Chinese, Dutch, and Japanese in the Introduction of Western Learning in Tokugawa Japan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Stochastic Model of Stroke Order Variation

2009 10th International Conference on Document Analysis and Recognition Stochastic Model of Stroke Order Variation Yoshinori Katayama, Seiichi Uchida, and Hiroaki Sakoe Faculty of Information Science and Electrical Engineering, Kyushu University, 819-0395, Japan fyosinori,[email protected] Abstract “ ¡ ” under an unnatural stroke correspondence which max- imizes their similarity. Note that the correct stroke order of A stochastic model of stroke order variation is proposed “ ” is (“—” ! “j' ! “=” ! “n” ! “–”) and that of “ ¡ ” and applied to the stroke-order free on-line Kanji character is (“—” ! “–” ! “j' ! “=” ! “n” ). Thus if we allow any recognition. The proposed model is a hidden Markov model stroke order variation, those two characters become almost (HMM) with a special topology to represent all stroke order identical. variations. A sequence of state transitions from the initial One possible remedy to suppress the misrecognitions is state to the final state of the model represents one stroke to penalize unnatural i.e., rare stroke order on optimizing order and provides a probability of the stroke order. The the stroke correspondence. In fact, there are popular stroke distribution of the stroke order probability can be trained orders (including the standard stroke order) and there are automatically by using an EM algorithm from a training rare stroke orders. If we penalize the situation that “ ¡ ” is set of on-line character patterns. Experimental results on matched to an input pattern with its very rare stroke order large-scale test patterns showed that the proposed model of (“—” ! “j' ! “=” ! “n” ! “–”), we can avoid the could represent actual stroke order variations appropriately misrecognition of “ ” as “ ¡ .” and improve recognition accuracy by penalizing incorrect For this purpose, a stochastic model of stroke order vari- stroke orders. -

Nushu and the Writing of Religious

NOSHU AND RELIGIOUS CULTURE IN CHINA "MY MOTHER WATCHED OVER AN EMPTY HOUSE AND',WAS SEPARATED FROM THE HEA VENL Y FEMALE": NUSHU AND THE WRITING OF RELIGIOUS CULTURE IN CHINA By STEPHANIE BALK WILL, B.A. (H.Hons.) A Thesis Submitted to the School of Graduate Studies in Partial FulfiHment ofthe Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts McMaster University © Copyright by Stephanie Balkwill, August 2006 MASTER OF ARTS (2006) McMaster University (Religious Studies) Hamilton, Ontario TITLE: "My Mother Watched Over an Empty House and was Separated From the Heavenly Female": Nushu and the Writing IOf Religious Culture in China. AUTHOR: Stephanie Balkwill, B.A. (H.Hons.) (University of Regina) SUPERVISOR: Dr. James Benn NUMBER OF PAGES: v, 120 ii ]rll[.' ' ABSTRACT Niishu, or "Women's Script" is a system of writing indigenous to a small group of village women in iJiangyong County, Hunan Province, China. Used exclusively by and for these women, the script was developed in order to write down their oral traditions that may have included songs, prayers, stories and biographies. However, since being discovered by Chinese and Western researchers, nushu has been rapidly brought out of this Chinese village locale. At present, the script has become an object of fascination for diverse audiences all over the world. It has been both the topic of popular media presentations and publications as well as the topic of major academic research projects published in Engli$h, German, Chinese and Japanese. Resultantly, niishu has played host to a number of mo~ern explanations and interpretations - all of which attempt to explain I the "how" and the "why" of an exclusively female script developed by supposedly illiterate women. -

