Zlatomir Fung, Cello

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Classical Station, WCPE 1 Start Runs Composer Title Performerslib # Label Cat

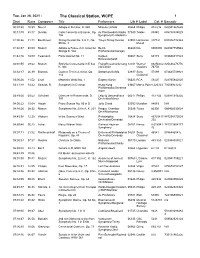

Tue, Jan 26, 2021 - The Classical Station, WCPE 1 Start Runs Composer Title PerformersLIb # Label Cat. # Barcode 00:01:30 10:39 Mozart Adagio in B minor, K. 540 Mitsuko Uchida 00264 Philips 412 616 028941261625 00:13:3945:17 Dvorak Cello Concerto in B minor, Op. du Pre/Swedish Radio 07040 Teldec 85340 685738534029 104 Symphony/Celibidache 01:00:2631:11 Beethoven String Quartet No. 9 in C, Op. Tokyo String Quartet 04508 Harmonia 807424 093046742362 59 No. 3 Mundi 01:32:3708:09 Mozart Adagio & Fugue in C minor for Berlin 06660 DG 0005830 028947759546 Strings K. 546 Philharmonic/Karajan 01:42:1618:09 Telemann Paris Quartet No. 11 Kuijken 04867 Sony 63115 074646311523 Bros/Leonhardt 02:01:5529:22 Mozart Sinfonia Concertante in E flat, Frang/Rysanov/Arcang 12341 Warner 08256462 825646276776 K. 364 elo/Cohen Classics 76776 02:32:1726:39 Brahms Clarinet Trio in A minor, Op. Stoltzman/Ax/Ma 02937 Sony 57499 074645749921 114 Classical 03:00:2611:52 Liszt Mephisto Waltz No. 1 Evgeny Kissin 06623 RCA 58420 828765842020 03:13:1834:42 Strauss, R. Symphony in D minor Hong Kong 03667 Marco Polo 8.220323 73009923232 Philharmonic/Scherme rhorn 03:49:0009:52 Schubert Overture to Rosamunde, D. Leipzig Gewandhaus 00217 Philips 412 432 028941243225 797 Orchestra/Masur 04:00:2215:04 Haydn Piano Sonata No. 50 in D Julia Cload 02053 Meridian 84083 N/A 04:16:2628:32 Mozart Symphony No. 29 in A, K. 201 Prague Chamber 05596 Telarc 80300 089408030024 Orch/Mackerras 04:45:58 12:20 Webern In the Summer Wind Philadelphia 10424 Sony 88725417 887254172024 Orchestra/Ormandy 202 04:59:4806:23 Lehar Merry Widow Waltz Richard Hayman 08261 Naxos 8.578041- 747313804177 Symphony 42 05:07:11 21:52 Rachmaninoff Rhapsody on a Theme of Entremont/Philadelphia 04207 Sony 46541 07464465412 Paganini, Op. -

The Musical Partnership of Sergei Prokofiev And

THE MUSICAL PARTNERSHIP OF SERGEI PROKOFIEV AND MSTISLAV ROSTROPOVICH A CREATIVE PROJECT SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT FOR THE DEGREE MASTER OF MUSIC IN PERFORMANCE BY JIHYE KIM DR. PETER OPIE - ADVISOR BALL STATE UNIVERSITY MUNCIE, INDIANA DECEMBER 2011 Among twentieth-century composers, Sergei Prokofiev is widely considered to be one of the most popular and important figures. He wrote in a variety of genres, including opera, ballet, symphonies, concertos, solo piano, and chamber music. In his cello works, of which three are the most important, his partnership with the great Russian cellist Mstislav Rostropovich was crucial. To understand their partnership, it is necessary to know their background information, including biographies, and to understand the political environment in which they lived. Sergei Prokofiev was born in Sontovka, (Ukraine) on April 23, 1891, and grew up in comfortable conditions. His father organized his general education in the natural sciences, and his mother gave him his early education in the arts. When he was four years old, his mother provided his first piano lessons and he began composition study as well. He studied theory, composition, instrumentation, and piano with Reinhold Glière, who was also a composer and pianist. Glière asked Prokofiev to compose short pieces made into the structure of a series.1 According to Glière’s suggestion, Prokofiev wrote a lot of short piano pieces, including five series each of 12 pieces (1902-1906). He also composed a symphony in G major for Glière. When he was twelve years old, he met Glazunov, who was a professor at the St. -

There's Even More to Explore!

