029298.Pdf (157.0Kb)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Princes of Gwynedd Guidebook

Princes of Gwynedd Guidebook Discover the legends of the mighty princes of Gwynedd in the awe-inspiring landscape of North Wales PRINCES OF GWYNEDD GUIDEBOOK Front Cover: Criccieth Castle2 © Princes of Gwynedd 2013 of © Princes © Cadw, Welsh Government (Crown Copyright) This page: Dolwyddelan Castle © Conwy County Borough Council PRINCES OF GWYNEDD GUIDEBOOK 3 Dolwyddelan Castle Inside this book Step into the dramatic, historic landscapes of Wales and discover the story of the princes of Gwynedd, Wales’ most successful medieval dynasty. These remarkable leaders were formidable warriors, shrewd politicians and generous patrons of literature and architecture. Their lives and times, spanning over 900 years, have shaped the country that we know today and left an enduring mark on the modern landscape. This guidebook will show you where to find striking castles, lost palaces and peaceful churches from the age of the princes. www.snowdoniaheritage.info/princes 4 THE PRINCES OF GWYNEDD TOUR © Sarah McCarthy © Sarah Castell y Bere The princes of Gwynedd, at a glance Here are some of our top recommendations: PRINCES OF GWYNEDD GUIDEBOOK 5 Why not start your journey at the ruins of Deganwy Castle? It is poised on the twin rocky hilltops overlooking the mouth of the River Conwy, where the powerful 6th-century ruler of Gwynedd, Maelgwn ‘the Tall’, once held court. For more information, see page 15 © Princes of Gwynedd of © Princes If it’s a photo opportunity you’re after, then Criccieth Castle, a much contested fortress located high on a headland above Tremadog Bay, is a must. For more information, see page 15 © Princes of Gwynedd of © Princes If you prefer a remote, more contemplative landscape, make your way to Cymer Abbey, the Cistercian monastery where monks bred fine horses for Llywelyn ap Iorwerth, known as Llywelyn ‘the Great’. -

A Welsh Classical Dictionary

A WELSH CLASSICAL DICTIONARY DACHUN, saint of Bodmin. See s.n. Credan. He has been wrongly identified with an Irish saint Dagan in LBS II.281, 285. G.H.Doble seems to have been misled in the same way (The Saints of Cornwall, IV. 156). DAGAN or DANOG, abbot of Llancarfan. He appears as Danoc in one of the ‘Llancarfan Charters’ appended to the Life of St.Cadog (§62 in VSB p.130). Here he is a clerical witness with Sulien (presumably abbot) and king Morgan [ab Athrwys]. He appears as abbot of Llancarfan in five charters in the Book of Llandaf, where he is called Danoc abbas Carbani Uallis (BLD 179c), and Dagan(us) abbas Carbani Uallis (BLD 158, 175, 186b, 195). In these five charters he is contemporary with bishop Berthwyn and Ithel ap Morgan, king of Glywysing. He succeeded Sulien as abbot and was succeeded by Paul. See Trans.Cym., 1948 pp.291-2, (but ignore the dates), and compare Wendy Davies, LlCh p.55 where Danog and Dagan are distinguished. Wendy Davies dates the BLD charters c.A.D.722 to 740 (ibid., pp.102 - 114). DALLDAF ail CUNIN COF. (Legendary). He is included in the tale of ‘Culhwch and Olwen’ as one of the warriors of Arthur's Court: Dalldaf eil Kimin Cof (WM 460, RM 106). In a triad (TYP no.73) he is called Dalldaf eil Cunyn Cof, one of the ‘Three Peers’ of Arthur's Court. In another triad (TYP no.41) we are told that Fferlas (Grey Fetlock), the horse of Dalldaf eil Cunin Cof, was one of the ‘Three Lovers' Horses’ (or perhaps ‘Beloved Horses’). -

