Konrad Kwiet, “Rehearsing for Murder: the Beginning of the Final Solution in Lithuania in June 1941

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

On the Threshold of the Holocaust: Anti-Jewish Riots and Pogroms In

Geschichte - Erinnerung – Politik 11 11 Geschichte - Erinnerung – Politik 11 Tomasz Szarota Tomasz Szarota Tomasz Szarota Szarota Tomasz On the Threshold of the Holocaust In the early months of the German occu- volume describes various characters On the Threshold pation during WWII, many of Europe’s and their stories, revealing some striking major cities witnessed anti-Jewish riots, similarities and telling differences, while anti-Semitic incidents, and even pogroms raising tantalising questions. of the Holocaust carried out by the local population. Who took part in these excesses, and what was their attitude towards the Germans? The Author Anti-Jewish Riots and Pogroms Were they guided or spontaneous? What Tomasz Szarota is Professor at the Insti- part did the Germans play in these events tute of History of the Polish Academy in Occupied Europe and how did they manipulate them for of Sciences and serves on the Advisory their own benefit? Delving into the source Board of the Museum of the Second Warsaw – Paris – The Hague – material for Warsaw, Paris, The Hague, World War in Gda´nsk. His special interest Amsterdam, Antwerp, and Kaunas, this comprises WWII, Nazi-occupied Poland, Amsterdam – Antwerp – Kaunas study is the first to take a comparative the resistance movement, and life in look at these questions. Looking closely Warsaw and other European cities under at events many would like to forget, the the German occupation. On the the Threshold of Holocaust ISBN 978-3-631-64048-7 GEP 11_264048_Szarota_AK_A5HC PLE edition new.indd 1 31.08.15 10:52 Geschichte - Erinnerung – Politik 11 11 Geschichte - Erinnerung – Politik 11 Tomasz Szarota Tomasz Szarota Tomasz Szarota Szarota Tomasz On the Threshold of the Holocaust In the early months of the German occu- volume describes various characters On the Threshold pation during WWII, many of Europe’s and their stories, revealing some striking major cities witnessed anti-Jewish riots, similarities and telling differences, while anti-Semitic incidents, and even pogroms raising tantalising questions. -

Guides to German Records Microfilmed at Alexandria, Va

GUIDES TO GERMAN RECORDS MICROFILMED AT ALEXANDRIA, VA. No. 32. Records of the Reich Leader of the SS and Chief of the German Police (Part I) The National Archives National Archives and Records Service General Services Administration Washington: 1961 This finding aid has been prepared by the National Archives as part of its program of facilitating the use of records in its custody. The microfilm described in this guide may be consulted at the National Archives, where it is identified as RG 242, Microfilm Publication T175. To order microfilm, write to the Publications Sales Branch (NEPS), National Archives and Records Service (GSA), Washington, DC 20408. Some of the papers reproduced on the microfilm referred to in this and other guides of the same series may have been of private origin. The fact of their seizure is not believed to divest their original owners of any literary property rights in them. Anyone, therefore, who publishes them in whole or in part without permission of their authors may be held liable for infringement of such literary property rights. Library of Congress Catalog Card No. 58-9982 AMERICA! HISTORICAL ASSOCIATION COMMITTEE fOR THE STUDY OP WAR DOCUMENTS GUIDES TO GERMAN RECOBDS MICROFILMED AT ALEXAM)RIA, VA. No* 32» Records of the Reich Leader of the SS aad Chief of the German Police (HeiehsMhrer SS und Chef der Deutschen Polizei) 1) THE AMERICAN HISTORICAL ASSOCIATION (AHA) COMMITTEE FOR THE STUDY OF WAE DOCUMENTS GUIDES TO GERMAN RECORDS MICROFILMED AT ALEXANDRIA, VA* This is part of a series of Guides prepared -

