Mystic Chord Harmonic and Light Transformations In

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Music%2034.Syllabus

Music 34, Detailed Syllabus INTRODUCTION—January 24 (M) “Half-step over-saturation”—Richard Strauss Music: Salome (scene 1), Morgan 9 Additional reading: Richard Taruskin, The Oxford History of Western Music, vol. 4 (henceforth RT), (see Reader) 36-48 Musical vocabulary: Tristan progression, augmented chords, 9th chords, semitonal expansion/contraction, master array Recommended listening: more of Salome Recommended reading: Derrick Puffett, Richard Strauss Salome. Cambridge Opera Handbooks (Cambridge, New York: Cambridge University Press, 1989) No sections in first week UNIT 1—Jan. 26 (W); Jan. 31 (M) “Half-steplessness”—Debussy Music: Estampes, No. 2 (La Soiré dans Grenade), Morgan 1; “Nuages” from Three Nocturnes (Anthology), “Voiles” from Preludes I (Anthology) Reading: RT 69-83 Musical vocabulary: whole-tone scales, pentatonic scales, parallelism, whole-tone chord, pentatonic chords, center of gravity/symmetry Recommended listening: Three Noctures SECTIONS start UNIT 2—Feb. 2 (W); Feb. 7 (M) “Invariance”—Skryabin Music: Prelude, Op. 35, No. 3; Etude, Op. 56, No. 4, Prelude Op. 74, No. 3, Morgan 21-25. Reading: RT 197-227 Vocabulary: French6; altered chords; Skryabin6; tritone link; “Ecstasy chord,” “Mystic chord”, octatonicism (I) Recommended reading: Taruskin, “Scriabin and the Superhuman,” in Defining Russia Musically: Historical and Hermeneutical Essays (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1997), 308-359 Recommended listening: Poème d’extase; Alexander Krein, Sonata for Piano UNIT 3—Feb. 9 (W); Feb. 14 (M) “Grundgestalt”—Schoenberg I Music: Opus 16, No. 1, No. 5, Morgan 30-45. Reading: RT 321-337, 341-343; Simms: The Atonal Music of Arnold Schoenberg 1908-1923 (excerpt) Vocabulary: atonal triads, set theory, Grundgestalt, “Aschbeg” set, organicism, Klangfarben melodie Recommended reading: Móricz, “Anxiety, Abstraction, and Schoenberg’s Gestures of Fear,” in Essays in Honor of László Somfai on His 70th Birthday: Studies in the Sources and the Interpretation of Music, ed. -

Computational Methods for Tonality-Based Style Analysis of Classical Music Audio Recordings

Fakult¨at fur¨ Elektrotechnik und Informationstechnik Computational Methods for Tonality-Based Style Analysis of Classical Music Audio Recordings Christof Weiß geboren am 16.07.1986 in Regensburg Dissertation zur Erlangung des akademischen Grades Doktoringenieur (Dr.-Ing.) Angefertigt im: Fachgebiet Elektronische Medientechnik Institut fur¨ Medientechnik Fakult¨at fur¨ Elektrotechnik und Informationstechnik Gutachter: Prof. Dr.-Ing. Dr. rer. nat. h. c. mult. Karlheinz Brandenburg Prof. Dr. rer. nat. Meinard Muller¨ Prof. Dr. phil. Wolfgang Auhagen Tag der Einreichung: 25.11.2016 Tag der wissenschaftlichen Aussprache: 03.04.2017 urn:nbn:de:gbv:ilm1-2017000293 iii Acknowledgements This thesis could not exist without the help of many people. I am very grateful to everybody who supported me during the work on my PhD. First of all, I want to thank Prof. Karlheinz Brandenburg for supervising my thesis but also, for the opportunity to work within a great team and a nice working enviroment at Fraunhofer IDMT in Ilmenau. I also want to mention my colleagues of the Metadata department for having such a friendly atmosphere including motivating scientific discussions, musical activity, and more. In particular, I want to thank all members of the Semantic Music Technologies group for the nice group climate and for helping with many things in research and beyond. Especially|thank you Alex, Ronny, Christian, Uwe, Estefan´ıa, Patrick, Daniel, Ania, Christian, Anna, Sascha, and Jakob for not only having a prolific working time in Ilmenau but also making friends there. Furthermore, I want to thank several students at TU Ilmenau who worked with me on my topic. Special thanks go to Prof. -

