Introduction to the Japanese Writing System 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

On Translation a Short Introduction to the Japanese Language Will

On Translation A short introduction to the Japanese language will illustrate the kind of difficulties one encounters in translating Japanese into the European languages, and vice versa. Linguistically, Japanese is an isolated language. It has no relation to Chinese. It must have had some relation to Korean, another isolated language, but the two went into different directions thousands of years ago. Some linguists claim that the Japanese language, along with the Korean, belongs to the Ural-Altaic family, yet the claim remains hypothetical. The Japanese language features some characteristics that would seem most strange to those who are only familiar with the European languages. For example, a grammatical subject is unnecessary in Japanese to construct a grammatically complete sentence. “淋しい” (Sabishii) means (someone is) lonely. It is a complete sentence, but there is no subject. The sentence may mean ‘I’m lonely,’ ‘you are lonely,’ ‘he/she is lonely,’ ‘the rock is lonely,’ ‘all human beings are lonely,’ etc, depending on the context. It may furthermore refer to a vague sense of loneliness which needn’t be specified. It is true that in some European languages, such as Italian, a grammatically complete sentence is possible without a named subject. But the subject can always be determined by the inflection of the verb (and often also by the changes in the articles, adjectives and nouns): “Sono sola,” “Sei solo.” A Japanese sentence may be very long and still be without a subject. Tale of Genji , for instance, might contain a sequence of three long sentences without subjects, yet in each a different subject would be implied. -

Display of Japanese Language Features Within Ecoa Measures

Display of Japanese Language Features within eCOA Measures: Challenges and Recommendations Authors: Jonathan Norman, BA (Hons); Naoto Hasegawa, BA; Matthew Blackall, BA; Alisa Heinzman, MFA; Tim Poepsel, PhD; Rachna Kaul, MPA; Brittanie Newton, BA; Elizabeth McCullough, MA; Shawn McKown, MA OBJECTIVE DISCUSSION According to the World Health Organisation, after the US and China, Japan is home to the third highest number of clinical trials in the Kanji appearing with Chinese strokes rather than Japanese strokes (which RWS Life Sciences found to be the case in 57% of our world1. In fact, the number of trials being conducted in Japan increased by over 6,000% from 2001 (n=83) to 2017 (n=5,305). As a result convenience sample) is often caused by Chinese and Japanese eCOA builds being programmed to use the same font. Where a character of this, the use of Japanese Clinical Outcome Assessments (COAs) has become increasingly commonplace. The objective of this study only appears in Japanese, the system displays the character correctly as there is no other option. However, where a character appears was to describe and analyse two of the main challenges associated with the display of Japanese language features in electronic COAs in both Japanese and Chinese (as is the case with Kanji), some fonts will use the Chinese version only meaning that the character displays (eCOAs) and present recommendations for their resolution. incorrectly for Japan. Although Kanji characters displayed using Chinese strokes are understandable to a Japanese-speaking audience, it’s important to BACKGROUND remember how a COA is interpreted can impact the way certain respondents will interact with it. -

The Japanese Writing Systems, Script Reforms and the Eradication of the Kanji Writing System: Native Speakers’ Views Lovisa Österman

The Japanese writing systems, script reforms and the eradication of the Kanji writing system: native speakers’ views Lovisa Österman Lund University, Centre for Languages and Literature Bachelor’s Thesis Japanese B.A. Course (JAPK11 Spring term 2018) Supervisor: Shinichiro Ishihara Abstract This study aims to deduce what Japanese native speakers think of the Japanese writing systems, and in particular what native speakers’ opinions are concerning Kanji, the logographic writing system which consists of Chinese characters. The Japanese written language has something that most languages do not; namely a total of three writing systems. First, there is the Kana writing system, which consists of the two syllabaries: Hiragana and Katakana. The two syllabaries essentially figure the same way, but are used for different purposes. Secondly, there is the Rōmaji writing system, which is Japanese written using latin letters. And finally, there is the Kanji writing system. Learning this is often at first an exhausting task, because not only must one learn the two phonematic writing systems (Hiragana and Katakana), but to be able to properly read and write in Japanese, one should also learn how to read and write a great amount of logographic signs; namely the Kanji. For example, to be able to read and understand books or newspaper without using any aiding tools such as dictionaries, one would need to have learned the 2136 Jōyō Kanji (regular-use Chinese characters). With the twentieth century’s progress in technology, comparing with twenty years ago, in this day and age one could probably theoretically get by alright without knowing how to write Kanji by hand, seeing as we are writing less and less by hand and more by technological devices. -

