Russia's Strategy for Influence Through Public Diplomacy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Northern Flank

Click here for Full Issue of EIR Volume 14, Number 43, October 30, 1987 N orthem Flank by Goran Haglund The spy who went back into the cold incompetence and absurdity at the Justice Minister Wickbom is but one victim of the intelligence sAPO, typified by their keeping Palme warfare now raging in Sweden. on a "black list" of people who might be unreliable during a crisis. Pravda cites the now-deposed Wickbom say ing it's time to investigate the sApo. Months of intelligence warfare in guard accompanies the prisoner away When Bergling's prison guard, as Sweden have begun to take their toll fromand back to the prison, but leaves per an "agreement" with Bergling, ar of high-level govemment officials.The him unwatched during the night. rived at 12:45 p.m. on Oct. 6 to pick most prominentvictim so far is Justice Third, Bergling was given leaves him up at his wife's house, both Ber Minister Sten Wickbom, forced to re despite his known desire to escape. In gling and wife were gone, to every sign on Oct. 19. Wickbom's demise October 1985, a letter intercepted from body's alleged surprise. It then took was followed by the firing of three of Bergling revealed a plan to escape. until 10:45 a.m. before a nationwide his underlings at the Justice Depart Nonetheless, he was again granted a search warrantwas issued, perhaps 24 ment, among them the number-two leave in January 1986. His former hours after the escape. man, Harald Fiilth, and the resigna lawyer stated, "He is a very dangerous At first, the Social Democratic of tion of Director General VIf Larsson and experienced spy and has all the ficials of the Prisons Board, all cham of the Swedish Prisons Board, which time aimed at getting out one day." pions of "humanization of prison runs the nation's prisons. -

Political Opposition in Russia: a Troubled Transformation

EUROPE-ASIA STUDIES Vol. 67, No. 2, March 2015, 177–191 Political Opposition in Russia: A Troubled Transformation VLADIMIR GEL’MAN IN THE MID-2000S, THE DECLINE OF OPPOSITION POLITICS in Russia was so sharp and undisputed that the title of an article I wrote at the time, ‘Political Opposition in Russia: A Dying Species?’ (Gel’man 2005) met with little objection. At that time, the impact of the opposition was peripheral at best. The ‘party of power’, United Russia (Edinaya Rossiya— UR), dominated both nationwide (Remington 2008) and sub-national (Ross 2011) legislatures, and the few representatives of the opposition exerted almost no influence on decision making. The share of votes for the opposition parties (in far from ‘free and fair’ elections) was rather limited (Gel’man 2008; Golosov 2011). Even against the background of the rise of social movements in Russia, anti-regime political protests were only able to gather a minority of 100 or so participants, while environmental or cultural protection activists deliberately avoided any connections with the political opposition, justly considering being labelled ‘opposition’ as an obstacle to achieving positive results (Gladarev & Lonkila 2013; Clement 2013). In other words, political opposition in Russia was driven into very narrow ‘niches’ (Greene 2007), if not into ghettos, and spectators were rather gloomy about the chances of its rebirth. Ten years later, Russia’s political landscape looks rather different. Protest meetings in Moscow and other cities in 2011–2012 brought together hundreds of thousands of participants under political slogans, and the Russian opposition was able to multiply its ranks, to change its leadership, to reach a ‘negative consensus’ vis-a`-vis the status quo political regime, and to come to the front stage of Russian politics. -

Deception, Disinformation, and Strategic Communications: How One Interagency Group Made a Major Difference by Fletcher Schoen and Christopher J