Out of Death and Despair: Elements of Chromaticism in the Songs of Edvard Grieg

Ryan Weber: Out of Death and Despair: Elements of Chromaticism in the Songs of Edvard Grieg Grieg‘s intriguing statement, ―the realm of harmonies has always been my dream world,‖1 suggests the rather imaginative disposition that he held toward the roles of harmonic function within a diatonic pitch space. A great degree of his chromatic language is manifested in subtle interactions between different pitch spaces along the dualistic lines to which he referred in his personal commentary. Indeed, Grieg‘s distinctive style reaches beyond common-practice tonality in ways other than modality. Although his music uses a variety of common nineteenth- century harmonic devices, his synthesis of modal elements within a diatonic or chromatic framework often leans toward an aesthetic of Impressionism. This multifarious language is most clearly evident in the composer‘s abundant songs that span his entire career. Setting texts by a host of different poets, Grieg develops an approach to chromaticism that reflects the Romantic themes of death and despair. There are two techniques that serve to characterize aspects of his multi-faceted harmonic language. The first, what I designate ―chromatic juxtapositioning,‖ entails the insertion of highly chromatic material within ^ a principally diatonic passage. The second technique involves the use of b7 (bVII) as a particular type of harmonic juxtapositioning, for the flatted-seventh scale-degree serves as a congruent agent among the realms of diatonicism, chromaticism, and modality while also serving as a marker of death and despair. Through these techniques, Grieg creates a style that elevates the works of geographically linked poets by capitalizing on the Romantic/nationalistic themes. -

Kostka, Stefan

TEN Classical Serialism INTRODUCTION When Schoenberg composed the first twelve-tone piece in the summer of 192 1, I the "Pre- lude" to what would eventually become his Suite, Op. 25 (1923), he carried to a conclusion the developments in chromaticism that had begun many decades earlier. The assault of chromaticism on the tonal system had led to the nonsystem of free atonality, and now Schoenberg had developed a "method [he insisted it was not a "system"] of composing with twelve tones that are related only with one another." Free atonality achieved some of its effect through the use of aggregates, as we have seen, and many atonal composers seemed to have been convinced that atonality could best be achieved through some sort of regular recycling of the twelve pitch class- es. But it was Schoenberg who came up with the idea of arranging the twelve pitch classes into a particular series, or row, th at would remain essentially constant through- out a composition. Various twelve-tone melodies that predate 1921 are often cited as precursors of Schoenberg's tone row, a famous example being the fugue theme from Richard Strauss's Thus Spake Zararhustra (1895). A less famous example, but one closer than Strauss's theme to Schoenberg'S method, is seen in Example IO-\. Notice that Ives holds off the last pitch class, C, for measures until its dramatic entrance in m. 68. Tn the music of Strauss and rves th e twelve-note theme is a curiosity, but in the mu sic of Schoenberg and his fo ll owers the twelve-note row is a basic shape that can be presented in four well-defined ways, thereby assuring a certain unity in the pitch domain of a composition. -

UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA Los Angeles

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Transcending Imagination; Or, An Approach to Music and Symbolism during the Russian Silver Age A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Musicology by Ryan Isao Rowen 2015 © Copyright by Ryan Isao Rowen 2015 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Transcending Imagination; Or, An Approach to Music and Symbolism during the Russian Silver Age by Ryan Isao Rowen Doctor of Philosophy in Musicology University of California, Los Angeles, 2015 Professor Mitchell Bryan Morris, Chair The Silver Age has long been considered one of the most vibrant artistic movements in Russian history. Due to sweeping changes that were occurring across Russia, culminating in the 1917 Revolution, the apocalyptic sentiments of the general populace caused many intellectuals and artists to turn towards esotericism and occult thought. With this, there was an increased interest in transcendentalism, and art was becoming much more abstract. The tenets of the Russian Symbolist movement epitomized this trend. Poets and philosophers, such as Vladimir Solovyov, Andrei Bely, and Vyacheslav Ivanov, theorized about the spiritual aspects of words and music. It was music, however, that was singled out as possessing transcendental properties. In recent decades, there has been a surge in scholarly work devoted to the transcendent strain in Russian Symbolism. The end of the Cold War has brought renewed interest in trying to understand such an enigmatic period in Russian culture. While much scholarship has been ii devoted to Symbolist poetry, there has been surprisingly very little work devoted to understanding how the soundscape of music works within the sphere of Symbolism. -

