROJECT SUMMARY REPORT OF THE ENVIRONMENTAL AND SOCIAL IMPACT ASSESSMENT INFRASTRUCTURE DEPARTMENT (OINF) TRANSPORTATION UNIT (OINF.1) SEPTEMBER 2008 TABLE OF CONTENTS ABBREVIATIONS................................................................................................................................... I 1. INTRODUCTION.......................................................................................................................... 1 2. PROJECT DESCRIPTION AND JUSTIFICATION ........................................................................ 1 3. POLITICAL FRAMEWORK AND LEGAL AND ADMINISTRATIVE FRAMEWORK .................. 2 4. DESCRIPTION OF THE PROJECT ENVIRONMENT................................................................... 4 5. ALTERNATIVES TO THE PROJECT ........................................................................................... 6 6. POTENTIAL IMPACTS AND MITIGATION MEASURES ............................................................ 7 7. ENVIRONMENTAL AND SOCIAL MANAGEMENT PLAN ........................................................ 10 8. ENVIRONMENNTAL RISK MANAGEMENT ............................................................................. 12 9. MONITORING PROGRAMME .................................................................................................. 13 10. CONSULTATIONS WITH THE PUBLIC AND DISSEMINATION OF INFORMATION .............. 14 11. GENDER SITUATION ............................................................................................................... -

Cameroon's Finance Sector Goes Through Rapid Digitalization

MAJOR PROJECTS AGRICULTURE ENERGY BUSINESS IN MINING INDUSTRY SERVICES FINANCE November 2018 / N° 69 November 2018 CAMEROON Cameroon’s finance sector goes through rapid digitalization Cashew, a sector with great Oilibya rebranded, becomes potential, both for revenues Ola Energy and job creation FREE - CANNOT BE SOLD BUSINESSIN CAMEROON .COM Daily business news from Cameroon Compatible with iPads, smartphones or tablets APP AVAILABLE ON IOS AND ANDROID 3 Yasmine Bahri-Domon Cameroon goes through digital transformation Digitalization is spreading more and human resources will be necessary more to many sectors in Cameroon. to overcome issues arising from this It has become vital for any business modernization. The latter must align wishing to get closer to its customers with social fabric and structure. I and actually is the perfect tool for client believe that the transformation must retention. This is the exact case in other be gradual but also take into account African nations where digitalization direct employment, or this might lead is a boost palliating shortcomings in to an imbalance that will affect social quality of service provided. economy. Cameroon’s technology is going As said earlier, fact remains that digi- through a transformation as various talization helps financial institutions sectors indeed migrate toward digital- process their transaction and serve ization. This silent transformation is clients more rapidly. gradually taking shape and imposing There are “Made in Cameroon” apps itself to various targets. It is positive that currently let users conduct finan- evolution and it has today become a cial transactions or operations safely, must for financial institutions. It ap- using mobile devices such as phones or pears that customers have adapted to tablets. -

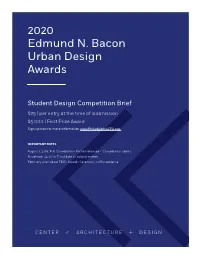

2020 Edmund N. Bacon Urban Design Awards

2020 Edmund N. Bacon Urban Design Awards Student Design Competition Brief $25 | per entry at the time of submission $5,000 | First Prize Award Sign up now for more information www.PhiladelphiaCFA.org IMPORTANT DATES August 1, 2019: Full Competition Packet released + Competition opens November 22, 2019: Final date to submit entries February 2020 (date TBD): Awards Ceremony in Philadelphia EDMUND N. BACON URBAN DESIGN AWARDS Founded in 2006 in memory of Philadelphia’s iconic 20th century city planner, Edmund N. Bacon [1910-2005], this annual program honors both professionals and students whose work epitomize excellence in urban design. Each year, a professional who has made significant contributions to the field of urban planning is selected to receive our Edmund N. Bacon Award. In addition, the winners of an international student urban design competition, envisioning a better Philadelphia, are honored with our Edmund N. Bacon Student Awards. The combined awards ceremony is hosted in Philadelphia each February. 2020 STUDENT AWARDS COMPETITION TOPIC THE BIG PICTURE: REVEALING GERMANTOWN’S ASSETS Chelten Avenue is the heart of the Germantown business district in northwest Philadelphia. The most economically diverse neighborhood in the city, Germantown is an African American community which bridges the economically disadvantaged neighborhoods of North Philadelphia to the east with the wealthier Mount Airy and Chestnut Hill neighborhoods to the west. The Chelten Avenue shopping district benefits from two regional rail stations (along different train lines) and one of the busiest bus stops in the city, located midway between the stations. In addition, the southern end of the shopping district is just steps from the expansive Wissahickon Valley Park, one of the most wild places in Philadelphia, visited by over 1 million people each year. -