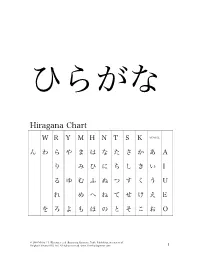

Hiragana Chart

ひらがな Hiragana Chart W R Y M H N T S K VOWEL ん わ ら や ま は な た さ か あ A り み ひ に ち し き い I る ゆ む ふ ぬ つ す く う U れ め へ ね て せ け え E を ろ よ も ほ の と そ こ お O © 2010 Michael L. Kluemper et al. Beginning Japanese, Tuttle Publishing, an imprint of Periplus Editions (HK) Ltd. All rights reserved. www.TimeForJapanese.com. 1 Beginning Japanese 名前: ________________________ 1-1 Hiragana Activity Book 日付: ___月 ___日 一、 Practice: あいうえお かきくけこ がぎぐげご O E U I A お え う い あ あ お え う い あ お う あ え い あ お え う い お う い あ お え あ KO KE KU KI KA こ け く き か か こ け く き か こ け く く き か か こ き き か こ こ け か け く く き き こ け か © 2010 Michael L. Kluemper et al. Beginning Japanese, Tuttle Publishing, an imprint of Periplus Editions (HK) Ltd. All rights reserved. www.TimeForJapanese.com. 2 GO GE GU GI GA ご げ ぐ ぎ が が ご げ ぐ ぎ が ご ご げ ぐ ぐ ぎ ぎ が が ご げ ぎ が ご ご げ が げ ぐ ぐ ぎ ぎ ご げ が 二、 Fill in each blank with the correct HIRAGANA. SE N SE I KI A RA NA MA E 1. -

Display of Japanese Language Features Within Ecoa Measures

Display of Japanese Language Features within eCOA Measures: Challenges and Recommendations Authors: Jonathan Norman, BA (Hons); Naoto Hasegawa, BA; Matthew Blackall, BA; Alisa Heinzman, MFA; Tim Poepsel, PhD; Rachna Kaul, MPA; Brittanie Newton, BA; Elizabeth McCullough, MA; Shawn McKown, MA OBJECTIVE DISCUSSION According to the World Health Organisation, after the US and China, Japan is home to the third highest number of clinical trials in the Kanji appearing with Chinese strokes rather than Japanese strokes (which RWS Life Sciences found to be the case in 57% of our world1. In fact, the number of trials being conducted in Japan increased by over 6,000% from 2001 (n=83) to 2017 (n=5,305). As a result convenience sample) is often caused by Chinese and Japanese eCOA builds being programmed to use the same font. Where a character of this, the use of Japanese Clinical Outcome Assessments (COAs) has become increasingly commonplace. The objective of this study only appears in Japanese, the system displays the character correctly as there is no other option. However, where a character appears was to describe and analyse two of the main challenges associated with the display of Japanese language features in electronic COAs in both Japanese and Chinese (as is the case with Kanji), some fonts will use the Chinese version only meaning that the character displays (eCOAs) and present recommendations for their resolution. incorrectly for Japan. Although Kanji characters displayed using Chinese strokes are understandable to a Japanese-speaking audience, it’s important to BACKGROUND remember how a COA is interpreted can impact the way certain respondents will interact with it. -

