Summary of Dissertation Recitals by Zixiang Wang

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Influences of Late Beethoven Piano Sonatas on Schumann's Phantasie in C Major Michiko Inouye [email protected]

Wellesley College Wellesley College Digital Scholarship and Archive Honors Thesis Collection 2014 A Compositional Personalization: Influences of Late Beethoven Piano Sonatas on Schumann's Phantasie in C Major Michiko Inouye [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.wellesley.edu/thesiscollection Recommended Citation Inouye, Michiko, "A Compositional Personalization: Influences of Late Beethoven Piano Sonatas on Schumann's Phantasie in C Major" (2014). Honors Thesis Collection. 224. https://repository.wellesley.edu/thesiscollection/224 This Dissertation/Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Wellesley College Digital Scholarship and Archive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Thesis Collection by an authorized administrator of Wellesley College Digital Scholarship and Archive. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A Compositional Personalization: Influences of Late Beethoven Piano Sonatas on Schumann’s Phantasie in C Major Michiko O. Inouye Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Prerequisite for Honors in the Wellesley College Music Department April 2014 Copyright 2014 Michiko Inouye Acknowledgements This work would not have been possible without the wonderful guidance, feedback, and mentorship of Professor Charles Fisk. I am deeply appreciative of his dedication and patience throughout this entire process. I am also indebted to my piano teacher of four years at Wellesley, Professor Lois Shapiro, who has not only helped me grow as a pianist but through her valuable teaching has also led me to many realizations about Op. 111 and the Phantasie, and consequently inspired me to come up with many of the ideas presented in this thesis. Both Professor Fisk and Professor Shapiro have given me the utmost encouragement in facing the daunting task of both writing about and working to perform such immortal pieces as the Phantasie and Op. -

Beethoven, Bonn and Its Citizens

Beethoven, Bonn and its citizens by Manfred van Rey The beginnings in Bonn If 'musically minded circles' had not formed a citizens' initiative early on to honour the city's most famous son, Bonn would not be proudly and joyfully preparing to celebrate his 250th birthday today. It was in Bonn's Church of St Remigius that Ludwig van Beethoven was baptized on 17 December 1770; it was here that he spent his childhood and youth, received his musical training and published his very first composition at the age of 12. Then the new Archbishop of Cologne, Elector Max Franz from the house of Habsburg, made him a salaried organist in his renowned court chapel in 1784, before dispatching him to Vienna for further studies in 1792. Two years later Bonn, the residential capital of the electoral domain of Cologne, was occupied by French troops. The musical life of its court came to an end, and its court chapel was disbanded. If the Bonn music publisher Nikolaus Simrock (formerly Beethoven’s colleague in the court chapel) had not issued several original editions and a great many reprints of Beethoven's works, and if Beethoven's friend Ferdinand Ries and his father Franz Anton had not performed concerts of his music in Bonn and Cologne, little would have been heard about Beethoven in Bonn even during his lifetime. The first person to familiarise Bonn audiences with Beethoven's music at a high artistic level was Heinrich Karl Breidenstein, the academic music director of Bonn's newly founded Friedrich Wilhelm University. To celebrate the anniversary of his baptism on 17 December 1826, he offered the Bonn première of the Fourth Symphony in his first concert, devoted entirely to Beethoven. -

The University of Chicago Objects of Veneration

THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO OBJECTS OF VENERATION: MUSIC AND MATERIALITY IN THE COMPOSER-CULTS OF GERMANY AND AUSTRIA, 1870-1930 A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE DIVISION OF THE HUMANITIES IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY DEPARTMENT OF MUSIC BY ABIGAIL FINE CHICAGO, ILLINOIS AUGUST 2017 © Copyright Abigail Fine 2017 All rights reserved ii TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF MUSICAL EXAMPLES.................................................................. v LIST OF FIGURES.......................................................................................... vi LIST OF TABLES............................................................................................ ix ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS............................................................................. x ABSTRACT....................................................................................................... xiii INTRODUCTION........................................................................................................ 1 CHAPTER 1: Beethoven’s Death and the Physiognomy of Late Style Introduction..................................................................................................... 41 Part I: Material Reception Beethoven’s (Death) Mask............................................................................. 50 The Cult of the Face........................................................................................ 67 Part II: Musical Reception Musical Physiognomies............................................................................... -

UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA Los Angeles

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Transcending Imagination; Or, An Approach to Music and Symbolism during the Russian Silver Age A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Musicology by Ryan Isao Rowen 2015 © Copyright by Ryan Isao Rowen 2015 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Transcending Imagination; Or, An Approach to Music and Symbolism during the Russian Silver Age by Ryan Isao Rowen Doctor of Philosophy in Musicology University of California, Los Angeles, 2015 Professor Mitchell Bryan Morris, Chair The Silver Age has long been considered one of the most vibrant artistic movements in Russian history. Due to sweeping changes that were occurring across Russia, culminating in the 1917 Revolution, the apocalyptic sentiments of the general populace caused many intellectuals and artists to turn towards esotericism and occult thought. With this, there was an increased interest in transcendentalism, and art was becoming much more abstract. The tenets of the Russian Symbolist movement epitomized this trend. Poets and philosophers, such as Vladimir Solovyov, Andrei Bely, and Vyacheslav Ivanov, theorized about the spiritual aspects of words and music. It was music, however, that was singled out as possessing transcendental properties. In recent decades, there has been a surge in scholarly work devoted to the transcendent strain in Russian Symbolism. The end of the Cold War has brought renewed interest in trying to understand such an enigmatic period in Russian culture. While much scholarship has been ii devoted to Symbolist poetry, there has been surprisingly very little work devoted to understanding how the soundscape of music works within the sphere of Symbolism. -

A Discussion of the Piano Sonata No. 2 in D Minor, Op

A DISCUSSION OF THE PIANO SONATA NO. 2 IN D MINOR, OP. 14, BY SERGEI PROKOFIEV A PAPER ACCOMPANYING A THREE CREDIT-HOUR CREATIVE PROJECT RECITAL SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE MASTER OF MUSIC BY QINYUAN LIN DR. ROBERT PALMER‐ ADVISOR BALL STATE UNIVERSITY MUNCIE, INDIANA JULY 2010 Preface The goal of this paper is to introduce the piece, provide historical background, and focus on the musical analysis of the sonata. The introduction of the piece will include a brief biography of Sergei Prokofiev and the circumstance in which the piece was composed. A general overview of the composition, performance, and perception of this piece will be discussed. The bulk of the paper will focus on the musical analysis of Piano Sonata No. 2 from my perspective as a performer of the piece. It will be broken into four sections, one each for the four movements in the sonata. In the discussion for each movement, I will analyze the forms used as well as required techniques and difficulties to be considered by the pianist. The conclusion will summarize the discussion. i Table of Contents Preface ________________________________________________________________ i Introduction ____________________________________________________________ 1 The First Movement: Allegro, ma non troppo __________________________________ 5 The Second Movement: Scherzo ____________________________________________ 9 The Third Movement: Andante ____________________________________________ 11 The Fourth Movement: Vivace ____________________________________________ 13 Conclusion ____________________________________________________________ 17 Bibliography __________________________________________________________ 18 ii Introduction Sergei Prokofiev was born in 1891 to parents Sergey and Mariya and grew up in comfortable circumstances. His mother, Mariya, had a feeling for the arts and gave the young Prokofiev his first piano lessons at the age of four. -

Function and Structure of Transitions in Sonata — Form Music of Mozart Robert Batt

