The Critical Reception of Alexei Stanchinsky* Akvilė Stuart1 Болесни Геније?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Fourteenth Season: Russian Reflections July 15–August 6, 2016 David Finckel and Wu Han, Artistic Directors Experience the Soothing Melody STAY with US

The Fourteenth Season: Russian Reflections July 15–August 6, 2016 David Finckel and Wu Han, Artistic Directors Experience the soothing melody STAY WITH US Spacious modern comfortable rooms, complimentary Wi-Fi, 24-hour room service, fitness room and a large pool. Just two miles from Stanford. BOOK EVENT MEETING SPACE FOR 10 TO 700 GUESTS. CALL TO BOOK YOUR STAY TODAY: 650-857-0787 CABANAPALOALTO.COM DINE IN STYLE Chef Francis Ramirez’ cuisine centers around sourcing quality seasonal ingredients to create delectable dishes combining French techniques with a California flare! TRY OUR CHAMPAGNE SUNDAY BRUNCH RESERVATIONS: 650-628-0145 4290 EL CAMINO REAL PALO ALTO CALIFORNIA 94306 Music@Menlo Russian Reflections the fourteenth season July 15–August 6, 2016 D AVID FINCKEL AND WU HAN, ARTISTIC DIRECTORS Contents 2 Season Dedication 3 A Message from the Artistic Directors 4 Welcome from the Executive Director 4 Board, Administration, and Mission Statement 5 R ussian Reflections Program Overview 6 E ssay: “Natasha’s Dance: The Myth of Exotic Russia” by Orlando Figes 10 Encounters I–III 13 Concert Programs I–VII 43 Carte Blanche Concerts I–IV 58 Chamber Music Institute 60 Prelude Performances 67 Koret Young Performers Concerts 70 Master Classes 71 Café Conversations 72 2016 Visual Artist: Andrei Petrov 73 Music@Menlo LIVE 74 2016–2017 Winter Series 76 Artist and Faculty Biographies A dance lesson in the main hall of the Smolny Institute, St. Petersburg. Russian photographer, twentieth century. Private collection/Calmann and King Ltd./Bridgeman Images 88 Internship Program 90 Glossary 94 Join Music@Menlo 96 Acknowledgments 101 Ticket and Performance Information 103 Map and Directions 104 Calendar www.musicatmenlo.org 1 2016 Season Dedication Music@Menlo’s fourteenth season is dedicated to the following individuals and organizations that share the festival’s vision and whose tremendous support continues to make the realization of Music@Menlo’s mission possible. -

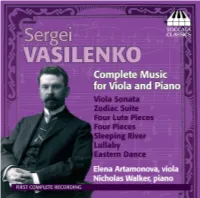

Toccata Classics TOCC 0127 Notes

SERGEI VASILENKO AND THE VIOLA by Elena Artamonova The viola is occasionally referred to as ‘the Cinderella of instruments’ – and, indeed, it used to take a fairy godmother of a player to allow this particular Cinderella to go to the ball; the example usually cited in the liberation of the viola in a solo role is the British violist Lionel Tertis. Another musician to pay the instrument a similar honour – as a composer rather than a player – was the Russian Sergei Vasilenko (1872–1956), all of whose known compositions for viola, published and unpublished, are to be heard on this CD, the fruit of my investigations in libraries and archives in Moscow and London. None is well known; some are not even included in any of the published catalogues of Vasilenko’s music. Only the Sonata was recorded previously, first in the 1960s by Georgy Bezrukov, viola, and Anatoly Spivak, piano,1 and again in 2007 by Igor Fedotov, viola, and Leonid Vechkhayzer, piano;2 the other compositions receive their first recordings here. Sergei Nikiforovich Vasilenko had a long and distinguished career as composer, conductor and pedagogue in the first half of the twentieth century. He was born in Moscow on 30 March 1872 into an aristocratic family, whose inner circle of friends consisted of the leading writers and artists of the time, but his interest in music was rather capricious in his early childhood: he started to play piano from the age of six only to give it up a year later, although he eventually resumed his lessons. In his mid-teens, after two years of tuition on the clarinet, he likewise gave it up in favour of the oboe. -

