THE WAY a Review of Christian Spirituality Published by the British Jesuits

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Princes of Gwynedd Guidebook

Princes of Gwynedd Guidebook Discover the legends of the mighty princes of Gwynedd in the awe-inspiring landscape of North Wales PRINCES OF GWYNEDD GUIDEBOOK Front Cover: Criccieth Castle2 © Princes of Gwynedd 2013 of © Princes © Cadw, Welsh Government (Crown Copyright) This page: Dolwyddelan Castle © Conwy County Borough Council PRINCES OF GWYNEDD GUIDEBOOK 3 Dolwyddelan Castle Inside this book Step into the dramatic, historic landscapes of Wales and discover the story of the princes of Gwynedd, Wales’ most successful medieval dynasty. These remarkable leaders were formidable warriors, shrewd politicians and generous patrons of literature and architecture. Their lives and times, spanning over 900 years, have shaped the country that we know today and left an enduring mark on the modern landscape. This guidebook will show you where to find striking castles, lost palaces and peaceful churches from the age of the princes. www.snowdoniaheritage.info/princes 4 THE PRINCES OF GWYNEDD TOUR © Sarah McCarthy © Sarah Castell y Bere The princes of Gwynedd, at a glance Here are some of our top recommendations: PRINCES OF GWYNEDD GUIDEBOOK 5 Why not start your journey at the ruins of Deganwy Castle? It is poised on the twin rocky hilltops overlooking the mouth of the River Conwy, where the powerful 6th-century ruler of Gwynedd, Maelgwn ‘the Tall’, once held court. For more information, see page 15 © Princes of Gwynedd of © Princes If it’s a photo opportunity you’re after, then Criccieth Castle, a much contested fortress located high on a headland above Tremadog Bay, is a must. For more information, see page 15 © Princes of Gwynedd of © Princes If you prefer a remote, more contemplative landscape, make your way to Cymer Abbey, the Cistercian monastery where monks bred fine horses for Llywelyn ap Iorwerth, known as Llywelyn ‘the Great’. -

A Welsh Classical Dictionary

A WELSH CLASSICAL DICTIONARY DACHUN, saint of Bodmin. See s.n. Credan. He has been wrongly identified with an Irish saint Dagan in LBS II.281, 285. G.H.Doble seems to have been misled in the same way (The Saints of Cornwall, IV. 156). DAGAN or DANOG, abbot of Llancarfan. He appears as Danoc in one of the ‘Llancarfan Charters’ appended to the Life of St.Cadog (§62 in VSB p.130). Here he is a clerical witness with Sulien (presumably abbot) and king Morgan [ab Athrwys]. He appears as abbot of Llancarfan in five charters in the Book of Llandaf, where he is called Danoc abbas Carbani Uallis (BLD 179c), and Dagan(us) abbas Carbani Uallis (BLD 158, 175, 186b, 195). In these five charters he is contemporary with bishop Berthwyn and Ithel ap Morgan, king of Glywysing. He succeeded Sulien as abbot and was succeeded by Paul. See Trans.Cym., 1948 pp.291-2, (but ignore the dates), and compare Wendy Davies, LlCh p.55 where Danog and Dagan are distinguished. Wendy Davies dates the BLD charters c.A.D.722 to 740 (ibid., pp.102 - 114). DALLDAF ail CUNIN COF. (Legendary). He is included in the tale of ‘Culhwch and Olwen’ as one of the warriors of Arthur's Court: Dalldaf eil Kimin Cof (WM 460, RM 106). In a triad (TYP no.73) he is called Dalldaf eil Cunyn Cof, one of the ‘Three Peers’ of Arthur's Court. In another triad (TYP no.41) we are told that Fferlas (Grey Fetlock), the horse of Dalldaf eil Cunin Cof, was one of the ‘Three Lovers' Horses’ (or perhaps ‘Beloved Horses’). -

