What Has Driven Women out of Computer Science?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

John Lennon – Człowiek I Artysta Niespełniony?

Tom 12/2020, ss. 43-72 ISSN 0860-5637 e-ISSN 2657-7704 DOI: 10.19251/rtnp/2020.12(3) www.rtnp.mazowiecka.edu.pl Andrzej Dorobek Mazowiecka Uczelnia Publiczna w Płocku ORCID: 0000-0002-5102-5182 JOHN LENNON – CZŁOWIEK I ARTYSTA NIESPEŁNIONY? JOHN LENNON: A MAN AND ARTIST UNFULFIILLED? Streszczenie: Niniejszy esej jest próbą syntetycznego, poniekąd psychoanalitycznego, ujęcia biografii Johna Lennona, zarówno jako ewidentnie zagubionego geniu- sza muzyki popularnej, jak i ofiary chłopięcego kompleksu zaniedbania przez uwielbianą matkę – później wysublimowanego w kompleks kobiecej dominacji i przeniesionego na Yoko Ono, jego drugą żonę i awangardową „muzę.” W re- zultacie ich związek, w znacznym stopniu wyidealizowany przez media, został ukazany w kontekście relacji Lennona z innymi kobietami (na przykład z ciotką Mimi), sprzecznych cech jego osobowości oraz ewolucji światopoglądowej i ar- tystycznej, która doprowadziła najpierw do dramatycznego rozdarcia między popowym supergwiazdorstwem a awangardowym artystostwem, ostatecznie zaś – do faktycznej niemocy twórczej w ciągu ostatnich pięciu lat życia. Per- John Lennon – człowiek i artysta niespełniony? spektywę komparatystyczną dla tych rozważań wyznaczać będą biografie Elvisa Presleya i Micka Jaggera. Słowa kluczowe: kompleks, trauma, dominacja, „krzyk pierwotny”, gwiaz- dorstwo, artyzm, niespełnienie Summary: In this essay, the author attempts at a synthetic insight into the biography of John Lennon, both as a confused genius of popular music and a victim of the childhood complex of motherly neglect: later transformed into the one of female domination and transferred onto Yoko Ono, his second wife and avant-garde “muse.” Consequently, their marriage, largely idealized by media, is shown here in the context of Lennon’s relations with other women (mainly his mother and aunt Mimi), his contradictory psychological traits and artistic/ ideological evolution that resulted in being torn between pop superstardom, avant-garde artistry and, in last five years, virtual creative impotence. -

Comparing the Effectiveness of Mindfulness-Based Cognitive

Special Issue INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF HUMANITIES AND May 2016 CULTURAL STUDIES ISSN 2356-5926 Comparing the effectiveness of mindfulness-based cognitive therapy and treatment based on acceptance and commitment therapy on reducing anxiety and depression in women with post-traumatic stress disorder caused by the accident Najaf Abad city of Esfahan Esmaeil Mardani Zadeh MA in Clinical Psychology [email protected] Elham Yousefi MA in Clinical Psychology [email protected] Atousa Khosravi Farsani MA in Psychology Atousa [email protected] Abstract Aims Secondary trauma is a psychological consequence of direct and prolonged contact with a post-traumatic stress disorder person. The purpose of this study was to Compare the effectiveness of mindfulness-based cognitive therapy (MBCT) and treatment based on acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT) on reducing anxiety and depression in women with post-traumatic stress disorder caused by the accident, with controlling the effect of depression, anxiety and stress. Methods: In this quasi-experimental research with pretest-posttest with control group design, 36 women of post-traumatic stress disorder caused by the accident referred to Modarress Psychiatric Hospital of Esfahan, Iran in 2015 were studied. The people who have attained high score on the secondary trauma test were randomly assigned to two experimental groups and one control group. The research instruments were a demographic questionnaire, questionnaire of secondary post-traumatic stress, and questionnaire of depression, anxiety and stress. The interventions (Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy and acceptance commitment therapy) in the experimental group were 8 weeks and once a week, the control group did not receive any training. -