The Development of the Russian Piano Concerto in the Nineteenth Century Jeremy Paul Norris Doctor of Philosophy Department of Mu

The Development of the Russian Piano Concerto in the Nineteenth Century Jeremy Paul Norris Doctor of Philosophy Department of Music 1988 December The Development of the Russian Piano Concerto in the Nineteenth Century Jeremy Paul Norris The Russian piano concerto could not have had more inauspicious beginnings. Unlike the symphonic poem (and, indirectly, the symphony) - genres for which Glinka, the so-called 'Father of Russian Music', provided an invaluable model: 'Well? It's all in "Kamarinskaya", just as the whole oak is in the acorn' to quote Tchaikovsky - the Russian piano concerto had no such indigenous prototype. All that existed to inspire would-be concerto composers were a handful of inferior pot- pourris and variations for piano and orchestra and a negligible concerto by Villoing dating from the 1830s. Rubinstein's five con- certos certainly offered something more substantial, as Tchaikovsky acknowledged in his First Concerto, but by this time the century was approaching its final quarter. This absence of a prototype is reflected in all aspects of Russian concerto composition. Most Russian concertos lean perceptibly on the stylistic features of Western European composers and several can be justly accused of plagiarism. Furthermore, Russian composers faced formidable problems concerning the structural organization of their concertos, a factor which contributed to the inability of several, including Balakirev and Taneyev, to complete their works. Even Tchaikovsky encountered difficulties which he was not always able to overcome. The most successful Russian piano concertos of the nineteenth century, Tchaikovsky's No.1 in B flat minor, Rimsky-Korsakov's Concerto in C sharp minor and Balakirev's Concerto in E flat, returned ii to indigenous sources of inspiration: Russian folk song and Russian orthodox chant. -

Piano Sonatas

PIANO SONATAS Ludwig van Beethoven (1770-1827) Piano Sonata No. 27 in E minor, Op. 90 13:08 1 I. Mit Lebhaftigkeit und durchaus mit Empfindung und Ausdruck 6:03 2 II. Nicht zu geschwind und sehr singbar vorzutragen 7:05 Alexander Scriabin (1872-1915) 3 Piano Sonata No. 10, Op. 70 12:57 Sergei Prokofiev (1891-1953) Piano Sonata No. 2 in D minor, Op. 14 20:55 4 I. Allegro non troppo — più mosso — tempo primo 6:34 5 II. Scherzo: Allegro marcato 2:32 6 III. Andante 6:11 7 IV. Vivace — moderato — vivace 5:37 bonus tracks: Claude Debussy (1862-1918) Estampes 16:00 8 I. Pagodes 6:27 9 II. La soirée dans Grenade 5:18 10 III. Jardins sous la pluie 4:14 total playing time: 63:01 NATALIA ANDREEVA piano The Music I recorded these piano sonatas and “Estampes” at different stages of my life. It was a long journey: practicing, performing, teaching and doing the research… all helped me to create my own mental pictures and images of these piano masterpieces. Beethoven: Piano Sonata No. 27 in E minor, Op. 90 “Why do I write? What I have in my heart must come out; and that is why I compose.” Those are famous words of the composer.1 There is a 4-5 year gap between Beethoven’s Piano Sonata Op. 81a (completed in 1809) and Op. 90, composed in 1814. The Canadian pianist Anton Kuetri (who has recorded Beethoven’s complete Piano Sonatas) wrote: “For four years Beethoven wrote no sonatas, symphonies or string quartets. -

Downloaded From: Usage Rights: Creative Commons: Attribution-Noncommercial-No Deriva- Tive Works 4.0