Handy Katakana Workbook.Pdf

First Edition HANDY KATAKANA WORKBOOK An Introduction to Japanese Writing: KANA THIS IS A SUPPLEMENT FOR BEGINNING LEVEL JAPANESE LANGUAGE INSTRUCTION. \ FrF!' '---~---- , - Y. M. Shimazu, Ed.D. -----~---- TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Introduction vi ACKNOWLEDGEMENlS vii STUDYSHEET#l 1 A,I,U,E, 0, KA,I<I, KU,KE, KO, GA,GI,GU,GE,GO, N WORKSHEET #1 2 PRACTICE: A, I,U, E, 0, KA,KI, KU,KE, KO, GA,GI,GU, GE,GO, N WORKSHEET #2 3 MORE PRACTICE: A, I, U, E,0, KA,KI,KU, KE, KO, GA,GI,GU,GE,GO, N WORKSHEET #~3 4 ADDmONAL PRACTICE: A,I,U, E,0, KA,KI, KU,KE, KO, GA,GI,GU,GE,GO, N STUDYSHEET #2 5 SA,SHI,SU,SE, SO, ZA,JI,ZU,ZE,ZO, TA, CHI, TSU, TE,TO, DA, DE,DO WORI<SHEEI' #4 6 PRACTICE: SA,SHI,SU,SE, SO, ZA,II, ZU,ZE,ZO, TA, CHI, 'lSU,TE,TO, OA, DE,DO WORI<SHEEI' #5 7 MORE PRACTICE: SA,SHI,SU,SE,SO, ZA,II, ZU,ZE, W, TA, CHI, TSU, TE,TO, DA, DE,DO WORKSHEET #6 8 ADDmONAL PRACI'ICE: SA,SHI,SU,SE, SO, ZA,JI, ZU,ZE,ZO, TA, CHI,TSU,TE,TO, DA, DE,DO STUDYSHEET #3 9 NA,NI, NU,NE,NO, HA, HI,FU,HE, HO, BA, BI,BU,BE,BO, PA, PI,PU,PE,PO WORKSHEET #7 10 PRACTICE: NA,NI, NU, NE,NO, HA, HI,FU,HE,HO, BA,BI, BU,BE, BO, PA, PI,PU,PE,PO WORKSHEET #8 11 MORE PRACTICE: NA,NI, NU,NE,NO, HA,HI, FU,HE, HO, BA,BI,BU,BE, BO, PA,PI,PU,PE,PO WORKSHEET #9 12 ADDmONAL PRACTICE: NA,NI, NU, NE,NO, HA, HI, FU,HE, HO, BA,BI,3U, BE, BO, PA, PI,PU,PE,PO STUDYSHEET #4 13 MA, MI,MU, ME, MO, YA, W, YO WORKSHEET#10 14 PRACTICE: MA,MI, MU,ME, MO, YA, W, YO WORKSHEET #11 15 MORE PRACTICE: MA, MI,MU,ME,MO, YA, W, YO WORKSHEET #12 16 ADDmONAL PRACTICE: MA,MI,MU, ME, MO, YA, W, YO STUDYSHEET #5 17 -

Chinese Script Generation Panel Document

Chinese Script Generation Panel Document Proposal for the Generation Panel for the Chinese Script Label Generation Ruleset for the Root Zone 1. General Information Chinese script is the logograms used in the writing of Chinese and some other Asian languages. They are called Hanzi in Chinese, Kanji in Japanese and Hanja in Korean. Since the Hanzi unification in the Qin dynasty (221-207 B.C.), the most important change in the Chinese Hanzi occurred in the middle of the 20th century when more than two thousand Simplified characters were introduced as official forms in Mainland China. As a result, the Chinese language has two writing systems: Simplified Chinese (SC) and Traditional Chinese (TC). Both systems are expressed using different subsets under the Unicode definition of the same Han script. The two writing systems use SC and TC respectively while sharing a large common “unchanged” Hanzi subset that occupies around 60% in contemporary use. The common “unchanged” Hanzi subset enables a simplified Chinese user to understand texts written in traditional Chinese with little difficulty and vice versa. The Hanzi in SC and TC have the same meaning and the same pronunciation and are typical variants. The Japanese kanji were adopted for recording the Japanese language from the 5th century AD. Chinese words borrowed into Japanese could be written with Chinese characters, while Japanese words could be written using the character for a Chinese word of similar meaning. Finally, in Japanese, all three scripts (kanji, and the hiragana and katakana syllabaries) are used as main scripts. The Chinese script spread to Korea together with Buddhism from the 2nd century BC to the 5th century AD. -

A Comparative Analysis of the Simplification of Chinese Characters in Japan and China

CONTRASTING APPROACHES TO CHINESE CHARACTER REFORM: A COMPARATIVE ANALYSIS OF THE SIMPLIFICATION OF CHINESE CHARACTERS IN JAPAN AND CHINA A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE DIVISION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF HAWAI‘I AT MĀNOA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS IN ASIAN STUDIES AUGUST 2012 By Kei Imafuku Thesis Committee: Alexander Vovin, Chairperson Robert Huey Dina Rudolph Yoshimi ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to express deep gratitude to Alexander Vovin, Robert Huey, and Dina R. Yoshimi for their Japanese and Chinese expertise and kind encouragement throughout the writing of this thesis. Their guidance, as well as the support of the Center for Japanese Studies, School of Pacific and Asian Studies, and the East-West Center, has been invaluable. i ABSTRACT Due to the complexity and number of Chinese characters used in Chinese and Japanese, some characters were the target of simplification reforms. However, Japanese and Chinese simplifications frequently differed, resulting in the existence of multiple forms of the same character being used in different places. This study investigates the differences between the Japanese and Chinese simplifications and the effects of the simplification techniques implemented by each side. The more conservative Japanese simplifications were achieved by instating simpler historical character variants while the more radical Chinese simplifications were achieved primarily through the use of whole cursive script forms and phonetic simplification techniques. These techniques, however, have been criticized for their detrimental effects on character recognition, semantic and phonetic clarity, and consistency – issues less present with the Japanese approach. By comparing the Japanese and Chinese simplification techniques, this study seeks to determine the characteristics of more effective, less controversial Chinese character simplifications. -

