Op. 68 Alexander Scriabin

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Music%2034.Syllabus

Music 34, Detailed Syllabus INTRODUCTION—January 24 (M) “Half-step over-saturation”—Richard Strauss Music: Salome (scene 1), Morgan 9 Additional reading: Richard Taruskin, The Oxford History of Western Music, vol. 4 (henceforth RT), (see Reader) 36-48 Musical vocabulary: Tristan progression, augmented chords, 9th chords, semitonal expansion/contraction, master array Recommended listening: more of Salome Recommended reading: Derrick Puffett, Richard Strauss Salome. Cambridge Opera Handbooks (Cambridge, New York: Cambridge University Press, 1989) No sections in first week UNIT 1—Jan. 26 (W); Jan. 31 (M) “Half-steplessness”—Debussy Music: Estampes, No. 2 (La Soiré dans Grenade), Morgan 1; “Nuages” from Three Nocturnes (Anthology), “Voiles” from Preludes I (Anthology) Reading: RT 69-83 Musical vocabulary: whole-tone scales, pentatonic scales, parallelism, whole-tone chord, pentatonic chords, center of gravity/symmetry Recommended listening: Three Noctures SECTIONS start UNIT 2—Feb. 2 (W); Feb. 7 (M) “Invariance”—Skryabin Music: Prelude, Op. 35, No. 3; Etude, Op. 56, No. 4, Prelude Op. 74, No. 3, Morgan 21-25. Reading: RT 197-227 Vocabulary: French6; altered chords; Skryabin6; tritone link; “Ecstasy chord,” “Mystic chord”, octatonicism (I) Recommended reading: Taruskin, “Scriabin and the Superhuman,” in Defining Russia Musically: Historical and Hermeneutical Essays (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1997), 308-359 Recommended listening: Poème d’extase; Alexander Krein, Sonata for Piano UNIT 3—Feb. 9 (W); Feb. 14 (M) “Grundgestalt”—Schoenberg I Music: Opus 16, No. 1, No. 5, Morgan 30-45. Reading: RT 321-337, 341-343; Simms: The Atonal Music of Arnold Schoenberg 1908-1923 (excerpt) Vocabulary: atonal triads, set theory, Grundgestalt, “Aschbeg” set, organicism, Klangfarben melodie Recommended reading: Móricz, “Anxiety, Abstraction, and Schoenberg’s Gestures of Fear,” in Essays in Honor of László Somfai on His 70th Birthday: Studies in the Sources and the Interpretation of Music, ed. -

Rachmaninoff's Early Piano Works and the Traces of Chopin's Influence

Rachmaninoff’s Early Piano works and the Traces of Chopin’s Influence: The Morceaux de Fantaisie, Op.3 & The Moments Musicaux, Op.16 A document submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in the Division of Keyboard Studies of the College-Conservatory of Music by Sanghie Lee P.D., Indiana University, 2011 B.M., M.M., Yonsei University, Korea, 2007 Committee Chair: Jonathan Kregor, Ph.D. Abstract This document examines two of Sergei Rachmaninoff’s early piano works, Morceaux de Fantaisie, Op.3 (1892) and Moments Musicaux, Opus 16 (1896), as they relate to the piano works of Frédéric Chopin. The five short pieces that comprise Morceaux de Fantaisie and the six Moments Musicaux are reminiscent of many of Chopin’s piano works; even as the sets broadly build on his character genres such as the nocturne, barcarolle, etude, prelude, waltz, and berceuse, they also frequently are modeled on or reference specific Chopin pieces. This document identifies how Rachmaninoff’s sets specifically and generally show the influence of Chopin’s style and works, while exploring how Rachmaninoff used Chopin’s models to create and present his unique compositional identity. Through this investigation, performers can better understand Chopin’s influence on Rachmaninoff’s piano works, and therefore improve their interpretations of his music. ii Copyright © 2018 by Sanghie Lee All rights reserved iii Acknowledgements I cannot express my heartfelt gratitude enough to my dear teacher James Tocco, who gave me devoted guidance and inspirational teaching for years. -

UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA Los Angeles

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Transcending Imagination; Or, An Approach to Music and Symbolism during the Russian Silver Age A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Musicology by Ryan Isao Rowen 2015 © Copyright by Ryan Isao Rowen 2015 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Transcending Imagination; Or, An Approach to Music and Symbolism during the Russian Silver Age by Ryan Isao Rowen Doctor of Philosophy in Musicology University of California, Los Angeles, 2015 Professor Mitchell Bryan Morris, Chair The Silver Age has long been considered one of the most vibrant artistic movements in Russian history. Due to sweeping changes that were occurring across Russia, culminating in the 1917 Revolution, the apocalyptic sentiments of the general populace caused many intellectuals and artists to turn towards esotericism and occult thought. With this, there was an increased interest in transcendentalism, and art was becoming much more abstract. The tenets of the Russian Symbolist movement epitomized this trend. Poets and philosophers, such as Vladimir Solovyov, Andrei Bely, and Vyacheslav Ivanov, theorized about the spiritual aspects of words and music. It was music, however, that was singled out as possessing transcendental properties. In recent decades, there has been a surge in scholarly work devoted to the transcendent strain in Russian Symbolism. The end of the Cold War has brought renewed interest in trying to understand such an enigmatic period in Russian culture. While much scholarship has been ii devoted to Symbolist poetry, there has been surprisingly very little work devoted to understanding how the soundscape of music works within the sphere of Symbolism. -

A Discussion of the Piano Sonata No. 2 in D Minor, Op

A DISCUSSION OF THE PIANO SONATA NO. 2 IN D MINOR, OP. 14, BY SERGEI PROKOFIEV A PAPER ACCOMPANYING A THREE CREDIT-HOUR CREATIVE PROJECT RECITAL SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE MASTER OF MUSIC BY QINYUAN LIN DR. ROBERT PALMER‐ ADVISOR BALL STATE UNIVERSITY MUNCIE, INDIANA JULY 2010 Preface The goal of this paper is to introduce the piece, provide historical background, and focus on the musical analysis of the sonata. The introduction of the piece will include a brief biography of Sergei Prokofiev and the circumstance in which the piece was composed. A general overview of the composition, performance, and perception of this piece will be discussed. The bulk of the paper will focus on the musical analysis of Piano Sonata No. 2 from my perspective as a performer of the piece. It will be broken into four sections, one each for the four movements in the sonata. In the discussion for each movement, I will analyze the forms used as well as required techniques and difficulties to be considered by the pianist. The conclusion will summarize the discussion. i Table of Contents Preface ________________________________________________________________ i Introduction ____________________________________________________________ 1 The First Movement: Allegro, ma non troppo __________________________________ 5 The Second Movement: Scherzo ____________________________________________ 9 The Third Movement: Andante ____________________________________________ 11 The Fourth Movement: Vivace ____________________________________________ 13 Conclusion ____________________________________________________________ 17 Bibliography __________________________________________________________ 18 ii Introduction Sergei Prokofiev was born in 1891 to parents Sergey and Mariya and grew up in comfortable circumstances. His mother, Mariya, had a feeling for the arts and gave the young Prokofiev his first piano lessons at the age of four. -

Function and Structure of Transitions in Sonata — Form Music of Mozart Robert Batt

Document généré le 1 oct. 2021 08:37 Canadian University Music Review Revue de musique des universités canadiennes --> Voir l’erratum concernant cet article Function and Structure of Transitions in Sonata — Form Music of Mozart Robert Batt Volume 9, numéro 1, 1988 URI : https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/1014927ar DOI : https://doi.org/10.7202/1014927ar Aller au sommaire du numéro Éditeur(s) Canadian University Music Society / Société de musique des universités canadiennes ISSN 0710-0353 (imprimé) 2291-2436 (numérique) Découvrir la revue Citer cet article Batt, R. (1988). Function and Structure of Transitions in Sonata — Form Music of Mozart. Canadian University Music Review / Revue de musique des universités canadiennes, 9(1), 157–201. https://doi.org/10.7202/1014927ar All Rights Reserved © Canadian University Music Society / Société de musique Ce document est protégé par la loi sur le droit d’auteur. L’utilisation des des universités canadiennes, 1988 services d’Érudit (y compris la reproduction) est assujettie à sa politique d’utilisation que vous pouvez consulter en ligne. https://apropos.erudit.org/fr/usagers/politique-dutilisation/ Cet article est diffusé et préservé par Érudit. Érudit est un consortium interuniversitaire sans but lucratif composé de l’Université de Montréal, l’Université Laval et l’Université du Québec à Montréal. Il a pour mission la promotion et la valorisation de la recherche. https://www.erudit.org/fr/ FUNCTION AND STRUCTURE OF TRANSITIONS IN SONATA-FORM MUSIC OF MOZART Robert Batt The transition, sometimes referred to as the bridge, is usually regarded as the section of sonata form responsible for modulating from the pri• mary to the secondary key as well as for effecting a structural contrast between the two thematic sections. -

