The North Wales Pilgrim's Way. Spiritual Re

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gwynedd Bedstock Survey 2018/19 Content 1

Tourism Accommodation in Gwynedd Gwynedd Bedstock Survey 2018/19 Content 1. Introduction ................................................................................................................................... 1 2. Main Findings of the Gwynedd Tourism Accommodation Survey 2018/19 .................................. 2 3. Survey Methodology .................................................................................................................... 14 4. Analysis according to type of accommodation ............................................................................ 16 5. Analysis according to Bedrooms and Beds................................................................................... 18 6. Analysis according to Price ........................................................................................................... 21 7. Analysis according to Grade ......................................................................................................... 24 8. Comparison with previous surveys .............................................................................................. 26 9. Main Tourism Destinations .......................................................................................................... 29 10. Conclusions .................................................................................................................................. 49 Appendix 1: Visit Wales definitions of different types of accommodation .......................................... 51 Appendix 2: -

Thomas Edward Ellis Papers (GB 0210 TELLIS)

Llyfrgell Genedlaethol Cymru = The National Library of Wales Cymorth chwilio | Finding Aid - Thomas Edward Ellis Papers (GB 0210 TELLIS) Cynhyrchir gan Access to Memory (AtoM) 2.3.0 Generated by Access to Memory (AtoM) 2.3.0 Argraffwyd: Mai 04, 2017 Printed: May 04, 2017 Wrth lunio'r disgrifiad hwn dilynwyd canllawiau ANW a seiliwyd ar ISAD(G) Ail Argraffiad; rheolau AACR2; ac LCSH Description follows ANW guidelines based on ISAD(G) 2nd ed.;AACR2; and LCSH https://archifau.llyfrgell.cymru/index.php/thomas-edward-ellis-papers-2 archives.library .wales/index.php/thomas-edward-ellis-papers-2 Llyfrgell Genedlaethol Cymru = The National Library of Wales Allt Penglais Aberystwyth Ceredigion United Kingdom SY23 3BU 01970 632 800 01970 615 709 [email protected] www.llgc.org.uk Thomas Edward Ellis Papers Tabl cynnwys | Table of contents Gwybodaeth grynodeb | Summary information .............................................................................................. 3 Hanes gweinyddol / Braslun bywgraffyddol | Administrative history | Biographical sketch ......................... 4 Natur a chynnwys | Scope and content .......................................................................................................... 4 Trefniant | Arrangement .................................................................................................................................. 5 Nodiadau | Notes ............................................................................................................................................. 5 Pwyntiau -

ISSUE 3—MANTELL GWYNEDD INFORMATION BULLETIN DURING the COVID-19 PANDEMIC Mantell Gwynedd Supports Community and Voluntary

ISSUE 3—MANTELL GWYNEDD INFORMATION BULLETIN DURING THE COVID-19 PANDEMIC SPECIAL EXTENDED BULLETIN TO CELEBRATE VOLUNTEERS’ WEEK Mantell Gwynedd supports community and voluntary groups, promotes and coordinates volunteering in Gwynedd and is a strong voice for the Third Sector in the county We will be producing a regular Bulletin during the COVID-19 pandemic to keep you informed about what’s going on, what services are available and how we can help you. DON’T FORGET! Mantell Gwynedd’s staff members are all working during this period and you can still get in touch with MANTELL GWYNEDD’S COVID-19 SMALL GRANTS FUND us via the usual telephone numbers, Mantell Gwynedd received funding from Welsh Government to create a small grants 01286 672 626 or 01341 422 575. fund to assist third sector organisations working in Gwynedd during the Covid-19 Your calls will be answered in the usual pandemic. way and your message will be passed on Congratulations to all the organisations who have so far successfully applied for funding: to the relevant staff member. Porthi Pawb Caernarfon, GISDA, Crossroads, Help Harlech, Seren Blaenau Ffestiniog, Banc Bwyd Nefyn, Prosiect Cymunedol Llandwrog, Gwallgofiaid Blaenau Ffestiniog, Siop Griffiths Penygroes, Gweithgor Cymunedol Llanbedr, Egni Abergynolwyn, Prosiect Braich Coch Inn Corris, Prosiect Neuadd Llanllyfni , Prosiect Sign, Sight & Sound, Llygaid Maesincla, Datblygiadau Egni Gwledig (D.E.G.), Prosiect Peblig, Menter y Plu Llanystumndwy, Menter Fachwen, Grŵp Ffermwyr a Garddio, Pecynnau Codi Calon y Groeslon, Maes Ni. One of the organisations that has received funding is the Porthi Pawb Community Food Project in Caernarfon: Porthi Pawb received a sum of £1000 from Mantell Gwynedd to assist local volunteers with the task of preparing, cooking and distributing cooked meals to the elderly and vulnerable in the Caernarfon area. -