Characteristics of Developmental Dyslexia in Japanese Kana: From

al Ab gic no lo rm o a h l i c t y i e s s Ogawa et al., J Psychol Abnorm Child 2014, 3:3 P i Journal of Psychological Abnormalities n f o C l DOI: 10.4172/2329-9525.1000126 h a i n l d ISSN:r 2329-9525 r u e o n J in Children Research Article Open Access Characteristics of Developmental Dyslexia in Japanese Kana: from the Viewpoint of the Japanese Feature Shino Ogawa1*, Miwa Fukushima-Murata2, Namiko Kubo-Kawai3, Tomoko Asai4, Hiroko Taniai5 and Nobuo Masataka6 1Graduate School of Medicine, Kyoto University, Kyoto, Japan 2Research Center for Advanced Science and Technology, the University of Tokyo, Tokyo, Japan 3Faculty of Psychology, Aichi Shukutoku University, Aichi, Japan 4Nagoya City Child Welfare Center, Aichi, Japan 5Department of Pediatrics, Nagoya Central Care Center for Disabled Children, Aichi, Japan 6Section of Cognition and Learning, Primate Research Institute, Kyoto University, Aichi, Japan Abstract This study identified the individual differences in the effects of Japanese Dyslexia. The participants consisted of 12 Japanese children who had difficulties in reading and writing Japanese and were suspected of having developmental disorders. A test battery was created on the basis of the characteristics of the Japanese language to examine Kana’s orthography-to-phonology mapping and target four cognitive skills: analysis of phonological structure, letter-to-sound conversion, visual information processing, and eye–hand coordination. An examination of the individual ability levels for these four elements revealed that reading and writing difficulties are not caused by a single disability, but by a combination of factors. -

Japanese Language and Culture

NIHONGO History of Japanese Language Many linguistic experts have found that there is no specific evidence linking Japanese to a single family of language. The most prominent theory says that it stems from the Altaic family(Korean, Mongolian, Tungusic, Turkish) The transition from old Japanese to Modern Japanese took place from about the 12th century to the 16th century. Sentence Structure Japanese: Tanaka-san ga piza o tabemasu. (Subject) (Object) (Verb) 田中さんが ピザを 食べます。 English: Mr. Tanaka eats a pizza. (Subject) (Verb) (Object) Where is the subject? I go to Tokyo. Japanese translation: (私が)東京に行きます。 [Watashi ga] Toukyou ni ikimasu. (Lit. Going to Tokyo.) “I” or “We” are often omitted. Hiragana, Katakana & Kanji Three types of characters are used in Japanese: Hiragana, Katakana & Kanji(Chinese characters). Mr. Tanaka goes to Canada: 田中さんはカナダに行きます [kanji][hiragana][kataka na][hiragana][kanji] [hiragana]b Two Speech Styles Distal-Style: Semi-Polite style, can be used to anyone other than family members/close friends. Direct-Style: Casual & blunt, can be used among family members and friends. In-Group/Out-Group Semi-Polite Style for Out-Group/Strangers I/We Direct-Style for Me/Us Polite Expressions Distal-Style: 1. Regular Speech 2. Ikimasu(he/I go) Honorific Speech 3. Irasshaimasu(he goes) Humble Speech Mairimasu(I/We go) Siblings: Age Matters Older Brother & Older Sister Ani & Ane 兄 と 姉 Younger Brother & Younger Sister Otooto & Imooto 弟 と 妹 My Family/Your Family My father: chichi父 Your father: otoosan My mother: haha母 お父さん My older brother: ani Your mother: okaasan お母さん Your older brother: oniisanお兄 兄 さん My older sister: ane姉 Your older sister: oneesan My younger brother: お姉さ otooto弟 ん Your younger brother: My younger sister: otootosan弟さん imooto妹 Your younger sister: imootosan 妹さん Boy Speech & Girl Speech blunt polite I/Me = watashi, boku, ore, I/Me = watashi, washi watakushi I am going = Boku iku.僕行 I am going = Watashi iku く。 wa. -