Features of the Application of Art-Therapeutic and Gaming Technology Based on Folk Music in Rehabilitation and Socialization of Children with Health Limitations

Scientific Foundation SPIROSKI, Skopje, Republic of Macedonia Open Access Macedonian Journal of Medical Sciences. 2020 Aug 15; 8(E):373-381. https://doi.org/10.3889/oamjms.2020.3588 eISSN: 1857-9655 Category: E - Public Health Section: Public Health Education and Training Features of the application of art-therapeutic and gaming technology based on folk music in rehabilitation and socialization of children with health limitations Natalia Ivanovna Anufrieva*, Aleksandr Vlavlenovich Kamenets, Marina Viktorovna Pereverzeva, Marina Gennadievna Kruglova Department of Sociology and Philosophy of Art, Russian State Social University, Wilhelm Pieck Street, 4/1, Moscow 129226, Russia Abstract Edited by: Ksenija Bogoeva-Kostovska AIM: The purpose of the work is to study the specifics and evaluate the effectiveness of the use of art-therapeutic Citation: Anufrieva NI, Kamenets AV, Pereverzeva MV, Kruglova MG. Features of the application of art- and gaming technologies based on musical folklore in the course of rehabilitation of children with health limitations. therapeutic and gaming technology based on folk music in rehabilitation and socialization of children with health MATERIALS AND METHODS: The socialization of such children depends largely on the characteristics of health, limitations. Open Access Maced J Med Sci. 2020 Aug 15; the principles of their training, and the effectiveness of the chosen methods. This justifies the need to analyze the 8(E):373-381. https://doi.org/10.3889/oamjms.2020.3588 *Correspondence: Natalia Ivanovna Anufrieva. practical experience and evaluate the results of efforts of specialists who deal with special children. Department of Sociology and Philosophy of Art, Russian State Social University, Wilhelm Pieck Street, 4/1, Moscow RESULTS: The results of the conducted psychological and pedagogical experiment on the use of art-therapeutic and 129226, Russia. -

Psichologijos Žodynas Dictionary of Psychology

ANGLŲ–LIETUVIŲ KALBŲ PSICHOLOGIJOS ŽODYNAS ENGLISH–LITHUANIAN DICTIONARY OF PSYCHOLOGY VILNIAUS UNIVERSITETAS Albinas Bagdonas Eglė Rimkutė ANGLŲ–LIETUVIŲ KALBŲ PSICHOLOGIJOS ŽODYNAS Apie 17 000 žodžių ENGLISH–LITHUANIAN DICTIONARY OF PSYCHOLOGY About 17 000 words VILNIAUS UNIVERSITETO LEIDYKLA VILNIUS 2013 UDK 159.9(038) Ba-119 Apsvarstė ir rekomendavo išleisti Vilniaus universiteto Filosofijos fakulteto taryba (2013 m. kovo 6 d.; protokolas Nr. 2) RECENZENTAI: prof. Audronė LINIAUSKAITĖ Klaipėdos universitetas doc. Dalia NASVYTIENĖ Lietuvos edukologijos universitetas TERMINOLOGIJOS KONSULTANTĖ dr. Palmira ZEMLEVIČIŪTĖ REDAKCINĖ KOMISIJA: Albinas BAGDONAS Vida JAKUTIENĖ Birutė POCIŪTĖ Gintautas VALICKAS Žodynas parengtas įgyvendinant Europos socialinio fondo remiamą projektą „Pripažįstamos kvalifikacijos neturinčių psichologų tikslinis perkvalifikavimas pagal Vilniaus universiteto bakalauro ir magistro studijų programas – VUPSIS“ (2011 m. rugsėjo 29 d. sutartis Nr. VP1-2.3.- ŠMM-04-V-02-001/Pars-13700-2068). Pirminis žodyno variantas (1999–2010 m.) rengtas Vilniaus universiteto Specialiosios psichologijos laboratorijos lėšomis. ISBN 978-609-459-226-3 © Albinas Bagdonas, 2013 © Eglė Rimkutė, 2013 © VU Specialiosios psichologijos laboratorija, 2013 © Vilniaus universitetas, 2013 PRATARMĖ Sparčiai plėtojantis globalizacijos proce- atvejus, kai jų vertimas į lietuvių kalbą gali sams, informacinėms technologijoms, ne- kelti sunkumų), tik tam tikroms socialinėms išvengiamai didėja ir anglų kalbos, kaip ir etninėms grupėms būdingų žodžių, slengo, -

