The 1623 Shakespeare First Folio: a Minority Report (2016) a Special Issue of Brief Chronicles - First Folio Special Issue (2016) Ii

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Proem Shakespeare S 'Plaies and Poems"

Proem Shakespeare s 'Plaies and Poems" In 1640, the publisher John Benson presents to his English reading public a Shakespeare who is now largely lost to us: the national author of poems and plays. By printing his modest octavo edition of the Poems: Written By Wil. Shake-speare. Gent., Benson curiously aims to complement the 1623 printing venture of Shakespeare's theatre colleagues, John Heminge and Henry Condell , who had presented Mr. William Shakespeares Comedies, Histories, & Tragedies in their monumental First Folio. Thus, in his own Dedicatory Epistle "To the Reader," Benson remarks that he presents "some excellent and sweetly composed Poems," which "had nor the fortune by reason of their lnfancie in his death, to have the due accommodation of proportionable glory, with the rest of his everliving Workes" (*2r). Indeed, as recent scholarship demonstrates, Benson boldly prints his octavo Poems on the model ofHeminge and Condell 's Folio Plays. ' Nor simply does Benson's volume share its primer, Thomas Cores, wirh rhe 1632 Folio, bur both editions begin with an identical format: an engraved portrait of the author; a dedicatory epistle "To the Reader"; and a set of commendatory verses, with Leonard Digges contributing an impor tant celebratory poem to both volumes. Benson's engraving by William Marshall even derives from the famous Martin Droeshout engraving in the First Folio, and six of the eight lines beneath Benson's engraving are borrowed from Ben Jonson's famed memorial poem to Shakespeare in char volume. Accordingly, Benson rakes his publishing goal from Heminge and Conde!!. They aim to "keepe the memory of such worthy a Friend, & Fellow alive" (Dedicatory Epistle to the earls ofPembroke and Montgomery, reprinted in Riverside, 94), while he aims "to be serviceable for the con tinuance of glory to the deserved Author" ("To the Reader," *2v). -

First Folio Table of Contents the Tragedie of Cymbeline

THE TRAGEDIE OF CYMBELINE. by WILLIAM SHAKESPEARE Based on the Folio Text of 1623 DjVu Editions E-books © 2001, Global Language Resources, Inc. Shakespeare: First Folio Table of Contents The Tragedie of Cymbeline . 1 Actus Primus. Scoena Prima. 1 Scena Secunda. 3 Scena Tertia. 6 Scena Quarta. 7 Scena Quinta. 8 Scena Sexta. 12 Scena Septima. 14 Actus Secundus. Scena Prima. 20 Scena Secunda. 21 Scena Tertia. 22 Scena Quarta. 26 Actus Tertius. Scena Prima. 32 Scena Secunda. 34 Scena Tertia. 36 Scena Quarta. 38 Scena Quinta. 43 Scena Sexta. 47 Scena Septima. 48 Scena Octaua. 50 Actus Quartus. Scena Prima. 51 Scena Secunda. 51 Scena Tertia. 62 Scena Quarta. 63 Actus Quintus. Scena Prima. 65 Scena Secunda. 66 Scena Tertia. 67 Scena Quarta. 69 Scena Quinta. 74 - i - Shakespeare: First Folio The Tragedie of Cymbeline The Tragedie of Cymbeline zz3 Actus Primus. Scoena Prima. 2 Enter two Gentlemen. 3 1.Gent. 4 You do not meet a man but Frownes. 5 Our bloods no more obey the Heauens 6 Then our Courtiers: 7 Still seeme, as do’s the Kings. 8 2 Gent. But what’s the matter? 9 1. His daughter, and the heire of’s kingdome (whom 10 He purpos’d to his wiues sole Sonne, a Widdow 11 That late he married) hath referr’d her selfe 12 Vnto a poore, but worthy Gentleman. She’s wedded, 13 Her Husband banish’d; she imprison’d, all 14 Is outward sorrow, though I thinke the King 15 Be touch’d at very heart. 16 2 None but the King? 17 1 He that hath lost her too: so is the Queene, 18 That most desir’d the Match. -