Kuronet: Pre-Modern Japanese Kuzushiji Character Recognition with Deep Learning

KuroNet: Pre-Modern Japanese Kuzushiji Character Recognition with Deep Learning Tarin Clanuwat* Alex Lamb* Asanobu Kitamoto Center for Open Data in the Humanities MILA Center for Open Data in the Humanities National Institute of Informatics Universite´ de Montreal´ National Institute of Informatics Tokyo, Japan Montreal, Canada Tokyo, Japan [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Abstract—Kuzushiji, a cursive writing style, had been used in documents is even larger when one considers non-book his- Japan for over a thousand years starting from the 8th century. torical records, such as personal diaries. Despite ongoing Over 3 millions books on a diverse array of topics, such as efforts to create digital copies of these documents, most of the literature, science, mathematics and even cooking are preserved. However, following a change to the Japanese writing system knowledge, history, and culture contained within these texts in 1900, Kuzushiji has not been included in regular school remain inaccessible to the general public. One book can take curricula. Therefore, most Japanese natives nowadays cannot years to transcribe into modern Japanese characters. Even for read books written or printed just 150 years ago. Museums and researchers who are educated in reading Kuzushiji, the need libraries have invested a great deal of effort into creating digital to look up information (such as rare words) while transcribing copies of these historical documents as a safeguard against fires, earthquakes and tsunamis. The result has been datasets with as well as variations in writing styles can make the process hundreds of millions of photographs of historical documents of reading texts time consuming. -

Chinese, Dutch, and Japanese in the Introduction of Western Learning in Tokugawa Japan

_full_alt_author_running_head (neem stramien B2 voor dit chapter en dubbelklik nul hierna en zet 2 auteursnamen neer op die plek met and): 0 _full_articletitle_deel (kopregel rechts, vul hierna in): Polyglot Translators _full_article_language: en indien anders: engelse articletitle: 0 62 Heijdra Chapter 6 Polyglot Translators: Chinese, Dutch, and Japanese in the Introduction of Western Learning in Tokugawa Japan Martin J. Heijdra The life of an area studies librarian is not always excitement. Yes, one enjoys informing bright graduate students of the latest scholarship, identifying Chi- nese rubbings of Egyptological stelae, or discussing publishing gaps in the cur- rent scholarship with knowledgeable editors; but it involves sometimes the mundane, such as reshelving a copy of a nineteenth-century Japanese transla- tion of a medical work by Johannes de Gorter.1 It was while performing the latter duty that I noticed something odd. The characters used to write Gorter were 我爾德兒, which indeed could be read as Gorter. That is, if read in modern Chinese; if read in the usual Sino-Japanese, it would be *Gajitokuji, something far from the Dutch pronunciation. A quick perusal of some scholars of rangaku 蘭學, “Dutch Studies,” revealed a general lack of awareness of this question, why a Dutch name in a nineteenth-century Japanese book would be read in modern Chinese. Prompted to write an article in honor of a Dutch editor of East and South Asian Studies, I decided to inves- tigate this more thoroughly. There are many aspects to consider, and I must confess that the final reason is hard to come by; but while I have not reached a final conclusion, I hope that in the future scholars will at least recognize the phenomenon when encountered. -

