Downloaded From: Usage Rights: Creative Commons: Attribution-Noncommercial-No Deriva- Tive Works 4.0

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rachmaninoff's Early Piano Works and the Traces of Chopin's Influence

Rachmaninoff’s Early Piano works and the Traces of Chopin’s Influence: The Morceaux de Fantaisie, Op.3 & The Moments Musicaux, Op.16 A document submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in the Division of Keyboard Studies of the College-Conservatory of Music by Sanghie Lee P.D., Indiana University, 2011 B.M., M.M., Yonsei University, Korea, 2007 Committee Chair: Jonathan Kregor, Ph.D. Abstract This document examines two of Sergei Rachmaninoff’s early piano works, Morceaux de Fantaisie, Op.3 (1892) and Moments Musicaux, Opus 16 (1896), as they relate to the piano works of Frédéric Chopin. The five short pieces that comprise Morceaux de Fantaisie and the six Moments Musicaux are reminiscent of many of Chopin’s piano works; even as the sets broadly build on his character genres such as the nocturne, barcarolle, etude, prelude, waltz, and berceuse, they also frequently are modeled on or reference specific Chopin pieces. This document identifies how Rachmaninoff’s sets specifically and generally show the influence of Chopin’s style and works, while exploring how Rachmaninoff used Chopin’s models to create and present his unique compositional identity. Through this investigation, performers can better understand Chopin’s influence on Rachmaninoff’s piano works, and therefore improve their interpretations of his music. ii Copyright © 2018 by Sanghie Lee All rights reserved iii Acknowledgements I cannot express my heartfelt gratitude enough to my dear teacher James Tocco, who gave me devoted guidance and inspirational teaching for years. -

Seattle Symphony February 2018 Encore Arts Seattle

FEBRUARY 2018 LUDOVIC MORLOT, MUSIC DIRECTOR LISA FISCHER & G R A N D BATON CELEBRATE ASIA IT TAKES AN ORCHESTRA COMMISSIONS &PREMIERES CONTENTS EAP full-page template.indd 1 12/22/17 1:03 PM CONTENTS FEBRUARY 2018 4 / CALENDAR 6 / THE SYMPHONY 10 / NEWS FEATURES 12 / IT TAKES AN ORCHESTRA 14 / THE ESSENTIALS OF LIFE CONCERTS 15 / February 1–3 RACHMANINOV SYMPHONY NO. 3 18 / February 2 JOSHUA BELL IN RECITAL 20 / February 8 & 10 MORLOT CONDUCTS STRAUSS 24 / February 11 CELEBRATE ASIA 28 / February 13 & 14 LA LA LAND IN CONCERT WITH THE SEATTLE SYMPHONY 30 / February 16–18 JUST A KISS AWAY! LISA FISCHER & GRAND BATON WITH THE SEATTLE SYMPHONY 15 / VILDE FRANG 33 / February 23 & 24 Photo courtesyPhoto of the artist VIVALDI GLORIA 46 / GUIDE TO THE SEATTLE SYMPHONY 47 / THE LIS(Z)T 24 / NISHAT KHAN 28 / LA LA LAND Photo: Dale Robinette Dale Photo: Photo courtesyPhoto of the artist ON THE COVER: Lisa Fischer (p. 30) by Djeneba Aduayom COVER DESIGN: Jadzia Parker EDITOR: Heidi Staub © 2018 Seattle Symphony. All rights reserved. No portion of this work may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means without written permission from the Seattle Symphony. All programs and artists are subject to change. encoremediagroup.com/programs 3 ON THE DIAL: Tune in to February Classical KING FM 98.1 every & March Wednesday at 8pm for a Seattle Symphony spotlight and CALENDAR the first Friday of every month at 9pm for concert broadcasts. SUNDAY MONDAY TUESDAY WEDNESDAY THURSDAY FRIDAY SATURDAY ■ FEBRUARY 12pm Rachmaninov 8pm Symphony No. -