STRATEGIC PERSPECTIVES 11 Deception, Disinformation, and Strategic Communications: How One Interagency Group Made a Major Difference by Fletcher Schoen and Christopher J. Lamb Center for Strategic Research Institute for National Strategic Studies National Defense University Institute for National Strategic Studies National Defense University The Institute for National Strategic Studies (INSS) is National Defense University’s (NDU’s) dedicated research arm. INSS includes the Center for Strategic Research, Center for Complex Operations, Center for the Study of Chinese Military Affairs, Center for Technology and National Security Policy, Center for Transatlantic Security Studies, and Conflict Records Research Center. The military and civilian analysts and staff who comprise INSS and its subcomponents execute their mission by conducting research and analysis, publishing, and participating in conferences, policy support, and outreach. The mission of INSS is to conduct strategic studies for the Secretary of Defense, Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, and the Unified Combatant Commands in support of the academic programs at NDU and to perform outreach to other U.S. Government agencies and the broader national security community. Cover: Kathleen Bailey presents evidence of forgeries to the press corps. Credit: The Washington Times Deception, Disinformation, and Strategic Communications: How One Interagency Group Made a Major Difference Deception, Disinformation, and Strategic Communications: How One Interagency Group Made a Major Difference By Fletcher Schoen and Christopher J. Lamb Institute for National Strategic Studies Strategic Perspectives, No. 11 Series Editor: Nicholas Rostow National Defense University Press Washington, D.C. June 2012 Opinions, conclusions, and recommendations expressed or implied within are solely those of the contributors and do not necessarily represent the views of the Defense Department or any other agency of the Federal Government. -

Dynamics of Innovation and the Balance of Power in Russia

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by LSE Research Online Gregory, Asmolov Dynamics of innovation and the balance of power in Russia Book section (Accepted version) Original citation: Originally published in: Hussain, Muzammil M. and Howard, Philip N., (eds.) State Power 2.0: Authoritarian Entrenchment and Political Engagement Worldwide. Routledge, Abingdon, Oxon, UK : Routledge, 2013, pp. 139-152. © 2013 The Author This version available at: http://eprints.lse.ac.uk/68001/ Available in LSE Research Online: October 2016 LSE has developed LSE Research Online so that users may access research output of the School. Copyright © and Moral Rights for the papers on t his site are retained by the individual authors and/or other copyright owners. Users may download and/or print one copy of any article(s) in LSE Research Online to facilitate their private study or for non-commercial research. You may not engage in further distribution of the material or use it for any profit-making activities or any commercial gain. You may freely distribute the URL (http://eprints.lse.ac.uk) of the LSE Research Online website. This document is the author’s submitted version of the book section. There may be differences between this version and the published version. You are advised to consult the publisher’s version if you wish to cite from it. Dynamics of Innovation and the Balance of Power in Russia Gregory Asmolov, London School of Economics and Political Science Suggested citation: Asmolov, G. (2013). “Dynamics of Innovation and the Balance of Power in Russia.” In Hussain, M. -

Public Diplomacy and Nation Branding: Conceptual Similarities and Differences

DISCUSSION PAPERS IN DIPLOMACY Public Diplomacy and Nation Branding: Conceptual Similarities and Differences Gyorgy Szondi Netherlands Institute of International Relations ‘Clingendael’ ISSN 1569-2981 DISCUSSION PAPERS IN DIPLOMACY Editors: Virginie Duthoit & Ellen Huijgh, Netherlands Institute of International Relations ‘Clingendael’ Managing Editor: Jan Melissen, Netherlands Institute of International Relations ‘Clingendael’ and Antwerp University Desk top publishing: Desiree Davidse Editorial Board Geoff Berridge, University of Leicester Rik Coolsaet, University of Ghent Erik Goldstein, Boston University Alan Henrikson, Tufts University Donna Lee, Birmingham University Spencer Mawby, University of Nottingham Paul Sharp, University of Minnesota Duluth Copyright Notice © Gyorgy Szondi, October 2008 All rights reserved. No reproduction, copy, or transmission of this publication, or part thereof in excess of one paragraph (other than as a PDF file at the discretion of the Netherlands Institute of International Relations ‘Clingendael’) may be made without the written permission of the author. ABSTRACT The aim of this study is to explore potential relationships between public diplomacy and nation branding, two emerging fields of studies, which are increasingly being used in the same context. After examining the origins of the two concepts, a review of definitions and conceptualisations provide a point of departure for exploring the relationship between the two areas. Depending on the degree of integration, five conceptual models are outlined, each with potential pitfalls as well as advantages. According to the first approach, public diplomacy and nation branding are unrelated and do not share any common grounds. In other views, however, these concepts are related and it is possible to identify different degrees of integration between public diplomacy and nation branding. -