Social Consciousness, Metaphysical Contents and Aesthetics in Select Anglophone African Factions

SOCIAL CONSCIOUSNESS, METAPHYSICAL CONTENTS AND AESTHETICS IN SELECT ANGLOPHONE AFRICAN FACTIONS By Abidemi Olufemi ADEBAYO (Matric No.104957) A Thesis in the Department of English, Submitted to the Faculty of Arts in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY of the UNIVERSITY OF IBADAN SEPTEMBER, 2014 CERTIFICATION I certify that this research was carried out by Abidemi Olufemi ADEBAYO in the Department of English, University of Ibadan, under my supervision. Professor Nelson O. Fashina Date Department of English University of Ibadan ii DEDICATION To all men of goodwill in Africa. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I acknowledge God for the gift of life. I thank my supervisor, Professor Nelson Fashina, for the sound tutelage I received from him all through the different stages of my academic career in the Department of English, University of Ibadan. He sowed the seed of thorough academic scholarship in me in my undergraduate days, nurtured it during my Master‘s degree programme and fortified same in the supervision of this research. I thank the professor profoundly. The impact of his mentoring on me is indelible. I also thank all the lecturers in the Department for constant encouragement and advice. Specific mention is made of Professor Lekan Oyeleye, Professor Remi Raji-Oyelade, Professor Tunde Omobowale, Professor Ayo Kehinde, Professor Obododinma Oha, Dr. Remy Oriaku, Dr. M. T. Lamidi, Dr. Toyin Jegede, Dr. Nike Akinjobi, Dr. Ayo Osisanwo, Dr. Ayo Ogunsiji and Dr. Adesina Sunday. I benefited from their wealth of knowledge. They guided me in the course of writing my thesis. It is important to me to appreciate the suggestion that Yinka Akintola made on how to procure books for the research. -

AVAILABLE from ABSTRACT DOCUMENT RESUME Mental

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 431 981 CG 029 333 TITLE Mental Health in Schools: New Roles for School Nurses. Addressing Barriers to Student Learning. INSTITUTION California Univ., Los Angeles. Center for Mental Health in Schools. SPONS AGENCY Health Resources and Services Administration (DHHS/PHS), Washington, DC. Maternal and Child Health Bureau. PUB DATE 1997-04-00 NOTE 298p. AVAILABLE FROM School Mental Health Project, Center for Mental Health in Schools, Dept. of Psychology, UCLA, 405 Hilgard Ave., Los Angeles, CA 90095-1563; Tel: 310-825-3634; Fax: 310-206-8716; e-mail: [email protected]; Web site: http://smhp.psych.ucla.edu (minimal fee to cover copying, postage and handling). PUB TYPE Guides Classroom Learner (051) Guides Classroom Teacher (052) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC12 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Confidentiality; Due Process; Elementary Secondary Education; *Mental Health; Prevention; *Professional Development; *School Nurses; *Staff Role; Student Development IDENTIFIERS Consent; Screening Programs ABSTRACT This set of three continuing education units is designed to be used as a professional development tool for school nurses. Each unit consists of several sections designed to stand alone. Thus, the total set can be used and taught in a straightforward sequence, or one or more units and sections can be combined into a personalized course. Each section begins with specific objectives and focusing questions to guide reading and review. Interspersed throughout each section is boxed information designed to help the learner think in greater depth about the material. Test questions are provided at the end of each section as an additional study aid. Unit 1, "Placing Mental Health into the Context of Schools and the 21st Century," provides an overview and discusses enhancing health development; addressing barriers to learning; moving toward a comprehensive approach; and responding to students' problems. -

