Case Australian Wine (B) the Barossa Cluster

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Layer Cake Fact Tech Sell Sheet Working File MASTER.Indd

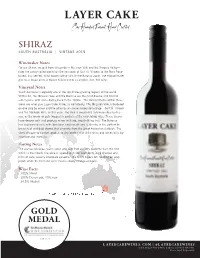

SHIRAZ SOUTH AUSTRALIA | VINTAGE 2015 Winemaker Notes For our Shiraz, we pull from vineyards in McLaren Vale and the Barossa Valley— from the sandy-soiled blocks on the sea coast of Gulf St. Vincent to the Terra Rosa- based, tiny-berried, wind-blown rolling hills in the Barossa Zone. The microclimates give us a broad array of fl avors to blend into a complex, rich, full wine. Vineyard Notes South Australia is arguably one of the top Shiraz-growing regions of the world. Within SA, the McLaren Vale and the Barossa are the most diverse and historic sub-regions, with vines dating back to the 1830s. The microclimates within these areas are what give Layer Cake Shiraz its complexity. The McLaren Vale is bordered on one side by water and the other by an ancient mountain range – Gulf St. Vincent and the Adelaide Hills, in this case. The Vale is moderated in temperature by the sea, as the warm air gets trapped in pockets of the undulating hills. These blocks have deeper soils and produce wines with big, mouth-fi lling fruit. The Barossa has shallow red soils with limestone underneath and is directly in the path of the brutal heat and dust storms that emanate from the Great Australian Outback. The vines struggle to survive, producing tiny berries with thick skins and wines with big structure and intensity. Tasting Notes The aromas of cocoa, warm spice and dark fruit are very powerful from the fi rst whiff. In the mouth, the wine is layered with rich blackberry, dark cherries and hints of dark, creamy chocolate ganache. -

2019 BAROSSA WINE SHOW RESULTS CA TALOGUE Ne

#BarossaWS19 | #barossa |#barossawine |#barossa #BarossaWS19 SHARE THE GOODNEWS: 2019 BAROSSA WINE SHOW RESULTS CATALOGUE 42nd43rd BarossaBarossa WineWine ShowShow Major Sponsors 20192018 Barossa Wine Show Results Catalogue printed by: Judges & Committee Judges Committee Chairman of Judges Wine of Provenance Committee Chair Nick Ryan Judges Andrew Quin, Hentley Farm Andrew Wigan Panel Chair Judges Phil Reedman Committee PJ Charteris Louisa Rose Alex MacClelland, Bethany Wines Sue Bell Amanda Longworth, Adam Wadewitz Wine of Provenance Barossa Grape & Wine Association Associate Judge Bernadette Kaeding, Rojomoma Judges Katie Spain John Hughes, Rieslingfreak Mark Pygott, MW Peter Kelly, Thorn-Clarke Wines Tash Mooney Richard Langford, Two Hands Wines Phil Lehmann Brock Harrison, Elderton Wines Tim Pelquest-Hunt Will John, Yalumba Adrian Sparks Marie Clay, Treasury Wine Estates Kelly Wellington Helen McCarthy, Mountadam Vineyards Dave Bursey, Henschke Wines Associate Judges Mark Bulman Kate Hongell Ben Thoman Angus Seabrook Clare Dry Simon Mussared Greg Clack Caitlin Brown Brooke Blair Premium Section CLASSES 1 to 20 For wines vintaged from grapes grown in the Barossa Valley (Minimum 85%) Fortified Section CLASSES 21 to 24 For fortified wines vintaged from grapes grown in the Barossa Valley (Minimum 85%). Wines not necessarily commercially available. BAROSSA WINE SHOW 2019 1 RESULTS CATALOGUE Trophies 2019 Winners THE PERNOD RICARD WINEMAKERS - L HUGO GRAMP MEMORIAL TROPHY Best 2019 Riesling, Class 1 Class 1 – Entry 23 – 2019 Dandelion Vineyards -