Kungl Örlogsmanna Sällskapet

KUNGL ÖRLOGSMANNA SÄLLSKAPET N:r 1 1973 TIDSKRIFT I SJÖVÅSENDET FöRSTA UTGIVNINGSAR 1836 KUNGL öRLOGSMANNASÄLLSKAPET KARLSKRONA POSTGIRO 12517-3 Huvud-Redaktör och ansvarig utgivare: överstelöjtnant J. O L SEN, 371 00 Karlskrona, telefon 0455/122 50. Redaktör: Kommendörkapten B. O D I N, Rigagatan 6, 115 27 Stockholm ö, telefon 08/60 32 25. Annonsombud: Redaktör R. B L O M, Fack 126 06 Hägersten 6, telefon 08/97 68 84. Tidskrift i Sjöväsendet utkommer med ett häfte i månaden. Prenumerations pris fr. o. m. 1.1.1968 25 kronor per år, i utlandet 30 kronor. Prenumeration sker enklast genom att avgiften insättes på postgirokonto 125 17-3. Inbetalningskort utsändes med januarihäftet. Förfrågningar angående kostnader m m för annonsering ställas direkt till huvudredaktören. Införda artiklar, recensioner o dyl honoreras med 12-25 kronor per sida. För införd artikel, som av KöS anses särskilt förtjänt kan författare belönas med sällskapets medalj och/eller prispenning. Bestämmelser för Kungl. örlogsmannasällskapets tävlingsskrifter återfinnas årligen i alla häften med udda månadsn:r. TIDSKRIFT SJOVÄSENDET 136 årgången 1 och 2 häftet INNEHÅLL Sid Meddelande från Kungl. Örlogsmannasällskapet nr 6/1972 l Meddelande från Kungl. örlogsmannasällskapet nr 7/1972 3 Tyskt-italienskt gästspel på Ladoga 1942 5 Av civilekonom P. O. EKMAN Projektering av övervattensfartyg ................................... 47 Av marindirektör P. G. BöLIN "Den ryska klockan" ............................................. 69 Av professor JACOB SUNDBERG Marin eldledning S ~~gkraft e n h ~s v~~ · a . rnarinn e nhe ter beror i e ldl edningssyste~1 utvecklats. som visa i sig nå goda totalprestanda o-.: h hög funktions- Notiser från när och fjärran 97 bog grad på effektiviteten hos deras vapen- k?nkurr.e nskrafuga även utomlands. -

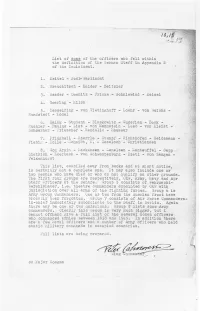

List of Some of the Officers ~~10 Fall Within the Definition of the German

-------;-:-~---,-..;-..............- ........- List of s ome of t he officers ~~10 fall within t he de finition of t he German St af f . in Appendix B· of t he I n cii c tment . 1 . Kei t e l - J odl- Aar l imont 2 . Br auchi t s ch - Halder - Zei t zl er 3. riaeder - Doeni t z - Fr i cke - Schni ewi nd - Mei s el 4. Goer i ng - fu i l ch 5. Kes s el r i ng ~ von Vi et i nghof f - Loehr - von ~e i c h s rtun c1 s t ec t ,.. l.io d eL 6. Bal ck - St ude nt - Bl a skowi t z - Gud er i an - Bock Kuchl er - Pa ul us - Li s t - von Manns t ei n - Leeb - von Kl e i ~ t Schoer ner - Fr i es sner - Rendul i c - Haus s er 7. Pf l ug bei l - Sper r l e - St umpf - Ri cht hof en - Sei a emann Fi ebi £; - Eol l e - f)chmi dt , E .- Des s l och - .Christiansen 8 . Von Arni m - Le ck e ris en - :"emelsen - l.~ a n t e u f f e l - Se pp . J i et i i ch - 1 ber ba ch - von Schweppenburg - Di e t l - von Zang en t'al kenhol's t rr hi s' list , c ompiled a way f r om books and a t. shor t notice, is c ertai nly not a complete one . It may also include one or t .wo neop .le who have ai ed or who do not q ual ify on other gr ounds . -