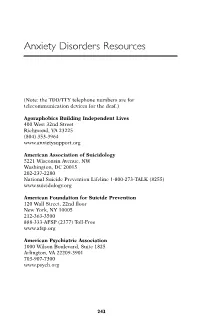

Anxiety Disorders Resources

Anxiety Disorders Resources (Note: the TDD/TTY telephone numbers are for telecommunication devices for the deaf.) Agoraphobics Building Independent Lives 400 West 32nd Street Richmond, VA 23225 (804) 353-3964 www.anxietysupport.org American Association of Suicidology 5221 Wisconsin Avenue, NW Washington, DC 20015 202-237-2280 National Suicide Prevention Lifeline 1-800-273-TALK (8255) www.suicidology.org American Foundation for Suicide Prevention 120 Wall Street, 22nd floor New York, NY 10005 212-363-3500 888-333-AFSP (2377) Toll-Free www.afsp.org American Psychiatric Association 1000 Wilson Boulevard, Suite 1825 Arlington, VA 22209-3901 703-907-7300 www.psych.org 243 244 ANXIETY DISORDERS RESOURCES American Psychological Association 750 First Street, N.E. Washington, DC 20002-4242 800-374-2721 202-336-5500 TDD/TTY: 202-336-6213 www.apa.org Anxiety Disorders Association of America 8730 Georgia Avenue, Suite 600 Silver Spring, MD 20910 240-485-1001 www.adaa.org Association for Behavioral and Cognitive Therapies 305 Seventh Avenue, 16th floor New York, NY 10001 (212) 647-1890 www.aabt.org Doctors Guide www.docguide.com Freedom from Fear 308 Seaview Avenue Staten Island, NY 10305 718-351-1717 www.freedomfromfear.org International Society for Traumatic Stress Studies 60 Revere Drive, Suite 500 Northbrook IL 60062 847-480-9028 www.istss.org MedlinePlus: Health Information www.medlineplus.gov Mental Health America (formerly National Mental Health Association) 2000 N. Beauregard St., 6t floor Alexandria, VA 22311 800-969-6MHA (6642) 703-684-7722 TTY: 800-433-5959 www.mentalhealthamerica.net ANXIETY DISORDERS RESOURCES 245 National Alliance for the Mentally Ill Colonial Place Three 2107 Wilson Boulevard, Suite 300 Arlington, VA 22201-3042 800-950-NAMI (6264) 703-524-7600 TDD: 703-516-7227 www.nami.org National Anxiety Foundation 3135 Custer Drive Lexington, KY 40517-4001 606-272-7166 National Center for Posttraumatic Stress Disorder U.S. -

