Kanji – Not All Greek to Me

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Display of Japanese Language Features Within Ecoa Measures

Display of Japanese Language Features within eCOA Measures: Challenges and Recommendations Authors: Jonathan Norman, BA (Hons); Naoto Hasegawa, BA; Matthew Blackall, BA; Alisa Heinzman, MFA; Tim Poepsel, PhD; Rachna Kaul, MPA; Brittanie Newton, BA; Elizabeth McCullough, MA; Shawn McKown, MA OBJECTIVE DISCUSSION According to the World Health Organisation, after the US and China, Japan is home to the third highest number of clinical trials in the Kanji appearing with Chinese strokes rather than Japanese strokes (which RWS Life Sciences found to be the case in 57% of our world1. In fact, the number of trials being conducted in Japan increased by over 6,000% from 2001 (n=83) to 2017 (n=5,305). As a result convenience sample) is often caused by Chinese and Japanese eCOA builds being programmed to use the same font. Where a character of this, the use of Japanese Clinical Outcome Assessments (COAs) has become increasingly commonplace. The objective of this study only appears in Japanese, the system displays the character correctly as there is no other option. However, where a character appears was to describe and analyse two of the main challenges associated with the display of Japanese language features in electronic COAs in both Japanese and Chinese (as is the case with Kanji), some fonts will use the Chinese version only meaning that the character displays (eCOAs) and present recommendations for their resolution. incorrectly for Japan. Although Kanji characters displayed using Chinese strokes are understandable to a Japanese-speaking audience, it’s important to BACKGROUND remember how a COA is interpreted can impact the way certain respondents will interact with it. -

JLPT Explanatory Notes on the Use of the Flashcards.Pdf

Explanatory Notes on the Use of the Flashcards General Introduction There are four sets of flashcards—Grammar, Kana, Kanji and Vocabulary flashcards. In the current digital age, it might seem superfluous to have printable, paper flashcards as there are now plenty of resources online to learn and review Japanese with. However, they can be very useful for a variety of reasons. First of all, physical flashcards have one primary purpose: to help you learn something. That might sound strange, but haven’t you ever switched on your phone to study some vocabulary on your favorite app only to get distracted by some social media notification. The next thing you know, you’ve spent 30 minutes checking up on your friend’s social life and haven’t learned anything new. That’s why using a single-purpose tool like paper flashcards can be a huge help. It helps you to stay focused and sometimes that is the most difficult part of studying a new language. The second reason is that paper flashcards don’t require any electricity. You can use them anytime, anywhere in any environment without worrying about a system crash or your battery dying. Use these flashcards to review what you’ve learned from the Study Guide so that you are fully equipped with the necessary language skills, before going into the test. There is a big difference between being familiar with something and knowing it well. The JLPT expects you to know the material and recall it quickly. That means frequent revision and practice. 1. Grammar Flashcards – Quick Start Guide The grammar cards contain the key phrases from all the grammar units of the Study Guide. -

Writing As Aesthetic in Modern and Contemporary Japanese-Language Literature

At the Intersection of Script and Literature: Writing as Aesthetic in Modern and Contemporary Japanese-language Literature Christopher J Lowy A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Washington 2021 Reading Committee: Edward Mack, Chair Davinder Bhowmik Zev Handel Jeffrey Todd Knight Program Authorized to Offer Degree: Asian Languages and Literature ©Copyright 2021 Christopher J Lowy University of Washington Abstract At the Intersection of Script and Literature: Writing as Aesthetic in Modern and Contemporary Japanese-language Literature Christopher J Lowy Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Edward Mack Department of Asian Languages and Literature This dissertation examines the dynamic relationship between written language and literary fiction in modern and contemporary Japanese-language literature. I analyze how script and narration come together to function as a site of expression, and how they connect to questions of visuality, textuality, and materiality. Informed by work from the field of textual humanities, my project brings together new philological approaches to visual aspects of text in literature written in the Japanese script. Because research in English on the visual textuality of Japanese-language literature is scant, my work serves as a fundamental first-step in creating a new area of critical interest by establishing key terms and a general theoretical framework from which to approach the topic. Chapter One establishes the scope of my project and the vocabulary necessary for an analysis of script relative to narrative content; Chapter Two looks at one author’s relationship with written language; and Chapters Three and Four apply the concepts explored in Chapter One to a variety of modern and contemporary literary texts where script plays a central role. -

Chinese, Dutch, and Japanese in the Introduction of Western Learning in Tokugawa Japan