Document généré le 1 oct. 2021 08:37 Canadian University Music Review Revue de musique des universités canadiennes --> Voir l’erratum concernant cet article Function and Structure of Transitions in Sonata — Form Music of Mozart Robert Batt Volume 9, numéro 1, 1988 URI : https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/1014927ar DOI : https://doi.org/10.7202/1014927ar Aller au sommaire du numéro Éditeur(s) Canadian University Music Society / Société de musique des universités canadiennes ISSN 0710-0353 (imprimé) 2291-2436 (numérique) Découvrir la revue Citer cet article Batt, R. (1988). Function and Structure of Transitions in Sonata — Form Music of Mozart. Canadian University Music Review / Revue de musique des universités canadiennes, 9(1), 157–201. https://doi.org/10.7202/1014927ar All Rights Reserved © Canadian University Music Society / Société de musique Ce document est protégé par la loi sur le droit d’auteur. L’utilisation des des universités canadiennes, 1988 services d’Érudit (y compris la reproduction) est assujettie à sa politique d’utilisation que vous pouvez consulter en ligne. https://apropos.erudit.org/fr/usagers/politique-dutilisation/ Cet article est diffusé et préservé par Érudit. Érudit est un consortium interuniversitaire sans but lucratif composé de l’Université de Montréal, l’Université Laval et l’Université du Québec à Montréal. Il a pour mission la promotion et la valorisation de la recherche. https://www.erudit.org/fr/ FUNCTION AND STRUCTURE OF TRANSITIONS IN SONATA-FORM MUSIC OF MOZART Robert Batt The transition, sometimes referred to as the bridge, is usually regarded as the section of sonata form responsible for modulating from the pri• mary to the secondary key as well as for effecting a structural contrast between the two thematic sections. -

Op. 68 Alexander Scriabin

Analysis of Scriabin’s Sonata No. 9 (“Black Mass”), Op. 68 Alexander Scriabin (1872-1915) was a Russian composer and pianist. An early modern composer, Scriabin’s inventiveness and controversial techniques, inspired by mysticism, synesthesia, and theology, contributed greatly to redefining Russian piano music and the modern musical era as a whole. Scriabin studied at the Moscow Conservatory with peers Anton Arensky, Sergei Taneyev, and Vasily Safonov. His ten piano sonatas are considered some of his greatest masterpieces; the first, Piano Sonata No. 1 In F Minor, was composed during his conservatory years. His Sonata No. 9 (“Black Mass”), Op. 68 was composed in 1912-13 and, more than any other sonata, encapsulates Scriabin’s philosophical and mystical related influences. Sonata No. 9 (“Black Mass”), Op. 68 is a single movement and lasts about 8-10 minutes. Despite the one movement structure, there are eight large tempo markings throughout the piece that imply a sense of slight division. They are: Moderato Quasi Andante (pg. 1), Molto Meno Vivo (pg. 7), Allegro (pg. 10), Allegro Molto (pg. 13), Alla Marcia (pg. 14), Allegro (p. 15), Presto (pg. 16), and Tempo I (pg. 16). As was common in Scriabin’s later works, the piece is extremely chromatic and atonal. Many of its recurring themes center around the extremely dissonant interval of a minor ninth1, and features several transformations of its opening theme, usually increasing in complexity in each of its restatements. Further, a common Scriabin quality involves his use of 1 Wise, H. Harold, “The relationship of pitch sets to formal structure in the last six piano sonatas of Scriabin," UR Research 1987, p. -

Mystic Chord Harmonic and Light Transformations In

MYSTIC CHORD HARMONIC AND LIGHT TRANSFORMATIONS IN ALEXANDER SCRIABIN’S PROMETHEUS by TYLER MATTHEW SECOR A THESIS Presented to the School of Music and Dance and the Graduate School of the University of Oregon in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts September 2013 THESIS APPROVAL PAGE Student: Tyler Matthew Secor Title: Mystic Chord Harmonic and Light Transformations in Alexander Scriabin’s Prometheus This thesis has been accepted and approved in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Master of Arts degree in the School of Music and Dance by: Dr. Jack Boss Chair Dr. Stephen Rodgers Member Dr. Frank Diaz Member and Kimberly Andrews Espy Vice President for Research and Innovation Dean of the Graduate School Original approval signatures are on file with the University of Oregon Graduate School. Degree awarded September 2013 ii © 2013 Tyler Matthew Secor iii THESIS ABSTRACT Tyler Matthew Secor Master of Arts School of Music and Dance September 2013 Title: Mystic Chord Harmonic and Light Transformations in Alexander Scriabin’s Prometheus This thesis seeks to explore the voice leading parsimony, bass motion, and chromatic extensions present in Alexander Scriabin’s Prometheus. Voice leading will be explored using Neo-Riemannian type transformations followed by network diagrams to track the mystic chord movement throughout the symphony. Bass motion and chromatic extensions are explored by expanding the current notion of how the luce voices function in outlining and dictating the harmonic motion. Syneathesia -