Writing As Aesthetic in Modern and Contemporary Japanese-Language Literature

At the Intersection of Script and Literature: Writing as Aesthetic in Modern and Contemporary Japanese-language Literature Christopher J Lowy A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Washington 2021 Reading Committee: Edward Mack, Chair Davinder Bhowmik Zev Handel Jeffrey Todd Knight Program Authorized to Offer Degree: Asian Languages and Literature ©Copyright 2021 Christopher J Lowy University of Washington Abstract At the Intersection of Script and Literature: Writing as Aesthetic in Modern and Contemporary Japanese-language Literature Christopher J Lowy Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Edward Mack Department of Asian Languages and Literature This dissertation examines the dynamic relationship between written language and literary fiction in modern and contemporary Japanese-language literature. I analyze how script and narration come together to function as a site of expression, and how they connect to questions of visuality, textuality, and materiality. Informed by work from the field of textual humanities, my project brings together new philological approaches to visual aspects of text in literature written in the Japanese script. Because research in English on the visual textuality of Japanese-language literature is scant, my work serves as a fundamental first-step in creating a new area of critical interest by establishing key terms and a general theoretical framework from which to approach the topic. Chapter One establishes the scope of my project and the vocabulary necessary for an analysis of script relative to narrative content; Chapter Two looks at one author’s relationship with written language; and Chapters Three and Four apply the concepts explored in Chapter One to a variety of modern and contemporary literary texts where script plays a central role. -

Frank's Do-It-Yourself Kana Cards V

Frank's do-it-yourself kana cards v. 1.0, 2000-08-07 Frank Stajano University of Cambridge and AT&T Laboratories Cambridge http://www.cl.cam.ac.uk/~fms27/ and http://www.uk.research.att.com/~fms/ This set of flash cards is meant to help you familiar cards and insist on the difficult part of き and さ with a separate stroke, become fluent in the use of the Japanese ones. unlike what happens in the fonts used in hiragana and katakana syllabaries. I made this document. I have followed the stroke it because I needed one myself and could The complete set consists of 10 double- counts of Henshall-Takagaki, even when not find it in the local bookshops (kanji sided sheets (20 printable pages) of 50 they seem weird for the shape of the char- cards were available, and I bought those; cards each, but you may choose to print acter as drawn on the card. but kana cards weren't); if it helps you too, smaller subsets as detailed below. Actu- so much the better. ally there are some blanks, so the total The easiest way to turn this document into number of cards is only 428 instead of 500. a set of cards is simply to print it (double The romanisation system chosen for these It would have been possible to fit them on sided of course!) and then cut each page cards is the Hepburn, which is the most 9 sheets instead of 10, but only by com- into cards with a ruler and a sharp blade. -

The Perception of Simplified and Traditional Chinese Characters in the Eye of Simplified and Traditional Chinese Readers