EAST-CENTRAL EUROPEAN & BALKAN SYMPHONIES from The

EAST-CENTRAL EUROPEAN & BALKAN SYMPHONIES From the 19th Century To the Present A Discography Of CDs And LPs Prepared by Michael Herman Composers K-P MILOSLAV KABELÁČ (1908-1979, CZECH) Born in Prague. He studied composition at the Prague Conservatory under Karel Boleslav Jirák and conducting under Pavel Dedeček and at its Master School he studied the piano under Vilem Kurz. He then worked for Radio Prague as a conductor and one of its first music directors before becoming a professor of the Prague Conservatoy where he served for many years. He produced an extensive catalogue of orchestral, chamber, instrumental, vocal and choral works. Symphony No. 1 in D for Strings and Percussion, Op. 11 (1941–2) Marko Ivanovič/Prague Radio Symphony Orchestra ( + Symphonies Nos. 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7 and 8) SUPRAPHON SU42022 (4 CDs) (2016) Symphony No. 2 in C for Large Orchestra, Op. 15 (1942–6) Marko Ivanovič/Prague Radio Symphony Orchestra ( + Symphonies Nos. 1, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7 and 8) SUPRAPHON SU42022 (4 CDs) (2016) Symphony No. 3 in F major for Organ, Brass and Timpani, Op. 33 (1948-57) Marko Ivanovič//Prague Radio Symphony Orchestra ( + Symphonies Nos. 1, 2, 4, 5, 6, 7 and 8) SUPRAPHON SU42022 (4 CDs) (2016) Libor Pešek/Alena Veselá(organ)/Brass Harmonia ( + Kopelent: Il Canto Deli Augei and Fišer: 2 Piano Concerto) SUPRAPHON 1110 4144 (LP) (1988) Symphony No. 4 in A major, Op. 36 "Chamber" (1954-8) Marko Ivanovic/Czech Chamber Philharmonic Orchestra, Pardubice ( + Martin·: Oboe Concerto and Beethoven: Symphony No. 1) ARCO DIVA UP 0123 - 2 131 (2009) Marko Ivanovič//Prague Radio Symphony Orchestra ( + Symphonies Nos. -

Op. 68 Alexander Scriabin

Analysis of Scriabin’s Sonata No. 9 (“Black Mass”), Op. 68 Alexander Scriabin (1872-1915) was a Russian composer and pianist. An early modern composer, Scriabin’s inventiveness and controversial techniques, inspired by mysticism, synesthesia, and theology, contributed greatly to redefining Russian piano music and the modern musical era as a whole. Scriabin studied at the Moscow Conservatory with peers Anton Arensky, Sergei Taneyev, and Vasily Safonov. His ten piano sonatas are considered some of his greatest masterpieces; the first, Piano Sonata No. 1 In F Minor, was composed during his conservatory years. His Sonata No. 9 (“Black Mass”), Op. 68 was composed in 1912-13 and, more than any other sonata, encapsulates Scriabin’s philosophical and mystical related influences. Sonata No. 9 (“Black Mass”), Op. 68 is a single movement and lasts about 8-10 minutes. Despite the one movement structure, there are eight large tempo markings throughout the piece that imply a sense of slight division. They are: Moderato Quasi Andante (pg. 1), Molto Meno Vivo (pg. 7), Allegro (pg. 10), Allegro Molto (pg. 13), Alla Marcia (pg. 14), Allegro (p. 15), Presto (pg. 16), and Tempo I (pg. 16). As was common in Scriabin’s later works, the piece is extremely chromatic and atonal. Many of its recurring themes center around the extremely dissonant interval of a minor ninth1, and features several transformations of its opening theme, usually increasing in complexity in each of its restatements. Further, a common Scriabin quality involves his use of 1 Wise, H. Harold, “The relationship of pitch sets to formal structure in the last six piano sonatas of Scriabin," UR Research 1987, p. -