Shakespeare's First Folio

SHAKESPEARE’S FIRST FOLIO DR. SARAH HIGINBOTHAM GEORGIA INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY OVERVIEW Fall 2016 F2 9:35-10:55 TR Clough 325 D4 1:35-2:55 TR Clough 127 Seven years after William Shakespeare died, one of the world’s most N 12:05-1:25 TR Skiles 308 important books was published: a collection of thirty-six of his plays E-Mail: [email protected] that we now call the “First Folio.” Without the First Folio, we would Office: Stephen C. Hall Building 009 not have Julius Caesar, Macbeth, The Taming of the Shrew, or two plays that have profoundly changed the way that I think, Measure for Measure and Twelfth Night. We also wouldn’t have the iconic stage direction, “exit, pursued by a bear” (The Winter’s Tale). As Georgia Tech phases out its MATERIALS physical library, and as the world celebrates the 400th anniversary of Shakespeare’s death with a First Folio tour, this course will investigate what the First Folio affords us in the twenty-first century. REQUIRED But while Shakespeare is our topic, our goals concern communication Henry V Folger Shakespeare Library, 2009 skills and critical thinking: you will learn to identify relevant questions Hamlet about an issue, synthesize multiple perspectives, assess the soundness of Folger Shakespeare Library, 2005 a position, revise your work based on feedback, and apply your research King Lear to real world issues. The course will also help you formulate and defend Modern Library Classics, 2009 your point of view via written essays, oral presentations, visual analysis, WOVENText and through electronic and nonverbal communication. -

Romeo-And-Juliet-1596480840.Pdf

Romeo and Juliet by Rebecca Olson is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted. Contents ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS v PREFACE vii INTRODUCTION x LIST OF MAIN CHARACTERS xvi ACT 1 1 ACT 2 43 ACT 3 80 ACT 4 122 ACT 5 146 GLOSSARY 169 CREATIVE COMMONS LICENSE 180 RECOMMENDED CITATIONS 181 VERSIONING 183 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Many thanks to Open Oregon State for publishing and funding this edition, and the OSU School of Writing, Literature, and Film for financial and administrative support. The Oregon Shakespeare Festival made our field trip to Ashland to see Othello both feasible and memorable. And we are much indebted to the teachers and students who took the time to answer our questions and share experiences and lesson plans—thank you! Tessa Barone, Justin Bennett, Ethan Heusser, Aleah Hobbs, and Benjamin Watts served as lead editors for the project. Shannon Fortier, a recent OSU graduate, donated her time and talents. Jac Longstreth (a Biochemistry and Biophysics major!) provided a great deal of research and editing support, funded by the URSA Engage program at OSU. Jessie Heine was our graduate intern extraordinaire. Emily Kirchhofer designed the cover (deftly incorporating an abundance of ideas and opinions). Michelle Miller and Marin Rosenquist completed much of the late-stage editing and also promoted the project at the 2018 OSU Undergraduate Humanities Research Conference. The editors drew on editing work completed by their peers in ENG 435/535 (Fall 2017). And special thanks to Dr. Lara Bovilsky, who in January 2016 generously donated her time to lead ENG 435 students through the University of Oregon’s exhibit devoted to the First Folio (now an online exhibit Time’s Pencil); the student projects that resulted from that class inspired this textbook. -