Paliy, Olga (2017) Taneyev’s Influence on Practice and Performance Strate- gies in Early 20th Century Russian Polyphonic Music. Doctoral thesis (PhD), awarded for a Collaborative Programme of Research at the Royal Northern College of Music by the Manchester Metropolitan University. Downloaded from: https://e-space.mmu.ac.uk/626473/ Usage rights: Creative Commons: Attribution-Noncommercial-No Deriva- tive Works 4.0 Please cite the published version https://e-space.mmu.ac.uk TANEYEV’S INFLUENCE ON PRACTICE AND PERFORMANCE STRATEGIES IN EARLY 20th CENTURY RUSSIAN POLYPHONIC MUSIC OLGA PALIY This thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the Manchester Metropolitan University for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Awarded for a Collaborative Programme of Research at the Royal Northern College of Music by the Manchester Metropolitan University ROYAL NORTHERN COLLEGE OF MUSIC AND THE MANCHESTER METROPOLITAN UNIVERSITY January 2017 TABLE OF CONTENTS Abstract …………………………………………………………………………………………………………….. 5 Acknowledgments …….………………………………………………………….............................. 7 INTRODUCTION …………………………………………………………………………………………………. 8 CHAPTER ONE Taneyev’s contribution to Russian musical culture 1. Taneyev in the Moscow Conservatory: ……………………………….… 14 1.1. Founder of counterpoint class …………………………….…………. 15 2. Taneyev’s study of counterpoint: 2.1. Convertible Counterpoint in the Strict Style …………………….. 16 2.2. The Study of Canon ………………………………………………………… 18 3. Taneyev – pianist …………………………………………………………………. 19 CHAPTER TWO Interrelation of the fugue with other genres 1. Fugue as a model of generic counterpoint from Glinka to Taneyev …... 23 2. Fugue in Taneyev’s piano works: ……………………………………………………... 29 2.1. Fugue in D minor (unpublished) ……………….………………………..… 29 2.2. Prelude and Fugue in G sharp minor Op.29 ….……..………….……. 32 3. Implementation of the fugue in piano and chamber works of Taneyev, his students and successors: ………………………………………….………..…….… 41 3.1. -

The Impact of Russian Music in England 1893-1929

THE IMPACT OF RUSSIAN MUSIC IN ENGLAND 1893-1929 by GARETH JAMES THOMAS A thesis submitted to The University of Birmingham for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Department of Music School of Humanities The University of Birmingham March 2005 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. ABSTRACT This thesis is an investigation into the reception of Russian music in England for the period 1893-1929 and the influence it had on English composers. Part I deals with the critical reception of Russian music in England in the cultural and political context of the period from the year of Tchaikovsky’s last successful visit to London in 1893 to the last season of Diaghilev’s Ballet russes in 1929. The broad theme examines how Russian music presented a challenge to the accepted aesthetic norms of the day and how this, combined with the contextual perceptions of Russia and Russian people, problematized the reception of Russian music, the result of which still informs some of our attitudes towards Russian composers today. Part II examines the influence that Russian music had on British composers of the period, specifically Stanford, Bantock, Vaughan Williams, Holst, Frank Bridge, Bax, Bliss and Walton. -

Download (2MB)

