Mongolo-Tibetica Pragensia 12-2.Indd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Summer 2018-Summer 2019

# 29 – Summer 2018-Summer 2019 H.H. Lungtok Dawa Dhargyal Rinpoche Enthusiasm in Our Dharma Family CyberSangha Dying with Confidence LIGMINCHA EUROPE MAGAZINE 2019/29 — CONTENTS GREETINGS 3 Greetings and news from the editors IN THE SPOTLIGHT 4 Five Extraordinary Days at Menri Monastery GOING BEYOND 8 Retreat Program 2019/2020 at Lishu Institute THE SANGHA 9 There Is Much Enthusiasm and Excitement in Our Dharma Family 14 Introducing CyberSangha 15 What's Been Happening in Europe 27 Meditations to Manifest your Positive Qualities 28 Entering into the Light ART IN THE SANGHA 29 Yungdrun Bön Calendar for 2020 30 Powa Retreat, Fall 2018 PREPARING TO DIE 31 Dying with Confidence THE TEACHER AND THE DHARMA 33 Bringing the Bon Teachings into the World 40 Tibetan Yoga for Health & Well-Being 44 Tenzin Wangyal Rinpoche's 2019 European Seminars and online Teachings THE LIGMINCHA EUROPE MAGAZINE is a joint venture of the community of European students of Tenzin Wangyal Rinpoche. Ideas and contributions are welcome at [email protected]. You can find this and the previous issues at www.ligmincha.eu, and you can find us on the Facebook page of Ligmincha Europe Magazine. Chief editor: Ton Bisscheroux Editors: Jantien Spindler and Regula Franz Editorial assistance: Michaela Clarke and Vickie Walter Proofreaders: Bob Anger, Dana Lloyd Thomas and Lise Brenner Technical assistance: Ligmincha.eu Webmaster Expert Circle Cover layout: Nathalie Arts page Contents 2 GREETINGS AND NEWS FROM THE EDITORS Dear Readers, Dear Practitioners of Bon, It's been a year since we published our last This issue also contains an interview with Rob magazine. -

High Road to Lhasa Trip

Indian high road to Himalaya Sub-continent lhasa trip highligh ts Journey over the Tibet Plateau to Rongbuk Monastery and Mt. Everest Absorb the dramatic views of the north face of Everest Explore Lhasa and visit Potala Palace, former home of the Dalai Lama Delve into the rich cultural traditions of Tibet, visiting Tashilhunpo Monastery in Shigatse Traverse the Himalaya overland from the Tibetan Plateau to Kathmandu Trip Duration 13 days Trip Code: HRL Grade Adventure touring Activities Adventure Touring Summary 13 day trip, 1 night hotel in Chengdu, 7 nights basic hotels, 2 nights Tibetan lodge, 2 nights Radisson Hotel, Kathmandu welcome to why travel with World Expeditions? When planning travel to a remote and challenging destination, World Expeditions many factors need to be considered. World Expeditions has been Thank you for your interest in our High Road to Lhasa trip. At pioneering trips in the Himalaya since 1975. Our extra attention to World Expeditions we are passionate about our off the beaten track detail and seamless operations on the ground ensure that you will experiences as they provide our travellers with the thrill of coming have a memorable experience in the Indian Sub‑continent. Every trip face to face with untouched cultures as well as wilderness regions is accompanied by an experienced local leader, as well as support staff of great natural beauty. We are committed to ensuring that our that share a passion for the region, and a desire to share it with you. We unique itineraries are well researched, affordable and tailored for the take every precaution to ensure smooth logistics, with private vehicles enjoyment of small groups or individuals ‑ philosophies that have throughout your trip. -

Channel Morphology and Bedrock River Incision: Theory, Experiments, and Application to the Eastern Himalaya

Channel morphology and bedrock river incision: Theory, experiments, and application to the eastern Himalaya Noah J. Finnegan A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Washington 2007 Program Authorized to Offer Degree: Department of Earth and Space Sciences University of Washington Graduate School This is to certify that I have examined this copy of a doctoral dissertation by Noah J. Finnegan and have found that it is complete and satisfactory in all respects, and that any and all revisions required by the final examining committee have been made. Co-Chairs of the Supervisory Committee: ___________________________________________________________ Bernard Hallet ___________________________________________________________ David R. Montgomery Reading Committee: ____________________________________________________________ Bernard Hallet ____________________________________________________________ David R. Montgomery ____________________________________________________________ Gerard Roe Date:________________________ In presenting this dissertation in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the doctoral degree at the University of Washington, I agree that the Library shall make its copies freely available for inspection. I further agree that extensive copying of the dissertation is allowable only for scholarly purposes, consistent with “fair use” as prescribed in the U.S. Copyright Law. Requests for copying or reproduction of this dissertation may be referred -