Background artwork: SPECIAL COLLECTIONS UCHICAGO LIBRARY Kaplan and Fridkin, Agit No. 2 MUSIC THEATER ART MUSIC THEATER LECTURE / CLASS MUSIC MUSIC MUSIC / FILM LECTURE / CLASS MUSIC University of Chicago Presents University Theater/Theater and Performance Studies The University of Chicago Library Symphony Center Presents Goodman Theatre University of Chicago Presents Roosevelt University Rockefeller Chapel University of Chicago Presents TOKYO STRING QUARTET THEATER 24 PLAY SERIES: GULAG ART Orchestra Series CHEKHOv’S THE SEAGULL LECTURE / DEmoNSTRATioN PAciFicA QUARTET: 19TH ANNUAL SILENT FiLM LECTURE / DEmoNSTRATioN BY MARiiNskY ORCHESTRA FRIDAY, OCTOBER 1, 2010 A CLOUD WITH TROUSERS THROUGH DECEMBER 2010 OCTOber 16 – NOVEMBER 14, 2010 BY PACIFICA QUARTET SHOSTAKOVICH CYCLE WITH ORGAN AccomPANimENT: MAsumi RosTAD, VioLA, AND (FORMERLY KIROV ORCHESTRA) Mandel Hall, 1131 East 57th Street SATURDAY, OCTOBER 2, 2010, 8 PM The Joseph Regenstein Library, 170 North Dearborn Street SATURDAY, OCTOBER 16, 2 PM SUNDAY OCTOBER 17, 2010, 2 AND 7 PM AELITA: QUEEN OF MARS AMY BRIGGS, PIANO th nd chicagopresents.uchicago.edu, 773.702.8068 First Floor Theater, Reynolds Club, 1100 East 57 Street, 2 Floor Reading Room Valery Gergiev, conductor Goodmantheatre.org, 312.443.3800 Fulton Recital Hall, 1010 East 59th Street SUNDAY OCTOBER 31, 2010, 2 AND 7 PM Jay Warren, organ SATURDAY, OCTOBER 30, 2 PM 5706 South University Avenue Lib.uchicago.edu Denis Matsuev, piano Chicagopresents.uchicago.edu, 773.702.8068 FRIDAY, OCTOBER 29, 2010, 8 PM Fulton Recital Hall, 1010 East 59th Street Mozart: Quartet in C Major, K. 575 As imperialist Russia was falling apart, playwright Anton SUNDAY JANUARY 30, 2011, 2 AND 7 PM ut.uchicago.edu TUESDAY, OCTOBER 12, 2010, 8 PM Rockefeller Chapel, 5850 South Woodlawn Avenue Chicagopresents.uchicago.edu, 773.702.8068 Lera Auerbach: Quartet No. -

95.3 Fm 95.3 Fm

October/NovemberMarch/April 2013 2017 VolumeVolume 41, 46, No. No. 3 1 !"#$%&'95.3 FM Brahms: String Sextet No. 2 in G, Op. 36; Marlboro Ensemble Saeverud: Symphony No. 9, Op. 45; Dreier, Royal Philharmonic WHRB Orchestra (Norwegian Composers) Mozart: Clarinet Quintet in A, K. 581; Klöcker, Leopold Quartet 95.3 FM Gombert: Missa Tempore paschali; Brown, Henry’s Eight Nielsen: Serenata in vano for Clarinet,Bassoon,Horn, Cello, and October-November, 2017 Double Bass; Brynildsen, Hannevold, Olsen, Guenther, Eide Pokorny: Concerto for Two Horns, Strings, and Two Flutes in F; Baumann, Kohler, Schröder, Concerto Amsterdam (Acanta) Barrios-Mangoré: Cueca, Aire de Zamba, Aconquija, Maxixa, Sunday, October 1 for Guitar; Williams (Columbia LP) 7:00 am BLUES HANGOVER Liszt: Grande Fantaisie symphonique on Themes from 11:00 am MEMORIAL CHURCH SERVICE Berlioz’s Lélio, for Piano and Orchestra, S. 120; Howard, Preacher: Professor Jonathan L. Walton, Plummer Professor Rickenbacher, Budapest Symphony Orchestra (Hyperion) of Christian Morals and Pusey Minister in The Memorial 6:00 pm MUSIC OF THE SOVIET UNION Church,. Music includes Kodály’s Missa brevis and Mozart’s The Eve of the Revolution. Ave verum corpus, K. 618. Scriabin: Sonata No. 7, Op. 64, “White Mass” and Sonata No. 9, 12:30 pm AS WE KNOW IT Op. 68, “Black Mass”; Hamelin (Hyperion) 1:00 pm CRIMSON SPORTSTALK Glazounov: Piano Concerto No. 2 in B, Op. 100; Ponti, Landau, 2:00 pm SUNDAY SERENADE Westphalian Orchestra of Recklinghausen (Turnabout LP) 6:00 pm HISTORIC PERFORMANCES Rachmaninoff: Vespers, Op. 37; Roudenko, Russian Chamber Prokofiev: Violin Concerto No. 2 in g, Op. -