Cultural Geographies

Cultural Geographies http://cgj.sagepub.com/ Ecological anxiety disorder: diagnosing the politics of the Anthropocene Paul Robbins and Sarah A. Moore Cultural Geographies 2013 20: 3 DOI: 10.1177/1474474012469887 The online version of this article can be found at: http://cgj.sagepub.com/content/20/1/3 Published by: http://www.sagepublications.com Additional services and information for Cultural Geographies can be found at: Email Alerts: http://cgj.sagepub.com/cgi/alerts Subscriptions: http://cgj.sagepub.com/subscriptions Reprints: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsReprints.nav Permissions: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav >> Version of Record - Jan 7, 2013 What is This? Downloaded from cgj.sagepub.com at UNIV OF WISCONSIN on January 14, 2013 CGJ20110.1177/1474474012469887Cultural geographiesRobbins and Moore 4698872012 Article cultural geographies 20(1) 3 –19 Ecological anxiety disorder: © The Author(s) 2012 Reprints and permission: sagepub. co.uk/journalsPermissions.nav diagnosing the politics of the DOI: 10.1177/1474474012469887 Anthropocene cgj.sagepub.com Paul Robbins University of Wisconsin-Madison, USA Sarah A. Moore University of Wisconsin-Madison, USA Abstract The quickly changing character of the global environment has predicated a number of crises in the sciences of biology and ecology. Specifically, the rapid rate of ecological change has led to the proliferation of novel ecologies. These unprecedented ecosystems and assemblages challenge the scientific, as well as cultural, core of many disciplines. This has led to divisive debates over what constitutes a ‘natural’ system state, and over what kinds of interventions, if any, should be advocated by scientists. In this paper, we review the nature of the recent discomfort, conflict, and ambivalence experienced in some sciences. -

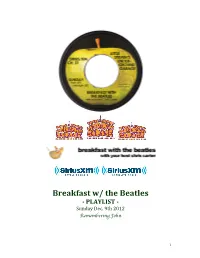

Breakfast)W/)The)Beatles) .)PLAYLIST).) Sunday'dec.'9Th'2012' Remembering John

Breakfast)w/)the)Beatles) .)PLAYLIST).) Sunday'Dec.'9th'2012' Remembering John 1 Remembering'John' John Lennon – (Just Like) Starting Over – Double Fantasy NBC NEWS BULLETIN 2 The Beatles – A Day In The Life - Sgt. Peppers Lonely Hearts Club Band Recorded Jan & Feb 1967 Quite possibly the finest Lennon/McCartney collaboration of their song-writing career. Vin Scelsa WNEW FM New York Dec.8th 1980 Paul McCartney – Here Today - Tug of War ‘82 This was Paul’s elegy for John – it was a highlight of the album, and as was the entire album, produced by George Martin. This continues to be part of Paul’s repertoire for his live shows. George Harrison – All Those Years Ago This particular track is a puzzle still somewhat unsolved. Originally written for Ringo with different lyrics, (which Ringo didn’t think was right for him), the lyrics were rewritten after John Lennon’s murder. Although Ringo did provide drums, there is a dispute as to whether Paul, Linda and Denny did backing vocals at Friar Park, or in their own studio – hence phoning it in. But Paul insists that he had asked George to play on his own track, Wanderlust, for the Tug Of War album. Having arrived at George’s Friar Park estate, they instead focused on backing vocals for All Those Years Ago. It became George’s biggest hit in 8 years, just missing the top spot on the charts. 3 2.12 BREAK/OPEN Start with songs John liked…. The Beatles – In My Life - Rubber Soul Recorded Oct.18th 1965 Of all the Lennon/McCartney collaborations only 2 songs have really been disputed by John & Paul themselves one being “Eleanor Rigby” and the other is “In My Life”. -

Bluets Press Release 030617Short

Press Release Bluets 10 March - 22 April, 2017 Opening Reception: Friday 10 March, 6 - 8 pm To benefit support.fm Annie Bielski Lucy Bull Cora Cohen Eli Farahmand Sadie Laska Sofia Leiby Rachel Eulena Williams Molly Zuckerman-Hartung Molly Zuckerman-Hartung, Small Town Mondrian, 2010. Burning in Water is pleased to present Bluets, a group exhibition of painting and sculpture organized by Sofia Leiby on view at 317 10th Avenue in New York through April 22. Eli gave me Bluets for my birthday. I related to the book as a painter who wants to think about herself as a painter without letting her personality get in the way. Maggie found a way to insert herself into blue: “I am trying to talk about what blue means, or what it means to me, apart from meaning.”1 After graduating from the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, Annie, Lucy and I started a shared document about painting and our everyday lives, and how they impacted one another. We sent photos of messes in our rooms and the insides of our purses and compared them to our paintings. We wondered how our own personalities were revealed or concealed by mark- making -- could we choose when to withhold, or expose, our relationship to our own hands and color, whether a searing red or a muted grey? It reminds me that the eye is simply a recorder, with or without our will. Perhaps the same could be said of the heart?2 Lydia Davis wrote about the Joan Mitchell’s painting Les Bluets (1973) in Artforum: Two things happened at once: the painting abruptly went beyond itself, lost its solitariness, -