State of Florida Resource Manual on Holocaust Education Grades

State of Florida Resource Manual on Holocaust Education Grades 7-8 A Study in Character Education A project of the Commissioner’s Task Force on Holocaust Education Authorization for reproduction is hereby granted to the state system of public education. No authorization is granted for distribution or reproduction outside the state system of public education without prior approval in writing. The views of this document do not necessarily represent those of the Florida Department of Education. 2 Table of Contents Introduction Definition of the Term Holocaust ............................................................ 7 Why Teach about the Holocaust............................................................. 8 The Question of Rationale.............................................................. 8 Florida’s Legislature/DOE Required Instruction.............................. 9 Required Instruction 1003.42, F.S.................................................. 9 Developing a Holocaust Unit .................................................................. 9 Interdisciplinary and Integrated Units ..................................................... 11 Suggested Topic Areas for a Course of Study on the Holocaust............ 11 Suggested Learning Activities ................................................................ 12 Eyewitnesses in Your Classroom ........................................................... 12 Discussion Points/Questions for Survivors ............................................. 13 Commonly Asked Questions by Students -

Hitler's Green Army: the German Order Police and Their European Auxiliaries, 1933-1945 Volume II Eastern Europe and the Balkans by Antonio J

Hitler's Green Army: The German Order Police and their European Auxiliaries, 1933-1945 Volume II Eastern Europe and the Balkans By Antonio J. Munoz Color Plates by Darko Pavlovic Above: the Band and Standard of the German Police in 1938. Table of Contents Acknowledgements 5 Foreword 7 Introduction to the Balkans Section 9 Chapter 1 - 19 Poland 19 The Growth of the German Police 19 The SS and the Order Police Invade Poland 20 Notes on the Einsatzgruppen Officers 23 Additional SS and Police Units 30 The Mission Assigned to the SS and Police Forces in Poland 30 Chapter 2 - 43 Garrisoning Poland 43 German Order Police Battalions in Poland, 1939-1945 53 The German Kolonialpolizei 60 Auxiliary Police Forces in Poland 65 The Polish Blue Police 65 The Ethnic-German Selbstschutz and Sonderdienst in Poland 67 The Ukrainian Schutzmannschaft and Galician Police 67 The Jewish Order Police 69 Polish Guerrilla Forces and Regions 71 Collaboration of the Police in the Extermination of the Polish Jews 74 Garrisoning Poland: The 72nd Police Battalion - a Typical Occupation Unit 80 Garrisoning Poland: The Realities of the German Occupation 81 Chapter 3- 87 Complicity in the Atrocities by the German Order Police Forces in Poland 87 The Partisan War Escalates in Poland 97 The Polish Partisan Army 101 Jewish Bolshevism? 102 The Ukrainian Nationalist Guerrillas 103 The War Against the Polish Partisans in 1943 104 The War Against the Jews in 1943: The Warsaw Ghetto No Longer Exists! 109 Revolt in the Bialystok Ghetto Ill Revolt in the Sobibor Death Camp 112 TheLuftschutspolizei andFliegergruppez.b.V. -

Introduction

Notes Introduction 1This study uses ‘Estonian Veterans’ League’ as the most practical translation of the Eesti Vabadussõjalaste Liit (‘Veterans’ League of the Estonian War of Independence’). The popular term for a Veterans’ League member was vaps (plural: vapsid), or vabs, derived from vabadussõjalane (‘War of Independence veteran’). This often appears mistakenly capitalized as VAPS. A term for the Veterans frequently found in historical literature is ‘Freedom Fighters’, the direct translation of the German Freiheitskämpfer. Another unsatisfactory translation which appears in older literature is ‘Liberators’. It should be noted that until 11 August 1933 the organization was formally called Eesti Vabadussõjalaste Keskliit (‘The Estonian War of Independence Veterans’ Central League’). 2 Ernst Nolte, The Three Faces of Fascism (London, 1965), p. 12. 3 Eduard Laaman, Vabadussõjalased diktatuuri teel (Tallinn, 1933); Erakonnad Eestis (Tartu, 1934), pp. 54–62; ‘Põhiseaduse kriisi arenemine 1928–1933’, in Põhiseadus ja Rahvuskogu (Tallinn, 1937), pp. 29–45; Konstantin Päts. Poliitika- ja riigimees (Stockholm, 1949). 4 Märt Raud, Kaks suurt: Jaan Tõnisson, Konstantin Päts ja nende ajastu (Toronto, 1953); Evald Uustalu, The History of Estonian People (London, 1952); Artur Mägi, Das Staatsleben Estlands während seiner Selbständigkeit. I. Das Regierungssystem (Stockholm, 1967). 5 William Tomingas, Vaikiv ajastu Eestis (New York, 1961). 6 Georg von Rauch, The Baltic States: The Years of Independence 1917–1940 (London, 1974); V. Stanley Vardys, ‘The Rise of Authoritarianism in the Baltic States’, in V. Stanley Vardys and Romuald J. Misiunas, eds., The Baltic States in War and Peace (University Park, Pennsylvania, 1978), pp. 65–80; Toivo U. Raun, Estonia and the Estonians (Stanford, 1991); John Hiden and Patrick Salmon, The Baltic Nations and Europe: Estonia, Latvia & Lithuania in the Twentieth Century (London, 1991). -