ONYX4090 Cd-A-Bklt V8 . 31/01/2012 16:49 Page 1 Page 16:49 31/01/2012 V8

ONYX4090_cd-a-bklt v8_. 31/01/2012 16:49 Page 1 p1 1 ONYX4090_cd-a-bklt v8_. 31/01/2012 16:49 Page 2 Variations on a Russian folk song for string quartet (1898, by various composers) Variationen über ein russisches Volkslied Variations sur un thème populaire russe 1 Theme. Adagio 0.56 2 Var. 1. Allegretto (Nikolai Artsybuschev) 0.40 3 Var. 2. Allegretto (Alexander Scriabin) 0.52 4 Var. 3. Andantino (Alexander Glazunov) 1.25 5 Var. 4. Allegro (Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov) 0.50 6 Var. 5. Canon. Adagio (Anatoly Lyadov) 1.19 7 Var. 6. Allegretto (Jazeps Vitols) 1.00 8 Var. 7. Allegro (Felix Blumenfeld) 0.58 9 Var. 8. Andante cantabile (Victor Ewald) 2.02 10 Var. 9. Fugato: Allegro (Alexander Winkler) 0.47 11 Var. 10. Finale. Allegro (Nikolai Sokolov) 1.18 PYOTR ILYICH TCHAIKOVSKY (1840–1893) Album for the Young Album für die Jugend · Album pour la jeunesse 12 Russian Song 1.00 Russisches Lied · Mélodie russe p2 IGOR STRAVINSKY (1882–1971) 13 Concertino 6.59 ALFRED SCHNITTKE (1934–1998) 14 Canon in memoriam Igor Stravinsky 6.36 PYOTR ILYICH TCHAIKOVSKY Album for the Young Album für die Jugend · Album pour la jeunesse 15 Old French Song 1.52 Altfranzösisches Lied · Mélodie antique française ONYX4090_cd-a-bklt v8_. 31/01/2012 16:49 Page 3 16 Mama 1.32 17 The Hobby Horse 0.33 Der kleine Reiter · Le petit cavalier 18 March of the Wooden Soldiers 0.57 Marsch der Holzsoldaten · Marche des soldats de bois 19 The Sick Doll 1.51 Die kranke Puppe · La poupée malade 20 The Doll’s Funeral 1.47 Begräbnis der Puppe · Enterrement de la poupée 21 The Witch 0.31 Die Hexe · La sorcière 22 Sweet Dreams 1.58 Süße Träumerei · Douce rêverie 23 Kamarinskaya (folk song) 1.17 Volkslied · Chanson populaire p3 PYOTR ILYICH TCHAIKOVSKY String Quartet no.1 in D op.11 Streichquartett Nr. -