Life Portraits Illian Si Ak Hart

LI F E PO RT RA I T S ” T I L L I A N S I A K H A R A HI ST O RY O F THE VAR OU RE RE ENTAT ON OF THE OET WI TH A N I S P S I S P , I N T R A T ENT TY E" A MI NAT I ON TO H E I U H I C I . 6 x 9/ B “ Y . HA N y I FR I SWE L L . ' ’ ‘ ’ ’ ’ [llzzslratm é " Pfi oto ra fis o th e most a utfiemz c Pan m z fs and wz flz ) g p f , Views "f a é C ND D NE C O . , " U ALL, OW S , T H E F F L T O N H E A D O F S B A K S P RA R F L O N D N A M P L W N O S S O N O , SO , A H L x LU DG TE L . 4 , I 1 8 64 . L O N DO N R G AY S O N A N D A \ LO P I E S , T R , R NT R , BR E A D S TR E E T H I L L THE RE SI DENT P , V C E - R E D E N T I P S I S , AND BROT HE R M EMBERS OF T HE C OMMITT EE FO R RA ISING A NAT I ONA L M EMORI A L T O P E A R E S H A K S , T HIS VOLU M E IS D EDI CAT ED BY R T HE A UT HO . -

The Nature of Stage Directions in the First Folio

THE NATURE OF STAGE DIRECTIONS IN THE FIRST FOLIO OF SHAKESPEARE -..L.c..:'~ / .~ A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the Department of English and the Graduate Council of the Kansas State Teachers College of Emporia In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts by Joan E. VanSickle ::::::" November 8, 1972 , ,< ,~. T), c.~ I .. '.i (I "! { I , Iii, / \'-i co~_~ vedJr t.he/C)' partment ----..r-' /'\ . 0. (~,.,'/ ' / ;';--'; A I:' L-~_ L ~ J __ Graduate Council 331.815 / PREFACE As is readily apparent to any reader of Shakespeare's folio or quarto plays, stage directions are minimal and, at times, almost entirely absent. Quite wisely, therefore, modern editors of Shakespeare have added stage directions to assist readers to an understanding of the stage action. It is not the purpose of this author to comment further upon these editorial additions~ many scholars have already widely discussed and deliberated the accuracies, and inaccuracies, of these later emendations to Shakespeare's own directions. It is, rather, the intent of this author to pursue a study of the stage directions written in Shakespeare's First Folio (1623). Because there are so few stage directions printed, the matter of interpretation and definition of stage action in these plays has become a matter of scholastic concern. Naturally, the study of staging involves more than simply a direct textual study of the stage directions. One must also consider Shakespeare's life and its influence on his plays, the nature of his acting companies and actors, the physical iv and psychological composition of Elizabethan audiences, and 'the structure of the theatres--especially the Globe Theatre, where most of the plays were enacted. -

"A Sharers' Repertory." Rethinking Theatrical

Syme, Holger Schott. "A Sharers’ Repertory." Rethinking Theatrical Documents in Shakespeare’s England. Ed. Tiffany Stern. London: The Arden Shakespeare, 2020. 33–51. Bloomsbury Collections. Web. 26 Sep. 2021. <http://dx.doi.org/10.5040/9781350051379.ch-002>. Downloaded from Bloomsbury Collections, www.bloomsburycollections.com, 26 September 2021, 08:28 UTC. Copyright © Tiffany Stern and contributors 2020. You may share this work for non-commercial purposes only, provided you give attribution to the copyright holder and the publisher, and provide a link to the Creative Commons licence. 2 A Sharers’ Repertory Holger Schott Syme Without Philip Henslowe, we would know next to nothing about the kinds of repertories early modern London’s resident theatre companies offered to their audiences. As things stand, thanks to the existence of the manuscript commonly known as Henslowe’s Diary , scholars have been able to contemplate the long lists of receipts and expenses that record the titles of well over 200 plays, most of them now lost. The Diary gives us some sense of the richness and diversity of this repertory, of the rapid turnover of plays, and of the kinds of investments theatre companies made to mount new shows. It also names a plethora of actors and other professionals associated with the troupes at the Rose. But, because the records are a fi nancier’s and theatre owner’s, not those of a sharer in an acting company, they do not document how a group of actors decided which plays to stage, how they chose to alternate successful shows, or what they, as actors, were looking for in new commissions. -