MTO 18.4: Chenette, Hearing Counterpoint Within Chromaticism

Volume 18, Number 4, December 2012 Copyright © 2012 Society for Music Theory Hearing Counterpoint Within Chromaticism: Analyzing Harmonic Relationships in Lassus’s Prophetiae Sibyllarum Timothy K. Chenette NOTE: The examples for the (text-only) PDF version of this item are available online at: http://www.mtosmt.org/issues/mto.12.18.4/mto.12.18.4.chenette.php KEYWORDS: Orlandus Lassus (Orlando di Lasso), Prophetiae Sibyllarum, chromaticism, counterpoint, Zarlino, Vicentino, diatonicism, diatonic system, mode, analysis ABSTRACT: Existing analyses of the Prophetiae Sibyllarum generally compare the musical surface to an underlying key, mode, or diatonic system. In contrast, this article asserts that we must value surface relationships in and of themselves, and that certain rules of counterpoint can help us to understand these relationships. Analyses of the Prologue and Sibylla Persica demonstrate some of the insights available to a contrapuntal perspective, including the realization that surprising-sounding music does not always correlate with large numbers of written accidentals. An analysis of Sibylla Europaea suggests some of the ways diatonic and surface-relationship modes of hearing may interact, and highlights the features that may draw a listener’s attention to one of these modes of hearing or the other. Received April 2012 Introduction [1.1] Orlandus Lassus’s cycle Prophetiae Sibyllarum (1550s) is simultaneously familiar and unsettling to the modern listener. (1) The Prologue epitomizes its challenges; see Score and Recording 1. (2) It uses apparent triads, but their roots range so widely that it is difficult to hear them as symbols of an incipient tonality. The piece’s three cadences confirm, in textbook style, Mode 8, (3) but its accidentals complicate a modal designation based on the diatonic octave species. -

Chromatic Sequences

CHAPTER 30 Melodic and Harmonic Symmetry Combine: Chromatic Sequences Distinctions Between Diatonic and Chromatic Sequences Sequences are paradoxical musical processes. At the surface level they provide rapid harmonic rhythm, yet at a deeper level they function to suspend tonal motion and prolong an underlying harmony. Tonal sequences move up and down the diatonic scale using scale degrees as stepping-stones. In this chapter, we will explore the consequences of transferring the sequential motions you learned in Chapter 17 from the asymmetry of the diatonic scale to the symmetrical tonal patterns of the nineteenth century. You will likely notice many similarities of behavior between these new chromatic sequences and the old diatonic ones, but there are differences as well. For instance, the stepping-stones for chromatic sequences are no longer the major and minor scales. Furthermore, the chord qualities of each individual harmony inside a chromatic sequence tend to exhibit more homogeneity. Whereas in the past you may have expected major, minor, and diminished chords to alternate inside a diatonic sequence, in the chromatic realm it is not uncommon for all the chords in a sequence to manifest the same quality. EXAMPLE 30.1 Comparison of Diatonic and Chromatic Forms of the D3 ("Pachelbel") Sequence A. 624 CHAPTER 30 MELODIC AND HARMONIC SYMMETRY COMBINE 625 B. Consider Example 30.1A, which contains the D3 ( -4/ +2)-or "descending 5-6"-sequence. The sequence is strongly goal directed (progressing to ii) and diatonic (its harmonies are diatonic to G major). Chord qualities and distances are not consistent, since they conform to the asymmetry of G major. -