The Annexation of Crimea

IB GLOBAL POLITICS THE ANNEXATION OF CRIMEA CASE STUDY UWC COSTA RICA WWW.GLOPOIB.WORDPRESS.COM WWW.GLOPOIB.WORDPRESS.COM 1 MAP Map taken from the Economist website at https://www.economist.com/europe/2019/06/08/crimea-is-still-in- limbo-five-years-after-russia-seized-it WWW.GLOPOIB.WORDPRESS.COM 2 INTRODUCTION Ukraine’s most prolonged and deadly crisis By 2010, Ukraine’s fifty richest people since its post-Soviet independence began as a controlled nearly half of the country’s gross protest against the government dropping plans domestic product, writes Andrew Wilson in the to forge closer trade ties with the European CFR book Pathways to Freedom. Union, and has since spurred escalating tensions between Russia and Western powers. A reformist tide briefly crested in 2004 when The crisis stems from more than twenty years of the Orange Revolution, set off by a rigged weak governance, a lopsided economy presidential election won by Yanukovich, dominated by oligarchs, heavy reliance on brought Viktor Yushchenko to the presidency. Russia, and sharp differences between Yet infighting among elites hampered reforms, Ukraine’s linguistically, religiously, and and severe economic troubles resurged with ethnically distinct eastern and western regions. the global economic crisis of 2008. The revolution also masked the divide between After the ouster of President Viktor Yanukovich European-oriented western and central in February 2014, Russia annexed the Crimean Ukraine and Russian-oriented southern and peninsula and the port city of Sevastopol, and eastern Ukraine. deployed tens of thousands of forces near the border of eastern Ukraine, where conflict Campaigning on a platform of closer ties with erupted between pro-Russian separatists and Russia, Yanukovich won the 2010 presidential the new government in Kiev. -

Yaroslavl Roadmap 10-15-20

Yaroslavl Roadmap 10-15-20 10 Years to Implement 15 Steps to Take 20 Pitfalls to Avoid International Experience and the Path Forward for Russian Innovation Policy Israel Finland Taiwan India USA Russia The New York Academy of Sciences is the world’s nexus of scientific innovation in the service of humanity. For nearly 200 years—since 1817—the Academy has brought together extraordinary people working at the frontiers of discovery and promoted vital links between science and society. One of the oldest scientific institutions in the United States, the Academy has become not only a notable and enduring cultural institution in New York City, but also one of the most significant organizations in the international scientific community. The Academy has a three-pronged mission: to advance scientific research and knowledge, support scientific literacy, and promote the resolution of society’s global challenges through science-based solutions. Throughout its history, the Academy’s membership has featured global leaders in science, business, academia, and government, including U.S. Presidents Jefferson and Monroe, Thomas Edison, Louis Pasteur, Charles Darwin, Margaret Mead, and Albert Einstein. Today, the New York Academy of Sciences’ President’s Council includes 26 Nobel Laureates as well as CEOs, philanthropists, and leaders of national science funding agencies. For more information on The New York Academy of Sciences, please visit www.nyas.org. Ellis Rubinstein, President and CEO The New York Academy of Sciences 7 World Trade Center 250 Greenwich Street, 40th floor New York, NY 10007-2157 212-298-8600 ©The New York Academy of Sciences, August 20, 2010, All Rights Reserved Authors and Contributors Principal Authors: Dr. -

Social Media and Civil Society in the Russian Protests, December 2011

Department of Informatics and Media Social Science – major in Media and Communication Studies Fall 2013 Master Two Years Thesis Social Media and Civil Society in the Russian Protests, December 2011 The role of social media in engagement of people in the protests and their self- identification with civil society Daria Dmitrieva Fall 2013 Supervisor: Dr. Gregory Simons Researcher at Uppsala Centre for Russian and Eurasian Studies 1 2 ABSTRACT The study examines the phenomenon of the December protests in Russia when thousands of citizens were involved in the protest movement after the frauds during the Parliamentary elections. There was a popular opinion in the Internet media that at that moment Russia experienced establishment of civil society, since so many people were ready to express their discontent publically for the first time in 20 years. The focus of this study is made on the analysis of the roles that social media played in the protest movement. As it could be observed at the first glance, recruiting and mobilising individuals to participation in the rallies were mainly conducted via social media. The research analyses the concept of civil society and its relevance to the protest rhetoric and investigates, whether there was a phenomenon of civil society indeed and how it was connected to individuals‘ motivation for joining the protest. The concept of civil society is discussed through the social capital, social and political trust, e- democracy and mediatisation frameworks. The study provides a comprehensive description of the events, based on mainstream and new media sources, in order to depict the nature and the development of the movement. -