CATALOGUE OF THE I A BUNIN, V N BUNINA, L F ZUROV AND E M LOPATINA COLLECTIONS LEEDSRUSSIANARCHIVE UNIVERSITY OF LEEDS _________________________________ ANTHONY J HEYWOOD * CATALOGUE OF THE I A BUNIN, V N BUNINA, L F ZUROV AND E M LOPATINA COLLECTIONS * EDITED BY RICHARD D DAVIES, WITH THE ASSISTANCE OF DANIEL RINIKER (REVISED EDITION)* LEEDS LEEDS UNIVERSITY PRESS 2011* The preparation and publication of this catalogue was funded by the generosity of The Leverhulme Trust. The cover illustration is the Bunin family coat-of-arms (MS.1066/1229) ISBN 0 85316 215 8 © Anthony J Heywood, 2000 & 2011* © The Ivan & Vera Bunin and Leonid Zurov Estates/University of Leeds, 2000 & 2011* * Indicates revisions to the 2000 catalogue All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form, or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise) without the prior written permission of the publisher. Any person who does any unauthorised act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages. Leeds Russian Archive, Brotherton Library, University of Leeds, Leeds, W Yorks, LS2 9JT, Great Britain. Printed by the Leeds University Printing Service To the memory of Militsa Eduardovna Greene (1908-1998) Светлой памяти Милицы Эдуардовны Грин CONTENTS INTRODUCTION I A BUNIN COLLECTION V N BUNINA COLLECTION L F ZUROV COLLECTION E M LOPATINA COLLECTION INDEX Contents CONTENTS INTRODUCTION Ivan Alekseevich Bunin (1870-1953) ................................................................................... xix Vera Nikolaevna Bunina (1881-1961) ................................................................................ xxiii Leonid Fedorovich Zurov (1902-1971) ................................................................................ xxv Ekaterina Mikhailovna Lopatina (1865-1935) .................................................................. -

![Known Also As Louis Victor Franz Saar [Lôô-Ee Veek-TAWR FRAHNZ SAHAHR]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3525/known-also-as-louis-victor-franz-saar-l%C3%B4%C3%B4-ee-veek-tawr-frahnz-sahahr-4563525.webp)

Known Also As Louis Victor Franz Saar [Lôô-Ee Veek-TAWR FRAHNZ SAHAHR]

Saar C Louis Victor Saar C LOO-uss VICK-tur SAR C (known also as Louis Victor Franz Saar [lôô-ee veek-TAWR FRAHNZ SAHAHR]) Saar C Mart Saar C MART SAHAHR Saari C Tuula Saari C TÔÔÔÔ-lah SAHAH-rih Saariaho C Kaija Saariaho C KAHIH-yah SAHAH-rihah-haw C (known also as Kaija Anneli [AHN-neh-lih] Saariaho) Saavedra C Ángel Pérez de Saavedra C AHN-hell PAY-rehth day sah-VAY-drah Sabaneyev C Leonid Sabaneyev C lay-ah-NYITT sah-bah-NAY-eff C (known also as Leonid Leonidovich [lay-ah-NYEE-duh-vihch] Sabaneyev) Sabata C Victor de Sabata C VEEK-tohr day sah-BAH-tah C (known also as Vittorio de Sabata [veet-TOH-reeo day sah-BAH-tah]) Sabater C Juan María Thomas Sabater C hooAHN mah-REE-ah TOH-mahss sah-vah-TEHR C (known also as Juan María Thomas) Sabbatini C Galeazzo Sabbatini C gah-lay-AHT-tso sahb-bah-TEE-nee Sabbatini C Giuseppe Sabbatini C joo-ZAYP-pay sah-bah-TEE-nee Sabbatini C Luigi Antonio Sabbatini C looEE-jee ahn-TAW-neeo sahb-bah-TEE-nee Sabbato sancto C SAHB-bah-toh SAHNK-toh C (the Crucifixion before Easter Sunday) C (general title for individually numbered Responsoria by Carlo Gesualdo [KAR-lo jay-zooAHL- doh]) Sabin C Robert Sabin C RAH-burt SAY-binn Sabin C Wallace Arthur Sabin C WAHL-luss AR-thur SAY-binn Sabina C Karel Sabina C KAH-rell SAH-bih-nah Sabina C sah-BEE-nah C (character in the opera La fiamma [lah feeAHM-mah] — The Flame; music by Ottorino Respighi [oht-toh-REE-no ray-SPEE-ghee] and libretto by Claudio Guastalla [KLAHOO-deeo gooah-STAHL-lah]) Sabio C Alfonso el Sabio C ahl-FAWN-so ell SAH-veeo Sacchetti C Liberius Sacchetti C lyee-BAY-rihôôss sahk-KAY-tih Sacchi C Don Giovenale Sacchi C DOHN jo-vay-NAH-lay SAHK-kee Sacchini C Antonio Sacchini C ahn-TAW-neeo sahk-KEE-nee C (known also as Antonio Maria Gasparo Gioacchino [mah-REE-ah gah-SPAH-ro johahk-KEE-no] Sacchini) Sacco C P. -