Ballet Notes the Seagull March 21 – 25, 2012

Ballet Notes The SeagUll March 21 – 25, 2012 Aleksandar Antonijevic and Sonia Rodriguez as Trigorin and Nina. Photo by Cylla von Tiedemann. Orchestra Violins Trumpets Benjamin Bowman Richard Sandals, Principal Concertmaster Mark Dharmaratnam Lynn KUo, Robert WeymoUth Assistant Concertmaster Trombones DominiqUe Laplante, David Archer, Principal Principal Second Violin Robert FergUson James Aylesworth David Pell, Bass Trombone Jennie Baccante Csaba Ko czó Tuba Sheldon Grabke Sasha Johnson, Principal Xiao Grabke • Nancy Kershaw Harp Sonia Klimasko-LeheniUk LUcie Parent, Principal Celia Franca, C.C., FoUnder Yakov Lerner Timpany George Crum, MUsic Director EmeritUs Jayne Maddison Michael Perry, Principal Ron Mah Karen Kain, C.C. Kevin Garland Aya Miyagawa Percussion Mark MazUr, Acting Artistic Director ExecUtive Director Wendy Rogers Filip Tomov Principal David Briskin Rex Harrington, O.C. Joanna Zabrowarna Kristofer Maddigan MUsic Director and Artist-in-Residence PaUl ZevenhUizen Orchestra Personnel Principal CondUctor Violas Manager and Music Magdalena Popa Lindsay Fischer Angela RUdden, Principal Administrator Principal Artistic Coach Artistic Director, • Theresa RUdolph Koczó, Jean Verch YOU dance / Ballet Master Assistant Principal Assistant Orchestra Valerie KUinka Peter Ottmann Mandy-Jayne Personnel Manager Johann Lotter Raymond Tizzard Senior Ballet Master Richardson Beverley Spotton Senior Ballet Mistress • Larry Toman Librarian LUcie Parent Aleksandar Antonijevic, GUillaUme Côté, Cellos Greta Hodgkinson, Jiˇrí Jelinek, Zdenek Konvalina*, -

Florida State University Libraries

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2009 Gustav Mahler, Alfred Roller, and the Wagnerian Gesamtkunstwerk: Tristan and Affinities Between the Arts at the Vienna Court Opera Stephen Carlton Thursby Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF MUSIC GUSTAV MAHLER, ALFRED ROLLER, AND THE WAGNERIAN GESAMTKUNSTWERK: TRISTAN AND AFFINITIES BETWEEN THE ARTS AT THE VIENNA COURT OPERA By STEPHEN CARLTON THURSBY A Dissertation submitted to the College of Music in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Degree Awarded: Spring Semester, 2009 The members of the Committee approve the Dissertation of Stephen Carlton Thursby defended on April 3, 2009. _______________________________ Denise Von Glahn Professor Directing Dissertation _______________________________ Lauren Weingarden Outside Committee Member _______________________________ Douglass Seaton Committee Member Approved: ___________________________________ Douglass Seaton, Chair, Musicology ___________________________________ Don Gibson, Dean, College of Music The Graduate School has verified and approved the above named committee members. ii To my wonderful wife Joanna, for whose patience and love I am eternally grateful. In memory of my grandfather, James C. Thursby (1926-2008). iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The completion of this dissertation would not have been possible without the generous assistance and support of numerous people. My thanks go to the staff of the Austrian Theater Museum and Austrian National Library-Music Division, especially to Dr. Vana Greisenegger, curator of the visual materials in the Alfred Roller Archive of the Austrian Theater Museum. I would also like to thank the musicology faculty of the Florida State University College of Music for awarding me the Curtis Mayes Scholar Award, which funded my dissertation research in Vienna over two consecutive summers (2007- 2008). -