Shakespeare's Impossible Doublet

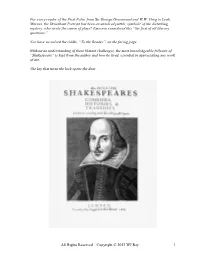

Rollett - The Impossible Doublet 31 Shakespeare’s Impossible Doublet: Droeshout’s Engraving Anatomized John M. Rollett Abstract The engraving of Shakespeare by Martin Droeshout on the title page of the 1623 First Folio has often been criticized for various oddities. In 1911 a professional tailor asserted that the right-hand side of the poet’s doublet was “obviously” the left-hand side of the back of the garment. In this paper I describe evidence which confirms this assessment, demonstrating that Shakespeare is pictured wearing an impossible garment. By printing a caricature of the man from Stratford-upon-Avon, it would seem that the publishers were indicating that he was not the author of the works that bear his name. he Exhibition Searching for Shakespeare,1 held at the National Portrait Gallery, London, in 2006, included several pictures supposed at one time or another Tto be portraits of our great poet and playwright. Only one may have any claim to authenticity — that engraved by Martin Droeshout for the title page of the First Folio (Figure 1), the collection of plays published in 1623. Because the dedication and the address “To the great Variety of Readers” are each signed by John Hemmings and Henry Condell, two of Shakespeare’s theatrical colleagues, and because Ben Jonson’s prefatory poem tells us “It was for gentle Shakespeare cut,” the engraving appears to have the imprimatur of Shakespeare’s friends and fellows. The picture is not very attractive, and various defects have been pointed out from time to time – the head is too large, the stiff white collar or wired band seems odd, left and right of the doublet don’t quite match up. -

2011 As You Like It

AS YOU LIKE IT Study Guide - 2011 Season Production E DIRECT AT SPEAK MACBETH THAISAGROW PROSPERO TOUCHSTONE JULIET CRE VIEW TEACH SEE CREATE HAMLET DISCUSS CLEOPATRA SEE LISTEN LAUGHROSALIND PLAY DIRECT SHYLOCKCRE LEARN CAESAR A AT ACT TEACH E OTHELLO OPHELI A Message from the Director are transformed by encountering what is “down the rabbit hole.” stark contrast to Hamlet, As IN You Like It is a play about The forest in Shakespeare’s plays is the metamorphosis of the self. always a place of transformation, a A young woman, Rosalind, is able freeing of the self from rigid societal to discover what love truly is by and parental bonds in order to pretending to be someone else, the find an authentic self. With that boy Ganymede. Through playing in mind, we have made our forest she becomes more and more into a whimsical playground where expansive, bolder and more fully objects, clothes, sound, light and herself. color are literally transformed from what they are in the court. Through Inspiration for the physical imaginative play, the characters production of As You Like It came transform themselves. from stories like The Chronicles of Narnia, Through the Looking Glass, Thank you for celebrating the and Coraline. A door is opened into human spirit with us! another world and the characters 2 Contents Shakespeare’s Life and Times ..................................................4 What Did Shakespeare Look Like? ...........................................4 Shakespeare Portrait Gallery ....................................................5 The -