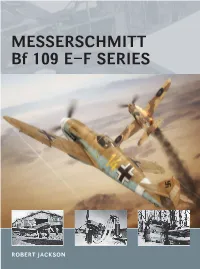

Messerschmitt Bf 109 E–F Series

MESSERSCHMITT Bf 109 E–F SERIES ROBERT JACKSON 19/06/2015 12:23 Key MESSERSCHMITT Bf 109E-3 1. Three-blade VDM variable pitch propeller G 2. Daimler-Benz DB 601 engine, 12-cylinder inverted-Vee, 1,150hp 3. Exhaust 4. Engine mounting frame 5. Outwards-retracting main undercarriage ABOUT THE AUTHOR AND ILLUSTRATOR 6. Two 20mm cannon, one in each wing 7. Automatic leading edge slats ROBERT JACKSON is a full-time writer and lecturer, mainly on 8. Wing structure: All metal, single main spar, stressed skin covering aerospace and defense issues, and was the defense correspondent 9. Split flaps for North of England Newspapers. He is the author of more than 10. All-metal strut-braced tail unit 60 books on aviation and military subjects, including operational 11. All-metal monocoque fuselage histories on famous aircraft such as the Mustang, Spitfire and 12. Radio mast Canberra. A former pilot and navigation instructor, he was a 13. 8mm pilot armour plating squadron leader in the RAF Volunteer Reserve. 14. Cockpit canopy hinged to open to starboard 11 15. Staggered pair of 7.92mm MG17 machine guns firing through 12 propeller ADAM TOOBY is an internationally renowned digital aviation artist and illustrator. His work can be found in publications worldwide and as box art for model aircraft kits. He also runs a successful 14 13 illustration studio and aviation prints business 15 10 1 9 8 4 2 3 6 7 5 AVG_23 Inner.v2.indd 1 22/06/2015 09:47 AIR VANGUARD 23 MESSERSCHMITT Bf 109 E–F SERIES ROBERT JACKSON AVG_23_Messerschmitt_Bf_109.layout.v11.indd 1 23/06/2015 09:54 This electronic edition published 2015 by Bloomsbury Publishing Plc First published in Great Britain in 2015 by Osprey Publishing, PO Box 883, Oxford, OX1 9PL, UK PO Box 3985, New York, NY 10185-3985, USA E-mail: [email protected] Osprey Publishing, part of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc © 2015 Osprey Publishing Ltd. -

Holocaust and Genocide 16:1

“Anticipatory Obedience” and the Nazi Implementation of the Holocaust in the Ukraine: A Case Study of Central and Peripheral Forces in the Generalbezirk Zhytomyr, 1941–1944 Wendy Lower Center for Advanced Holocaust Studies United States Holocaust Memorial Museum Numerous recent studies of the Holocaust as it occurred in the occupied So- viet territories have shifted attention from the central German leadership to the role of regional officials and administrators. The following case study offers an example of the ways central Nazi leaders directly and indirectly shaped the Holocaust at the regional level. In Zhytomyr the presence of Himmler, Hitler, and their SS-Police retinues created a unique setting in which the interaction of center and periphery can be traced. On this basis the author argues for the reconsideration of Berlin’s role in regional events generally. Since the appearance of Raul Hilberg’s path-breaking study The Destruction of the European Jews, which masterfully reconstructed the “machinery of destruction” that drove the Holocaust, historians have placed differing emphases on the role of the oper- ative functionaries and the leaders. In the past decade several young German historians (inspired by the work of Götz Aly and the sudden deluge of Nazi material from the former Soviet regional archives) have followed Hilberg’s lead by stressing both the role of district-level leaders in the “Final Solution” and the regional features of the Holo- caust itself. Indeed these scholars have impressively demonstrated the inner workings of what might be called the “regional Holocaust.” Recent Holocaust scholarship has shifted our attention away from the origins of the genocide at the level of state policy to the role of regional leaders and events on the ground in the former Soviet Union. -