The perception of simplified and traditional Chinese characters in the eye of simplified and traditional Chinese readers Tianyin Liu ([email protected]) Janet Hui-wen Hsiao ([email protected]) Department of Psychology, University of Hong Kong 604 Knowles Building, Pokfulam Road, Hong Kong SAR Abstract components and have better ability to ignore some unimportant configural information for recognition, such as Expertise in Chinese character recognition is marked by analytic/reduced holistic processing (Hsiao & Cottrell, 2009), exact distances between features (Ge, Wang, McCleery, & which depends mainly on readers’ writing rather than reading Lee, 2006) compared with novices (Ho, Ng, & Ng., 2003; experience (Tso, Au, & Hsiao, 2011). Here we examined Hsiao & Cottrell, 2009). Consequently, expert readers may whether simplified and traditional Chinese readers process process Chinese characters less holistically than novices. characters differently in terms of holistic processing. When There are currently two Chinese writing systems in use processing characters that are distinctive in the simplified and in Chinese speaking regions, namely simplified and traditional scripts, we found that simplified Chinese readers were more analytic than traditional Chinese readers in traditional Chinese. The simplified script was created during perceiving simplified characters; this effect depended on their the writing reform initiated by the central government of the writing rather than reading/copying performance. In contrast, People’s Republic of China in the 1960s for easing the the two groups did not differ in holistic processing of learning process. Today the majority of Chinese speaking traditional characters, regardless of their performance regions including Mainland China, Singapore, and Malaysia difference in writing/reading traditional characters. -

Old Scripts, New Actors: European Encounters with Chinese Writing, 1550-1700 *

EASTM 26 (2007): 68-116 Old Scripts, New Actors: European Encounters with Chinese Writing, 1550-1700 * Bruce Rusk [Bruce Rusk is Assistant Professor of Chinese Literature in the Department of Asian Studies at Cornell University. From 2004 to 2006 he was Mellon Humani- ties Fellow in the Asian Languages Department at Stanford University. His dis- sertation was entitled “The Rogue Classicist: Feng Fang and his Forgeries” (UCLA, 2004) and his article “Not Written in Stone: Ming Readers of the Great Learning and the Impact of Forgery” appeared in The Harvard Journal of Asi- atic Studies 66.1 (June 2006).] * * * But if a savage or a moon-man came And found a page, a furrowed runic field, And curiously studied line and frame: How strange would be the world that they revealed. A magic gallery of oddities. He would see A and B as man and beast, As moving tongues or arms or legs or eyes, Now slow, now rushing, all constraint released, Like prints of ravens’ feet upon the snow. — Herman Hesse 1 Visitors to the Far East from early modern Europe reported many marvels, among them a writing system unlike any familiar alphabetic script. That the in- habitants of Cathay “in a single character make several letters that comprise one * My thanks to all those who provided feedback on previous versions of this paper, especially the workshop commentator, Anthony Grafton, and Liam Brockey, Benjamin Elman, and Martin Heijdra as well as to the Humanities Fellows at Stanford. I thank the two anonymous readers, whose thoughtful comments were invaluable in the revision of this essay. -

Female Fabrications: an Examination of the Public and Private Aspects of Nüshu

FEMALE FABRICATIONS: AN EXAMINATION OF THE PUBLIC AND PRIVATE ASPECTS OF NÜSHU Ann-Gee Lee A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY December 2008 Committee: Sue Carter Wood, Advisor Jaclyn Cuneen Graduate Faculty Representative Kristine L. Blair Richard Gebhardt ii © 2008 Ann-Gee Lee All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Sue Carter Wood, Advisor Nüshu is a Chinese women's script believed to have been invented and used before the Cultural Revolution. For about a couple centuries, Nüshu was used by uneducated rural women in Jiangyong County, Hunan Province, in China to communicate and correspond with one another, cope with their hardships, and promote creativity. Its complexity lies in the fact that it may come in different forms: written on paper fans or silk-bound books; embroidered on clothing and accessories; or sung while a woman or group of women were doing their domestic work. Although Nüshu is an old and somewhat secret female language which has been used for over 100 years, it has only been an academic field of study for about 25 years. Further, in the field of rhetoric and composition, despite the enormous interest in women's rhetorics and material culture, sources on Nüshu in relation to the two fields are scarce. In relation to Nüshu, through examinations of American domestic arts, such as quilts, scrapbooking, and so on, material rhetoric is slowly becoming a significant field of study. Elaine Hedges explains, “Recent research has focused on ‘ordinary women' whose household work comprised, defined, and often circumscribed their lives: the work of cooking, cleaning, and sewing that women traditionally and perpetually performed and has gone unheralded until now” (294).