Asian Alpine E-News Issue No.54

ASIAN ALPINE E-NEWS Issue No. 54 August 2019 Contents Journey through south Yushu of Qinghai Province, eastern Tibet Nangqen to Mekong Headwaters, July 2019 Tamotsu (Tom) Nakamura Part 1 Buddhists’ Kingdom-Monasteries, rock peaks, blue poppies Page 2~16 Part 2 From Mekong Headwaters to upper Yangtze River. Page 17~32 1 Journey through south Yushu of Qinghai Province, eastern Tibet Nangqen to Mekong Headwaters, July 2019 Tamotsu (Tom) Nakamura Part 1 Buddhists’ Kingdom – Monasteries, rock peaks, blue poppies “Yushu used to be a strategic point of Qinghai, explorers’ crossroads and killing field of frontier.” Geography and Climate of Yushu With an elevation of around 3,700 metres (12,100 ft), Yushu has an alpine subarctic climate, with long, cold, very dry winters, and short, rainy, and mild summers. Average low temperatures are below freezing from early/mid October to late April; however, due to the wide diurnal temperature variation, the average high never lowers to the freezing mark. Despite frequent rain during summer, when a majority of days sees rain, only June, the rainiest month, has less than 50% of possible sunshine; with monthly percent possible sunshine ranging from 49% in June to 66% in November, the city receives 2,496 hours of bright sunshine annually. The monthly 24-hour average temperature ranges from −7.6 °C (18.3 °F) in January to 12.7 °C (54.9 °F) in July, while the annual mean is 3.22 °C (37.8 °F). About three-fourths of the annual precipitation of 486 mm (19.1 in) is delivered from June to September. -

Exotic Landscapes and Ethnic Frontiers China's National

Socioanthropic Studies Vol. 1 (2020) International Journal of Cross-Cultural Studies, 1(1) : 17-30 © Serials Publications EXOTIC LANDSCAPES AND ETHNIC FRONTIERS CHINA’S NATIONAL MINORITIES ON FILM Karsten Krueger This paper presents a seldom known chapter within the general history of Chinese documentary film: the early history of ethnographic film in the People’s Republic of China between 1957 and 1966 - prior to the outbreak of the so-called “Cultural Revolution”. Taking as example the films on the Oroqen, Mosuo and other Non-Han-Chinese ethnic groups–films which were produced during the late 1950s and early 1960s as part of a wider National project–the pre-1966 ethnic identification campaigns-this paper-by way of contextualizing the historical and political background of these early Chinese Ethnographic films, discusses the strategies of filmic representation of the ethnic Other and strategies of ethnographic authentification which are specific for these very early examples of ethnographic documentary film in China. Keywords: China. Ethnographic Film. National Minorities. Authenticity. History of Documentary Film. Introduction Visual media (including ethnographic film) are now an integral part of the canon of ethnographic studies and social and cultural analyses. The American anthropologist Karl Heider (1991) showed in his study of Indonesian cinema how the Indonesian state authorities have used film to help create national consciousness in their multi- ethnic state. In the age of satellite television and affordable video cameras, visual media have become new instruments for forging identity. The same phenomenon holds true for China as for Indonesia. The current political leaders are well aware of the influence of visual media in creating a national identity. -

