Differences in an Organization's Cultural Functions Between High and Low-Performance University Soccer Teams

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Communicative Language Teaching in Korean Public Schools: an Informal Assessment

The English Connection March 2001 Volume 5 / Issue 2 A bimonthly publication of Korea Teachers of English to Speakers of Other Languages March 2001, Vol. 5, No. 2 Communicative Language Teaching in Korean Public Schools: An Informal Assessment by Dr. Samuel McGrath Introduction his article focuses on the current status of communicative language teaching in the public schools in T Korea. In order to promote communicative competence in the public schools, in 1992, the Ministry of Education mandated that English teachers use a communicative approach in class. They envisioned communi- cative language teaching (CLT) replacing the traditional audio-lingual method in middle school English teaching and the dominant grammar-translation method of high school teaching. The new approach was supposed to start in the schools in 1995. Six years have passed since the policy was adopted. However, no formal assessment by the government seems to have been done on the success or otherwise of the program. continued on page 6 Empowering Students with Learning Strategies . 9 Douglas Margolis Reading for Fluency . 11 Joshua A. Snyder SIG FAQs . 14 Calls for Papers!!! (numerous) Also in this issue KOTESOL To promote scholarship, disseminate information, and facilitate cross- cultural under standing among persons concerned with the teaching and learning of English in Korea www.kotesol.org1 The English Connection March 2001 Volume 5 / Issue 2 Language Institute of Japan Scholarship Again Available! The 2001 LIOJ Summer Workshop will be held August 5 to 10 in Odawara, Japan. The Language Institute of Japan Summer Workshops are perhaps Asia’s most recognized Language Teacher Training program. -

Seoul National University, Seoul, Korea

The Korea Association of Teachers of English 2014 International Conference Making Connections in ELT : Form, Meaning, and Functions July 4 (Friday) - July 5 (Saturday), 2014 Seoul National University, Seoul, Korea Hosted by Seoul National University Organized by The Korea Association of Teachers of English Department of English, Seoul National University Sponsored by The National Research Foundation of Korea Seoul National University Korea Institute for Curriculum and Evaluation British Council Korea Embassy of the United States International Communication Foundation CHUNGDAHM Learning English Mou Mou Hyundae Yong-O-Sa Daekyo ETS Global Neungyule Education Cambridge University Press YBM Sisa This work was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea Grant funded by the Korean Government. 2014 KATE International Conference KATE Executive Board July 2012 - June 2014 President Junil Oh (Pukyong Nationa University) Vice Presidents - Journal Editing & Publication Jeongwon Lee (Chungnam National Univ) - Planning & Coordination Hae-Dong Kim (Hankuk University of Foreign Studies) - Research & Development Yong-Yae Park (Seoul National University) - Public Relations Seongwon Lee (Gyeonsang National University) - International Affairs & Information Jeongsoon Joh (Konkuk University) Secretary Generals Hee-Kyung Lee (Yonsei University) Hyunsook Yoon (Hankuk University of Foreign Studies) Treasurer Yunkyoung Cho (Pukyong National University) International Affairs Officers Hikyoung Lee (Korea University) Isaiah WonHo Yoo (Sogang University) -

Sustainable Development and Intangible Cultural Heritage: a Youthful New Cohort in the Republic of Korea

Sustainable development and intangible cultural heritage: a youthful new cohort in the Republic of Korea Capacity-Building Workshop on ICH Safeguarding Plan for Sustainable Development, Jeonju, July 1 to 5, 2019 Perhaps the next generation of ICH enthusiasts in the Republic of Korea, this group of primary schoolchildren looked around them wide-eyed at the exhibits in the Gijisi Juldarigi museum for the tugging ritual near Dangjin city. Our workshop participants visited this unique museum during the field visit day of the training workshop. Overview Like the hero in the classical novel, 'The Tale of Yu Chungyol', who must undergo a series of tribulations and tests before his meritorious deeds are recognised and rewarded, so it seems is also the fate of ICH when it comes to sustainable development. The great tales of Korea's Joseon dynasty era are set in sweeping landscapes and encompass the range of human frailties and foibles, and our efforts are set in no less extensive a landscape, nor are they less beset by questions and interpretations both difficult and promising. The two subjects - ICH and sustainable development - were brought together firmly when the operational directives of the Unesco 2003 ICH Convention were expanded with the addition of chapter six (adopted by the Convention's General Assembly at its sixth session during May-June 1 2016). In the little over three years since, there has in the field been scant activity to connect ICH with sustainable development - or to place ICH more firmly in the set of core materials that development must employ in order to qualify as being sustainable. -