A Description of What Magisterial Authority Is When Understood As A

Cultural Heritage and Contemporary Change Series IV, Western Philosophical Studies, Volume 8 Series VIII, Christian Philosophical Studies, Volume 8 General Editor George F. McLean Towards a Kenotic Vision of Authority in the Catholic Church Western Philosophical Studies, VIII Christian Philosophical Studies, VIII Edited by Anthony J. Carroll Marthe Kerkwijk Michael Kirwan James Sweeney The Council for Research in Values and Philosophy Copyright © 2015 by The Council for Research in Values and Philosophy Box 261 Cardinal Station Washington, D.C. 20064 All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Towards a kenotic vision of authority in the Catholic Church / edited by Anthony J. Carroll, Marthe Kerkwijk, Michael Kirwan, James Sweeney. -- first edition. pages cm. -- (Cultural heritage and contemporary change. Christian philosophical studies; Volume VIII) Includes bibliographical references and index. 1. Authority--Religious aspects--Catholic Church. I. Carroll, Anthony J., 1965- editor of compilation. BX1753.T6725 2014 2014012706 262'.'088282--dc23 CIP ISBN 978-1-56518-293-6 (pbk.) TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction: The Exercise of Magisterial Authority 1 in the Roman Catholic Church Anthony J. Carroll Part I: Authority in Biblical Sources Chapter I: “It Shall Not Be so among You”: Authority and 15 Service in the Synoptic Gospels Sean Michael Ryan Chapter II: Authority without Sovereignty: Towards 41 a Reassessment of Divine Power Roger Mitchell Part II: Sociological and Philosophical -

The North Wales Pilgrim's Way. Spiritual Re

27 The North Wales Pilgrim’s Way. Spiritual re- vival in a marginal landscape. DANIELS Andrew Abstract The 21st century has seen a marked resurgence in the popularity of pilgrim- age routes across Europe. The ‘Camino’ to Santiago de Compostela in Spain and routes in England to Walsingham in Norfolk and Canterbury in Kent are just three well-known examples where numbers of pilgrims have increased dramati- cally over the last decade. The appeal to those seeking religious as well as non- spiritual self-discovery has perhaps grown as the modern world has become ever more complicated for some. The North Wales Pilgrim’s Way is another ancient route that has once again seen a marked increase in participants during recent years. Various bodies have attempted to appropriate this spiritual landscape in or- der to attract modern pilgrims. Those undertaking the journey continue to leave their own imprints on this marginal place. Year by year they add further layers of meaning to those that have already been laid down over many centuries of pil- grimage. This short paper is the second in a series of research notes looking specifically at overlapping spiritual and tourist connections in what might be termed ‘periph- eral landscapes’ in remote coastal areas of Britain. In particular I will focus on how sites connected with early Celtic Christianity in Britain have been used over time by varying groups with different agendas. In the first paper in this series, I explored how the cult of St. Cuthbert continues to draw visitors to Lindisfarne or Holy Island in the North East of England. -

Sourozh Messenger May 2017 Ascension of the Lord 13/26 May 2017

RUSSIAN ORTHODOX CHURCH DIOCESE OF SOUROZH CATHEDRAL OF THE DORMITION OF THE MOTHER OF GOD 67 ENNISMORE GARDENS, LONDON SW7 1NH Sourozh Messenger May 2017 Ascension of the Lord 13/26 May 2017 Troparion Thou art ascended in glory, O Christ our God, having filled Thy disciples with joy by the promise of the Holy Spirit; for they were assured by Thy blessing that Thou art the Son of God, the Redeemer of the world. Kontakion When Thou hadst accomplished Thy dispensation towards us, and hadst united things on earth with those in heaven, Thou didst ascend in glory, O Christ our God, in no way parted, but remaining continually with us. Thou didst cry to those who love Thee: I am with you and none shall be against you! May 2017 List of contents In this issue: IN THE footstePS OF THE Pilgrims Greetings to Archbishop Impressions of the Diocesan Anatoly.......................................................3 pilgrimage to the Holy Land DIOCESAN NEWS................................4 with the Russian Ecclesiastical Mission................................................17 Cathedral NEWS...........................5 Pilgrimage to the Holy Relics of LegacY OF MetroPolitan St Nicholas the Wonderworker ANTHONY OF Sourozh Sermon on the Feast of in Bari..................................................21 the Ascension..........................................7 HOLY Places IN LONDON BRITISH AND IRISH SAINTS St Paul’s Cathedral.............................23 Venerable Beuno, Abbot of Everlasting Art of Iconography..25 Clynnog Fawr..................................9 cathedral NEWSLETTER Notes ON THE church 30 YEARS ago calendar Metropolitan Anthony has sent Ascension of Our Lord................13 this communication Sacraments OF THE church Youth discuss faith..........................31 Part 5. Penance................................15 Recommended donation is £1 Dear Readers, We are happy to inform you that the Media and Publishing Department of the Diocese of Sourozh now has an online store, Sourozh Publications, where you can obtain the publications of the diocese. -