Appendix 2Ch

2021/22 Bids Appendix 2ch 2021/22 CAPITAL BIDS - TO BE FUNDED FROM THE BUDGET WITHIN THE ASSET MANAGEMENT PLAN Recommended Bid Title Details of the Bid Sum (£) ADULTS, HEALTH AND WELL-BEING Cap 1 Renewal of WCCIS National Hardware There is a need to renew the WCCIS national infrastructure in 30,000 accordance with the contract. This includes servers, CRM licences etc. Every Authority and Health Board that uses the system must contribute towards the amount of £1.93m based on a formula, with Welsh Government contributing over £600k. HIGHWAYS AND MUNICIPAL Cap 2 Flare to deal with gases on the Cilgwyn For the past 15+ years, the site's landfill gas control was 60,600 landfill site contracted externally, by now the gas control is managed internally again. The volume and standard of gas has reduced to a level where only a low calorific gas flare has the ability to sufficiently control the remaining gas. It is intended to purchase specific equipment to burn poor quality landfill gas - this is the best technique available to control and deal with poor land quality / volume of landfill gas effectively. Cap 3 Dolgellau Workshop Inspection Pit Vehicle inspection facilities have deteriorated substantially at the 65,000 Depo, which creates a risk of injury and service continuation in the Meirionnydd area. Therefore, an application is made to purchase two specific inspection pits for the workshop in order to safeguard our staff and to ensure service continuation. ECONOMY AND COMMUNITY Cap 4 Community Support Fund (Cist CIST Gwynedd provides revenue and capital grants to voluntary 50,000 Gwynedd) groups across the county to develop and realise comunity projects. -

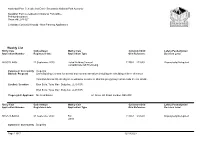

Weekly List Rhif Y Cais Cofrestrwyd Math Y Cais Cyfeirnod Grid Lefel Y Penderfyniad Application Number Registered Date Application Type Grid Reference Decision Level

Awdurdod Parc Cenedlaethol Eryri - Snowdonia National Park Authority Swyddfa'r Parc Cenedlaethol / National Park Office Penrhyndeudraeth Gwynedd LL48 6LF Ceisiadau Cynllunio Newydd - New Planning Applicatons Weekly List Rhif y Cais Cofrestrwyd Math y Cais Cyfeirnod Grid Lefel y Penderfyniad Application Number Registered date Application Type Grid Reference Decision Level NP5/57/LB408 21 September 2020 Listed Building Consent 317563 272659 Dirprwyiedig/Delegated Caniatâd Adeilad Rhestredig Cymuned / Community Dolgellau Bwriad / Proposal Listed Building Consent for internal and external alterations including the rebuilding of three chimneys Caniatâd Adeilad Rhestredig am newidiadau mewnol ac allannol gan gynnwys ail adeiladu tri corn simdde Lleoliad / Location Bryn Bella, Tylau Mair, Dolgellau. LL40 1SR Bryn Bella, Tylau Mair, Dolgellau. LL40 1SR Ymgeisydd / Applicant Mr Giles Baxter 61 Grove Hill Road, London, SE5 8DF Rhif y Cais Cofrestrwyd Math y Cais Cyfeirnod Grid Lefel y Penderfyniad Application Number Registered date Application Type Grid Reference Decision Level NP5/57/LB408A 21 September 2020 Full 317563 272659 Dirprwyiedig/Delegated Llawn Cymuned / Community Dolgellau Page 1 Of 7 12/10/2020 Bwriad / Proposal External alterations including the rebuilding of three chimneys Newidiadau allannol gan gynnwys ail adeiladu tri corn simdde Lleoliad / Location Bryn Bella, Tylau Mair, Dolgellau. LL40 1SR Bryn Bella, Tylau Mair, Dolgellau. LL40 1SR Ymgeisydd / Applicant Mr Giles Baxter 61 Grove Hill Road, London, SE5 8DF Rhif y Cais Cofrestrwyd Math y Cais Cyfeirnod Grid Lefel y Penderfyniad Application Number Registered date Application Type Grid Reference Decision Level NP2/11/T528B 21 September 2020 Full 351420 263635 Dirprwyiedig/Delegated Llawn Cymuned / Community Beddgelert Bwriad / Proposal Insertion of rooflight windows to rear elevation Gosod ffenestri to yn y drychiad cefn Lleoliad / Location Ysgoldy, Nant Gwynant. -