The North Wales Pilgrim's Way. Spiritual Re

27 The North Wales Pilgrim’s Way. Spiritual re- vival in a marginal landscape. DANIELS Andrew Abstract The 21st century has seen a marked resurgence in the popularity of pilgrim- age routes across Europe. The ‘Camino’ to Santiago de Compostela in Spain and routes in England to Walsingham in Norfolk and Canterbury in Kent are just three well-known examples where numbers of pilgrims have increased dramati- cally over the last decade. The appeal to those seeking religious as well as non- spiritual self-discovery has perhaps grown as the modern world has become ever more complicated for some. The North Wales Pilgrim’s Way is another ancient route that has once again seen a marked increase in participants during recent years. Various bodies have attempted to appropriate this spiritual landscape in or- der to attract modern pilgrims. Those undertaking the journey continue to leave their own imprints on this marginal place. Year by year they add further layers of meaning to those that have already been laid down over many centuries of pil- grimage. This short paper is the second in a series of research notes looking specifically at overlapping spiritual and tourist connections in what might be termed ‘periph- eral landscapes’ in remote coastal areas of Britain. In particular I will focus on how sites connected with early Celtic Christianity in Britain have been used over time by varying groups with different agendas. In the first paper in this series, I explored how the cult of St. Cuthbert continues to draw visitors to Lindisfarne or Holy Island in the North East of England. -

THE WAY a Review of Christian Spirituality Published by the British Jesuits

THE WAY a review of Christian spirituality published by the British Jesuits January 2003 Volume 42, Number 1 I will instruct you and teach you the way you should go. Editorial office Campion Hall, Oxford, OX1 1QS, UK Subscriptions office THE WAY, Turpin Distribution Services Ltd, Blackhorse Road, Letchworth, Hertfordshire, SG6 1HN, UK THE WAY January 2003 The Ignatian Spirituality of the Way 7 Philip Endean Ignatian sources bear witness to a spirituality of movement, of continual discovery, of ‘the way’. This converges strikingly with contemporary developments in the study of spirituality. It is from this convergence that The Way draws inspiration and energy. On Receiving an Inheritance: Confessions of a Former 22 Marginaholic James Alison James Alison’s personal story reveals much about how the marginalised are prone to self-deception, but even more about how God’s love is untouched by such manipulative behaviour. Our inheritance is assured. The Impact of Transition 34 Barbara Hendricks Whenever we try to communicate across cultural boundaries, we are ourselves drawn into a process of self-questioning, growth, and transformation. A distinguished Maryknoll missionary explores this experience. Theological Trends: Jesuit Theologies of Mission 44 Michael Sievernich Michael Sievernich explains how the idea of ‘inculturation’ was developed in Jesuit circles around the time of Vatican II, and discusses its relationship with other key notions in the contemporary theology of mission such as justice and interreligious dialogue. From the Ignatian Tradition: Guidelines for Pilgrims 58 Simão Rodrigues How early Jesuit recruits would live out the spirituality of the Exercises by going on a pilgrimage. -

Sourozh Messenger May 2017 Ascension of the Lord 13/26 May 2017

RUSSIAN ORTHODOX CHURCH DIOCESE OF SOUROZH CATHEDRAL OF THE DORMITION OF THE MOTHER OF GOD 67 ENNISMORE GARDENS, LONDON SW7 1NH Sourozh Messenger May 2017 Ascension of the Lord 13/26 May 2017 Troparion Thou art ascended in glory, O Christ our God, having filled Thy disciples with joy by the promise of the Holy Spirit; for they were assured by Thy blessing that Thou art the Son of God, the Redeemer of the world. Kontakion When Thou hadst accomplished Thy dispensation towards us, and hadst united things on earth with those in heaven, Thou didst ascend in glory, O Christ our God, in no way parted, but remaining continually with us. Thou didst cry to those who love Thee: I am with you and none shall be against you! May 2017 List of contents In this issue: IN THE footstePS OF THE Pilgrims Greetings to Archbishop Impressions of the Diocesan Anatoly.......................................................3 pilgrimage to the Holy Land DIOCESAN NEWS................................4 with the Russian Ecclesiastical Mission................................................17 Cathedral NEWS...........................5 Pilgrimage to the Holy Relics of LegacY OF MetroPolitan St Nicholas the Wonderworker ANTHONY OF Sourozh Sermon on the Feast of in Bari..................................................21 the Ascension..........................................7 HOLY Places IN LONDON BRITISH AND IRISH SAINTS St Paul’s Cathedral.............................23 Venerable Beuno, Abbot of Everlasting Art of Iconography..25 Clynnog Fawr..................................9 cathedral NEWSLETTER Notes ON THE church 30 YEARS ago calendar Metropolitan Anthony has sent Ascension of Our Lord................13 this communication Sacraments OF THE church Youth discuss faith..........................31 Part 5. Penance................................15 Recommended donation is £1 Dear Readers, We are happy to inform you that the Media and Publishing Department of the Diocese of Sourozh now has an online store, Sourozh Publications, where you can obtain the publications of the diocese. -