Secrets of the Droeshout Shakespeare Etching

For every reader of the First Folio, from Sir George Greenwood and W.W. Greg to Leah Marcus, the Droeshout Portrait has been an unsolved puzzle, symbolic of the disturbing mystery, who wrote the canon of plays? Emerson considered this “the first of all literary questions.” Nor have we solved the riddle, “To the Reader”, on the facing page. Without an understanding of these blatant challenges, the most knowledgeable follower of “Shakespeare” is kept from the author and how he lived, essential to appreciating any work of art. The key that turns the lock opens the door. All Rights Reserved – Copyright © 2013 WJ Ray 1 Preface THE GEOMETRY OF THE DROESHOUT PORTRAIT I encourage the reader to print out the three graphics in order to follow this description. The Droeshout-based drawings are nominally accurate and to scale, based on the dimensions presented in S. Schoenbaum’s ‘William Shakespeare A Documentary Life’, p. 259’s photographic replica of the frontispiece of the First Folio, British Museum’s STC 22273, Oxford University Press, 1975. The Portrait depictions throughout the essay are from the Yale University Press’s facsimile First Folio, 1955 edition. It is particularly distinct and undamaged. In the essay that follows, a structure behind the extensive identification graphics is implied but not explained. The preface explains the hidden design. The Droeshout pictogram doubles as near-hominid portraiture, while fulfilling a profound act of allegiance and chivalric honor to Edward de Vere, 17th Earl of Oxford, by repeatedly locating his surname and title in the image. The surname identification is confirmed in Jonson’s facing poem. -

A Short History of English Printing : 1476-1900

J \ Books about Books Edited by A. W. Pollard A Short History of English Printing BOOKS ABOUT BOOKS Edited bv A. W. POLLARD POPULAR RE-ISSUE BOOKS IN MANUSCRIPT. By Falconer Madan, Bodley's Librarian, Oxford. THE BINDING OF BOOKS. By H. P. HORNE. A SHORT HISTORY OF ENGLISH PRINTING. By II. K. Plomer. EARLY ILLUSTRATED BOOKS. By A. W. POLI.ARD. Other volumes in pi-eparatioit. A Short History of English Printing 1476-1900 By Henry R. Plomer London Kegan Paul, Trench, Triibncr & Co., Ltd. Broadway House, 68-74 Carter Lane, E.C, MDCCCCXV I-'irst Edition, 1900 Second (Popular) Edition, 1915 The rights of translation and of reproduction are reserved Editor's Preface When Mr. Plomer consented at my request to write a short history of EngHsh printing which should stop neither at the end of the fifteenth century, nor at the end of the sixteenth century, nor at 1640, but should come down, as best it could, to our ovm day, we were not without appre- hensions that the task might prove one of some difficulty. How difficult it would be we had certainly no idea, or the book would never have been begun, and now that it is Imished I would bespeak the reader's sympathies, on Mr. Plomer 's behalf, that its inevitable shortcomings may be the more generously forgiven. If we look at what has already been written on the subject the diffi- culties will be more easily appreciated. In England, as in other countries, the period in the history of the press which is best known to us is, by the perversity of antiquaries, that which is furthest removed from our own time. -

First Folio Faqs

First Folio FAQs Who published the First Folio? The First Folio was published by a London syndicate headed by Edward Blount and Isaac Jaggard, whose father William Jaggard printed it at his London printing shop. How many copies of the First Folio were printed? Most likely about 750 copies were printed, of which 233 are known today. It sold well enough that a second edition (the 1632 Second Folio) was produced nine years later. How large is the First Folio? The First Folio is about 900 pages long. Each page is about a foot tall. How much did the First Folio cost? The scholar Peter Blayney suggests that an unbound copy of the First Folio cost 15 shillings; a copy with a plain calf binding cost a pound (20 shillings), about $200 today. Are all copies of the First Folio the same? No. The First Folio was proofread as it was printed, creating small variations. Over time, some copies acquired notes and drawings. Copies were damaged; many have missing pages. Page edges were also trimmed for rebinding, so the page sizes now vary. Which eighteen plays were first published in the First Folio? All's Well That Ends Well, Antony and Cleopatra, As You Like It, The Comedy of Errors, Coriolanus, Cymbeline, Henry VI, Part 1, Henry VIII, Julius Caesar, King John, Macbeth, Measure for Measure, The Taming of the Shrew, The Tempest, TImon of Athens, Twelfth Night, Two Gentlemen of Verona, and The Winter's Tale Did Shakespeare write other plays? Yes, but not many. Besides the 36 plays in the First Folio, Shakespeare wrote Pericles and The Two Noble Kinsmen (with John Fletcher).