THE SECURITISATION of TIBETAN BUDDHISM in COMMUNIST CHINA Abstract

ПОЛИТИКОЛОГИЈА РЕЛИГИЈЕ бр. 2/2012 год VI • POLITICS AND RELIGION • POLITOLOGIE DES RELIGIONS • Nº 2/2012 Vol. VI ___________________________________________________________________________ Tsering Topgyal 1 Прегледни рад Royal Holloway University of London UDK: 243.4:323(510)”1949/...” United Kingdom THE SECURITISATION OF TIBETAN BUDDHISM IN COMMUNIST CHINA Abstract This article examines the troubled relationship between Tibetan Buddhism and the Chinese state since 1949. In the history of this relationship, a cyclical pattern of Chinese attempts, both violently assimilative and subtly corrosive, to control Tibetan Buddhism and a multifaceted Tibetan resistance to defend their religious heritage, will be revealed. This article will develop a security-based logic for that cyclical dynamic. For these purposes, a two-level analytical framework will be applied. First, the framework of the insecurity dilemma will be used to draw the broad outlines of the historical cycles of repression and resistance. However, the insecurity dilemma does not look inside the concept of security and it is not helpful to establish how Tibetan Buddhism became a security issue in the first place and continues to retain that status. The theory of securitisation is best suited to perform this analytical task. As such, the cycles of Chinese repression and Tibetan resistance fundamentally originate from the incessant securitisation of Tibetan Buddhism by the Chinese state and its apparatchiks. The paper also considers the why, how, and who of this securitisation, setting the stage for a future research project taking up the analytical effort to study the why, how and who of a potential desecuritisation of all things Tibetan, including Tibetan Buddhism, and its benefits for resolving the protracted Sino- Tibetan conflict. -

TIBET - NEPAL Septembre - Octobre 2021

VOYAGE PEKIN - TIBET - NEPAL Septembre - octobre 2021 VOYAGE PEKIN - TIBET - NEPAL Itinéraire de 21 jours Genève - Zurich - Beijing - train - Lhasa - Gyantse - Shigatse - Shelkar - Camp de base de l’Everest - Gyirong - Kathmandu - Parc National de Chitwan - Kathmandu - Delhi - Zurich - Genève ITINERAIRE EN UN CLIN D’ŒIL 1 15.09.2021 Vol Suisse - Beijing 2 16.09.2021 Arrivée à Beijing 3 17.09.2021 Beijing 4 18.09.2021 Beijing 5 19.09.2021 Beijing - Train de Pékin vers le Tibet 6 20.09.2021 Train 7 21.09.2021 Arrivée à Lhassa 8 22.09.2021 Lhassa 9 23.09.2021 Lhassa 10 24.09.2021 Lhassa - Lac Yamdrok - Gyantse 11 25.09.2021 Gyantse - Shigatse 12 26.09.2021 Shigatse - Shelkar 13 27.09.2021 Shelkar - Rongbuk - Camp de base de l'Everest 14 28.09.2021 Rongbuk - Gyirong 15 29.09.2021 Gyirong – Rasuwa - Kathmandou 16 30.09.2021 Kathmandou 17 01.10.2021 Kathmandou - Parc national de Chitwan 18 02.10.2021 Parc national de Chitwan 19 03.10.2021 Parc national de Chitwan - Kathmandou 20 04.10.2021 Vol Kathmandou - Delhi - Suisse 21 05.10.2021 Arrivée en Suisse Itinéraire Tibet googlemap de Lhassa à Gyirong : https://goo.gl/maps/RN7H1SVXeqnHpXDP6 Itinéraire Népal googlemap de Rasuwa au Parc National de Chitwan : https://goo.gl/maps/eZLHs3ACJQQsAW7J7 ITINERAIRE DETAILLE : Jour 1 / 2 : VOL GENEVE – ZURICH (OU SIMILAIRE) - BEIJING Enregistrement de vos bagages au moins 2h00 avant l’envol à l’un des guichets de la compagnie aérienne. Rue du Midi 11 – 1003 Lausanne +41 21 311 26 87 ou + 41 78 734 14 03 @ [email protected] Jour 2 : ARRIVEE A BEIJING A votre arrivée à Beijing, formalités d’immigration, accueil par votre guide et transfert à l’hôtel. -

Title the Kilen Language of Manchuria

The Kilen language of Manchuria: grammar of amoribund Title Tungusic language Author(s) Zhang, Paiyu.; 张派予. Citation Issue Date 2013 URL http://hdl.handle.net/10722/181880 The author retains all proprietary rights, (such as patent Rights rights) and the right to use in future works. ! ! ! THE KILEN LANGUAGE OF MANCHURIA: GRAMMAR OF A MORIBUND TUNGUSIC LANGUAGE ZHANG PAIYU Ph.D. THESIS UNIVERSITY OF HONG KONG February 2013 Abstract of thesis entitled The Kilen Language of Manchuria: Grammar of a moribund Tungusic language Submitted by Zhang Paiyu For the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at The University of Hong Kong in February 2013 This thesis is the first comprehensive reference grammar of Kilen, a lesser known and little studied language of the Tungusic Family. At present, Kilen is a moribund language with less than 10 bilingual speakers in the eastern part of Heilongjiang Province of P.R.China. Since the language does not have a writing system, the examples are provided in IPA transcription with morpheme tagging. This thesis is divided into eight chapters. Chapter 1 states the background information of Kilen language in terms of Ethnology, Migration and Language Contact. Beginning from Chapter 2, the language is described in the aspects of Phonology, Morphology and Syntax. This thesis is mainly concerned with morphosyntactic aspects of Kilen. Chapters 6-8 provide a portrait of Kilen syntactic organization. The sources for this description include the work of You Zhixian (1989), which documents oral literature originally recorded by You himself, a fluent Kilen native speaker; example sentences drawn from previous linguistic descriptions, mainly those of An (1985) and You & Fu (1987); author’s field records and personal consultation data recorded and transcribed by the author and Wu Mingxiang, one of the last fluent native speakers. -