Inspection Report Ysgol Gynradd Tudweiliog ENG 2012

A report on Ysgol Gynradd Tudweiliog Tudweiliog Pwllheli Gwynedd LL53 8ND Date of inspection: January 2012 by Estyn, Her Majesty’s Inspectorate for Education and Training in Wales During each inspection, inspectors aim to answer three key questions: Key Question 1: How good are the outcomes? Key Question 2: How good is provision? Key Question 3: How good are leadership and management? Inspectors also provide an overall judgement on the school’s current performance and on its prospects for improvement. In these evaluations, inspectors use a four-point scale: Judgement What the judgement means Excellent Many strengths, including significant examples of sector-leading practice Good Many strengths and no important areas requiring significant improvement Adequate Strengths outweigh areas for improvement Unsatisfactory Important areas for improvement outweigh strengths The report was produced in accordance with Section 28 of the Education Act 2005. Every possible care has been taken to ensure that the information in this document is accurate at the time of going to press. Any enquiries or comments regarding this document/publication should be addressed to: Publication Section Estyn Anchor Court Keen Road Cardiff CF24 5JW or by email to [email protected] This and other Estyn publications are available on our website: www.estyn.gov.uk This report has been translated by Trosol (Welsh to English). © Crown Copyright 2012: This report may be re-used free of charge in any format or medium provided that it is re-used accurately and not used in a misleading context. The material must be acknowledged as Crown copyright and the title of the report specified. -

Princes of Gwynedd Guidebook

Princes of Gwynedd Guidebook Discover the legends of the mighty princes of Gwynedd in the awe-inspiring landscape of North Wales PRINCES OF GWYNEDD GUIDEBOOK Front Cover: Criccieth Castle2 © Princes of Gwynedd 2013 of © Princes © Cadw, Welsh Government (Crown Copyright) This page: Dolwyddelan Castle © Conwy County Borough Council PRINCES OF GWYNEDD GUIDEBOOK 3 Dolwyddelan Castle Inside this book Step into the dramatic, historic landscapes of Wales and discover the story of the princes of Gwynedd, Wales’ most successful medieval dynasty. These remarkable leaders were formidable warriors, shrewd politicians and generous patrons of literature and architecture. Their lives and times, spanning over 900 years, have shaped the country that we know today and left an enduring mark on the modern landscape. This guidebook will show you where to find striking castles, lost palaces and peaceful churches from the age of the princes. www.snowdoniaheritage.info/princes 4 THE PRINCES OF GWYNEDD TOUR © Sarah McCarthy © Sarah Castell y Bere The princes of Gwynedd, at a glance Here are some of our top recommendations: PRINCES OF GWYNEDD GUIDEBOOK 5 Why not start your journey at the ruins of Deganwy Castle? It is poised on the twin rocky hilltops overlooking the mouth of the River Conwy, where the powerful 6th-century ruler of Gwynedd, Maelgwn ‘the Tall’, once held court. For more information, see page 15 © Princes of Gwynedd of © Princes If it’s a photo opportunity you’re after, then Criccieth Castle, a much contested fortress located high on a headland above Tremadog Bay, is a must. For more information, see page 15 © Princes of Gwynedd of © Princes If you prefer a remote, more contemplative landscape, make your way to Cymer Abbey, the Cistercian monastery where monks bred fine horses for Llywelyn ap Iorwerth, known as Llywelyn ‘the Great’. -

Y Pwyllgor Iechyd, Gofal Cymdeithasol a Chwaraeon Health, Social Care and Sport Committee HSCS(5)-23-17 Papur 1 / Paper 1