Mystic Chord Harmonic and Light Transformations In

MYSTIC CHORD HARMONIC AND LIGHT TRANSFORMATIONS IN ALEXANDER SCRIABIN’S PROMETHEUS by TYLER MATTHEW SECOR A THESIS Presented to the School of Music and Dance and the Graduate School of the University of Oregon in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts September 2013 THESIS APPROVAL PAGE Student: Tyler Matthew Secor Title: Mystic Chord Harmonic and Light Transformations in Alexander Scriabin’s Prometheus This thesis has been accepted and approved in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Master of Arts degree in the School of Music and Dance by: Dr. Jack Boss Chair Dr. Stephen Rodgers Member Dr. Frank Diaz Member and Kimberly Andrews Espy Vice President for Research and Innovation Dean of the Graduate School Original approval signatures are on file with the University of Oregon Graduate School. Degree awarded September 2013 ii © 2013 Tyler Matthew Secor iii THESIS ABSTRACT Tyler Matthew Secor Master of Arts School of Music and Dance September 2013 Title: Mystic Chord Harmonic and Light Transformations in Alexander Scriabin’s Prometheus This thesis seeks to explore the voice leading parsimony, bass motion, and chromatic extensions present in Alexander Scriabin’s Prometheus. Voice leading will be explored using Neo-Riemannian type transformations followed by network diagrams to track the mystic chord movement throughout the symphony. Bass motion and chromatic extensions are explored by expanding the current notion of how the luce voices function in outlining and dictating the harmonic motion. Syneathesia -

Peter Tchaikovsky Symphony No. 4 in F Minor, Op. 36

PROGRAM NOTES by Phillip Huscher Peter Tchaikovsky Born May 7, 1840, Viatka, Russia. Died November 18, 1893, Saint Petersburg, Russia. Symphony No. 4 in F Minor, Op. 36 Tchaikovsky began this symphony in May 1877 and completed it on January 19, 1878. The first performance was given in Moscow on March 4, 1878. The score calls for two flutes and piccolo, two oboes, two clarinets, two bassoons, four horns, two trumpets, three trombones and tuba, timpani, triangle, cymbals, bass drum, and strings. Performance time is approximately forty-four minutes. The Chicago Symphony Orchestra’s first subscription concert performances of Tchaikovsky’s Fourth Symphony were given at the Auditorium Theatre on November 3 and 4, 1899, with Theodore Thomas conducting. Our most recent subscription concert performance was given at Orchestra Hall on November 10, 2006, with Ludovic Morlot conducting. The Orchestra first performed this symphony at the Ravinia Festival on July 17, 1936, with Willem van Hoogstraten conducting, and most recently on July 31, 1999, with Christoph Eschenbach conducting. The Chicago Symphony Orchestra recorded Tchaikovsky’s Fourth Symphony under Rafael Kubelík in 1951 for Mercury, under Sir Georg Solti for London in 1984, under Claudio Abbado for CBS in 1988, and under Daniel Barenboim for Teldec in 1997. Tchaikovsky was at work on his Fourth Symphony when he received a letter from Antonina Milyukova claiming to be a former student of his and declaring that she was madly in love with him. Tchaikovsky had just read Pushkin’s Eugene Onegin, hoping to find an opera subject, and he saw fateful parallels between Antonina and Pushkin’s heroine, Tatiana. -

CONCERTS// JAMES EHNES 2014 Summer Festival Artistic Director Illsley Ball Nordstrom Recital Hall at Benaroya Hall