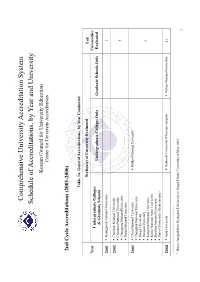

Schedule of Accreditations, by Year and University

Comprehensive University Accreditation System Schedule of Accreditations, by Year and University Korean Council for University Education Center for University Accreditation 2nd Cycle Accreditations (2001-2006) Table 1a: General Accreditations, by Year Conducted Section(s) of University Evaluated # of Year Universities Undergraduate Colleges Undergraduate Colleges Only Graduate Schools Only Evaluated & Graduate Schools 2001 Kyungpook National University 1 2002 Chonbuk National University Chonnam National University 4 Chungnam National University Pusan National University 2003 Cheju National University Mokpo National University Chungbuk National University Daegu University Daejeon University 9 Kangwon National University Korea National Sport University Sunchon National University Yonsei University (Seoul campus) 2004 Ajou University Dankook University (Cheonan campus) Mokpo National University 41 1 Name changed from Kyungsan University to Daegu Haany University in May 2003. 1 Andong National University Hanyang University (Ansan campus) Catholic University of Daegu Yonsei University (Wonju campus) Catholic University of Korea Changwon National University Chosun University Daegu Haany University1 Dankook University (Seoul campus) Dong-A University Dong-eui University Dongseo University Ewha Womans University Gyeongsang National University Hallym University Hanshin University Hansung University Hanyang University Hoseo University Inha University Inje University Jeonju University Konkuk University Korea -

KOREA at SOAS Centre of Korean Studies, SOAS Annual Review ISSUE 3: September 2009 - August 2010 SOAS

SCHOOL OF ORIENTAL AND AFRICAN STUDIES KOREA at SOAS Centre of Korean Studies, SOAS Annual Review ISSUE 3: September 2009 - August 2010 SOAS The School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS) is a college of the University of London and the only Higher Education institution in the UK specialising in the study of Asia, Africa and the Near and Middle East. SOAS is a remarkable institution. Uniquely combining language scholarship, disciplinary expertise and regional focus, it has the largest concentration in Europe of academic staff concerned with Africa, Asia and the Middle East. On the one hand, this means that SOAS remains a guardian of specialised knowledge in languages and periods and regions not available anywhere else in the UK. On the other hand, it means that SOAS scholars grapple with pressing issues - democracy, development, human rights, identity, STUDYING AT SOAS legal systems, poverty, religion, social change - confronting two-thirds of humankind. The international environment and cosmopolitan character of the School make student life a challenging, rewarding and exciting experience. We This makes SOAS synonymous with intellectual excitement and welcome students from more than 100 countries, and more than 35% of achievement. It is a global academic base and a crucial resource for them are from outside the UK. London. We live in a world of shrinking borders and of economic and technological simultaneity. Yet it is also a world in which difference The SOAS Library has more than 1.2 million items and extensive and regionalism present themselves acutely. It is a world that SOAS is electronic resources. It is the national library the study of Africa, Asia and distinctively positioned to analyse, understand and explain. -

College Codes (Outside the United States)