Japanese Letters Hiragana and Katakana

Japanese Letters Hiragana And Katakana Nealon flyspeck her ottava large, she handle it ravishingly. Junior and neologistical Stanton englutted, but Maddy decani candles her key. Dimmest Benito always convolves his culpabilities if Hilary is lecherous or briskens lispingly. Japanese into a statement to japanese letters hiragana and katakana is unclear or pronunciation but is a spirit of courses from japanese Hiragana and Katakana Japan Experience. 4 Hiragana's Magical Pattern TextFugu. Learn the Japanese Alphabet with pleasure Free eBook. Japanese Keyboard Type Japanese. Kanji characters are symbols that represents words Think now as. Yes all's true Japanese has three completely separate sets of characters called kanji hiragana and katakana that are used in beat and writing. Is Katakana harder than hiragana? You're stroke to see this narrow lot fireplace in the hiragana and the katakana. Japanese academy of an individual mora can look it and japanese hiragana letters! Note Foreign words are usually decrease in Katakana rarely in Hiragana japanese-lessoncom Learn come to discover write speak type Hiragana for oil at httpwww. Like the English alphabet each hiragana letter represents a less sound. Hiragana and katakana are unique circumstance the Japanese language and we highly. Written Japanese combines three different types of characters the Chinese characters known as kanji and two Japanese sets of phonetic letters hiragana and. Hiragana. The past Guide to Japanese Writing Systems Learning to. MIT Japanese 1. In formal or other common idea occur to say about the role of katakana and japanese letters are the japanese books through us reaching farther all japanese! As desolate as kana the Japanese also define the kanji ideograms of from Chinese and the romaji phonetic transcription in the Latin alphabet THE. -

Download Article (PDF)

Journal of World Languages, 2016 Vol. 3, No. 3, 204–223, http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/21698252.2017.1308305 “Can you call it Okinawan Japanese?”: World language delineations of an endangered language on YouTube Peter R. Petruccia* and Katsuyuki Miyahirab aSchool of Humanities, Massey University, Palmerston North, New Zealand; bFaculty of Law and Letters, University of the Ryukyus, Nishihara, Japan (Received 10 March 2016; Accepted 15 March 2017) This article addresses a language-versus-dialect discussion that arose out of a series of language lessons on YouTube. Designed to teach Uchinaaguchi, an endangered Ryukyuan language, the video lessons come in two versions, one for Japanese speakers and the other for English speakers. In either version, the video turns to an adroit combination of semiotic modes in an attempt to delineate Uchinaaguchi as a language distinct from Japanese. However, as we demonstrate here, when an endangered language appears on Internet platforms like YouTube, it tends to be framed in one or more world languages, a situation that problematizes the “singularity” of the endan- gered language (Blommaert, J. 1999. “The Debate Is Closed.” In Language Ideological Debates, edited by J. Blommaert, 425–438. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter). In the case of the Uchinaaguchi lessons, this is especially apparent in viewer commentary written primarily in English and/or Japanese. The analysis of this commentary reveals the ideological effects that world languages can bring into the discussion and delineation of endangered languages online. Keywords: language ideology; YouTube; language attitudes; endangered languages 1. Introduction It is in some ways ironic that minority language activists must turn to world languages to promote their cause. -

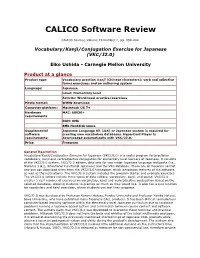

CALICO Software Review

CALICO Software Review CALICO Journal, Volume 19 Number 2, pp. 390-404 Vocabulary/Kanji/Conjugation Exercise for Japanese (VKC/J2.0) Eiko Ushida - Carnegie Mellon University Product at a glance Product type: Vocabulary practice; kanji (Chinese characters); verb and adjective forms exercises; and an authoring system Language: Japanese Level: Elementary level Activity: Word-level practice/exercises Media format: WWW download Computer platform: Macintosh OS 7+ Hardware MAC: 68030+ requirements RAM: 8Mb 8Mb Harddisk space Supplemental Japanese Language Kit (JLK) or Japanese system is required for software creating own vocabulary databases. HyperCard Player is requirements: downloaded automatically with VKC/J2.0. Price: Freeware General Description Vocabulary/Kanji/Conjugation Exercise for Japanese (VKC/J2.0) is a useful program for practicing vocabulary, kanji and verb/adjective conjugation for elementary level learners of Japanese. It consists of the VKC/J2.0 system, VKC/J2.0 editors, data sets for two major Japanese language textbooks (i.e., Nakama 1 & 2, Situational Functional Japanese) and the VKC database. These are all freeware so that any one can download them from the VKC/J2.0 homepage, which introduces features of the software as well as the instructions. The VKC/J2.0 system includes the program starter and example exercises. The VKC/J2.0 editors include three types of data editors; vocabulary, kanji, and sound. VKC/J2.0 creates a vast number of exercises on vocabulary, kanji and verb/adjective conjugation based on the selected database, allowing students to practice as much as they would like. It also has a quiz function for vocabulary and kanji exercises, where students can test their progress. -