Improving Urban Planning in Africa

Improving Urban Planning in Africa By: ERIC JAFFE | NOV 22, 2011 http://www.theatlanticcities.com/design/2011/11/improving-urban-planning-africa/549/ Urbanization is growing at an incredible pace in the global south, but urban planning isn't keeping up. Many planning schools in Africa still promote ideas transferred from the global north. (The master plan of Lusaka, in Zambia, for instance, was based on the concept of the garden city.) As a result, these programs often fail to prepare planners for the problems they will encounter in African cities, such as rapid growth, poverty, and informality — that is, people who pursue livelihoods outside formal employment opportunities. In 2008 the Association of African Planning Schools, a network of 43 institutions that train urban planners, began a three-year effort to reform planning education on the continent. Nancy Odendaal, project coordinator for A.A.P.S. and a planning professor at the University of Cape Town, in South Africa, offers a progress report on this effort in an upcoming issue of the journal Cities. "In order to confront the urbanisation pressures on the continent in all its unique dimensions," she writes, "fundamental shifts are needed in the materials covered in urban training programs and in the methods used to prepare practitioners." Odendaal recently answered some questions about what these shifts entail, and what they might mean for the future of Africa's cities. The aim of A.A.P.S. is to help urban planners in Africa respond to the "special circumstances" of African urbanization, according to your paper. Broadly speaking, what would those be? African urbanization does not follow the "conventional" patterns of industrialization and concomitant job creation in the North, where rapid urban growth was first experienced. -

Market-Oriented Urban Agricultural Production in Dakar

CITY CASE STUDY DAKAR MARKET-ORIENTED URBAN AGRICULTURAL PRODUCTION IN DAKAR Alain Mbaye and Paule Moustier 1. Introduction Occupying the Sahelian area of the tropical zone in a wide coastal strip (500 km along the Atlantic Ocean), Senegal covers some 196,192 km2 of gently undulating land. The climate is subtropical, with two seasons: the dry season lasting 9 months, from September to July, and the wet season from July to September. The Senegalese GNP (Gross National Product) of $570 per capita is above average for sub-Saharan Africa ($490). However, the economy is fragile and natural resources are limited. Services represent 60% of the GNP, and the rest is divided among agriculture and industry (World Bank 1996). In 1995, the total population of Senegal rose above 8,300,000 inhabitants. The urbanisation rate stands at 40%. Dakar represents half of the urban population of the region, and more than 20% of the total population. The other main cities are much smaller (Thiès: pop. 231,000; Kaolack: pop. 200000; St. Louis: pop. 160,000). Table 1: Basic facts about Senegal and Dakar Senegal Dakar (Urban Community) Area 196,192 km2 550 km2 Population (1995) 8,300,000 1,940,000 Growth rate 2,9% 4% Source: DPS 1995. The choice of Dakar as Senegal’s capital was due to its strategic location for marine shipping and its vicinity to a fertile agricultural region, the Niayes, so called for its stretches of fertile soil (Niayes), between parallel sand dunes. Since colonial times, the development of infrastructure and economic activity has been concentrated in Dakar and its surroundings. -

Dakar's Municipal Bond Issue: a Tale of Two Cities

Briefing Note 1603 May 2016 | Edward Paice Dakar’s municipal bond issue: A tale of two cities THE 19 MUNICIPALITIES OF THE CITY OF DAKAR Central and municipal governments are being overwhelmed by the rapid growth Cambérène Parcelles Assainies of Africa’s cities. Strategic planning has been insufficient and the provision of basic services to residents is worsening. Since the 1990s, widespread devolution has substantially shifted responsibility for coping with urbanisation to local Ngor Yoff Patte d’Oie authorities, yet municipal governments across Africa receive a paltry share of Grand-Yoff national income with which to discharge their responsibilities.1 Responsible and SICAP Dieuppeul-Derklé proactive city authorities are examining how to improve revenue generation and Liberté Ouakam HLM diversify their sources of finance. Municipal bonds may be a financing option for Mermoz Biscuiterie Sacré-Cœur Grand-Dakar some capital cities, depending on the legal and regulatory environment, investor appetite, and the creditworthiness of the borrower and proposed investment Fann-Point Hann-Bel-Air E-Amitié projects. This Briefing Note describes an attempt by the city of Dakar, the capital of Senegal, to launch the first municipal bond in the West African Economic and Gueule Tapée Fass-Colobane Monetary Union (WAEMU) area, and considers the ramifications of the central Médina Dakar-Plateau government blocking the initiative. Contested capital Sall also pressed for the adoption of an African Charter on Local Government and the establishment of an During the 2000s President Abdoulaye Wade sought African Union High Council on Local Authorities. For Sall, to establish Dakar as a major investment destination those closest to the people – local government – must and transform it into a “world-class” city. -

Urban Africa – Urban Africans Picture: Sandra Staudacher New Encounters of the Urban and the Rural