_full_alt_author_running_head (neem stramien B2 voor dit chapter en dubbelklik nul hierna en zet 2 auteursnamen neer op die plek met and): 0 _full_articletitle_deel (kopregel rechts, vul hierna in): Polyglot Translators _full_article_language: en indien anders: engelse articletitle: 0 62 Heijdra Chapter 6 Polyglot Translators: Chinese, Dutch, and Japanese in the Introduction of Western Learning in Tokugawa Japan Martin J. Heijdra The life of an area studies librarian is not always excitement. Yes, one enjoys informing bright graduate students of the latest scholarship, identifying Chi- nese rubbings of Egyptological stelae, or discussing publishing gaps in the cur- rent scholarship with knowledgeable editors; but it involves sometimes the mundane, such as reshelving a copy of a nineteenth-century Japanese transla- tion of a medical work by Johannes de Gorter.1 It was while performing the latter duty that I noticed something odd. The characters used to write Gorter were 我爾德兒, which indeed could be read as Gorter. That is, if read in modern Chinese; if read in the usual Sino-Japanese, it would be *Gajitokuji, something far from the Dutch pronunciation. A quick perusal of some scholars of rangaku 蘭學, “Dutch Studies,” revealed a general lack of awareness of this question, why a Dutch name in a nineteenth-century Japanese book would be read in modern Chinese. Prompted to write an article in honor of a Dutch editor of East and South Asian Studies, I decided to inves- tigate this more thoroughly. There are many aspects to consider, and I must confess that the final reason is hard to come by; but while I have not reached a final conclusion, I hope that in the future scholars will at least recognize the phenomenon when encountered. -

Print This Article

Reviews | 159 Germany, Rewohlt Verlag established a paperback series called “New Women” and, from 1977 to 1995, introduced many women writers’ texts, not only from German-language communities but also other nations. In the 1980s, the largest publisher in Germany, Suhrkamp, asked Hijiya- Kirschnereit to become the editor of a 32-volume series on Japanese literature. This meant rapidly increasing interest in Japanese literature in Germany in the 1980s. In 1990, at the world-famous Frankfurt Book Fair, Japan was selected as the country of theme. Along with Hijiya-Kirschnereit’s translation projects came changes in the book market, general readership, and studies of Japanese women’s literature in the German-language community. As discussed above, Hijiya-Kirschnereit’s focus is on publications and studies on women’s literature in German- and Japanese-language communities. Her 2018 volume reviewed here complements Joan E. Ericson’s careful analysis in her Be a Woman: Hayashi Fumiko and Modern Japanese Women’s Literature (University of Hawai‘i Press, 1997), which pointed out that the literary category joryū bungaku associated sentimentality, lyricism, and impressionism with works of literature written by women, erasing individual differences in women and in each work of literature by the same author. Read in conjunction with Ericson’s analysis, Hijiya-Kirschnereit’s volume helps us understand the personal and literary history of individual authors, the development of the publishing industry, general and academic readership, and studies of modern Japanese women’s literature in the Japanese-, German-, and English-language communities. Japanese Kanji Power: A Workbook for Mastering Japanese Characters By John Millen. -

Title Japanese Kanji Learning Method for Arabic Speakers Sub

Title Japanese Kanji learning method for Arabic speakers Sub Title Author Alsharif, Afnan(Katō, Akira) 加藤, 朗 Publisher 慶應義塾大学大学院メディアデザイン研究科 Publication year 2017 Jtitle Abstract Notes Genre Thesis or Dissertation URL http://koara.lib.keio.ac.jp/xoonips/modules/xoonips/detail.php?koara_id=KO40001001-00002017 -0564 Powered by TCPDF (www.tcpdf.org) Master's thesis Academic Year 2017 Japanese Kanji Learning Method for Arabic Speakers Keio University Graduate School of Media Design Alsharif Afnan A Master’s Thesis submitted to Keio University Graduate School of Media Design in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER of Media Design Alsharif Afnan Thesis Committee: Professor Akira Kato (Supervisor) Professor Hideki Sunahara (Co-Supervisor) Senior Assistant Professor Marcos Sadao Maekawa (Reviewer) Abstract of Master’s Thesis of Academic Year 2017 Japanese Kanji Learning Method for Arabic Speakers Category: Design Summary Arabic speakers who wish to learn Japanese deal with a very limited number of Kanji resources. This is because for several centuries the cultural exchange between Japan and the Arab world has been inactive which reflected on the amount of published work between the two nations. Learners mostly rely on English resources but this is not an efficient way to learn because first, not every Arabic speaker knows English and second, during translation meaning lost can happen. We address this challenging problem by proposing a learning method specific to native Arabic speakers. It employs two ideas: The first is Arabic Kanji Equivalent which is a copied version of Kanji in Arabic words. The second is Phrase Based Learning where Japanese text along with Arabic translation is given for active reading practice. -