Lithuania and the Jews the Holocaust Chapter

UNITED STATES HOLOCAUST MEMORIAL MUSEUM CENTER FOR ADVANCED HOLOCAUST STUDIES Lithuania and the Jews The Holocaust Chapter Symposium Presentations W A S H I N G T O N , D. C. Lithuania and the Jews The Holocaust Chapter Symposium Presentations CENTER FOR ADVANCED HOLOCAUST STUDIES UNITED STATES HOLOCAUST MEMORIAL MUSEUM 2004 The assertions, opinions, and conclusions in this occasional paper are those of the authors. They do not necessarily reflect those of the United States Holocaust Memorial Council or of the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. First printing, July 2005 Copyright © 2005 United States Holocaust Memorial Museum Contents Foreword.......................................................................................................................................... i Paul A. Shapiro and Carl J. Rheins Lithuanian Collaboration in the “Final Solution”: Motivations and Case Studies........................1 Michael MacQueen Key Aspects of German Anti-Jewish Policy...................................................................................17 Jürgen Matthäus Jewish Cultural Life in the Vilna Ghetto .......................................................................................33 David G. Roskies Appendix: Biographies of Contributors.........................................................................................45 Foreword Centuries of intellectual, religious, and cultural achievements distinguished Lithuania as a uniquely important center of traditional Jewish arts and learning. The Jewish community -

Jewish Genocide in Galicia

Jewish Genocide in Galicia Jewish Genocide in Galicia 2nd Edition With Appendix: Vernichtungslager ‘Bełżec’ Robin O’Neil Published by © Copyright Robin O’Neil 2015 JEWISH GENOCIDE IN GALICIA All rights reserved. The right of Robin O’Nei to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, nor translated into a machine language, without the written permission of the publisher. Condition of sale This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, re-sold, hired out or otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser. ISBN Frontispiece: The Rabka 4 + 1 - incorporating the original book cover of Rudolf Reder’s ‘Bełżec’, 1946. 2nd Edition Part 1 2016: The Rabka Four + 1. First published 2011 under the title ‘The Rabka Four’. Contents Academic Excellence In Murder......................................i Dedication....................................................................... ii Lives Remembered .........................................................iv Note on Language...........................................................vi The Hunting Grounds for the Rabka 4 + 1 (zbV) 1941-1944 .........................................................................x -

Perpetrators & Possibilities: Holocaust Diaries, Resistance, and the Crisis of Imagination

Georgia State University ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University History Theses Department of History 8-3-2006 Perpetrators & Possibilities: Holocaust Diaries, Resistance, and the Crisis of Imagination Eryk Emil Tahvonen Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/history_theses Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Tahvonen, Eryk Emil, "Perpetrators & Possibilities: Holocaust Diaries, Resistance, and the Crisis of Imagination." Thesis, Georgia State University, 2006. https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/history_theses/14 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of History at ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in History Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. PERPETRATORS & POSSIBILITIES: HOLOCAUST DIARIES, RESISTANCE, AND THE CRISIS OF IMAGINATION by ERYK EMIL TAHVONEN Under the Direction of Jared Poley ABSTRACT This thesis examines the way genocide leaves marks in the writings of targeted people. It posits not only that these marks exist, but also that they indicate a type of psychological resistance. By focusing on the ways Holocaust diarists depicted Nazi perpetrators, and by concentrating on the ways language was used to distance the victim from the perpetrator, it is possible to see how Jewish diarists were engaged in alternate and subtle, but nevertheless important, forms of resistance to genocide. The thesis suggest this resistance on the part of victims is similar in many ways to well-known distancing mechanisms employed by perpetrators and that this evidence points to a “crisis of imagination” – for victims and perpetrators alike – in which the capability to envision negation and death, and to identify with the “Other” is detrimental to self-preservation.