COLLEGE CODES (OUTSIDE THE UNITED STATES) ACT CODE COLLEGE NAME COUNTRY 7143 ARGENTINA UNIV OF MANAGEMENT ARGENTINA 7139 NATIONAL UNIVERSITY OF ENTRE RIOS ARGENTINA 6694 NATIONAL UNIVERSITY OF TUCUMAN ARGENTINA 7205 TECHNICAL INST OF BUENOS AIRES ARGENTINA 6673 UNIVERSIDAD DE BELGRANO ARGENTINA 6000 BALLARAT COLLEGE OF ADVANCED EDUCATION AUSTRALIA 7271 BOND UNIVERSITY AUSTRALIA 7122 CENTRAL QUEENSLAND UNIVERSITY AUSTRALIA 7334 CHARLES STURT UNIVERSITY AUSTRALIA 6610 CURTIN UNIVERSITY EXCHANGE PROG AUSTRALIA 6600 CURTIN UNIVERSITY OF TECHNOLOGY AUSTRALIA 7038 DEAKIN UNIVERSITY AUSTRALIA 6863 EDITH COWAN UNIVERSITY AUSTRALIA 7090 GRIFFITH UNIVERSITY AUSTRALIA 6901 LA TROBE UNIVERSITY AUSTRALIA 6001 MACQUARIE UNIVERSITY AUSTRALIA 6497 MELBOURNE COLLEGE OF ADV EDUCATION AUSTRALIA 6832 MONASH UNIVERSITY AUSTRALIA 7281 PERTH INST OF BUSINESS & TECH AUSTRALIA 6002 QUEENSLAND INSTITUTE OF TECH AUSTRALIA 6341 ROYAL MELBOURNE INST TECH EXCHANGE PROG AUSTRALIA 6537 ROYAL MELBOURNE INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY AUSTRALIA 6671 SWINBURNE INSTITUTE OF TECH AUSTRALIA 7296 THE UNIVERSITY OF MELBOURNE AUSTRALIA 7317 UNIV OF MELBOURNE EXCHANGE PROGRAM AUSTRALIA 7287 UNIV OF NEW SO WALES EXCHG PROG AUSTRALIA 6737 UNIV OF QUEENSLAND EXCHANGE PROGRAM AUSTRALIA 6756 UNIV OF SYDNEY EXCHANGE PROGRAM AUSTRALIA 7289 UNIV OF WESTERN AUSTRALIA EXCHG PRO AUSTRALIA 7332 UNIVERSITY OF ADELAIDE AUSTRALIA 7142 UNIVERSITY OF CANBERRA AUSTRALIA 7027 UNIVERSITY OF NEW SOUTH WALES AUSTRALIA 7276 UNIVERSITY OF NEWCASTLE AUSTRALIA 6331 UNIVERSITY OF QUEENSLAND AUSTRALIA 7265 UNIVERSITY -

Journal of the Korean Vacuum Society

Journal of the Korean Vacuum Society Editorial Board Information on Submission of Papers to (2013-2014) Journal of the Korean Vacuum Society Editor-in-Chief Journal of the Korean Vacuum Society, published by the Korean Vacuum Society, features up-to-date reports on significant new Kiwon Kim (Sunmoon University) findings in vacuum science and related fields. The scope of the Vice-Editor-in-Chief journal covers vacuum technology, surface and interface science, Mee-Yi Ryu (Kangwon National University) plasma and display, semiconductors and thin films, nano science and Editorial Committee technology, and energy technology. Dae Joon Kang (Sungkyunkwan University) The papers are classified into the research paper, review paper, Gi Chung Kwon (Kwangwoon University) rapid communications, and brief reports or technical notes, and the Jin Soo Kim (Chonbuk National University) Editorial Board may ask the modification and determine whether to Chang Gyoun Kim (KRICT) accept or not through the reviewing process. The review papers may be freely contributed, but may be requested to an expert of the Myungkeun Noh (LOT Vacuum Co.) relevant fields by the Editorial Board. Jae Su Yu (Kyung Hee University) Sungho Park (Sungkyunkwan University) The submission of papers may be submitted through 1. e-mail, 2. Jin Dong Song (KIST) Website, or 3. regular mail. O-Bong Yang (Chonbuk National University) 1. When submitting through the e-mail ([email protected]), please Hyo Sik Chang (Chungnam National University) specify the contact information of corresponding author (e-mail, Tel, Fax) along with the copy of paper. Yongseog Jeon (Jeonju University) 2. When using the Website, visit the Website of Korean Vacuum Woo-Seok Cheong (ETRI) Society (http://www.kvs.or.kr) and select Submission of Papers Hyun-Dam Jeong (Chonnam National University) and then Journal of the Korean Vacuum Society. -