CONCERTS// JAMES EHNES 2014 Summer Festival Artistic Director Illsley Ball Nordstrom Recital Hall at Benaroya Hall. TICKETS All programs and artists subject to change. (206) 283-8808 seattlechambermusic.org MONDAY, JULY 7 FRIDAY, JULY 11 All concerts feature 7:00 PM RECITAL 7:00 PM RECITAL a FREE 30 minute DAVID LANG BÉLA BARTÓK Pre-Concert Recital Mystery Sonatas selections from 44 Duos for Two Violins that begins at 7:00pm Augustin Hadelich James Ehnes, Amy Schwartz Moretti 8:00 PM CONCERT 8:00 PM CONCERT CAMILLE SAINT-SAËNS WOLFGANG AMADEUS MOZART Fantaisie in A Major for Violin and Harp, Op. 124 Quartet for Flute and Strings in D Major, K. 285 Augustin Hadelich, Valerie Muzzolini Gordon Lorna McGhee, Augustin Hadelich, Richard O’Neill, Ronald Thomas SERGEI RACHMANINOV Sonata in G minor for Cello and Piano, Op. 19 JOHANNES BRAHMS Robert deMaine, Jon Kimura Parker Quartet for Piano and Strings in G minor, Op. 25 Amy Schwartz Moretti, Cynthia Phelps, FRANZ SCHUBERT Robert deMaine, Jon Kimura Parker Octet in F Major for Strings and Winds, D. 803 James Ehnes, Amy Schwartz Moretti, IGOR STRAVINSKY Richard O’Neill, Efe Baltacıgil, Jordan Anderson, The Soldier’s Tale Anthony McGill, Stéphane Lévesque, Jeffrey Fair James Ehnes, Jordan Anderson, Anthony McGill, Stéphane Lévesque, Jens Lindemann, Ko-Ichiro Yamamoto, Michael Werner WEDNESDAY, JULY 9 7:00 PM RECITAL MONDAY, JULY 14 LUDWIG VAN BEETHOVEN 7:00 PM RECITAL String Quartet in C minor, Op. 18 No. 4 James Ehnes, Amy Schwartz Moretti, INTRODUCTION TO DEREK BERMEL'S Richard O’Neill, Robert deMaine PIANO TRIO 8:00 PM CONCERT 8:00 PM CONCERT IGOR STRAVINSKY FRANZ SCHUBERT Octet for Winds String Trio in B-flat Major, D. -

Ballet Notes the Seagull March 21 – 25, 2012

Ballet Notes The SeagUll March 21 – 25, 2012 Aleksandar Antonijevic and Sonia Rodriguez as Trigorin and Nina. Photo by Cylla von Tiedemann. Orchestra Violins Trumpets Benjamin Bowman Richard Sandals, Principal Concertmaster Mark Dharmaratnam Lynn KUo, Robert WeymoUth Assistant Concertmaster Trombones DominiqUe Laplante, David Archer, Principal Principal Second Violin Robert FergUson James Aylesworth David Pell, Bass Trombone Jennie Baccante Csaba Ko czó Tuba Sheldon Grabke Sasha Johnson, Principal Xiao Grabke • Nancy Kershaw Harp Sonia Klimasko-LeheniUk LUcie Parent, Principal Celia Franca, C.C., FoUnder Yakov Lerner Timpany George Crum, MUsic Director EmeritUs Jayne Maddison Michael Perry, Principal Ron Mah Karen Kain, C.C. Kevin Garland Aya Miyagawa Percussion Mark MazUr, Acting Artistic Director ExecUtive Director Wendy Rogers Filip Tomov Principal David Briskin Rex Harrington, O.C. Joanna Zabrowarna Kristofer Maddigan MUsic Director and Artist-in-Residence PaUl ZevenhUizen Orchestra Personnel Principal CondUctor Violas Manager and Music Magdalena Popa Lindsay Fischer Angela RUdden, Principal Administrator Principal Artistic Coach Artistic Director, • Theresa RUdolph Koczó, Jean Verch YOU dance / Ballet Master Assistant Principal Assistant Orchestra Valerie KUinka Peter Ottmann Mandy-Jayne Personnel Manager Johann Lotter Raymond Tizzard Senior Ballet Master Richardson Beverley Spotton Senior Ballet Mistress • Larry Toman Librarian LUcie Parent Aleksandar Antonijevic, GUillaUme Côté, Cellos Greta Hodgkinson, Jiˇrí Jelinek, Zdenek Konvalina*, -

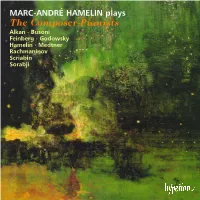

MARC-ANDRÉ HAMELIN Plays the Composer-Pianists Alkan

MARC-ANDRÉ HAMELIN plays The Composer-Pianists Alkan . Busoni Feinberg . Godowsky Hamelin . Medtner Rachmaninov Scriabin Sorabji HE RELATION between musical effect and the technical ‘encore’ repertoire; less convincingly as regards the latter half means necessary for its creation or recreation is apt to of a recital, which at one time might have been entirely Tbe one of opposites. The ‘Representation of Chaos’ with devoted to the type of confection indicated above. However, it which Haydn embarked on The Creation, for example, could can be said that the present offers the best of all liberal worlds, not have succeeded without a conspicuously well ordered in which deeply serious artists may leaven but not demean the compositional technique, nor could the percussion- and intellectual and spiritual weight of their mainstream reper- timpani-based anarchy of Nielsen’s Fourth and Fifth toire by restoring to public attention the full variety and zest of Symphonies or, indeed, the ‘controlled chance’ of more a once discredited milieu. In this connection the abstract recent, aleatory trends. A true chaos of means leads only to nature and importance of ‘pianism’ itself should be empha- incoherence, whereas an intended one of expressive ends may sized: for the serious performing artist the purely physical, be likened to the birth of a universe: explosive, precipitate, callisthenic dimension in Tausig, Rosenthal, Schulz-Evler, seemingly beyond all elemental control, and yet achieved with Scharwenka, Hoffman, Godowsky and others illumines the the pinprick accuracy of some infinitely magnified snowflake, nature of the instrument, and of the art itself, in myriad and defying our later scrutiny to find in it mere accident rather idiosyncratic ways. -