Forgotten Russian Piano Music: the Sonatas of Anatoly Aleksandrov Irina Pevzner University of South Carolina

University of South Carolina Scholar Commons Theses and Dissertations 1-1-2013 Forgotten Russian Piano Music: the Sonatas of Anatoly Aleksandrov Irina Pevzner University of South Carolina Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/etd Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Pevzner, I.(2013). Forgotten Russian Piano Music: the Sonatas of Anatoly Aleksandrov. (Master's thesis). Retrieved from https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/etd/2559 This Open Access Thesis is brought to you by Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FORGOTTEN RUSSIAN PIANO MUSIC: THE SONATAS OF ANATOLY ALEKSANDROV by Irina Pevzner Bachelor of Music Mansfield University of Pennsylvania, 2000 Master of Music Carnegie Mellon University, 2003 Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in Music Performance School of Music University of South Carolina 2013 Accepted by: Marina Lomazov, Major Professor Chairman, Examining Committee Charles Fugo, Committee Member Joseph Rackers, Committee Member Ellen Exner, Committee Member Lacy Ford, Vice Provost and Dean of Graduate Studies Copyright by Irina Pevzner, 2013 All Rights Reserved ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to acknowledge several individuals, who played an important role in preparation of the current document. Above all, I would like to distinguish Dr. Marina Lomazov, my piano professor and the director of the dissertation committee, for inspiring me to achieve a higher level of musicianship and guiding me with unreserved care and perseverance to become a more confident and competent performer. -

Alexander Tcherepnin's Symphony No.1

ALEXANDER TCHEREPNIN’S SYMPHONY NO.1: VALIDATING THE WORK WITHIN THE CANON OF SYMPHONIC COMPOSITION by JOSHUA LEE BEDFORD (Under the Direction of David Haas) ABSTRACT Alexander Tcherepnin’s First Symphony was his first major work for orchestra. In this thesis I will reassess the work by discussing three compositional challenges that he faced by writing a symphony in the 1920s. First, Tcherepnin’s incorporation of new compositional trends of the 1920s will be examined to contextualize his symphony. Secondly, the general challenges confronting modern symphonists will be summarized, based on the views of prominent critics and scholars. Finally, Tcherepnin’s unique compositional method will be assessed, based on its capability to produce the qualities traditionally associated with the symphonic genre. The examination of each of these challenges will provide a means for assessing Tcherepnin’s achievement and understanding its relationship to symphonic traditions. INDEX WORDS: Alexander Tcherepnin, symphony, compositional methods, interpoint, nine-note scale, symphonic criteria, 1920s ALEXANDER TCHEREPNIN’S FIRST SYMPHONY: VALIDATING THE WORK WITHIN THE CANON OF MODERN SYMPHONIC COMPOSITION by JOSHUA LEE BEDFORD B.M.E, Indiana State University, 2011 A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of The University of Georgia in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree MASTER OF ARTS ATHENS, GEORGIA 2013 © 2013 Joshua Lee Bedford All Rights Reserved ALEXANDER TCHEREPNIN’S FIRST SYMPHONY: VALIDATING THE WORK WITHIN THE CANON OF MODERN SYMPHONIC COMPOSITION by JOSHUA LEE BEDFORD Major Professor: David Haas Committee: Stephen Valdez Rebecca Simpson-Litke Electronic Version Approved: Maureen Grasso Dean of the Graduate School The University of Georgia May 2013 iv DEDICATION For my mother and grandmother, Marceé Bedford and Rhonda Oldham v ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS First, I would like to thank Benjamin Folkman for his invaluable insight, his continuous support, and his generous contribution to this project. -