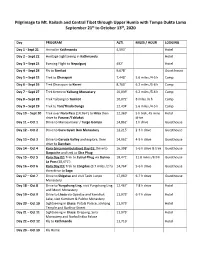

Pilgrimage to Mt. Kailash and Central Tibet Through Upper Humla with Tempa Dukte Lama September 21St to October 13Th, 2020

Pilgrimage to Mt. Kailash and Central Tibet through Upper Humla with Tempa Dukte Lama September 21st to October 13th, 2020 Day PROGRAM ALTI. MILES / HOUR LODGING Day 1 - Sept 21 Arrival in Kathmandu 4,593’ Hotel Day 2 – Sept 22 Heritage Sightseeing in Kathmandu Hotel Day 3 – Sept 23 Evening Flight to Nepalgunj 492’ Hotel Day 4 – Sept 24 Fly to Simikot 9,678’ Guest house Day 5 – Sept 25 Trek to Dharapari 7,448’ 5.6 miles /4-5 h Camp Day 6 – Sept 26 Trek Dharapori to Kermi 8,760’ 6.2 miles /5-6 h Camp Day 7 – Sept 27 Trek Kermi to Yalbang Monastery 10,039’ 6.2 miles /5-6 h Camp Day 8 – Sept 28 Trek Yalbang to Tumkot 10,072’ 8 miles /6 h Camp Day 9 – Sept 29 Trek to Yari/Thado Dunga 12,434’ 5.6 miles /4-5 h Camp Day 10 – Sept 30 Trek over Nara Pass (14,764’) to Hilsa then 12,369’ 5 h trek, 45 mins Hotel drive to Purang /Taklakot drive Day 11 – Oct 1 Drive to Manasarowar / Turgo Gompa 14,862’ 1 h drive Guesthouse Day 12 – Oct 2 Drive to Guru Gyam Bon Monastery 12,215’ 2-3 h drive Guesthouse Day 13 – Oct 3 Drive to Garuda Valley and explore, then 14,961’ 4-5 h drive Guesthouse drive to Darchen Day 14 – Oct 4 Kora (circumambulation) Day 01: Drive to 16,398’ 5-6 h drive & trek Guesthouse Darpoche and trek to Dira Phug Day 15 – Oct 5 Kora Day 02: Trek to Zutrul Phug via Dolma 18,471’ 11.8 miles /8-9 h Guesthouse La Pass (18,471’) Day 16 – Oct 6 Kora Day 03: Trek to Zongdue (3.7 miles /2 h) 14,764’ 5-6 h drive Guesthouse then drive to Saga Day 17 – Oct 7 Drive to Shigatse and visit Tashi Lunpo 17,060’ 6-7 h drive Guesthouse Monastery Day 18 – Oct 8 Drive to Yungdrung Ling, visit Yungdrung Ling 12,467’ 7-8 h drive Hotel and Menri Monastery Day 19 – Oct 9 Drive to Lhasa via Gyantse and Yamdrok 11,975’ 6-7 h drive Hotel Lake, visit Kumbum & Palcho Monastery Day 20 – Oct 10 Sightseeing in Lhasa: Potala Palace, Jokhang 11,975’ Hotel Temple and Barkhor Street Day 21 – Oct 11 Sightseeing in Lhasa: Drepung, Sera 11,975’ Hotel Monastery and Norbulinkha Palace Day 22 – Oct 12 Fly to Kathmandu 11,716’ Hotel Day 23 – Oct 13 Fly Home . -

“Little Tibet” with “Little Mecca”: Religion, Ethnicity and Social Change on the Sino-Tibetan Borderland (China)