Then Arthur Fought the MATTER of BRITAIN 378 – 634 A.D

Then Arthur Fought THE MATTER OF BRITAIN 378 – 634 A.D. Howard M. Wiseman Then Arthur Fought is a possible history centred on a possi- bly historical figure: Arthur, battle-leader of the dark-age (5th- 6th century) Britons against the invading Anglo-Saxons. Writ- ten in the style of a medieval chronicle, its events span more than 250 years, and most of Western Europe, all the while re- specting known history. Drawing upon hundreds of ancient and medieval texts, Howard Wiseman mixes in his own inventions to forge a unique conception of Arthur and his times. Care- fully annotated, Then Arthur Fought will appeal to anyone in- terested in dark-age history and legends, or in new frameworks for Arthurian fiction. Its 430 pages include Dramatis Personae, genealogies, notes, bibliography, and 20 maps. —— Then Arthur Fought is an extraordinary achievement. ... An absorbing introduction to the history and legends of the period [and] ... a fascinating synthesis. — from the Foreword by Patrick McCormack, author of the Albion trilogy. —— A long and lavishly detailed fictional fantasia on the kind of primary source we will never have for the Age of Arthur. ... soaringly intelligent and, most unlikely of all, hugely entertaining. It is a stunning achievement, enthusiastically recommended. — Editor’s Choice review by Steve Donoghue, Indie Reviews Editor, Historical Novel Society. Contents List of Figures x Foreword, by Patrick McCormack xi Preface, by the author xv Introduction: history, literature, and this book xix Dramatis Personae xxxi Genealogies xxxix -

1 J. S. Mackley Abstract When Geoffrey of Monmouth Wrote The

English Foundation Myths as Political Empowerment J. S. Mackley University of Northampton, UK Abstract When Geoffrey of Monmouth wrote the History of the Kings of Britain in Latin around 1135-8, he claimed that he was translating an earlier source in the “British Language” and presenting a “truthful account” of British History. Geoffrey’s claims around this book gave his writing more authority, and, while this particular book has never been uncovered, he was drawing on other sources, such as Gildas, Bede and Nennius. In particular, Geoffrey elaborated a legend from Nennius that described how the first settlers of Britain were descended from Æneas and other survivors from the Trojan War. Thus, Geoffrey’s purpose was to provide a plausible ancestry for the current kings of England—Norman who had invaded only seventy years before—and to establish the nation's authority on the world stage. Keywords: Geoffrey of Monmouth; History of the Kings of Britain; English foundation mythology; Trojans; Æneas; Brutus; Corineus; Nennius; Gildas; Albion; Goemagot 1 ENGLISH FOUNDATION MYTHS AS POLITICAL EMPOWERMENT Introduction Geoffrey of Monmouth, a twelfth-century monk and teacher, is perhaps best known for being one of the earliest authors of a coherent written narrative of King Arthur and for his work on the prophecies of Merlin. His principal and innovative work, the Historia regum Britanniae (History of the Kings of Britain), presents an overview of the lives and deeds of 99 British monarchs, covering nearly 2000 years, beginning with the first settlers of the land, until the death of the last British king in 689 AD. -