Op. 68 Alexander Scriabin

Analysis of Scriabin’s Sonata No. 9 (“Black Mass”), Op. 68 Alexander Scriabin (1872-1915) was a Russian composer and pianist. An early modern composer, Scriabin’s inventiveness and controversial techniques, inspired by mysticism, synesthesia, and theology, contributed greatly to redefining Russian piano music and the modern musical era as a whole. Scriabin studied at the Moscow Conservatory with peers Anton Arensky, Sergei Taneyev, and Vasily Safonov. His ten piano sonatas are considered some of his greatest masterpieces; the first, Piano Sonata No. 1 In F Minor, was composed during his conservatory years. His Sonata No. 9 (“Black Mass”), Op. 68 was composed in 1912-13 and, more than any other sonata, encapsulates Scriabin’s philosophical and mystical related influences. Sonata No. 9 (“Black Mass”), Op. 68 is a single movement and lasts about 8-10 minutes. Despite the one movement structure, there are eight large tempo markings throughout the piece that imply a sense of slight division. They are: Moderato Quasi Andante (pg. 1), Molto Meno Vivo (pg. 7), Allegro (pg. 10), Allegro Molto (pg. 13), Alla Marcia (pg. 14), Allegro (p. 15), Presto (pg. 16), and Tempo I (pg. 16). As was common in Scriabin’s later works, the piece is extremely chromatic and atonal. Many of its recurring themes center around the extremely dissonant interval of a minor ninth1, and features several transformations of its opening theme, usually increasing in complexity in each of its restatements. Further, a common Scriabin quality involves his use of 1 Wise, H. Harold, “The relationship of pitch sets to formal structure in the last six piano sonatas of Scriabin," UR Research 1987, p. -

Ballet Notes the Seagull March 21 – 25, 2012

Ballet Notes The SeagUll March 21 – 25, 2012 Aleksandar Antonijevic and Sonia Rodriguez as Trigorin and Nina. Photo by Cylla von Tiedemann. Orchestra Violins Trumpets Benjamin Bowman Richard Sandals, Principal Concertmaster Mark Dharmaratnam Lynn KUo, Robert WeymoUth Assistant Concertmaster Trombones DominiqUe Laplante, David Archer, Principal Principal Second Violin Robert FergUson James Aylesworth David Pell, Bass Trombone Jennie Baccante Csaba Ko czó Tuba Sheldon Grabke Sasha Johnson, Principal Xiao Grabke • Nancy Kershaw Harp Sonia Klimasko-LeheniUk LUcie Parent, Principal Celia Franca, C.C., FoUnder Yakov Lerner Timpany George Crum, MUsic Director EmeritUs Jayne Maddison Michael Perry, Principal Ron Mah Karen Kain, C.C. Kevin Garland Aya Miyagawa Percussion Mark MazUr, Acting Artistic Director ExecUtive Director Wendy Rogers Filip Tomov Principal David Briskin Rex Harrington, O.C. Joanna Zabrowarna Kristofer Maddigan MUsic Director and Artist-in-Residence PaUl ZevenhUizen Orchestra Personnel Principal CondUctor Violas Manager and Music Magdalena Popa Lindsay Fischer Angela RUdden, Principal Administrator Principal Artistic Coach Artistic Director, • Theresa RUdolph Koczó, Jean Verch YOU dance / Ballet Master Assistant Principal Assistant Orchestra Valerie KUinka Peter Ottmann Mandy-Jayne Personnel Manager Johann Lotter Raymond Tizzard Senior Ballet Master Richardson Beverley Spotton Senior Ballet Mistress • Larry Toman Librarian LUcie Parent Aleksandar Antonijevic, GUillaUme Côté, Cellos Greta Hodgkinson, Jiˇrí Jelinek, Zdenek Konvalina*, -