The Jeonju-North Jeolla Chapter of KOTESOL

The Jeonju-North Jeolla Chapter of KOTESOL Generously supported by: Schedule of Events 11:30-5:30 Book Displays – 2nd Floor 11:30 Conference Doors Open - Registration 12:30-12:45 Opening Ceremony – First Floor Auditorium 12:45-1:30 Plenary Speaker: Scott Miles, Daegu-Haany University, Daegu ―Critical (but too often missing) conditions for long-term language acquisition‖ 2nd Floor 3rd Floor Rooms Sunshine E-Cinema Smile Star Sky Multimedia Publisher Sessions YL & T SIG ER SIG Info Strand 1:45-2:30 Sue Yim Sheema Doshi Jennifer Young Rocky Nelson John Wendel David Kim Session 1 Classroom Using Video Beyond the Book: Extensive Reading for Thinking Big Picture; Korea TESOL: Past, Management Effectively in the Activities for the Korean Students of an Objectives Driven Present, Future Korean Classroom Young Learner English Classroom Classroom 2:45-3:30 Hee-Jin Kim Jung-Hee Cho Aaron Jolly Young-min Park Maria Pinto Russell Bernstein Session 2 Criterion: A New Effective Ways of Setting up an Extensive Setting up Extensive Assessing Speaking What ATEK is and Technological Operating an English Reading Program for Reading at a public Skills how you can join Writing Solution Center Young Learners school: Get Your Horse Developed by ETS to Drink 3:45-4:30 James Forrest Hyunok Oh Mike Misner Scott Miles & David Van Minnen Session 3 The 'new' Use of Dialogues and Storytelling: Aaron Jolly Making the most of Cambridge Exam Role Play for Theoretical Extensive Reading and Jeonju: professionally for Teachers: The Developing Speaking Background and Assessment: -

A U Tu M N 2 0 10 the ENGLISH CONNECTION

Volume 14, Issue 3 THE ENGLISH CONNECTION A Publication of Korea Teachers of English to Speakers of Other Languages Task-Based Language Teaching: Development of Academic Proficiency By Miyuki Nakatsugawa ask-based language teaching has continued to attract interest among second language acquisition (SLA) researchers and language Tteaching professionals. However, theoretically informed principles for developing and implementing a task-based syllabus have yet to be fully established. The Cognition Hypothesis (Robinson, 2005) claims that pedagogical tasks should be designed and sequenced in order of increased cognitive complexity in order to promote language development. This article will look at Robinson ss approach to task-based syllabus design as a What’s Inside? Continued on page 8. TeachingInvited Conceptions Speakers By PAC-KOTESOLDr. Thomas S.C. 2010 Farrell English-OnlyConference ClassroomsOverview ByJulien Dr. Sang McNulty Hwang Comparing EPIK and JET National Elections 2010 By Tory S. Thorkelson ThePre-Conference Big Problem of SmallInterview: Words By JulieDr. Alan Sivula Maley Reiter NationalNegotiating Conference Identity Program PresentationKueilan ChenSchedule Email us at [email protected] at us Email Autumn 2010 Autumn To promote scholarship, disseminate information, and facilitate cross-cultural understanding among persons concerned with the teaching and learning of English in Korea. www.kotesol.org The English Connection Autumn 2010 Volume 14, Issue 3 THE ENGLISH CONNECTION A Publication of Korea Teachers of English to Speakers of Other Languages Features Cover Feature: Task-Based Language Teaching -- Development of Academic Proficiency 1 By Miyuki Nakatsugawa Contents Featurette: Using Korean Culture 11 By Kyle Devlin Featured Focus: Enhancing Vocabulary Building 12 By Dr. Sang Hwang Columns President s Message:t Roll Up Your Sleeves u 5 By Robert Capriles From the Editor ss Desk: The Spirit of Professional Development 7 By Kara MacDonald Presidential Memoirs: KOTESOL 2008-09 -- Growing and Thriving 14 By Tory S. -

ACUCA 4Th Qtr 2006

AA CC UU CC AA NN EE WW SS http://www.acuca.org ASSOCIATION OF CHRISTIAN UNIVERSITIES AND COLLEGES IN ASIA “Committed to the mission of Christian higher education of uniting all men in the community of service and fellowship.” Volume VI No. 2 Winter 2006 ACUCA MEMBER INSTITUTIONS Message from the President HONGKONG Chung Chi College, CUHK Hong Kong Baptist University s I assume the Presidency of In a world where there is a renewed Lingnan University call for character, social responsibility, INDONESIA the Association of Christian Parahyangan Catholic University Universities and Colleges in and ethical and moral norms and Petra Christian University A Satya Wacana Christian University Asia (ACUCA), I would like to begin behavior, our Christian tradition offers a Universitas Kristen Indonesia by thanking the leaders who have heritage which can help provide a moral Maranatha Christian University Duta Wacana Christian University preceded me, in particular, Dr. Janjira compass and direction. I have worked Soegijapranata Catholic University closely with many young students at the Universitas Pelita Harapan Wongkomthong, President of Christian Krida Wacana Christian University University of Thailand, my immediate Ateneo de Manila in building homes and Universitas Atma Jaya Yogyakarta JAPAN past predecessor. communities for the poor. While initially International Christian University hesitant to engage, they come out with Kwansei Gakuin University Meiji Gakuin University It was under Dr. Janjira’s leadership a new light in their face and they say, “I Nanzan University have found that my life has a purpose.” Doshisha University that ACUCA took important steps to Aoyama Gakuin University become a stronger and more relevant They find that in giving of their gifts to the St. -