Medieval and Early Post- Medieval Holy Wells

MEDIEVAL AND EARLY POST- MEDIEVAL HOLY WELLS A THREAT-RELATED ASSESSMENT 2011 Prepared by Dyfed Archaeological TrustFor For Cadw MEDIEVAL AND EARLY POST -MEDIEVAL HOLY WELLS A THREAT-RELATED ASSESSMENT 2011 DYFED ARCHAEOLOGICAL TRUST RHIF YR ADRODDIAD / REPORT NO.2012/7 RHIF Y PROSIECT / PROJECT RECORD NO. 100735 MEDIEVAL AND EARLY POST-MEDIEVAL HOLY WELLS: A THREAT-RELATED ASSESSMENT 2011 Gan / By MIKE INGS Paratowyd yr adroddiad yma at ddefnydd y cwsmer yn unig. Ni dderbynnir cyfrifoldeb gan Ymddiriedolaeth Archaeolegol Dyfed Cyf am ei ddefnyddio gan unrhyw berson na phersonau eraill a fydd yn ei ddarllen neu ddibynnu ar y gwybodaeth y mae’n ei gynnwys The report has been prepared for the specific use of the client. Dyfed Archaeological Trust Limited can accept no responsibility for its use by any other person or persons who may read it or rely on the information it contains. Ymddiriedolaeth Archaeolegol Dyfed Cyf Dyfed Archaeological Trust Limited Neuadd y Sir, Stryd Caerfyrddin, Llandeilo, Sir The Shire Hall, Carmarthen Street, Llandeilo, Gaerfyrddin SA19 6AF Carmarthenshire SA19 6AF Ffon: Ymholiadau Cyffredinol 01558 823121 Tel: General Enquiries 01558 823121 Adran Rheoli Treftadaeth 01558 823131 Heritage Management Section 01558 823131 Cwmni cyfyngedig (1198990) ynghyd ag elusen gofrestredig (504616) yw’r Ymddiriedolaeth. The Trust is both a Limited Company (No. 1198990) and a Registered Charity (No. 504616) CADEIRYDD CHAIRMAN: C R MUSSON MBE B Arch FSA MIFA. MEDIEVAL AND EARLY POST-MEDIEVAL HOLY WELLS: A THREAT-RELATED ASSESSMENT 2011 CONTENTS 1 SUMMARY 3 INTRODUCTION 4 PROJECT AIMS AND OBJECTIVES 5 METHODOLOGY 6 RESULTS 7 – 8 REFERENCES 9 GAZETTEER 10 1 2 MEDIEVAL AND EARLY POST-MEDIEVAL HOLY WELLS: A THREAT-RELATED ASSESSMENT 2011 SUMMARY The medieval and early post-medieval holy wells project forms an element of the Cadw grant-aided medieval and early post-medieval threat related assessment project. -

PAT I Ers Talwm Iawn Paganiaid Oedd Y Cymry

N TC INTO m1l PAT I Ers talwm iawn paganiaid oedd y Cymry. Roedden nhw'n addoli hen dduwiau'r Celtiaid : Cernunnos, duw'r goedwig ac anifeiliaid gwylltion (Cernunnos = carw) ; � Epona, duwies y meirch, neu Rhiannon y Mabinogion : (Epona = ebol neu eboles) ; Lieu - goleuni (enwau lleoedd fel Dinlle - Din-lieu a Nantlle - Nant-lleu) a Nudd - mae teml i'r duw hwn yn Flores! y Ddena � Epona yn Lloegr. Roedd ganddyn nhw weinidogion, gwyr doeth a elwid �I Derwyddon. Roedden nhw'n astudio natur a'r ser. Weithiau roedden nhw'n 1( aberthu gwyr a gwragedd i'r duwiau. \� � Long time ago the Welsh people were � pagans. They worshipped the old Celtic gods : Cernunnos, the god of the forest � � and wild animals (Cernunnos = deer) ; Epona, the goddess of horses, or Rhiannon from the Mabinogion : (Epona = young horse/colt) ; Lieu - light {place ' names like Dinlle CeRnannos Din-lieu and Nantlle - Nani-lieu) and Nodens - there is a _0\� '---' temple for this god in the Forest of Dean in England. They had priests, wise men called )l Druids. They I studied nature and / the stars. Sometimes they sacrificed men and women to the gods. Mae'n fwy na phosib mai ambell filwr Rhufeinig neu fasnachwr Rhufeinig ddaeth a hanes yr lesu i Gymru gyntaf oil. Most probably it was the occasional Roman soldier or a Roman merchant who first brought the story of Jesus to Wales. Au.wN't:Jl, N °'Chi Rho' YR EglWNS - The "Chi-Ro' sign Geltai�� Teml Ra.J:einig The Celtic FRNthonfg Chau.eh Gnistnogol A Romano-Buitish Cbaistian Temple ,. -