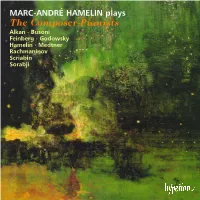

MARC-ANDRÉ HAMELIN Plays the Composer-Pianists Alkan

MARC-ANDRÉ HAMELIN plays The Composer-Pianists Alkan . Busoni Feinberg . Godowsky Hamelin . Medtner Rachmaninov Scriabin Sorabji HE RELATION between musical effect and the technical ‘encore’ repertoire; less convincingly as regards the latter half means necessary for its creation or recreation is apt to of a recital, which at one time might have been entirely Tbe one of opposites. The ‘Representation of Chaos’ with devoted to the type of confection indicated above. However, it which Haydn embarked on The Creation, for example, could can be said that the present offers the best of all liberal worlds, not have succeeded without a conspicuously well ordered in which deeply serious artists may leaven but not demean the compositional technique, nor could the percussion- and intellectual and spiritual weight of their mainstream reper- timpani-based anarchy of Nielsen’s Fourth and Fifth toire by restoring to public attention the full variety and zest of Symphonies or, indeed, the ‘controlled chance’ of more a once discredited milieu. In this connection the abstract recent, aleatory trends. A true chaos of means leads only to nature and importance of ‘pianism’ itself should be empha- incoherence, whereas an intended one of expressive ends may sized: for the serious performing artist the purely physical, be likened to the birth of a universe: explosive, precipitate, callisthenic dimension in Tausig, Rosenthal, Schulz-Evler, seemingly beyond all elemental control, and yet achieved with Scharwenka, Hoffman, Godowsky and others illumines the the pinprick accuracy of some infinitely magnified snowflake, nature of the instrument, and of the art itself, in myriad and defying our later scrutiny to find in it mere accident rather idiosyncratic ways. -

Secondary Dominant Chords.Mus

Secondary Dominants Chromaticism - defined by the use of pitches outside of a diatonic key * nonessential chromaticism describes the use of chromatic non-chord tones * essential chromaticism describes the use of chromatic chord tones creating altered chords Secondary Function Chords - also referred to as applied chords * most common chromatically altered chords * function to tonicize (make sound like tonic) a chord other than tonic * applied to a chord other than tonic and typically function like a dominant or leading-tone chord - secondary function chords can also be used in 2nd inversion as passing and neighbor chords - since only major or minor triads can function as tonic, only major or minor triads may be tonicized - Secondary function chords are labeled with two Roman numerals separated by a slash (/) * the first Roman numeral labels the function of the chord (i.e. V, V7, viiº, or viiº7) * the second Roman numeral labels the chord it is applied to - the tonicized chord * secondary function labels are read as V of __, or viiº of __, etc. Secondary Dominant Chords - most common type of secondardy function chords * always spelled as a major triad or Mm7 chord * used to tonicize a chord whose root is a 5th below (or 4th above) * can create stronger harmonic progressions or emphasize chords other than tonic Spelling Secondary Dominant Chords - there are three steps in spelling a secondary dominant chord * find the root of the chord to be tonicized * determine the pitch a P5 above (or P4 below) * using that pitch as the root, spell a -

Transfer Theory Placement Exam Guide (Pdf)

2016-17 GRADUATE/ transfer THEORY PLACEMENT EXAM guide! Texas woman’s university ! ! 1 2016-17 GRADUATE/transferTHEORY PLACEMENTEXAMguide This! guide is meant to help graduate and transfer students prepare for the Graduate/ Transfer Theory Placement Exam. This evaluation is meant to ensure that students have competence in basic tonal harmony. There are two parts to the exam: written and aural. Part One: Written Part Two: Aural ‣ Four voice part-writing to a ‣ Melodic dictation of a given figured bass diatonic melody ‣ Harmonic analysis using ‣ Harmonic Dictation of a Roman numerals diatonic progression, ‣ Transpose a notated notating the soprano, bass, passage to a new key and Roman numerals ‣ Harmonization of a simple ‣ Sightsinging of a melody diatonic melody that contains some functional chromaticism ! Students must achieve a 75% on both the aural and written components of the exam. If a passing score is not received on one or both sections of the exam, the student may be !required to take remedial coursework. Recommended review materials include most of the commonly used undergraduate music theory texts such as: Tonal Harmony by Koska, Payne, and Almén, The Musician’s Guide to Theory and Analysis by Clendinning and Marvin, and Harmony in Context by Francoli. The exam is given prior to the beginning of both the Fall and Spring Semesters. Please check the TWU MUSIc website (www.twu.edu/music) ! for the exact date and time. ! For further information, contact: Dr. Paul Thomas Assistant Professor of Music Theory and Composition [email protected] 2 2016-17 ! ! ! ! table of Contents ! ! ! ! ! 04 Part-Writing ! ! ! ! ! 08 melody harmonization ! ! ! ! ! 13 transposition ! ! ! ! ! 17 Analysis ! ! ! ! ! 21 melodic dictation ! ! ! ! ! harmonic dictation ! 24 ! ! ! ! Sightsinging examples ! 28 ! ! ! 31 terms ! ! ! ! ! 32 online resources ! 3 PART-Writing Part-writing !Realize the following figured bass in four voices.