Y Pwyllgor Iechyd, Gofal Cymdeithasol a Chwaraeon Health, Social Care and Sport Committee HSCS(5)-23-17 Papur 1 / Paper 1 Tŷ Doctor, Ffordd Dewi Sant, Nefyn. Pwllheli. Gwynedd. LL53 6EG XXXXXXXXXX XXXXXXXXXX www.tydoctor.wales.nhs.uk 10 April 2017 Dr Dai Lloyd Mr Rhun Ap Iorwerth National Assembly for Wales Cardiff Bay CARDIFF CF99 1NA Annwyl Dai a Rhun, Thank you for coming up to Caernarfon to meet with us last week. I hope you found it informative and useful for your ongoing enquiry. My name is Arfon Williams and I have been a General Practitioner in Nefyn for the past 22 years. Unfortunately, I am the sole partner in the practice, caring for about 4300 patients, extending along the north tip of the Llyn Peninsula from Aberdaron to Clynnog Fawr. We have found it very difficult to recruit and we have had to change our whole work model in order to continue to provide a service to our patients in a safe way. The last two years have been incredibly difficult, and without the support of my excellent staff, it would have been virtually impossible for us to carry on. We have made some significant changes to the way we provide medical care, in that we have changed our skill mix, capacity, working day etc. I enclose a letter that I sent to the Betsi Cadwaladr University Health Board to explain to them the methods we have introduced in order that they might be able to disseminate that information to help others in a similar predicament. To the best of my knowledge, I do not think that this information has been shared (which is disappointing). -

A Welsh Classical Dictionary

A WELSH CLASSICAL DICTIONARY DACHUN, saint of Bodmin. See s.n. Credan. He has been wrongly identified with an Irish saint Dagan in LBS II.281, 285. G.H.Doble seems to have been misled in the same way (The Saints of Cornwall, IV. 156). DAGAN or DANOG, abbot of Llancarfan. He appears as Danoc in one of the ‘Llancarfan Charters’ appended to the Life of St.Cadog (§62 in VSB p.130). Here he is a clerical witness with Sulien (presumably abbot) and king Morgan [ab Athrwys]. He appears as abbot of Llancarfan in five charters in the Book of Llandaf, where he is called Danoc abbas Carbani Uallis (BLD 179c), and Dagan(us) abbas Carbani Uallis (BLD 158, 175, 186b, 195). In these five charters he is contemporary with bishop Berthwyn and Ithel ap Morgan, king of Glywysing. He succeeded Sulien as abbot and was succeeded by Paul. See Trans.Cym., 1948 pp.291-2, (but ignore the dates), and compare Wendy Davies, LlCh p.55 where Danog and Dagan are distinguished. Wendy Davies dates the BLD charters c.A.D.722 to 740 (ibid., pp.102 - 114). DALLDAF ail CUNIN COF. (Legendary). He is included in the tale of ‘Culhwch and Olwen’ as one of the warriors of Arthur's Court: Dalldaf eil Kimin Cof (WM 460, RM 106). In a triad (TYP no.73) he is called Dalldaf eil Cunyn Cof, one of the ‘Three Peers’ of Arthur's Court. In another triad (TYP no.41) we are told that Fferlas (Grey Fetlock), the horse of Dalldaf eil Cunin Cof, was one of the ‘Three Lovers' Horses’ (or perhaps ‘Beloved Horses’). -

Code-Switching and Mutation As Stylistic and Social Markers in Welsh

Bangor University DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Style in the vernacular and on the radio: code-switching and mutation as stylistic and social markers in Welsh Prys, Myfyr Award date: 2016 Awarding institution: Bangor University Link to publication General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal ? Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 06. Oct. 2021 Style in the vernacular and on the radio: code-switching and mutation as stylistic and social markers in Welsh Myfyr Prys School of Linguistics and English language Bangor University PhD 2016 Abstract This thesis seeks to analyse two types of linguistic features of Welsh, code-switching and mutation, as sociolinguistic variables: features which encode social information about the speaker and/or stylistic meaning. Developing a study design that incorporates an analysis of code-switching and mutation in naturalistic speech has demanded a relatively novel methodological approach. The study combined a variationist analysis of the vernacular use of both variables in the 40-hour Siarad corpus (Deuchar 2014) with a technique that ranks radio programmes in order of formality through the use of channel cues and other criteria (Ball et al 1988). -