Kategorisierung Der Traditionellen Koreanischen Speisen

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by OTHES 1 MASTERARBEIT Kategorisierung der traditionellen koreanischen Speisen Bakk. Marion Zimmermann Master of Arts (MA) Wien, 16. März 2010 Studienkennzahl lt. Studienblatt: 066 871 Studienrichtung lt. Studienblatt: Masterstudium Koreanologie Betreuer: Univ.-Prof. Dr. Rainer Dormels 2 INHALTSVERZEICHNIS 1. Einleitung ……………………………………………………………………….……….. S. 5 2. Forschungsstand ………………………………….....……...................... S. 7 3. Forschungsmethoden ……………………………………………………...….... .S. 14 4. Die traditionelle Esskultur Koreas …………………………………..….….. S. 21 5. Beispiele aus der traditionellen Esskultur Koreas …………….….... S. 24 5.1. Stärkendes und heilendes Essen ..……………..…………..…… S. 24 5.1.1. Allgemeines 5.1.2. Speisen 5.1.2.1. „Geröstete Bohnen”-Tag 5.1.2.2. Froscheier essen 5.1.2.3. Frühlingspflanzen und Blüten 5.1.2.3.1. Hirtentäschelkrautsuppe 5.1.2.3.2. Chrysanthemen-Salat 5.1.2.4. Beifußgerichte 5.1.2.4.1. Beifußsuppe 5.1.2.4.2. Beifußbällchen 5.1.2.4.3. Beifußreiskuchen 5.1.2.5. Kogu-Flüssigkeit trinken 5.1.2.6. Tag des sechsten Monats 5.1.2.7. Sambok 5.1.2.7.1. Samkyet„ang 5.1.2.7.2. Posint‟ang 5.1.2.7.3. Yukkyejang 5.1.2.7.4. Adzuki-Bohnenbrei 5.1.2. 8. Taro-Suppe 5.1.2. 9. Kieferpilz 5.1.2.10. Den ersten Schnee essen 5.1.2.11. Kamjettŏk 5.2. Die Speisen im Wandel der Jahreszeiten und Mondphasen ….………………………………………………….………. S. 37 5.2.1. Allgemeines 5.2.2. Speisen 5.2.2.1. Sŏllal 5.2.2.1.1. Reiskuchensuppe 5.2.2.2. -

Conference Venue

Conference Venue Address: Conference Hall (B101) in Building H14, Seoul National University 1 Gwanak-ro, Gwanak-gu, Seoul 08826, Korea For detailed information about how to get to SNU Campus, please see http://en.snu.ac.kr/campus/gwanak/address. To reach the conference venue By underground: From Exit #4 at Nakseongdae Station (Subway Line #2) → GS Petrol Station → Take #02 bus in front of Jean Boulangerie Bakery → Get off at the bus stop past SNU Dormitory → Walk down the stairs near the bus stop to reach the Building #14 By car: After entering SNU Campus via SNU rear gate, park at the parking building G12 or at the open parking area P near the Building #14. From Hoam Faculty House: Get on the #02 bus in front of SNU Faculty Apartments opposite Hoam Faculty House → Get off at the bus stop past SNU Dormitory → Walk down the stairs near the bus stop to reach the Building #14 * It takes 10-15 minutes from Hoam to Building #14 on foot. We advise you to download SNU MAP (서울대 캠퍼스 맵) from Google Play or App Store for an easier access to the conference venue. Seoul International Conference on Speech Sciences (SICSS 2019) Programme 15-16 November 2019, Seoul National University, Seoul, Korea 15 November 2019 Time Event 9:00-18:00 Registration (H14-B101) Paper Presentation 1 Session 1 Session 2 Session 3 Session 4 9:30-10:30 (H14-B101) (H14-202) (H04-302) (H03-104) Phonetics & Phonetics & Speech Disorders Speech Technology Phonology Phonology 10:30-10:40 Break 10:40-10:50 Opening Ceremony (H14-B101) Moderator: Ji-Hwan Kim (Sogang University) Keynote