Solving the Public Diplomacy Puzzle— Developing a 360-Degree Listening and Evaluation Approach to Assess Country Images

Perspectives Solving the Public Diplomacy Puzzle— Developing a 360-degree Listening and Evaluation Approach to Assess Country Images By Diana Ingenho & Jérôme Chariatte Paper 2, 2020 Solving the Public Diplomacy Puzzle— Developing a 360-Degree Integrated Public Diplomacy Listening and Evaluation Approach to Analyzing what Constitutes a Country Image from Different Perspectives Diana Ingenhoff & Jérôme Chariatte November 2020 Figueroa Press Los Angeles SOLVING THE PUBLIC DIPLOMACY PUZZLE—DEVELOPING A 360-DEGREE INTEGRATED PUBLIC DIPLOMACY LISTENING AND EVALUATION APPROACH TO ANALYZING WHAT CONSTITUTES A COUNTRY IMAGE FROM DIFFERENT PERSPECTIVES by Diana Ingenhoff & Jérôme Chariatte Guest Editor Robert Banks Faculty Fellow, USC Center on Public Diplomacy Published by FIGUEROA PRESS 840 Childs Way, 3rd Floor Los Angeles, CA 90089 Phone: (213) 743-4800 Fax: (213) 743-4804 www.figueroapress.com Figueroa Press is a division of the USC Bookstores Produced by Crestec, Los Angeles, Inc. Printed in the United States of America Notice of Rights Copyright © 2020. All rights reserved. Except for the quotation of short passages for the purposes of criticism and review, no part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system now known or to be invented, without prior written permission from the author, care of Figueroa Press. Notice of Liability The information in this book is distributed on an “As is” basis, without warranty. While every precaution has been taken in the preparation of this book, neither the author nor Figueroa nor the USC University Bookstore shall have any liability to any person or entity with respect to any loss or damage caused or alleged to be caused directly or indirectly by any text contained in this book. -

Cyber-Diplomacy

GLOBAL AFFAIRS, 2017 https://doi.org/10.1080/23340460.2017.1414924 Cyber-diplomacy: the making of an international society in the digital age André Barrinhaa,b and Thomas Renardc,d aDepartment of Politics, Languages and International Studies, University of Bath, Bath, UK; bCentre for Social Studies, University of Coimbra, Coimbra, Portugal; cEgmont – Royal Institute for International Relations, Brussels, Belgium; dDepartment of International Affairs, Vesalius College, Brussels, Belgium ABSTRACT ARTICLE HISTORY Cyberspace has become a major locus and focus of international Received 11 July 2017 relations. Most global powers have now streamlined cyber issues Accepted 6 December 2017 into their foreign policies, adopting cyber strategies and KEYWORDS appointing designated diplomats to pursue these strategic Diplomacy; cybersecurity; objectives. This article proposes to explore the concept of cyber- cyber-diplomacy; diplomacy, by analysing its evolution and linking it to the broader international society; foreign discussions of diplomacy as a fundamental institution of policy international society, as defined by the English School of International Relations. It argues that cyber-diplomacy is an emerging international practice that is attempting to construct a cyber-international society, bridging the national interests of states with world society dynamics – the predominant realm in which cyberspace has evolved in the last four decades. By itself, the internet will not usher in a new era of international cooperation. That work is up to us. (Barack Obama, 2011) Introduction Cyber espionage, cyber-attacks, hacktivism, internet censorship and even supposedly tech- nical issues such as net neutrality are now making the headlines on a regular basis. Cyber- space has become a contested political space, shaped by diverging interests, norms and Downloaded by [Mount Allison University Libraries] at 05:24 29 December 2017 values. -