The Llyn Ac Eifionydd Junior Football League Constitutional Rules Part 1

TYMOR 2015-16 LLAWLYFR CLYBIAU Cynghrair Pêl -Droed Iau Llŷn & Eifionydd Junior Football League CLUBS HANDBOOK SEASON 2015 - 2016 1 SWYDDOGION Y GYNGHRAIR – LEAGUE OFFICERS SAFLE ENW CYFEIRIAD FFÔN E-BOST POSITION NAME ADDRESS PHONE E-MAIL CADEIRYDD Darren Vaughan Tegfryn 07949429380 CHAIRMAN Bryncrug LL36 9PA YSGRIFENNYDD SECRETARY IS-GADEIRYDD VICE CHAIRMAN YSGRIFENNYDD Colin Dukes 41 Adwy Ddu 01766770854 [email protected] GEMAU Penrhyndeudraeth anadoo.co.uk Gwynedd 07863348589 FIXTURE LL48 6AP SECRETARY YSGRIFENNYDD Vicky Jones Dolgellau COFRESTRU REGISTRATION SECRETARY SWYDDOG LLES Ivonica Jones Fflur y Main 01766 810671 tjones.llynsports@ Ty’n Rhos btinternet.com Chwilog, 07884161807 WELFARE Pwllheli OFFICER LL53 6SF TRYSORYDD Andrew Roberts 8 Bowydd View 07787522992 [email protected] Blaenau Ffestiniog m Gwynedd TREASURER LL41 3YW NWCFA REP Chris Jones Pentwyll 01758740521 [email protected] Mynytho 07919098565 Pwllheli CYN. NWCFA LL53 7SD 2 CLYBIAU A’U TIMAU - CLUBS AND THEIR TEAMS U6 U8 U10 U12 U14 U16 BARMOUTH JUNIORS X2 BLAENAU AMATEURS BRO DYSYNNI BRO HEDD WYN CELTS DOLGELLAU LLANYSTUMDWY PENLLYN – NEFYN PENRHYN JUNIORS PORTHMADOG JUNIORS PWLLHELI JUNIORS x 2 x 3 3 YSGRIFENYDD CLYBIAU -– CLUB SECRETERIES CLWB CYSWLLT CYFEIRIAD CLUB CONTACT ADDRESS BARMOUTH JUNIORS Alan Mercer Wesley House 01341 529 Bennar Terrace [email protected] Barmouth GwyneddLL42 1BT BLAENAU AMATEURS Mr Andrew Roberts 8 Bowydd View 07787522992 Blaenau Ffestiniog [email protected] Gwynedd LL41 3YW BRO DYSYNNI Lorraine Rodgers Bryn Awel 01341250404 Llwyngwril 07882153373 Gwynedd [email protected] LL37 2JQ BRO HEDD WYN CELTS Gareth Lewis Bryn Eithin 07788553231 Bryn Eithin [email protected] Trawsfynydd Gwynedd DOLGELLAU Mr Stephen Parry BRYN Y GWIN UCHAF, 01341423935 DOLGELLAU. -

Quarries and Mines

Quarries and Mines Quarries of Pistyll and Nefyn There were two other quarries close to Pistyll village – Chwarel Tŷ Mawr (quarry + Tŷ Mawr) and Chwarel There were a number of small quarries between Carreg Bodeilias (quarry + Bodeilias) (SH 32004160). They y Llam and Nefyn, the working conditions just as hard were also productive at one time, and exporting from but they provided people with a wage at difficult times. Doc Bodeilias (dock + Bodeilias) (SH 3190422). The In Nefyn, there were 58 men working in the quarries work came to an end in the early years of the C20th but in 1851, but with the demand for setts increasing and there are still remains to be seen. quarries opening more people moved into the area, Chwarel Moel Tŷ Gwyn (quarry+ bare hill + white particularly to Pistyll parish, according to the 1881 house), Pistyll was opened in 1864 and Chwarel Moel census. Dywyrch (quarry + bare hill + sods) high up on Mynydd Chwarel y Gwylwyr (quarry + Gwylwyr) (SH 31904140) Nefyn near Carreg Lefain (rock + echo) in 1881. They above Nefyn opened in the 1830s. An incline ran from closed in the early C20th. the quarry, across the road and down to the jetty on Chwarel John Lloyd (Quarry + John Lloyd) on the slopes Wern beach (and its remains are still to be seen). The of Mynydd Nefyn was working from 1866 onwards, but setts would be loaded onto ships, usually ones owned closed for some periods and closed finally in 1937. One by the quarry owners. of its owners was John Lloyd Jones of Llandwrog.