Ludwig Van Beethoven Hdt What? Index

LUDWIG VAN BEETHOVEN HDT WHAT? INDEX LUDWIG VAN BEETHOVEN LUDWIG VAN BEETHOVEN 1756 December 8, Wednesday: The Emperor’s son Maximilian Franz, the Archduke who in 1784 would become the patron of the young Ludwig van Beethoven, was born on the Emperor’s own birthday. Christoph Willibald Gluck’s dramma per musica Il rè pastore to words of Metastasio was being performed for the initial time, in the Burgtheater, Vienna, in celebration of the Emperor’s birthday. ONE COULD BE ELSEWHERE, AS ELSEWHERE DOES EXIST. ONE CANNOT BE ELSEWHEN SINCE ELSEWHEN DOES NOT. Ludwig van Beethoven “Stack of the Artist of Kouroo” Project HDT WHAT? INDEX LUDWIG VAN BEETHOVEN LUDWIG VAN BEETHOVEN 1770 December 16, Sunday: This is the day on which we presume that Ludwig van Beethoven was born.1 December 17, Monday: Ludwig van Beethoven was baptized at the Parish of St. Remigius in Bonn, Germany, the 2d and eldest surviving of 7 children born to Johann van Beethoven, tenor and music teacher, and Maria Magdalena Keverich (widow of M. Leym), daughter of the chief kitchen overseer for the Elector of Trier. Given the practices of the day, it is presumed that the infant had been born on the previous day. NEVER READ AHEAD! TO APPRECIATE DECEMBER 17TH, 1770 AT ALL ONE MUST APPRECIATE IT AS A TODAY (THE FOLLOWING DAY, TOMORROW, IS BUT A PORTION OF THE UNREALIZED FUTURE AND IFFY AT BEST). 1. Q: How come Austrians have the rep of being so smart? A: They’ve managed somehow to create the impression that Beethoven, born in Germany, was Austrian, while Hitler, born in Austria, was German! HDT WHAT? INDEX LUDWIG VAN BEETHOVEN LUDWIG VAN BEETHOVEN 1778 March 26, Thursday: In the Academy Room on the Sternengasse of Cologne, Ludwig van Beethoven appeared in concert for the initial time, with his father and another child-student of his father. -

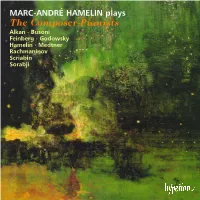

MARC-ANDRÉ HAMELIN Plays the Composer-Pianists Alkan

MARC-ANDRÉ HAMELIN plays The Composer-Pianists Alkan . Busoni Feinberg . Godowsky Hamelin . Medtner Rachmaninov Scriabin Sorabji HE RELATION between musical effect and the technical ‘encore’ repertoire; less convincingly as regards the latter half means necessary for its creation or recreation is apt to of a recital, which at one time might have been entirely Tbe one of opposites. The ‘Representation of Chaos’ with devoted to the type of confection indicated above. However, it which Haydn embarked on The Creation, for example, could can be said that the present offers the best of all liberal worlds, not have succeeded without a conspicuously well ordered in which deeply serious artists may leaven but not demean the compositional technique, nor could the percussion- and intellectual and spiritual weight of their mainstream reper- timpani-based anarchy of Nielsen’s Fourth and Fifth toire by restoring to public attention the full variety and zest of Symphonies or, indeed, the ‘controlled chance’ of more a once discredited milieu. In this connection the abstract recent, aleatory trends. A true chaos of means leads only to nature and importance of ‘pianism’ itself should be empha- incoherence, whereas an intended one of expressive ends may sized: for the serious performing artist the purely physical, be likened to the birth of a universe: explosive, precipitate, callisthenic dimension in Tausig, Rosenthal, Schulz-Evler, seemingly beyond all elemental control, and yet achieved with Scharwenka, Hoffman, Godowsky and others illumines the the pinprick accuracy of some infinitely magnified snowflake, nature of the instrument, and of the art itself, in myriad and defying our later scrutiny to find in it mere accident rather idiosyncratic ways.