Digital Concert Hall

Digital Concert Hall Streaming Partner of the Digital Concert Hall 21/22 season Where we play just for you Welcome to the Digital Concert Hall The Berliner Philharmoniker and chief The coming season also promises reward- conductor Kirill Petrenko welcome you to ing discoveries, including music by unjustly the 2021/22 season! Full of anticipation at forgotten composers from the first third the prospect of intensive musical encoun- of the 20th century. Rued Langgaard and ters with esteemed guests and fascinat- Leone Sinigaglia belong to the “Lost ing discoveries – but especially with you. Generation” that forms a connecting link Austro-German music from the Classi- between late Romanticism and the music cal period to late Romanticism is one facet that followed the Second World War. of Kirill Petrenko’s artistic collaboration In addition to rediscoveries, the with the orchestra. He continues this pro- season offers encounters with the latest grammatic course with works by Mozart, contemporary music. World premieres by Beethoven, Schubert, Mendelssohn, Olga Neuwirth and Erkki-Sven Tüür reflect Brahms and Strauss. Long-time compan- our diverse musical environment. Artist ions like Herbert Blomstedt, Sir John Eliot in Residence Patricia Kopatchinskaja is Gardiner, Janine Jansen and Sir András also one of the most exciting artists of our Schiff also devote themselves to this core time. The violinist has the ability to capti- repertoire. Semyon Bychkov, Zubin Mehta vate her audiences, even in challenging and Gustavo Dudamel will each conduct works, with enthusiastic playing, technical a Mahler symphony, and Philippe Jordan brilliance and insatiable curiosity. returns to the Berliner Philharmoniker Numerous debuts will arouse your after a long absence. -

Karnavi Ius Jurgis Karnavičius Jurgis Karnavičius (1884–1941)

JURGIS KARNAVI IUS JURGIS KARNAVIČIUS JURGIS KARNAVIČIUS (1884–1941) String Quartet No. 3, Op. 10 (1922) 33:13 I. Andante 8:00 2 II. Allegro 11:41 3 III. Lento tranquillo 13:32 String Quartet No. 4 (1925) 28:43 4 I. Moderato commodo 11:12 5 II. Andante 8:04 6 III. Allegro animato 9:27 World première recordings VILNIUS STRING QUARTET DALIA KUZNECOVAITĖ, 1st violin ARTŪRAS ŠILALĖ, 2nd violin KRISTINA ANUSEVIČIŪTĖ, viola DEIVIDAS DUMČIUS, cello 3 Epoch-unveiling music This album revives Jurgis Karnavičius’ (1884–1941) chamber music after many years of oblivion. It features the last two of his four string quartets, written in 1913–1925 while he was still living in St. Petersburg. Due to the turns and twists of the composer’s life these magnificent 20th-century chamber music opuses were performed extremely rarely after his death, thus the more pleasant discovery awaits all who will listen to these recordings. The Vilnius String Quartet has proceeded with a meaningful initiative to discover and resurrect those pages of Lithuanian quartet music that allow a broader view of Lithuanian music and testify to the internationality of our musical culture and connections with global music communities in momentous moments of the development of both Lithuanian and European music. In early stages of the 20th-century, not only Lithuanian national art, but also the concept of contemporary music and the ideas of international cooperation of musicians were formed on a global scale. Jurgis Karnavičius is a significant figure in Lithuanian music not only as a composer, having produced the first Lithuanian opera of the independence period – Gražina (based on a poem by Adam Mickiewicz) in 1933, but also as a personality, active in the orbit of the international community of contemporary musicians. -

Rep Decks™ Created by Kenneth Amis U.S.A

™ ANSWER KEY Piano Concerto in G Das Lied von der Symphony No.8, major Erde Op.65 2 6 1. Allegramente --- 3. Von der Jugend 2. Allegretto --- } Maurice Ravel, 1875– = Gustav Mahler, 1860– { Dmitri Shostakovich, 1937, France } 1911, Bohemia 1906–1975, Russia Symphony No.4 in F (Austrian The Nutcracker Suite, minor, Op.36 Empire/Czech Op.71a ; TH 35 3. Scherzo. Pizzicato Republic) 7 2e(6). Chinese Dance 3 Flute 1 ostinato Flutes Fountains of Rome { Pyotr Ilyich } 1. The Fountain of Pyotr Ilyich J Tchaikovsky, 1840– Tchaikovsky, 1840– Valle Giulia Bassoon 1 1893, Russia } 1893, Russia Ottorino Respighi, Semiramide Suor Angelic 1879–1936, Italy 8 Overture 4 Violin 1 Giacomo Puccini, --- Symphony No.5, { Gioacchino Rossini, } 1858–1924, Italy Op.67 1792–1868, Italy Pierrot Lunaire, Q 4. Allegro Dances of Galánta --- 9 Op.21 } Ludwig van Zoltán Kodály, 1882– Oboe 2 5 { 18. Der Mondfleck --- Beethoven, 1770– 1967, Hungary } Arnold Schoenberg, 1827, Germany Scheherazade, Op.35 1874–1951, Austria Karelia Suite, Op.11 4. Festival at Baghdad = Lieutenant Kijé K 3. Alla marcia Nikolai Rimsky- Flutes Flutes { Symphonic Suite, } Jean Sibelius, 1865– Korsakov, 1844–1908, Op.60 1957, Finland Russia 6 4. Troika --- The Valkyries WWV Mother Goose Suite, } Sergei Prokofiev, 86B M.60 1891–1953, Ukraine A Act 3, Scene 3 “Magic 3. Little Ugly Girl, Harps J (Russian Empire) } Fire Music” Empress of the --- Carnival Overture, Richard Wagner, { Pagodas Op.92 1813–1883, Germany Maurice Ravel, 1875– Antonín Dvořák, Symphony No.9, 1937, France 7 1841–1904, Bohemia Flutes Op.125 The Stars and Stripes } (Austrian 2 4. -