Then Arthur Fought the MATTER of BRITAIN 378 – 634 A.D

Then Arthur Fought THE MATTER OF BRITAIN 378 – 634 A.D. Howard M. Wiseman Then Arthur Fought is a possible history centred on a possi- bly historical figure: Arthur, battle-leader of the dark-age (5th- 6th century) Britons against the invading Anglo-Saxons. Writ- ten in the style of a medieval chronicle, its events span more than 250 years, and most of Western Europe, all the while re- specting known history. Drawing upon hundreds of ancient and medieval texts, Howard Wiseman mixes in his own inventions to forge a unique conception of Arthur and his times. Care- fully annotated, Then Arthur Fought will appeal to anyone in- terested in dark-age history and legends, or in new frameworks for Arthurian fiction. Its 430 pages include Dramatis Personae, genealogies, notes, bibliography, and 20 maps. —— Then Arthur Fought is an extraordinary achievement. ... An absorbing introduction to the history and legends of the period [and] ... a fascinating synthesis. — from the Foreword by Patrick McCormack, author of the Albion trilogy. —— A long and lavishly detailed fictional fantasia on the kind of primary source we will never have for the Age of Arthur. ... soaringly intelligent and, most unlikely of all, hugely entertaining. It is a stunning achievement, enthusiastically recommended. — Editor’s Choice review by Steve Donoghue, Indie Reviews Editor, Historical Novel Society. Contents List of Figures x Foreword, by Patrick McCormack xi Preface, by the author xv Introduction: history, literature, and this book xix Dramatis Personae xxxi Genealogies xxxix -

The Theological Project of James Alison Grant Kaplan of Many Things Published by Jesuits of the United States

THE NATIONAL CATHOLIC WEEKLY MAY 19, 2014 $3.50 The Theological Project of James Alison GRANT KAPLAN OF MANY THINGS Published by Jesuits of the United States 106 West 56th Street hen we hear “The harvest behaviors such as selfishness, collective New York, NY 10019-3803 is abundant but the greed and the hoarding of goods on Ph: 212-581-4640; Fax: 212-399-3596 laborers are few,” our a mammoth scale.” In the preface, Subscriptions: 1-800-627-9533 W www.americamagazine.org minds turn at once to priestly or Cardinal Peter Turkson said everyone facebook.com/americamag missionary vocations. But there’s more is called “to examine in depth the twitter.com/americamag to it than that: The Gospel of Luke principles and the cultural and moral isn’t just describing a labor shortage. It values that underlie social coexistence.” PRESIDENT AND EDITOR IN CHIEF is important to keep in mind that the As this week’s editorial points out, we Matt Malone, S.J. only reason there is a labor shortage is would do well at this moment to recall EXECUTIVE EDITORS that there is an abundance in the first this truth. Robert C. Collins, S.J., Maurice Timothy Reidy place. Before we get to any practical In other words, we need to MANAGING EDITOR Kerry Weber questions, then, we might profit from remember who we are: gifts of God LITERARY EDITOR Raymond A. Schroth, S.J. some reflection on what a marvelous who are called to give in return. No SENIOR EDITOR AND CHIEF CORRESPONDENT thing it is that the vineyard exists at all, one is saying that being a banker or a Kevin Clarke for this reminds us of the primordial business executive is necessarily a bad EDITOR AT LARGE James Martin, S.J. -