Rubric for Script (Adapted from VAC

Rubric for Script (adapted from VAC http://www.carla.umn.edu/assessment/VAC/evaluation/e_1.html) Mechanics (3 points possible) Score 1st Draft 3 Few errors in punctuation and mastery of writing in genkoo yooshi (special format for Japanese composition). Hiragana and Katakana are written carefully with few errors. 2 Frequent errors in punctuation and lack of mastery of writing in genkoo yooshi. Hiragana and Katakana are written with frequent errors and demonstrate poor writing skills. 1 Dominated by errors in punctuation, in writing of Hiragana and Katakana, and no mastery of writing in genkoo yooshi. Content (4 points possible) Score Final 4 Topic clearly and fully developed. Details, descriptions, examples, and anecdotes explain and clarify information. All task requirements more than adequately fulfilled. 3 Topic adequately developed with relevant information and some details. Task requirements adequately fulfilled. 2 Topic partially developed; some relevant information is missing; few or no details. Task requirements partially fulfilled. 1 Topic poorly developed and/or task requirements not fulfilled. Or not enough material to evaluate. Grammar (5 points possible) Score Final 5 Few grammatical mistakes and the meaning is always clear. 4 Occasional grammatical mistakes, but do not interfere with the meaning of the message. 3 Frequent grammatical mistakes and sometimes interfere with the meaning of the message. 2 Very frequent grammatical mistakes and often interfere with the meaning of the message. 1 Incomprehensible or not enough material provided to evaluate. Vocabulary (4 points possible) Score Final 4 Wide range of vocabulary learned in class, used appropriately in all instances and with few spelling mistakes. -

A Content Analysis of Kanji Textbooks Targeted for Second Language Learners of Japanese

STOCKHOLMS UNIVERSITY Department of Asian, Middle Eastern and Turkish Studies A Content Analysis of Kanji Textbooks Targeted for Second Language Learners of Japanese Master of Art Thesis 2015 Joonas Riekkinen Supervisor: Gunnar Linder Acknowledgements There are several people that in many ways have contributed to make this thesis possible, but I will only acknowledge some of them. First I need to thank my supervisor Gunnar “Jinmei” Linder who in a short notice decided to undertake this project. He has in many ways inspired me over the years. I would also like to thank the staff, teachers and lecturers that I had over the years at Stockholm University. I also wish to thank the kanji teachers that I had at Tohoku University. Many thanks to Dennis “BAMF” Moberg for inspiring me, for introducing me various methods of kanji learning and for making countless of kanji word lists. I am looking forward for our future collaboration. Thanks to Jasmine “Master of the Universe” Öjbro for countless of corrections and proofreading. Thanks to Admir “Deus” Hodzic for proofreading, despite the fact of not knowing any Japanese. I also wish to thank Carlos “Akki” Giotis, for making it easy for me to combine monotonous studies with work. I want to thank my mother Marja Riekkinen for supporting me for many years. Last, I would like to thank Narumi Chiba for the help I received in Japan, as well as in the early stages of my master studies. 1 Introduction 1 1.1 Terminology 2 1.2 Purpose and Research Question 3 1.3 Theoretical Framework 4 1.3.1 Kanji and its -

Robust Segmentation of Japanese Text Into a Lattice for Parsing

Robust Segmentation of Japanese Text into a Lattice for Parsing Gary Kacmarcik, Chris Brockett, Hisami Suzuki Microsoft Research One Microsoft Way Redmond WA, 98052 USA {garykac,chrisbkt,hisamis}@microsoft.com of records for a given input string. This is Abstract typically done using a connective-cost model We describe a segmentation component that ([Hisamitsu90]), which is either maintained utilizes minimal syntactic knowledge to produce a laboriously by hand, or trained on large corpora. lattice of word candidates for a broad coverage Japanese NL parser. The segmenter is a finite Both of these approaches suffer from problems. state morphological analyzer and text normalizer Handcrafted heuristics may become a maintenance designed to handle the orthographic variations quagmire, and as [Kurohashi98] suggests in his characteristic of written Japanese, including discussion of the JUMAN segmenter, statistical alternate spellings, script variation, vowel models may become increasingly fragile as the extensions and word-internal parenthetical system grows and eventually reach a point where material. This architecture differs from con- side effects rule out further improvements. The ventional Japanese wordbreakers in that it does sparse data problem commonly encountered in not attempt to simultaneously attack the problems of identifying segmentation candidates and statistical methods is exacerbated in Japanese by choosing the most probable analysis. To minimize widespread orthographic variation (see §3). duplication of effort between components and to Our system addresses these pitfalls by assigning give the segmenter greater freedom to address completely separate roles to the segmenter and the orthography issues, the task of choosing the best parser to allow each to delve deeper into the analysis is handled by the parser, which has access to a much richer set of linguistic information. -