Audition Repertoire, Please Contact the Music Department at 812.941.2655 Or by E-Mail at AUDITION REQUIREMENTS for VARIOUS DEGREE CONCENTRATIONS

1 AUDITION GUIDE AND SUGGESTED REPERTOIRE 1 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS AUDITION REQUIREMENTS AND GUIDE . 3 SUGGESTED REPERTOIRE Piano/Keyboard . 5 STRINGS Violin . 6 Viola . 7 Cello . 8 String Bass . 10 WOODWINDS Flute . 12 Oboe . 13 Bassoon . 14 Clarinet . 15 Alto Saxophone . 16 Tenor Saxophone . 17 BRASS Trumpet/Cornet . 18 Horn . 19 Trombone . 20 Euphonium/Baritone . 21 Tuba/Sousaphone . 21 PERCUSSION Drum Set . 23 Xylophone-Marimba-Vibraphone . 23 Snare Drum . 24 Timpani . 26 Multiple Percussion . 26 Multi-Tenor . 27 VOICE Female Voice . 28 Male Voice . 30 Guitar . 33 2 3 The repertoire lists which follow should be used as a guide when choosing audition selections. There are no required selections. However, the following lists illustrate Students wishing to pursue the Instrumental or Vocal Performancethe genres, styles, degrees and difficulty are strongly levels encouraged of music that to adhereis typically closely expected to the of repertoire a student suggestionspursuing a music in this degree. list. Students pursuing the Sound Engineering, Music Business and Music Composition degrees may select repertoire that is slightly less demanding, but should select compositions that are similar to the selections on this list. If you have [email protected] questions about. this list or whether or not a specific piece is acceptable audition repertoire, please contact the Music Department at 812.941.2655 or by e-mail at AUDITION REQUIREMENTS FOR VARIOUS DEGREE CONCENTRATIONS All students applying for admission to the Music Department must complete a performance audition regardless of the student’s intended degree concentration. However, the performance standards and appropriaterequirements audition do vary repertoire.depending on which concentration the student intends to pursue. -

Sergei Prokofiev

Sergei Prokofiev Sergei Sergeyevich Prokofiev (/prɵˈkɒfiɛv/; Russian: Сергей Сергеевич Прокофьев, tr. Sergej Sergeevič Prokof'ev; April 27, 1891 [O.S. 15 April];– March 5, 1953) was a Russian composer, pianist and conductor. As the creator of acknowledged masterpieces across numerous musical genres, he is regarded as one of the major composers of the 20th century. His works include such widely heard works as the March from The Love for Three Oranges, the suite Lieutenant Kijé, the ballet Romeo and Juliet – from which "Dance of the Knights" is taken – and Peter and the Wolf. Of the established forms and genres in which he worked, he created – excluding juvenilia – seven completed operas, seven symphonies, eight ballets, five piano concertos, two violin concertos, a cello concerto, and nine completed piano sonatas. A graduate of the St Petersburg Conservatory, Prokofiev initially made his name as an iconoclastic composer-pianist, achieving notoriety with a series of ferociously dissonant and virtuosic works for his instrument, including his first two piano concertos. In 1915 Prokofiev made a decisive break from the standard composer-pianist category with his orchestral Scythian Suite, compiled from music originally composed for a ballet commissioned by Sergei Diaghilev of the Ballets Russes. Diaghilev commissioned three further ballets from Prokofiev – Chout, Le pas d'acier and The Prodigal Son – which at the time of their original production all caused a sensation among both critics and colleagues. Prokofiev's greatest interest, however, was opera, and he composed several works in that genre, including The Gambler and The Fiery Angel. Prokofiev's one operatic success during his lifetime was The Love for Three Oranges, composed for the Chicago Opera and subsequently performed over the following decade in Europe and Russia. -