ONYX4090 Cd-A-Bklt V8 . 31/01/2012 16:49 Page 1 Page 16:49 31/01/2012 V8

ONYX4090_cd-a-bklt v8_. 31/01/2012 16:49 Page 1 p1 1 ONYX4090_cd-a-bklt v8_. 31/01/2012 16:49 Page 2 Variations on a Russian folk song for string quartet (1898, by various composers) Variationen über ein russisches Volkslied Variations sur un thème populaire russe 1 Theme. Adagio 0.56 2 Var. 1. Allegretto (Nikolai Artsybuschev) 0.40 3 Var. 2. Allegretto (Alexander Scriabin) 0.52 4 Var. 3. Andantino (Alexander Glazunov) 1.25 5 Var. 4. Allegro (Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov) 0.50 6 Var. 5. Canon. Adagio (Anatoly Lyadov) 1.19 7 Var. 6. Allegretto (Jazeps Vitols) 1.00 8 Var. 7. Allegro (Felix Blumenfeld) 0.58 9 Var. 8. Andante cantabile (Victor Ewald) 2.02 10 Var. 9. Fugato: Allegro (Alexander Winkler) 0.47 11 Var. 10. Finale. Allegro (Nikolai Sokolov) 1.18 PYOTR ILYICH TCHAIKOVSKY (1840–1893) Album for the Young Album für die Jugend · Album pour la jeunesse 12 Russian Song 1.00 Russisches Lied · Mélodie russe p2 IGOR STRAVINSKY (1882–1971) 13 Concertino 6.59 ALFRED SCHNITTKE (1934–1998) 14 Canon in memoriam Igor Stravinsky 6.36 PYOTR ILYICH TCHAIKOVSKY Album for the Young Album für die Jugend · Album pour la jeunesse 15 Old French Song 1.52 Altfranzösisches Lied · Mélodie antique française ONYX4090_cd-a-bklt v8_. 31/01/2012 16:49 Page 3 16 Mama 1.32 17 The Hobby Horse 0.33 Der kleine Reiter · Le petit cavalier 18 March of the Wooden Soldiers 0.57 Marsch der Holzsoldaten · Marche des soldats de bois 19 The Sick Doll 1.51 Die kranke Puppe · La poupée malade 20 The Doll’s Funeral 1.47 Begräbnis der Puppe · Enterrement de la poupée 21 The Witch 0.31 Die Hexe · La sorcière 22 Sweet Dreams 1.58 Süße Träumerei · Douce rêverie 23 Kamarinskaya (folk song) 1.17 Volkslied · Chanson populaire p3 PYOTR ILYICH TCHAIKOVSKY String Quartet no.1 in D op.11 Streichquartett Nr. -

Peter Tchaikovsky Symphony No. 4 in F Minor, Op. 36

PROGRAM NOTES by Phillip Huscher Peter Tchaikovsky Born May 7, 1840, Viatka, Russia. Died November 18, 1893, Saint Petersburg, Russia. Symphony No. 4 in F Minor, Op. 36 Tchaikovsky began this symphony in May 1877 and completed it on January 19, 1878. The first performance was given in Moscow on March 4, 1878. The score calls for two flutes and piccolo, two oboes, two clarinets, two bassoons, four horns, two trumpets, three trombones and tuba, timpani, triangle, cymbals, bass drum, and strings. Performance time is approximately forty-four minutes. The Chicago Symphony Orchestra’s first subscription concert performances of Tchaikovsky’s Fourth Symphony were given at the Auditorium Theatre on November 3 and 4, 1899, with Theodore Thomas conducting. Our most recent subscription concert performance was given at Orchestra Hall on November 10, 2006, with Ludovic Morlot conducting. The Orchestra first performed this symphony at the Ravinia Festival on July 17, 1936, with Willem van Hoogstraten conducting, and most recently on July 31, 1999, with Christoph Eschenbach conducting. The Chicago Symphony Orchestra recorded Tchaikovsky’s Fourth Symphony under Rafael Kubelík in 1951 for Mercury, under Sir Georg Solti for London in 1984, under Claudio Abbado for CBS in 1988, and under Daniel Barenboim for Teldec in 1997. Tchaikovsky was at work on his Fourth Symphony when he received a letter from Antonina Milyukova claiming to be a former student of his and declaring that she was madly in love with him. Tchaikovsky had just read Pushkin’s Eugene Onegin, hoping to find an opera subject, and he saw fateful parallels between Antonina and Pushkin’s heroine, Tatiana. -