General Explanations Nihon Kokugo Daijiten Editorial Policy 1

General Explanations Nihon kokugo daijiten Editorial Policy 1. This dictionary attempts to offer a historical account of the meanings and usages of the Japanese language through reference to various written materials. 2. Entry items include the vocabulary of modern Japanese as well as items from historical texts. Proper nouns, including names of places and people, and technical and specialized terms are also included. 3. Definitions of a given word are generally arranged in historical order; usage citations are accompanied by the name of the text in which they appear. 4. Sources for citations are taken from a broad spectrum of texts including literary, historical, religious, and other works of various periods. 5. Citation sources range from works of antiquity to works of the Meiji, Taishō, and Shōwa periods. Chinese texts are also used for Sino-Japanese words. 6. Citations are taken from the most reliable versions of historical texts; in cases where variant texts are cited, notice is given. 7. Identification of citations is a specific as possible. In order to facilitate comprehension, some citations include the author's name and the field with which the text is associated. 8. Separate subheadings for Dialectal Variants, Etymology, Pronunciation, and Premodern Dictionary Citations are included with commentary where appropriate. 9. Entry headings and definitions are based on modern standards, and are intended to make location and comprehension as easy as possible. Components of the Descriptions The descriptions of words in this dictionary are composed of the following elements: entry heading, historical kana orthography, kanji, part of speech, definitions, examples and sources, supplementary notes, dialectal variants, etymology, pronunciation, and premodern dictionary citations. -

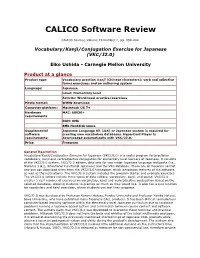

CALICO Software Review

CALICO Software Review CALICO Journal, Volume 19 Number 2, pp. 390-404 Vocabulary/Kanji/Conjugation Exercise for Japanese (VKC/J2.0) Eiko Ushida - Carnegie Mellon University Product at a glance Product type: Vocabulary practice; kanji (Chinese characters); verb and adjective forms exercises; and an authoring system Language: Japanese Level: Elementary level Activity: Word-level practice/exercises Media format: WWW download Computer platform: Macintosh OS 7+ Hardware MAC: 68030+ requirements RAM: 8Mb 8Mb Harddisk space Supplemental Japanese Language Kit (JLK) or Japanese system is required for software creating own vocabulary databases. HyperCard Player is requirements: downloaded automatically with VKC/J2.0. Price: Freeware General Description Vocabulary/Kanji/Conjugation Exercise for Japanese (VKC/J2.0) is a useful program for practicing vocabulary, kanji and verb/adjective conjugation for elementary level learners of Japanese. It consists of the VKC/J2.0 system, VKC/J2.0 editors, data sets for two major Japanese language textbooks (i.e., Nakama 1 & 2, Situational Functional Japanese) and the VKC database. These are all freeware so that any one can download them from the VKC/J2.0 homepage, which introduces features of the software as well as the instructions. The VKC/J2.0 system includes the program starter and example exercises. The VKC/J2.0 editors include three types of data editors; vocabulary, kanji, and sound. VKC/J2.0 creates a vast number of exercises on vocabulary, kanji and verb/adjective conjugation based on the selected database, allowing students to practice as much as they would like. It also has a quiz function for vocabulary and kanji exercises, where students can test their progress. -

The ALA-LC Japanese Romanization Table

Japanese The ALA-LC Japanese Romanization Table Revision Proposal March 30, 2018 Created by CTP/CJM Joint Working Group on the ALA-LC Japanese Romanization Table (JRTWG) JRTWG is part of: Association of Asian Studies (AAS) Council on East Asian Libraries (CEAL) Committee on Technical Processing (CTP) and Committee on Japanese Materials (CJM) JRTWG Co-Chairs: Yukari Sugiyama (Yale University) Chiharu Watsky (Princeton University) Members of JRTWG: Rob Britt (University of Washington) Ryuta Komaki (Washington University) Fabiano Rocha (University of Toronto) Chiaki Sakai (The Japan Foundation Japanese-Language Institute, Urawa) Keiko Suzuki (The New School) [Served as Co-Chair from April to September 2016] Koji Takeuchi (Library of Congress) Table of Contents Romanization Table…………………………………………………………………………………….Pages 1-28 1. Introduction……………………………………………………………………………………Page 1 2. Basic Principles for Romanization……………………………………………………Page 1 3. Capitalization………………………………………………………………………………….Page 5 4. Japanese Punctuation and Typographical Marks…………………………….Page 8 5. Diacritic Marks and Other Symbols Used in Romanization………………Page 9 6. Word Division………………………………………………………………………………….Page 11 7. Numerals…………………………………………………………………………………………Page 25 Romanized/Kana Equivalent Charts…………………………………………………..…..…….Pages 29-30 Helpful References…………………………………………………………………………………....…Page 31 Last Updated: 3/30/2018 10:48 AM 1 Introduction: Scope of the Romanization Table Romanization is one type of transliteration. Transliteration is the process of converting text written