An Examination of Vissarion Shebalin's Concertino for Horn Op

An Examination of Vissarion Shebalin’s Concertino for Horn Op. 14, No. 2 By Sally Elaine Podrebarac, BA, MM A Document In Horn Performance Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Texas Tech University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS Performance (Horn) Approved Christopher M. Smith Co-Chairperson of the Committee Lisa Rogers Co-Chairperson of the Committee James T. Decker Accepted Mark Sheridan Dean of the Graduate School May 2018 Copyright 2018, Sally Elaine Podrebarac Texas Tech University, Sally Elaine Podrebarac, May 2018 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to show my gratitude to Professor Christopher M. Smith for his support throughout my doctoral degree. I would like to thank all those whose assistance proved to be a milestone in the accomplishment of this document, including Dr. Lisa Rogers and Professor James Decker. Special thanks to Dr. Nataliya Sukhina for her diligent help with pronunciations and knowledge pertaining to Russia. Special thanks to Professor Rachel Mazzucco for her supervision of the performance practice analysis of this document. Finally, I would like to thank Jason Davis, my fiancé, for his unwavering support. i Texas Tech University, Sally Elaine Podrebarac, May 2018 TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgments. i Abstract. iv List of Figures. v List of Examples. v Chapter I. Overview. 1 Justification for the Study. 2 Limitations of the Study. 2 Review of Related Literature. 3 II. Brief Biographical Sketch. 5 Personal Life. 5 Nikolay Myaskovsky. 6 Dmitri Shostakovich. 9 Teaching. 10 RAPM and ACM. 12 (Russian Association of Proletarian Musicians and Association for Contemporary Music) Formalism and Social Realism. -

Program Notes: the Russian Quartet Notes on the Program by Dr

Program Notes: The Russian Quartet Notes on the program by Dr. Richard E. Rodda Sergei RachmaninoV When the Germans invaded Soviet Russia in June 1941, Prokofiev and sev- (Born March 20/April 1, 1873, Oneg, Russia; died March 28, 1943, Beverly eral other composers were evacuated from Moscow to Nalchik, the capital Hills, California) of the Kabardino-Balkaria Republic, in the northern Caucasus Mountains. Two Movements for String Quartet Prokofiev recalled in his autobiography, “The Chairman of the Arts Com- mittee in Nalchik said to us, ‘Look here...you have a gold mine of folk music Composed: 1889 in this region that has practically been untapped.’ He went to his files and Other works from this period: Two Pieces for Piano, Six Hands (1890– brought out some songs collected by earlier musical visitors to Nalchik. The 1891); Aleko (The Gypsies) (opera) (1892); Capriccio on Gypsy Themes, material proved to be very fresh and original, and I settled on writing a op. 12 (1892, 1894) string quartet, thinking that the combination of new, untouched Oriental Approximate duration: 13 minutes folklore with the most classical of classic forms, the string quartet, ought to produce interesting and unexpected results.” Prokofiev began the Quartet Rachmaninov was born of noble blood, but his father, Vasily, squandered no. 2 on November 2, finishing the score early the following month. Though the family fortune (David Mason Greene, in his useful Greene’s Biographi- some critics faulted Prokofiev for overemphasizing the primitive qualities of cal Encyclopedia of Composers, described him as “a wastrel, a compulsive his folk materials with “barbaric” harmonies and “strident” sonorities, the gambler, a pathological liar, and a skirt chaser”), and by 1882 he had had quartet’s premiere, given in Moscow by the Beethoven Quartet on April 7, to sell off all of the estates to settle his debts.