The Fourteenth Season: Russian Reflections July 15–August 6, 2016 David Finckel and Wu Han, Artistic Directors Experience the Soothing Melody STAY with US

The Fourteenth Season: Russian Reflections July 15–August 6, 2016 David Finckel and Wu Han, Artistic Directors Experience the soothing melody STAY WITH US Spacious modern comfortable rooms, complimentary Wi-Fi, 24-hour room service, fitness room and a large pool. Just two miles from Stanford. BOOK EVENT MEETING SPACE FOR 10 TO 700 GUESTS. CALL TO BOOK YOUR STAY TODAY: 650-857-0787 CABANAPALOALTO.COM DINE IN STYLE Chef Francis Ramirez’ cuisine centers around sourcing quality seasonal ingredients to create delectable dishes combining French techniques with a California flare! TRY OUR CHAMPAGNE SUNDAY BRUNCH RESERVATIONS: 650-628-0145 4290 EL CAMINO REAL PALO ALTO CALIFORNIA 94306 Music@Menlo Russian Reflections the fourteenth season July 15–August 6, 2016 D AVID FINCKEL AND WU HAN, ARTISTIC DIRECTORS Contents 2 Season Dedication 3 A Message from the Artistic Directors 4 Welcome from the Executive Director 4 Board, Administration, and Mission Statement 5 R ussian Reflections Program Overview 6 E ssay: “Natasha’s Dance: The Myth of Exotic Russia” by Orlando Figes 10 Encounters I–III 13 Concert Programs I–VII 43 Carte Blanche Concerts I–IV 58 Chamber Music Institute 60 Prelude Performances 67 Koret Young Performers Concerts 70 Master Classes 71 Café Conversations 72 2016 Visual Artist: Andrei Petrov 73 Music@Menlo LIVE 74 2016–2017 Winter Series 76 Artist and Faculty Biographies A dance lesson in the main hall of the Smolny Institute, St. Petersburg. Russian photographer, twentieth century. Private collection/Calmann and King Ltd./Bridgeman Images 88 Internship Program 90 Glossary 94 Join Music@Menlo 96 Acknowledgments 101 Ticket and Performance Information 103 Map and Directions 104 Calendar www.musicatmenlo.org 1 2016 Season Dedication Music@Menlo’s fourteenth season is dedicated to the following individuals and organizations that share the festival’s vision and whose tremendous support continues to make the realization of Music@Menlo’s mission possible. -

Digital Concert Hall

Digital Concert Hall Streaming Partner of the Digital Concert Hall 21/22 season Where we play just for you Welcome to the Digital Concert Hall The Berliner Philharmoniker and chief The coming season also promises reward- conductor Kirill Petrenko welcome you to ing discoveries, including music by unjustly the 2021/22 season! Full of anticipation at forgotten composers from the first third the prospect of intensive musical encoun- of the 20th century. Rued Langgaard and ters with esteemed guests and fascinat- Leone Sinigaglia belong to the “Lost ing discoveries – but especially with you. Generation” that forms a connecting link Austro-German music from the Classi- between late Romanticism and the music cal period to late Romanticism is one facet that followed the Second World War. of Kirill Petrenko’s artistic collaboration In addition to rediscoveries, the with the orchestra. He continues this pro- season offers encounters with the latest grammatic course with works by Mozart, contemporary music. World premieres by Beethoven, Schubert, Mendelssohn, Olga Neuwirth and Erkki-Sven Tüür reflect Brahms and Strauss. Long-time compan- our diverse musical environment. Artist ions like Herbert Blomstedt, Sir John Eliot in Residence Patricia Kopatchinskaja is Gardiner, Janine Jansen and Sir András also one of the most exciting artists of our Schiff also devote themselves to this core time. The violinist has the ability to capti- repertoire. Semyon Bychkov, Zubin Mehta vate her audiences, even in challenging and Gustavo Dudamel will each conduct works, with enthusiastic playing, technical a Mahler symphony, and Philippe Jordan brilliance and insatiable curiosity. returns to the Berliner Philharmoniker Numerous debuts will arouse your after a long absence. -