Sergei Taneyev Aaron Jay Kernis Sergei Rachmaninov

CONCERT #6 - Released JULY 29, 2021 SERGEI TANEYEV String Trio in D Major Allegro Scherzo Adagio ma non troppo Finale. Allegro molto—Più mosso Bejamin Beilman violin / Yura Lee viola / Bion Tsang cello AARON JAY KERNIS Before Sleep and Dreams Before Play Before Lullaby Lullaby Lights Before Sleep Before Sleep and Dreams Andrew Armstrong piano SERGEI RACHMANINOV Sonata for Cello and Piano in G minor, Op. 19 Lento—Allegro moderato Allegro scherzando Andante Allegro mosso Bion Tsang cello / Stewart Goodyear piano SERGEI TANEYEV chordal episodes. An open-air quality pervades, (1856–1915) offset by occasional forays into the minor. His wonted String Trio in D Major (1880) contrapuntal gifts mid-movement do not slavishly Most recent SCMS performance: Summer 2014 imitate Baroque fugal writing. Friend and erstwhile student of Tchaikovsky, Sergei Redolent of Mendelssohn’s all but patented “elfin” Taneyev earned a reputation as an especially gifted scherzos, the like-named movement occasionally pianist and a lesser one as a composer. Despite darkens into brief “night” thoughts. The second personal intellectual and stylistic differences vis à theme led by the viola provides a lovely dose of vis his mentor’s approach to musical composition, lyricism. A more forceful chordal mid-section recurs, Taneyev premiered Tchaikovsky’s second and suggesting a cross between scherzo and rondo. As third piano concertos. Keeping his compositional with the opening movement his Russian birthright is aspirations largely under wraps, Taneyev felt no clearly manifest, ideology notwithstanding. kinship with the nationalist composers known collectively as the “Mighty Five” or “Mighty Handful,” The ensuing Adagio—the emotional heart of the which may have cemented his relationship with piece—unfolds slowly, positing a sad opening theme Tchaikovsky, who was viewed with suspicion (and on a rising triad that moves to a lower repeated probably jealousy) by the uber-nationalist cabal. -

![Arxiv:1606.05833V3 [Math.HO] 26 Sep 2018 Developed by Mazzola [12, Part VII]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5722/arxiv-1606-05833v3-math-ho-26-sep-2018-developed-by-mazzola-12-part-vii-1285722.webp)

Arxiv:1606.05833V3 [Math.HO] 26 Sep 2018 Developed by Mazzola [12, Part VII]

CONTRAPUNTAL ASPECTS OF THE MYSTIC CHORD AND SCRIABIN'S PIANO SONATA NO. 5 OCTAVIO A. AGUST´IN-AQUINO AND GUERINO MAZZOLA Abstract. We present statistical evidence for the importance of the \mystic chord" in Scriabin's Piano Sonata No. 5, Op. 53, from a computational and mathematical counterpoint perspective. More specifically, we compute the effect sizes and χ2 tests with respect to the distributions of counterpoint symmetries in the Fux- ian, mystic, Ionian and representatives of the other three possible counterpoint worlds in two passages of the work, which provide ev- idence of a qualitative change between the Fuxian and the mystic world in the sonata. 1. Introduction A prominent chord in Alexander Scriabin's late work is the so-called \mystic chord" or \Prometheus chord", whose pc-set when the root is C is M = f0; 6; 10; 4; 9; 2g [7, p. 23]. It can be seen as a chain of thirds, and thus can be covered by an augmented triad followed by a diminished triad, together with a major triad followed by a minor triad (see Figure 1). This surely evidences the strong tonal ambiguity of the chord, which is also associated to the Impressionism in music during the late 19th and early 20th centuries in Europe [15]. The mystic chord can be seen as an extension of the French sixth, which is completely contained in a whole tone scale; the mystic chord also has this property safe for a \sensible" tone [3, p. 278]. As we will see, this is an important feature from the perspective of the mathematical counterpoint theory arXiv:1606.05833v3 [math.HO] 26 Sep 2018 developed by Mazzola [12, Part VII].