“LITTLE TIBET” WITH “LITTLE MECCA”: RELIGION, ETHNICITY AND SOCIAL CHANGE ON THE SINO-TIBETAN BORDERLAND (CHINA) A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Cornell University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Yinong Zhang August 2009 © 2009 Yinong Zhang “LITTLE TIBET” WITH “LITTLE MECCA”: RELIGION, ETHNICITY AND SOCIAL CHANGE ON THE SINO-TIBETAN BORDERLAND (CHINA) Yinong Zhang, Ph. D. Cornell University 2009 This dissertation examines the complexity of religious and ethnic diversity in the context of contemporary China. Based on my two years of ethnographic fieldwork in Taktsang Lhamo (Ch: Langmusi) of southern Gansu province, I investigate the ethnic and religious revival since the Chinese political relaxation in the 1980s in two local communities: one is the salient Tibetan Buddhist revival represented by the rebuilding of the local monastery, the revitalization of religious and folk ceremonies, and the rising attention from the tourists; the other is the almost invisible Islamic revival among the Chinese Muslims (Hui) who have inhabited in this Tibetan land for centuries. Distinctive when compared to their Tibetan counterpart, the most noticeable phenomenon in the local Hui revival is a revitalization of Hui entrepreneurship, which is represented by the dominant Hui restaurants, shops, hotels, and bus lines. As I show in my dissertation both the Tibetan monastic ceremonies and Hui entrepreneurship are the intrinsic part of local ethnoreligious revival. Moreover these seemingly unrelated phenomena are in fact closely related and reflect the modern Chinese nation-building as well as the influences from an increasingly globalized and government directed Chinese market. -

Tibet: Psychology of Happiness and Well-Being

Psychology 410 Psychology of Well-Being and Happiness Syllabus: Psychology 410, Summer 2020 Psychology of Happiness and Well-Being Course Content: The goal of this course is to understand and experience teachings on happiness and well-being that come from psychological science and from Buddhism (particularly Tibetan Buddhism), through an intercultural learning experience in Tibet. Through being immersed in authentic Tibetan community and culture, students will be able to have an anchored learning experience of the teachings of Tibetan Buddhism and compare this with their studies about the psychological science of well-being and happiness. Belief in Buddhism or any other religion is not necessary for the course. The cultural experiences in Tibet and understanding the teachings of Buddhism give one assemblage point upon which to compare and contrast multiple views of happiness and well-being. Particular attention is given in this course to understanding the concept of anxiety management from a psychological science and Buddhist viewpoint, as the management of anxiety has a very strong effect on well- being. Textbook (Required Readings): The course uses open source readings and videos that can be accessed through the PSU Library proxies, and open source websites. Instructors and Program Support Course Instructors and Program Support: Christopher Allen, Ph.D. and Norzom Lala, MSW candidate. Christopher and Norzom are married partners. ChristopherPsyc is an adjunct faculty member and senior instructor in the department of psychology at PSU. He has won the John Eliot Alan award for outstanding teacher at PSU in 2015 and 2019. His area of expertise includes personality and well- being psychology, and a special interest in mindfulness practices. -

On Professors' Academic Power in Universities

Vol 4. No. 2 June 2009 Journal of Cambridge Studies 67 The Star-shaped Towers of the Tribal Corridor of Southwest China Frederique DARRAGON∗ Unicorn Heritage Institute, Sichuan University ABSTRACT: Hundreds of free-standing tall towering stone structures, some of the most astonishing star shapes, are still standing, in the remote, earthquake prone, mountains of Western Sichuan and Southeastern Tibet, part of a region also called Kham. I had stumbled by coincidence upon them, but I later learned that no one knew who had built them, or why, or when. After 11 years of research, hampered by the lack of local written language, and after sending 68 samples of wood, collected from their now broken beams, for carbon-dating, I was able to establish that the towers still standing were built from 200 AD to 1600 AD, they must have been thousands, and they span over a territory large as a third of France. I was also able to determine that, in fact, they belong to 4 different groups, each located in a specific geographical pocket that corresponds to the traditional lands of an ancient tribe. The towers, standing between at 1500 to 4000 meters above sea level, have shapes, masonry techniques and architectural characteristics that are unique to this region and, also, contrary to most other extraordinary towering buildings in the world, they are lay and vernacular constructions. These flamboyant towers are architectural masterpieces and outstanding examples of traditional human settlement and land use which deserve a UNESCO inscription under everyone of the 7 criteria. It is our common responsibility to make known and protect such glorious heritage.