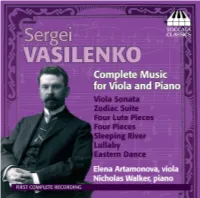

Toccata Classics TOCC 0127 Notes

SERGEI VASILENKO AND THE VIOLA by Elena Artamonova The viola is occasionally referred to as ‘the Cinderella of instruments’ – and, indeed, it used to take a fairy godmother of a player to allow this particular Cinderella to go to the ball; the example usually cited in the liberation of the viola in a solo role is the British violist Lionel Tertis. Another musician to pay the instrument a similar honour – as a composer rather than a player – was the Russian Sergei Vasilenko (1872–1956), all of whose known compositions for viola, published and unpublished, are to be heard on this CD, the fruit of my investigations in libraries and archives in Moscow and London. None is well known; some are not even included in any of the published catalogues of Vasilenko’s music. Only the Sonata was recorded previously, first in the 1960s by Georgy Bezrukov, viola, and Anatoly Spivak, piano,1 and again in 2007 by Igor Fedotov, viola, and Leonid Vechkhayzer, piano;2 the other compositions receive their first recordings here. Sergei Nikiforovich Vasilenko had a long and distinguished career as composer, conductor and pedagogue in the first half of the twentieth century. He was born in Moscow on 30 March 1872 into an aristocratic family, whose inner circle of friends consisted of the leading writers and artists of the time, but his interest in music was rather capricious in his early childhood: he started to play piano from the age of six only to give it up a year later, although he eventually resumed his lessons. In his mid-teens, after two years of tuition on the clarinet, he likewise gave it up in favour of the oboe. -

The Development of the Russian Piano Concerto in the Nineteenth Century Jeremy Paul Norris Doctor of Philosophy Department of Mu

The Development of the Russian Piano Concerto in the Nineteenth Century Jeremy Paul Norris Doctor of Philosophy Department of Music 1988 December The Development of the Russian Piano Concerto in the Nineteenth Century Jeremy Paul Norris The Russian piano concerto could not have had more inauspicious beginnings. Unlike the symphonic poem (and, indirectly, the symphony) - genres for which Glinka, the so-called 'Father of Russian Music', provided an invaluable model: 'Well? It's all in "Kamarinskaya", just as the whole oak is in the acorn' to quote Tchaikovsky - the Russian piano concerto had no such indigenous prototype. All that existed to inspire would-be concerto composers were a handful of inferior pot- pourris and variations for piano and orchestra and a negligible concerto by Villoing dating from the 1830s. Rubinstein's five con- certos certainly offered something more substantial, as Tchaikovsky acknowledged in his First Concerto, but by this time the century was approaching its final quarter. This absence of a prototype is reflected in all aspects of Russian concerto composition. Most Russian concertos lean perceptibly on the stylistic features of Western European composers and several can be justly accused of plagiarism. Furthermore, Russian composers faced formidable problems concerning the structural organization of their concertos, a factor which contributed to the inability of several, including Balakirev and Taneyev, to complete their works. Even Tchaikovsky encountered difficulties which he was not always able to overcome. The most successful Russian piano concertos of the nineteenth century, Tchaikovsky's No.1 in B flat minor, Rimsky-Korsakov's Concerto in C sharp minor and Balakirev's Concerto in E flat, returned ii to indigenous sources of inspiration: Russian folk song and Russian orthodox chant. -

Karnavi Ius Jurgis Karnavičius Jurgis Karnavičius (1884–1941)