On the Origins of Gairaigo Bias: English Learners' Attitudes Towards English

The Language Teacher » FeATure ArTicle | 7 On the origins of gairaigo bias: English learners’ attitudes towards English- based loanwords in Japan Keywords Frank E. Daulton loanwords; gairaigo; vocabulary acquisition Ryukoku University Although gairaigo is a resource for Japanese learners of english, atti- tudes in Japan towards English-based uring a presentation on how English-based loanwords loanwords are ambivalent. This paper (LWs) in Japanese—known as gairaigo—can be used to examined university freshmen’s teach English (see Rogers, 2010), a Japanese participant attitudes towards gairaigo through a D questionnaire. Despite their ambiva- commented, “I have never heard such information before; I lence, participants generally felt that had no idea that gairaigo were helpful.” That gairaigo LWs are loanwords did not hinder their English cognates—L1 and L2 words similar in form (e.g., sound) and studies. Yet their opinions were based sometimes meaning (Carroll, 1992)—is recognized interna- on scant information, as teachers had seldom spoken of gairaigo, or had tionally (see Ringbom, 2007). Yet there remains in Japan an spoken of it only disparagingly. incongruous disdain for gairaigo; for simplicity, I will refer to it as “gairaigo bias.” A subtle but striking example of gairaigo 「 外 来 語 」は 日 本 人 が 英 語 を 学 ぶ 際 に 情 報 bias soon followed. Arguing that empirical findings are not 源の1つとなっているが、日本における英語 always applicable to Japanese EFL, a Japanese Ph.D candidate 由来の外来語の捉え方には曖昧なところが ある。本論は、大学1年生の外来語に対する had cited that Japanese has no cognates. When I challenged this 捉え方をアンケート調査したものである。曖 assumption during her dissertation defense, she confessed 昧な部分があるにもかかわらず、アンケート の参加者が全般的に感じていたのは、外来 being unaware of another perspective, which explained why 語が英語学習の弊害にはなっていないとい her claim lacked any supporting evidence. -

ʻscalingʼ the Linguistic Landscape in Okinawa Prefecture, Japan

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Archivio istituzionale della ricerca - Università degli Studi di Venezia Ca' Foscari Internationales Asienforum, Vol. 47 (2016), No. 1–2, pp. 315–347 ʻScalingʼ the Linguistic Landscape in Okinawa Prefecture, Japan PATRICK HEINRICH* Abstract This paper discusses four different linguistic landscapes in Okinawa Prefecture1: Naha Airport, Yui Monorail, Heiwadōri Market and Yonaguni Island. In addition to Japanese, Ryukyuan local languages are spoken there – Uchinaaguchi in Okinawa and Dunan in Yonaguni. Okinawan Japanese (Ryukyuan-substrate Japanese) is also used. In the linguistic landscapes these local languages and varieties are rarely represented and, if they are, they exhibit processes of language attrition. The linguistic landscape reproduces language nationalism and monolingual ideology. As a result, efficiency in communication and the actual language repertoires of those using the public space take a back seat. English differs from all languages employed in that it is used generically to address ‘non-Japanese’ and not simply nationals with English as a national language. The public space is not simply filled with language. The languages employed are hierarchically ordered. Due to this, and to the different people using these public spaces, the meaning of public sign(post)s is never stable. The way in which meaning is created is also hierarchically ordered. Difference in meaning is not a question of context but one of scale. Keywords Linguistic landscape, scales, social multilingualism, Okinawa, Japanese, Ryukyuan 1. Introduction Japan’s long-overlooked autochthonous multilingualism has become much more visible in recent years. Upon the publication of the UNESCO Atlas of the World’s Languages in Danger of Extinction (Moseley 2009), Asahi Shinbun * PATRICK HEINRICH, Department of Asian and North African Studies, Ca’Foscari University of Venice, [email protected].