Paranoid – Suspicious; Argumentative; Paranoid; Continually on the Lookout for Trickery and Abuse; Jealous; Tendency to Blame Others; Cold and Humorless

Personality Disturbance Gathering, nr.49 (key to possible disturbances) Every person may be used only once, except “by proxy” will overlap another person/condition, and there is one condition which will not be assigned to characters. 1. Agoraphobia – Fear of being out in the open or in public places; nervous; anxious 2. Autophobia/Monophobia – Extreme dislike or anger of oneself, or of an ethnic group from which one descends. 3. Anti-Social Personality Disorder – Failure to conform to societal norms; lack of remorse or indifferent; impulsivity or failure to plan ahead; consistent irresponsibility; deceitfulness. 4. Avoidant Personality Disorder – Socially awkward; fear of criticism, disapproval or rejection; views self as socially inept; reluctant to take personal risks or to engage in new activities because they may prove embarrassing. 5. Body Dysmorphic Disorder – A perceived defect of oneself. 6. Borderline – Very unstable relationships; erratic emotions; self-damaging behavior; impulsive; unpredictable aggressive and sexual behavior; sometimes similar to Autophobia/Monophobia; easily angered. 7. Brief Psychotic Disorder – Delusions, hallucination, disorganized speech or catatonic behavior which last between one and four weeks. 8. “…by Proxy” – Any condition where someone uses another (adult, children) to achieve their needs. 9. Cognitive Dissonance – the wrestling with opposing viewpoints in our mind, and determine which decision to make; our effort to fundamentally strive for harmony in our thinking. 10. Compulsive – Perfectionists, preoccupied with details, rules and schedules; more concerned about work than pleasure; serious and formal; cannot express tender feelings. 11. Compulsive Hoarding – Excessive acquisition of possessions, and failure to use or discard them, even if the items are worthless, hazardous or unsanitary. -

Innovators: Songwriters

NBER WORKING PAPER SERIES INNOVATORS: SONGWRITERS David Galenson Working Paper 15511 http://www.nber.org/papers/w15511 NATIONAL BUREAU OF ECONOMIC RESEARCH 1050 Massachusetts Avenue Cambridge, MA 02138 November 2009 The views expressed herein are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Bureau of Economic Research. NBER working papers are circulated for discussion and comment purposes. They have not been peer- reviewed or been subject to the review by the NBER Board of Directors that accompanies official NBER publications. © 2009 by David Galenson. All rights reserved. Short sections of text, not to exceed two paragraphs, may be quoted without explicit permission provided that full credit, including © notice, is given to the source. Innovators: Songwriters David Galenson NBER Working Paper No. 15511 November 2009 JEL No. N00 ABSTRACT Irving Berlin and Cole Porter were two of the great experimental songwriters of the Golden Era. They aimed to create songs that were clear and universal. Their ability to do this improved throughout much of their careers, as their skill in using language to create simple and poignant images improved with experience, and their greatest achievements came in their 40s and 50s. During the 1960s, Bob Dylan and the team of John Lennon and Paul McCartney created a conceptual revolution in popular music. Their goal was to express their own ideas and emotions in novel ways. Their creativity declined with age, as increasing experience produced habits of thought that destroyed their ability to formulate radical new departures from existing practices, so their most innovative contributions appeared early in their careers.