JURGIS KARNAVI IUS JURGIS KARNAVIČIUS JURGIS KARNAVIČIUS (1884–1941) String Quartet No. 3, Op. 10 (1922) 33:13 I. Andante 8:00 2 II. Allegro 11:41 3 III. Lento tranquillo 13:32 String Quartet No. 4 (1925) 28:43 4 I. Moderato commodo 11:12 5 II. Andante 8:04 6 III. Allegro animato 9:27 World première recordings VILNIUS STRING QUARTET DALIA KUZNECOVAITĖ, 1st violin ARTŪRAS ŠILALĖ, 2nd violin KRISTINA ANUSEVIČIŪTĖ, viola DEIVIDAS DUMČIUS, cello 3 Epoch-unveiling music This album revives Jurgis Karnavičius’ (1884–1941) chamber music after many years of oblivion. It features the last two of his four string quartets, written in 1913–1925 while he was still living in St. Petersburg. Due to the turns and twists of the composer’s life these magnificent 20th-century chamber music opuses were performed extremely rarely after his death, thus the more pleasant discovery awaits all who will listen to these recordings. The Vilnius String Quartet has proceeded with a meaningful initiative to discover and resurrect those pages of Lithuanian quartet music that allow a broader view of Lithuanian music and testify to the internationality of our musical culture and connections with global music communities in momentous moments of the development of both Lithuanian and European music. In early stages of the 20th-century, not only Lithuanian national art, but also the concept of contemporary music and the ideas of international cooperation of musicians were formed on a global scale. Jurgis Karnavičius is a significant figure in Lithuanian music not only as a composer, having produced the first Lithuanian opera of the independence period – Gražina (based on a poem by Adam Mickiewicz) in 1933, but also as a personality, active in the orbit of the international community of contemporary musicians. -

Rep Decks™ Created by Kenneth Amis U.S.A

™ ANSWER KEY Piano Concerto in G Das Lied von der Symphony No.8, major Erde Op.65 2 6 1. Allegramente --- 3. Von der Jugend 2. Allegretto --- } Maurice Ravel, 1875– = Gustav Mahler, 1860– { Dmitri Shostakovich, 1937, France } 1911, Bohemia 1906–1975, Russia Symphony No.4 in F (Austrian The Nutcracker Suite, minor, Op.36 Empire/Czech Op.71a ; TH 35 3. Scherzo. Pizzicato Republic) 7 2e(6). Chinese Dance 3 Flute 1 ostinato Flutes Fountains of Rome { Pyotr Ilyich } 1. The Fountain of Pyotr Ilyich J Tchaikovsky, 1840– Tchaikovsky, 1840– Valle Giulia Bassoon 1 1893, Russia } 1893, Russia Ottorino Respighi, Semiramide Suor Angelic 1879–1936, Italy 8 Overture 4 Violin 1 Giacomo Puccini, --- Symphony No.5, { Gioacchino Rossini, } 1858–1924, Italy Op.67 1792–1868, Italy Pierrot Lunaire, Q 4. Allegro Dances of Galánta --- 9 Op.21 } Ludwig van Zoltán Kodály, 1882– Oboe 2 5 { 18. Der Mondfleck --- Beethoven, 1770– 1967, Hungary } Arnold Schoenberg, 1827, Germany Scheherazade, Op.35 1874–1951, Austria Karelia Suite, Op.11 4. Festival at Baghdad = Lieutenant Kijé K 3. Alla marcia Nikolai Rimsky- Flutes Flutes { Symphonic Suite, } Jean Sibelius, 1865– Korsakov, 1844–1908, Op.60 1957, Finland Russia 6 4. Troika --- The Valkyries WWV Mother Goose Suite, } Sergei Prokofiev, 86B M.60 1891–1953, Ukraine A Act 3, Scene 3 “Magic 3. Little Ugly Girl, Harps J (Russian Empire) } Fire Music” Empress of the --- Carnival Overture, Richard Wagner, { Pagodas Op.92 1813–1883, Germany Maurice Ravel, 1875– Antonín Dvořák, Symphony No.9, 1937, France 7 1841–1904, Bohemia Flutes Op.125 The Stars and Stripes } (Austrian 2 4.