The Wine Industry Embraces Efficiency

www.ecosmagazine.com Published: 2009 The wine industry embraces efficiency Penelope Smith The latest environmental innovation across the wine industry was a topic of discussion and comparison at the recent 2009 Winery Engineering conference held in the beautiful Barossa Valley. Credit: iStockphoto Peter Policki, Technical Engineering Manager at Orlando Wines (the parent company for Pernod Ricard Pacific, makers of Jacob’s Creek and Wyndham Estate), says ‘Wine Delivery Automation’ has enabled his company to slash water consumption in its Jacob’s Creek winery at Rowland Flat in the Barossa by nearly 30 per cent. At each of the main transfer points in the winemaking process – from the vineyards, to trucks, to crushing, to fermentation, to centrifuge, to blending, to filtration, to oak, and then to bottling – there is the potential to lose significant volumes of wine when it is transferred through a pipe, and then pushed out with water. By introducing an automated mobile pump to deliver the wine from the source tank to 10 bottling tanks, Orlando Wines reduced unnecessary transfers, accidental wine overflows and water consumption. ‘Waterless transfers are having a significant benefit from the point of view of both wine quality and wastewater management,’ Mr Policki said. Michael Pecar is responsible for reducing energy and water use by 10 per cent across Foster’s Group’s 10 Australian production facilities, which includes its wineries (Wolf Blass and Lindemans) and breweries. This is no small task – based on 2007 figures, Foster’s total annual energy use was 1.74 Petajoules. One Petajoule is roughly 30 million kilowatt hours. -

WINE | BEVERAGE Wines by the Glass

WINE | BEVERAGE Wines By The Glass Champagne & Sparkling Wine NV Perrier-Jouët Grand Brut Champagne Epernay, France 28 NV Carpene Malvolti Prosecco Veneto, Italy 15 White 2017 Grant Burge Frizzante Moscato Barossa Valley, SA 11 2017 Ra Nui Sauvignon Blanc Marlborough,NZ 12 2018 Kaesler Old Vine Semillon Barossa Valley, SA 13 2018 Kilikanoon Skilly Valley Pinot Gris Clare Valley, SA 14 2017 Howard Park Miamup Chardonnay Margaret River, WA 14 2016 Jim Barry Single Vinyard Riesling Clare Valley, SA 17 Red 2016 Round Two Merlot Barossa Valley, SA 12 2016 Rufus Stone Shiraz Heathcote, VIC 13 2015 Howard Park Flint Rock Syrah Margaret River, WA 14 2016 Barossa Valley Estate Cabernet Sauvignon Barossa Valley, SA 16 2016 Catena Malbec Mendoza, Argentina 16 2016 Abels Tempest Pinot Noir Derwent Valley, TAS 19 2016 Tyrrells Stevens Shiraz Hunter Valley, NSW 17 2015 Rockford Rod & Spur Shiraz Cabernet Barossa Valley, SA 26 Rosé 2017 Teusner Salsa Rosé Mourvedre Barossa Valley, SA 12 Half Bottles NV Laurent Perrier Piccolo 200ml Champagne Epernay, France 40 NV Pol Roger Brut Reserve Champagne Epernay, France 74 2014 Brokenwood Semillon Hunter Valley, NSW 36 2017 ATA Rangi Crimson Pinot Noir Martinbourough, NZ 45 2012 Cannonball Cabernet Sauvignon California, USA 50 2015 Rusden Black Guts Shiraz Barossa Valley ,SA 95 Vintages are subject to avalability & may change without notice. Prices are inclusive of GST. Cocktails Manly Caipiroska Fresh lime & sugar muddled then shaken with Manly Spirits Botanical Vodka & poured over crushed ice. 18 Cosmopolitan Absolut Citron Vodka, Cointreau & cranberry juice shaken with a squeeze of fresh lime. 18 Montenegro Twist on a classic. -