Sergei Prokofiev's Children's Pieces, Op. 65: a Comprehensive Approach

Klein SpringerPlus 2014, 3:23 http://www.springerplus.com/content/3/1/23 a SpringerOpen Journal RESEARCH Open Access Sergei Prokofiev’s Children’s Pieces, Op. 65: a comprehensive approach to learning about a composer and his works: biography, style, form and analysis Peter Daniel Klein Abstract This article is written for the benefit of piano teachers and students, but can be of benefit to any music teacher or student. It is a case study using Prokofiev’s lesser known pedagogical work for the piano, which serves as an example of information gathering to apply toward a more effective method of instruction, which requires the teacher and student to exhaustively examine both composer and music in order to exact a more artistic, accurate performance. Much of the interpretation is based on Prokofiev’s own thoughts as expressed in his personal memoirs and from his most distinguished music critics, many of whom were his peers during his lifetime, while some is taken from common sources, which are readily available to teacher and student. It is my belief that it is possible to divine extraordinary interpretations, information and outcomes from common sources. As the student and teacher gather information, it can be used to determine what should be included in a performance based not only on the composer’s explicit directions, but also on implicit information that could lead to an inspired, original interpretation. It is written with the belief that music is more than the dots and lines on the page and that teaching and learning must be approached with that in mind. -

The Classical Station, WCPE 1 Start Runs Composer Title Performerslib # Label Cat

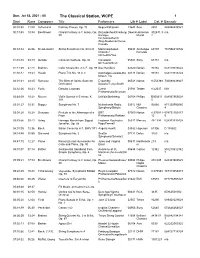

Sun, Jul 18, 2021 - 00 The Classical Station, WCPE 1 Start Runs Composer Title PerformersLIb # Label Cat. # Barcode 00:01:30 11:00 Schumann Fantasy Pieces, Op. 73 Segev/Pohjonen 13643 Avie 2389 822252238921 00:13:4518:34 Beethoven Choral Fantasy in C minor, Op. Bezuidenhout/Freiburg DownloadHarmonia 902431.3 n/a 80 Baroque Mundi 2 Orchestra/Zurich Zing-Akademie/Heras- Casado 00:33:34 26:06 Mendelssohn String Symphony No. 08 in D Metamorphosen 05480 Archetype 60107 701556010726 Chamber Records Orchestra/Yoo 01:01:1009:19 Dvorak Carnival Overture, Op. 92 Cleveland 05021 Sony 63151 n/a Orchestra/Szell 01:11:2927:48 Brahms Cello Sonata No. 2 in F, Op. 99 Diaz/Sanders 02520 Dorian 90165 053479016522 01:40:47 19:24 Haydn Piano Trio No. 43 in C Kalichstein-Laredo-Ro 02473 Dorian 90164 053479016423 binson Trio 02:01:4129:45 Rameau The Birth of Osiris (Suite for Ensemble 06541 Naxos 8.553388 730099438827 Orchestra) Savaria/Terey-Smith 02:32:26 10:43 Fucik Danube Legends Czech 01781 Teldec 8.42337 N/A Philharmonic/Neuman 02:44:0915:48 Mozart Violin Sonata in E minor, K. Uchida/Steinberg 04768 Philips B000411 028947565628 304 5 03:01:27 35:31 Dopper Symphony No. 7 Netherlands Radio 03512 NM 92060 871330992060 Symphony/Bakels Classics 4 03:38:2810:28 Debussy Prelude to the Afternoon of a BRT 07909 Naxos 8.570011- 074731300117 Faun Philharmonic/Rahbari 12 0 03:49:56 09:43 Grieg Homage March from Sigurd Eastman Rochester 05011 Mercury 434 394 028943439428 Jorsalfar, Op. 56 Pops/Fennell 04:01:0912:36 Bach Italian Concerto in F, BWV 971 Angela Hewitt 03592 Hyperion 67306 D 138602 04:14:4530:55 Diamond Symphony No.