7th European Conference on African Studies ECAS 29 June to 1 July 2017 — University of Basel, Switzerland Urban Africa – Urban Africans Picture: Sandra Staudacher New encounters of the urban and the rural www.ecas2017.ch Convening institutions Institutional partners Funding partners ECAS7 Index 3 Welcome 4 Word from the organisers 5 Organisers 6 A* Magazine 7 Programme overview 10 Keynote speakers 12 Hesseling Prize 14 Round Tables 15 Film Sessions 20 Meetings 24 Presentations and Receptions 25 Book launches 26 Panels details (by number) 28 Detailed programme (by date) 96 List of participants 115 Publisher exhibition 130 Practical information 142 Impressum Cover picture: Street scene in Mwanza, Tanzania Picture by Sandra Staudacher. Graphic design: Strichpunkt GmbH, www.strichpunkt.ch. ___ECAS7_CofrenceBook_.indb 3 12.06.17 17:22 4 Welcome ECAS7 ia, India, South Korea, Japan, and Brazil. Currently it has 29 members, 5 associate members and 4 af- filiate members worldwide. Besides the European Conference on African Studies, by far its major ac- tivity, AEGIS promotes various activities to sup- port African Studies, such as specific training events, summer schools, and thematic conferen- ces. Another initiative, the Collaborative Research Groups (CRGs) is creating links between scholars from AEGIS and non-AEGIS centres that engage in collaborative research in new fields. AEGIS also supports the European Librarians in African Stud- ies (ELIAS). A new initiative, relating scholars in Af- rican Studies with social and economic entrepre- neurship is expressed in initiatives such as Africa Works! (African Studies Centre, Leiden) or the I have the great pleasure of welcoming to the 7th Business and Development Forum held just be- European Conference on African Studies ECAS fore ECAS. -

Application of the P-Median Problem in School Allocation

American Journal of Operations Research, 2012, 2, 253-259 http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/ajor.2012.22030 Published Online June 2012 (http://www.SciRP.org/journal/ajor) Application of the p-Median Problem in School Allocation Fagueye Ndiaye, Babacar Mbaye Ndiaye, Idrissa Ly Laboratory of Mathematics of Decision and Numerical Analysis, Cheikh Anta Diop University, Dakar, Senegal Email: [email protected], [email protected] Received April 18, 2012; revised May 20, 2012; accepted May 31, 2012 ABSTRACT This paper focus on solving the problem of optimizing students’ orientation. After four years spent in secondary school, pupils take exams and are assigned to the high school. The main difficulty of Education Department Inspection (EDI) of Dakar lies in the allocation of pupils in the suburbs. In this paper we propose an allocation model using the p-median problem. The model takes into account the distance of the standards imposed by international organizations between pupil’s home and school. The p-median problem is a location-allocation problem that takes into account the average (total) distance between demand points (pupil’s home) and facility (pupil’s school). The p-median problem is used to determine the best location to place a limited number of schools. The model has been enhanced and applied to a wide range of school location problems in suburbs. After collecting necessary numerical data to each EDI, a formulation is presented and computational results are carried out. Keywords: Non-Convex Optimization; Location Models; School Allocation 1. Introduction that has been extensively studied. The reason for the in- terest in the p-median problem is that it has practical Every year, the Education Department Inspection (EDI) applications in a wide variety of planning problems: lo- of Dakar has difficulties for assigning pupils to high schools of the suburbs. -

The Challenges of Urban Growth in West Africa: the Case of Dakar, Senegal

University of Mumbai The Challenges of Urban Growth in West Africa: The Case of Dakar, Senegal Working Paper: No. 8 Dolores Koenig Center for African Studies Area Studies Building Behind Marathi Bhasha Bhavan University of Mumbai Vidyanagari, Santacruz (E) Mumbai: 400 098. Tel Off: 022 2652 00 00 Ext. 417. E mail: [email protected] [email protected] February 2009 1 Contents Resume Introduction 3 Dakar: The Challenges of Urban Growth 5 Key Problems Facing Dakar 7 Dakar’s Environmental Challenges 8 Furnishing Housing and Essential Services 11 Planning Procedures 19 Socio-cultural Issues 24 Conclusion: Outstanding Questions 29 Bibliography 31 Figure 1: Map of Senegal 32 Figure 2: Proposed Route of the Dakar to Diamnadio Toll road 33 End Notes 33 2 Introduction Sub-Saharan Africa is becoming increasingly urbanized. If Southern African is the most urbanized region on the continent, West Africa ranks second. In 2000, 53.9% of southern Africa’s population was urban, while 39.3% of West Africans lived in urban areas. By 2030, it is estimated that Africa as a whole will be an “urban” continent, having reached the threshold of 50% urban residents. Estimates are that southern Africa will then be 68.6% urban and West Africa 57.4% urban. In contrast, East Africa will be less than 33.7% urban (UN Habitat 2007:337). Although most African cities remain small by world standards, their rates of growth are expected to be greater than areas that already include large cities. For example, the urban population of Senegal, the focus of this paper is expected grow by 2.89%/year from 2000-2010 and by 2.93% from 2010 to 2020.