2021 Barossa Wine Auction Catalogue Here

In April 2021, Barossa Grape & Wine Association together with Langton’s Fine Wines, present Australia’s most prestigious regional wine auction. An integral part of the Partnering with Langton’s Barossa Vintage Festival Fine Wine Auction House, since 1965, the Barossa the Barossa Wine Auction Wine Auction has now brings you an exclusive grown to become opportunity to access Australia’s premier rare and covetable wines. regional wine auction. Provenance is assured, with wines sourced directly from the winery and winemaker’s own collections. Barossa Wine Auction 2020 2 Barossa Live Auction Page 5-11 (auction lots beginning ‘B’) Friday 16 April 2021 Tickets $50pp includes Eden 9.30 am – 12.30pm Valley Riesling and Oysters on arrival and light refreshments Chateau Tanunda throughout. Basedow Road _ Tanunda, SA www.barossavintagefestival.com.au Sydney Live Auction Page 13-19 (auction lots beginning ‘S’) Dinner Thursday 29 April 2021 Hyatt Regency Sydney, NSW Tickets to be released in early 2021 Online Auction Page 21-31 (auction lots beginning ‘W’) Opens Friday 9 April 2021 Closes Sunday 2 May 2021 At langtons.com.au Barossa Wine Auction 2020 3 Barossa Live Auction o LOT N- Winery Barossa Bottle Set of 9 Vintage MV Price Guide $7000.00 - 8000.00 B01 Quantity 1 An extremely rare, highly collectable set of ultra fine Barossa wines, each one awarded a perfect 100 points, includes: 1 x 375ml BOTTLE of Seppeltsfield 1921 100 Year Old Para Vintage Tawny (Halliday) 1 x BOTTLE of Torbreck 2016 RunRig Shiraz Viognier (Joe Czerwinski) 1 x BOTTLE of Torbreck 2012 The Laird Shiraz (Robert Parker) 1 x BOTTLE of Penfolds 2013 Bin 95 Grange (Wine Spectator) 1 x BOTTLE of Chris Ringland 2002 Shiraz (Robert Parker) 1 x BOTTLE of Greenock Creek 1998 Roennfeldt Road Cabernet (Robert Parker) 1 x BOTTLE of Greenock Creek 1998 Roennfeldt Road Shiraz (Robert Parker) 1 x BOTTLE of Henschke 2015 Hill of Grace Shiraz (Wine Spectator/ Andred Caillard MW) 1 x BOTTLE of Standish Wine Co. -

5008 Wine Regions (Page 1)

Wine Australia fact sheet Wine Regions - Australia’s famous wine regions 1 While Australia has about Clare Valley Most Coonawarra Cabernets Since those pioneering days, 60 wine regions, the The Clare Valley is considered will effortlessly cellar for at the Hunter’s wine industry has following ten are among to be among South Australia’s least 10 years, but that’s not flourished and now more than its most famous and most picturesque regions. It is the only variety the region is 80 wineries and cellar doors diverse. From the rugged also known as the home of famous for. Other award are open to tourist traffic en and isolated beauty of Australian Riesling and with winning varietals are Shiraz, route from Sydney. Margaret River in good reason – Clare’s Merlot and Chardonnay. Winemakers in the Hunter Western Australia, to consistency in making have found success with the historical home of Rieslings of exceptional Heathcote varieties such as Shiraz, Australian wine, the quality and style has won Rapidly raising the bar in terms Verdelho and Chardonnay, but Hunter Valley in New loyal consumers internationally. of elegance and complexity, no other region has developed South Wales, a journey particularly with Shiraz, such an affinity with Semillon. across Australia’s wine Clare is not only famous for Heathcote’s climate and soils regions is filled with a Riesling; it also produces of this Victorian region are Semillons from the Hunter diversity of climates, award-winning Cabernet strongly influenced by the Mt Valley have great capacity for soils, elevation and – Sauvignon and Shiraz that Camel Range which creates a graceful ageing, particularly in ultimately – wine styles. -

Drinks Drinks Package

DRINKS DRINKS PACKAGE Lunch 1 hour | $17 per guest 2 hours | $22 per guest 3 hours | $26 per guest Dinner 3 hours | $34 per guest Cocktail 4 hours | $39 per guest 1 hour | $21 per guest 5 hours | $44 per guest 2 hours | $27 per guest 3 hours | $35 per guest 4 hours | $46 per guest 5 hours | $49 per guest Sparkling Little Leaf Sparkling by Wolf Blass White Wine Little Leaf Sauvignon Blanc by Wolf Blass Red Wine Little Leaf Shiraz by Wolf Blass Draught Beer Hahn Super Dry, Hahn Premium Soft Drinks, Orange Juice, Mineral Water Hilton Perth 2015 Hilton Perth 2019 UPGRADE YOUR WINE GOLD PACKAGE Choose one red & one white| $7 per guest Angas Brut sparkling Hartog’s Plate Sauvignon Blanc Semillon Seppelt The Drive Chardonnay Seppelt The Drive Shiraz Hartog’s Plate Cabernet Merlot PLATINUM PACKAGE Choose one red & one white| $10 per guest Angas Brut sparkling Mawson’s Cape Denison Sauvignon Blanc Vasse Felix Classic Dry White West Cape Howe Cape to Cape Chardonnay T’Gallant Cape Schanck Pinot Noir Earthworks Barossa Cabernet Sauvignon Yalumba Organic Shiraz Hilton Perth 2019 BEER, SPIRITS, PORT, LIQUEURS, SOFT DRINKS BOTTLED BEERS SOFT DRINKS & JUICES Carlton Dry $7.50 Soft drinks, jug $15 Corona $8.50 Soft drinks, glass $5 Little Creatures Pilsner $9.00 Fruit juice, jug $18 Fruit juice, glass $6 DRAUGHT BEERS Hahn Premium Light $5.50 PORT BY THE GLASS Hahn Super Dry $6.50 Penfolds Club $5 Little Creatures Pale Ale $8.50 Yalumba Galway Pipe $7 Mr. Pickwick $9 Additional beer options are available on request. -