Durham Research Online

Durham Research Online Deposited in DRO: 06 February 2018 Version of attached le: Accepted Version Peer-review status of attached le: Peer-reviewed Citation for published item: Loughlin, Gerard (2018) 'Catholic homophobia.', Theology., 121 (3). pp. 188-196. Further information on publisher's website: https://doi.org/10.1177/0040571x17749147 Publisher's copyright statement: Loughlin, Gerard (2018). Catholic Homophobia. Theology 121(3): 188-196. Copyright c 2018 The Author(s). Reprinted by permission of SAGE Publications. Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in DRO • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full DRO policy for further details. Durham University Library, Stockton Road, Durham DH1 3LY, United Kingdom Tel : +44 (0)191 334 3042 | Fax : +44 (0)191 334 2971 https://dro.dur.ac.uk Catholic homophobia1 Gerard Loughlin Durham University Corresponding author: Gerard Loughlin Email: [email protected] Abstract Understanding homophobia as a discursively constituted antipathy, this article argues that the culture of the Catholic Church – as constituted through the Roman magisterium – can be understood as fundamentally homophobic, and in its teaching not just on homosexuality, but also on contraception and priestly celibacy. -

A Girardian Study of Popular English Evangelical Writings on Homosexuality 1960-2010

Durham E-Theses The Problem of English Evangelicals and Homosexuality: A Girardian Study of Popular English Evangelical Writings on Homosexuality 1960-2010 VASEY-SAUNDERS, MARK,RICHARD How to cite: VASEY-SAUNDERS, MARK,RICHARD (2012) The Problem of English Evangelicals and Homosexuality: A Girardian Study of Popular English Evangelical Writings on Homosexuality 1960-2010 , Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/7009/ Use policy This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution Non-commercial No Derivatives 3.0 (CC BY-NC-ND) Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk 2 Abstract The Problem of English Evangelicals and Homosexuality: A Girardian Study of Popular English Evangelical Writings on Homosexuality 1960-2010 Mark Vasey-Saunders English evangelicals in the period 1960-2010 have been marked by their negativity and violence towards gays. However, they have also consistently condemned homophobia during this period (and often seemed unaware of their own complicity in it). This thesis draws on the work of René Girard to analyse popular English evangelical writings and the ways in which they have implicitly encouraged violence against gays even whilst explicitly condemning it. This analysis of evangelical writings on homosexuality is placed in its historical context by drawing on the work of relevant historians and social scientists. It is further contextualised by reference to an analysis of evangelical writings on holiness during the same period. The thesis argues that English evangelical violence towards gays is a byproduct of internal conflicts within English evangelicalism. -

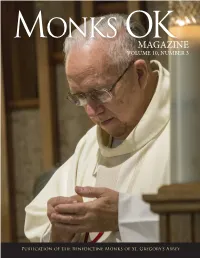

Monks Okmagazine Volume 10, Number 3

MONKS OKMAGAZINE VOLUME 10, NUMBER 3 Publication of the Benedictine Monks of St. Gregory’s Abbey Gaudete!REFLECTIONS FROM ABBOT LAWRENCE Sometimes people are or attend regional meetings without having to leave surprised when they learn the monastery. Various social media make it possible just how much monks for monks to share their faith experience with others make use of modern or to help young people discern where God is calling technologies. Access to the them. Recently, we at St. Gregory’s Abbey began to use Internet, “smart” phones, “Flocknote” to share news and reflections with Oblates tablets, fitness trackers and and friends of the Abbey. other 21st century marvels is possible for many in consecrated life – including But for all the good that new technologies bring, they monks and nuns. also can bring a dark side. All the distractions of the world can easily invade the life of a monk with the Monks and nuns often have been early adopters simple click of a mouse. Even seemingly innocent and inventors of new technologies. Medieval monks websites and a desire to keep-up with social media can developed time-keeping devices, agricultural become destructive to what should be a life of quiet techniques, architectural designs and educational reflection, prayer and work. The walls of the monastery tools. For instance, the monks of Subiaco Abbey in and a locked cloister gate are not enough to prevent Italy, founded by St. Benedict himself, installed the such invasions of the sanctuary of monastic enclosure. first printing press in Italy in the year 1464 – just 30 years after Gutenberg introduced the printing press in To prevent unhealthy distractions, communities Germany. -

Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-18045-1 — Gerard Manley Hopkins and the Poetry of Religious Experience Martin Dubois Index More Information

Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-18045-1 — Gerard Manley Hopkins and the Poetry of Religious Experience Martin Dubois Index More Information Index Acts of the Apostles, The, 31 Boer War, First, 86, 91–93 Addis, William Edward, 42, 169 Book of Common Prayer, 31, 35, 45, 47, 179n.15, Alderson, David, 91, 94, 197n.47 180n.25 alexandrine, 150 Bremond, Henri, 62 alliteration, 95, 104–105, 159 Bridges, Robert, 1, 5, 13, 15, 19, 28, 31, 39, 55, 64, Anglican Church. See Church of England 65, 66, 85, 86, 91, 92, 94, 95, 96, 98, 99, Anglo-Saxon verse, 104, 145 101, 108, 110, 138, 150, 166, 171 Anselm of Canterbury, St, 144 and exchanges with Hopkins over poetry, 138 apocalypse, 89, 142, 143, 146, 148 Hopkins’s occasional pieces, opinion of, 57–58 Aquinas, St Thomas, 18, 20, 55, 162 Jesuit ideals, dislike of, 106 Ariès, Phillipe, 161 and naming of ‘terrible sonnets’, 185 Armstrong, Isobel, 8, 54 and The Spirit of Man, 83 Arnold, Thomas, 169 ‘The Windhover’, transcription of, 15 asceticism, 23, 79, 85, 87, 91, 104, 108, 169, 171 ‘The Wreck’, opinion of, 108 assonance, 104, 159 Bristow, Joseph, 86, 88 Auden, W. H., 98 Brown, Daniel, 35, 104, 124, 174n.29, 186n.23, Augustine of Hippo, St, 65, 144 189n.71, 198n.61 Brueggemann, Walter, 50 Ball, Patricia, 159 Burgess, Anthony, 154 Ballinger, Philip A., 10, 174n.29, 177n.84, Burne-Jones, Edward, 110 178n.89, 178n.90, 189n.71, 190n.86 Butterfield, William, 7 Baring-Gould, Sabine, 88 Barnes, William, 141 Campbell, Matthew, 14, 89, 186n.25, 201n.26 beatific vision, 162–163 Campion, S.J., St Edmund, 114, -

Asceticism’ in Relation to the Report Issues in Human Sexuality, with Particular Reference to Queer Theology

A critical, theological analysis of meanings of ‘asceticism’ in relation to the report Issues in Human Sexuality, with particular reference to queer theology A thesis submitted to the University of Manchester for the Degree of Master of Philosophy in the Faculty of Humanities 2017 Mark J Williams School of Arts, Languages and Cultures Contents Chapter One Introduction 1) Issues in Human Sexuality. 7 2) What is asceticism? 10 3) Asceticism and sexual desire in Anglican thought. 12 4) An Anglican quest for holiness. 14 5) Definitions of celibacy. 17 6) Permanent, faithful and stable. 19 7) Queer theology. 25 8) Conclusion. 27 Chapter Two James Alison 1) Introduction. 28 2) The question of sin. 30 3) The ‘Gay Victim’. 31 4) Persecution by the church for being gay. 34 5) The desire for holiness. 36 6) Desire. 37 7) Sexual Desires. 40 8) Alison and identity. 41 9) Conclusions drawn from Alison’s writing. 43 Chapter Three Mark Jordan 1) Introduction. 45 2) The emerging contrast in history of sodomy being both evil and attractive. 47 3) Sex in the Reformation era. 48 4) Post reformation and the quest for power. 49 5) Asceticism and boundary. 50 6) Identity and holiness. 51 7) Jordan and ‘new holiness’. 52 8) Jordan’s understanding of freedom. 54 9) A return to the question of identity. 56 10) The challenge of a wider understanding of freedom. 57 Chapter Four Marcella Althaus-Reid 1) Introduction to complete liberation or freedom. 60 2) The Virgin of Guadalupe and the freedom of the female body. 60 3) Freedom to embrace indecency.