The Chronicle of the Early Britons

The Chronicle of the Early Britons - Brut y Bryttaniait - according to Jesus College MS LXI an annotated translation by Wm R Cooper MA, PhD, ThD Copyright: AD 2009 Wm R Cooper Other books by Wm R (Bill) Cooper: After the Flood (1995) Paley’s Watchmaker (1997) William Tyndale’s 1526 ew Testament (2000) British Library Wycliffe’s ew Testament 1388 (March 2002) British Library Παγε 3 Acknowledgements My thanks must go to the Principal and Fellows of Jesus College, Oxford, for their kind permission to translate Jesus College MS LXI , and to publish that translation; with special thanks to D A Rees, the archivist at the College; and to Ellis Evans, Professor of Celtic Studies at Jesus, who scrutinized the translation. Παγε 4 The Chronicle of the Early Britons Introduction There lies in an Oxford library a certain old and jaded manuscript. It is written in medieval Welsh in an informal cursive hand, and is a 15 th -century copy of a 12 th -century original (now lost). Its shelfmark today is Jesus College MS LXI , but that has not always been its name. For some considerable time it went under the far more evocative name of the Tysilio Chronicle , and early in the last century a certain archaeologist made the following observation concerning it. The year was 1917, the archaeologist was Flinders Petrie (see Bibliography), and his observation was that this manuscript was being unaccountably neglected by the scholars of his day. It was, he pointed out, perhaps the best representative of an entire group of chronicles in which are preserved certain important aspects of early British history, aspects that were not finding their way into the published notices of those whose disciplines embraced this period. -

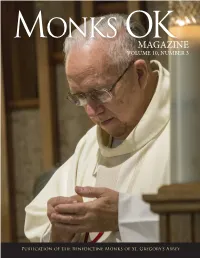

Monks Okmagazine Volume 10, Number 3

MONKS OKMAGAZINE VOLUME 10, NUMBER 3 Publication of the Benedictine Monks of St. Gregory’s Abbey Gaudete!REFLECTIONS FROM ABBOT LAWRENCE Sometimes people are or attend regional meetings without having to leave surprised when they learn the monastery. Various social media make it possible just how much monks for monks to share their faith experience with others make use of modern or to help young people discern where God is calling technologies. Access to the them. Recently, we at St. Gregory’s Abbey began to use Internet, “smart” phones, “Flocknote” to share news and reflections with Oblates tablets, fitness trackers and and friends of the Abbey. other 21st century marvels is possible for many in consecrated life – including But for all the good that new technologies bring, they monks and nuns. also can bring a dark side. All the distractions of the world can easily invade the life of a monk with the Monks and nuns often have been early adopters simple click of a mouse. Even seemingly innocent and inventors of new technologies. Medieval monks websites and a desire to keep-up with social media can developed time-keeping devices, agricultural become destructive to what should be a life of quiet techniques, architectural designs and educational reflection, prayer and work. The walls of the monastery tools. For instance, the monks of Subiaco Abbey in and a locked cloister gate are not enough to prevent Italy, founded by St. Benedict himself, installed the such invasions of the sanctuary of monastic enclosure. first printing press in Italy in the year 1464 – just 30 years after Gutenberg introduced the printing press in To prevent unhealthy distractions, communities Germany. -

The Law of Hywel

02 Elias WHR 27_7_06.qxp 09/08/2006 12:04 Page 27 LLYFR CYNOG OF CYFRAITH HYWEL AND ST CYNOG OF BRYCHEINIOG Cyfraith Hywel (the Law of Hywel) is the name given to the native Welsh law texts, written in Welsh and Latin, which are preserved in manuscripts datable to the period between c.1250 and c.1550, and originating from different parts of Wales.1 These law texts are tradition- ally attributed by their prefaces to the tenth-century king, Hywel Dda.2 Other authors or editors are also mentioned in the texts.3 Some of these were secular rulers or other laymen and some were clerics. The most well-known are Blegywryd,4 Cyfnerth and Morgenau,5 and Iorwerth ap Madog,6 to whom the main Welsh redactions, namely Llyfr Blegywryd, Llyfr Cyfnerth and Llyfr Iorwerth, are attributed. Other names, such as Rhys ap Gruffudd,7 Bleddyn ap 1 I am grateful to Morfydd E. Owen, who first suggested the possibility that the Cynog of the law tracts should be identified with St Cynog and supervised the thesis from which this article is derived. Thanks also to Huw Pryce for his biblio- graphical references, to Howard Davies for his many helpful suggestions, and Helen Davies for help with the Latin translations. For a list of the manuscripts and their sigla, see T. M. Charles-Edwards, The Welsh Laws (Cardiff, 1989), pp. 100–2. 2 J. G. Edwards, ‘Hywel Dda and the Welsh lawbooks’, in D. Jenkins (ed.), Celtic Law Papers (Brussels, 1973), pp. 135–60; H. Pryce, ‘The prologues to the Welsh lawbooks’, Bulletin of the Board of Celtic Studies, 33 (1986), 151–87.