Integrated Annual Report FY20

Integrated Annual Report FY20 Naturally committed Carte Blanche to Sanja “I stage landscapes and people, then I transform them to create an imaginary universe.” Marušić A Pernod Ricard employee and a partner, linked by a resource that is This year, Pernod Ricard essential to our products. For our eleventh artistic campaign, Sanja Marušić gave Carte Blanche shows how these collaborations unfold in their respective environments. to the Dutch-Croatian photographer Sanja Dressed in costumes that the photographer has made herself, they Marušić. are transformed into human sculptures set in natural landscapes. Her experimental approach to materials, colour, composition and choreography www.sanjamarusic.com creates dreamlike scenes that project an otherworldly aura. Adeline Loizeau, A shared EDV and Wine Supply Manager, Maison Martell commitment Grapes Creating moments of conviviality out of nature and the resources it provides. That is the ethos we actively share with our partners across the entire value chain, as exemplified by Cork these portraits of employees and Pernod Ricard partners. Laurence Prulho, Director, La Perruge Vineyards & Distillery Luis Torres, Paul McLaughlin, Conchi Garzón, Owner of Rancho Owner, Sales Director, La Garita Kelvin Cooperage MASILVA & Garzón Estibaliz Torrealba, Agave Sustainable Performance Manager, Oak Pernod Ricard Winemakers Finbarr Curran, Bond Supervisor, Irish Distillers Asbel Morales, Maestro del Ron Cubano Stefania Elizalde, Liquids Coordinator, Virginie Bartholin, House of Tequila Alejandro Sugar Purchasing -

Varieties Barossa Chapters

Barossa Chapters Varieties Barossa Chapters Varieties Barossa owes much to Europe. Its name, cultural instincts, languages, food, viticultural and winemaking heritage, are all transportations that have been moulded and honed by 175 years of Australian innovation. Cover Image: Robert Hill-Smith & Louisa Rose Yalumba Barossa One could be forgiven for thinking Entrepreneurs with big visions built white wines such as Riesling and Barossa was settled by the Spanish. stone wineries and started making Chardonnay as well as medium body Its name can certainly be traced fortified “ports” and “sherries” as well reds such as Shiraz and Cabernet. back to the windswept Barrosa Ridge as fine table wines called “claret” and Now Barossa is the most recognised in the Spanish region of Andalusia “hermitage” and “burgundy”, paying name in Australian winemaking, due to where in March 1811 Lieutenant homage to European tradition. Barossa its forgiving viticultural environment, General Thomas Graham of the became the largest wine-producing its treasure-trove of century old British Army defeated the French region in Australia by the turn of the pre-phylloxera vines and its six Marshal Victor, during the Napoleonic century, sustaining a community of generations of grapegrowing and Peninsular Wars. grapegrowers, winemakers, cellar winemaking heritage. hands and coopers and earning Graham received a peerage and significant export income for the state But it has also evolved over 175 years was named Lord Lynedoch but it was of South Australia. into much more than a wine region. his young aide-de-camp Lieutenant Old Silesian cultural food traditions William Light who was to remember Through the 20th century Barossa had continue to be celebrated, such as the the name. -

COONAWARRA \ Little Black Book Cover Image: Ben Macmahon @Macmahonimages COONAWARRA \