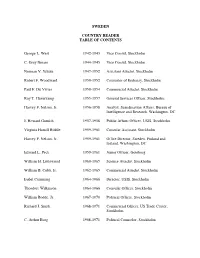

Table of Contents

SWEDEN COUNTRY READER TABLE OF CONTENTS George L. West 1942-1943 Vice Consul, Stockholm C. Gray Bream 1944-1945 Vice Consul, Stockholm Norman V. Schute 1947-1952 Assistant Attaché, Stockholm Robert F. Woodward 1950-1952 Counselor of Embassy, Stockholm Paul F. Du Vivier 1950-1954 Commercial Attaché, Stockholm Roy T. Haverkamp 1955-1957 General Services Officer, Stockholm Harvey F. Nelson, Jr. 1956-1958 Analyst, Scandinavian Affairs, Bureau of Intelligence and Research, Washington, DC J. Howard Garnish 1957-1958 Public Affairs Officer, USIS, Stockholm Virginia Hamill Biddle 1959-1961 Consular Assistant, Stockholm Harvey F. Nelson, Jr. 1959-1961 Office Director, Sweden, Finland and Iceland, Washington, DC Edward L. Peck 1959-1961 Junior Officer, Goteborg William H. Littlewood 1960-1965 Science Attaché, Stockholm William B. Cobb, Jr. 1962-1965 Commercial Attaché, Stockholm Isabel Cumming 1964-1966 Director, USIS, Stockholm Theodore Wilkinson 1964-1966 Consular Officer, Stockholm William Bodde, Jr. 1967-1970 Political Officer, Stockholm Richard J. Smith 1968-1971 Commercial Officer, US Trade Center, Stockholm C. Arthur Borg 1968-1971 Political Counselor, Stockholm Haven N. Webb 1969-1971 Analyst, Western Europe, Bureau of Intelligence and Research, Washington, DC Patrick E. Nieburg 1969-1972 Public Affairs Officer, USIS, Stockholm Gerald Michael Bache 1969-1973 Economic Officer, Stockholm Eric Fleisher 1969-1974 Desk Officer, Scandinavian Countries, USIA, Washington, DC William Bodde, Jr. 1970-1972 Desk Officer, Sweden, Washington, DC Arthur Joseph Olsen 1971-1974 Political Counselor, Stockholm John P. Owens 1972-1974 Desk Officer, Sweden, Washington, DC James O’Brien Howard 1972-1977 Agricultural Officer, US Department of Agriculture, Stockholm John P. Owens 1974-1976 Political Officer, Stockholm Eric Fleisher 1974-1977 Press Attaché, USIS, Stockholm David S. -

Soviet Foreign Minister Andrei Gromyko and Sweden by Sven Hirdman

KUNGL KRIGSVETENSKAPSAKADEMIENS HANDLINGAR OCH TIDSKRIFT DISKUSSION & DEBATT Soviet Foreign Minister Andrei Gromyko and Sweden by Sven Hirdman ormer Soviet Foreign Minister Andrei The relations between Sweden and the FGromyko, whose 100th birthday is Soviet Union got on to a new footing commemorated this year, had several con- when, in April 1956, Prime Minister Tage tacts with Sweden from 1948 until 1984. Erlander and his coalition partner Minister To Swedish diplomats he was a very well- for the Interior, Gunnar Hedlund, paid known figure and, I would say, a respected an official visit to the Soviet Union – the statesman. I met him on a few occasions, first ever by a Swedish Prime Minister. As as described below. First Deputy Foreign Minister, Gromyko Andrei Gromyko’s first contact with should have participated in this event. Sweden was in 1948. He was then the So- Substantial talks took place with the Soviet viet Representative to the United Nations. Government, led by Nikita Khrushchev Suddenly, he had to return to Moscow for and Nikolai Bulganin, on international is- family reasons and boarded the Swedish sues and on Swedish – Russian relations, Atlantic liner Gripsholm, being the fastest including the well-known Raoul Wallen- connection. Had he, as originally planned, berg case. A year later, in February 1957, taken the Soviet ship Pobeda, he would it was Gromyko who handed the Swedish have suffered disaster, as the Pobeda Ambassador in Moscow, Mr Rolf Sohl- caught fire in the Black Sea and many pe- man, a note saying that Wallenberg had ople died. Gromyko describes the incident died in the Lyubyanka prison in July 1947.