COONAWARRA \ Little Black Book Cover image: Ben Macmahon @macmahonimages COONAWARRA \ A small strip of land in the heart of the Limestone Coast in South Australia. Together our landscape, our people and our passion, work in harmony to create a signature wine region that delivers on a myriad of levels - producing wines that unmistakably speak of their place and reflect the character of their makers. It’s a place that gets under your skin, leaving an indelible mark, for those who choose it as home and for those who keep coming back. We invite you to Take the Time... Visit. Savour. Indulge. You’ll smell it, taste it and experience it for yourself. COONAWARRA \ Our Story Think Coonawarra, and thoughts of There are the ruddy cheeks of those who tend the vines; sumptuous reds spring to mind – from the the crimson sunsets that sweep across a vast horizon; and of course, there’s the fiery passion in the veins of our rich rust-coloured Terra Rossa soil for which vignerons and winemakers. Almost a million years ago, it’s internationally recognised, to the prized an ocean teeming with sea-life lapped at the feet of the red wines that have made it famous. ancient Kanawinka Escarpment. Then came an ice age, and the great melt that followed led to the creation of the chalky white bedrock which is the foundation of this unique region. But nature had not finished, for with her winds, rain and sand she blanketed the plain with a soil rich in iron, silica and nutrients, to become one of the most renowned terroir soils in the world. -

Either Hugo, Or I Go

WIN Drink to a beer’s long life NE of Australia’s most famous brands has had a major Mac’s, New Zealand’s original craft makeover. Not only has it given beer, turns 30 this month, and Oits label a bit of nip-and-tuck and wants everyone to join in as it indulged in an expensive set of celebrates. extensions; it’s also visited the local Production of council chambers, filled out the forms Mac’s began in and instigated a name change. a small First launched in 1980 and designed to microbrewery age for a decade or more, St Hugo was in Nelson in until 2008 always made from cabernet 1981 and, since sauvignon sourced from a multitude of then, the brand vineyards in South Australia’s famous has gone from Coonawarra terra rossa soils. strength to Not content with being known solely strength. It as a world-class Coonawarra cabernet now boasts an sauvignon, the St Hugo brand has extended recently been extended to include two family of wines from the Barossa, a shiraz and a naturally GSM ( grenache, shiraz and mataro) brewed beers, blend. ciders and non-alcoholic drinks, The ‘‘Orlando’’ moniker on the iconic each with its own personality and label has also been subtly sidelined and taste. replaced with ‘‘Jacob’s Creek’’. The In October 2006, Wellington’s Jacob’s Creek brand needs no Shed 22 brewpub, The Brewery Bar introduction but some may not know that and Restaurant, was refurbished to those wines are made by Orlando Wines, become the first Mac’s Brewbar. -

Illustrative Projects of 2012 - 2013

Illustrative projects of 2012 - 2013 H ighlights 2012 - 2013 $21 million water Jam Factory to infrastructure be established in Future Leaders project received the Barossa $10.7 million Programme future support 107 jobs created Be Consumed – Region wins in business Barossa $6 priority within assisted Million Tourism NBN 3 year Campaign rollout Place Barossa Career Management SService trains & 536 Businesses for Township & refocusses ffor assisted renewal transition iIndustries Regional Township Development Economic South Australia Development Conference workshops TAFE Virtual Thinking Barossa Enterprise – Big Ideas for partner Innovating High H ighlights 2012 - 2013 82 workshops Young people in 1391 agriculture Events strategy participants network established 62 businesses assisted to Cycle Tourism innovate Strategy Disability & Live Music 12 Tourism Aged Care Thinker in Infrastructure Cluster Residence projects assisted established to win grant funding Workforce audit World Heritage Regional for transferable status – project Development skills assists 135 management Grants - businesses group Gawler & Light Northern FACETS Barossa: Adelaide Plains Broadband linked Horticultural National multi-site Conference lights Futures Outcome 1: Community and Economic Development Infrastructure: The Greater Gawler Water Reuse Scheme RDA Barossa has collaborated with The Wakefield Group and regional councils in a strategic project to drive economic diversity and sustainable water resources into the future under the South Australian Government’s 30 Year Plan for Greater Adelaide. It is forecast that the population will increase by 74,400 by 2040 and employment by 38,500 jobs. The focus for the population growth is Greater Gawler/Roseworthy and the employment is led by intensive agriculture, its processing and distribution with a new irrigation area proposed north of Two Wells in the west with other areas adjacent to Gawler intensifying to increase production.