Sergei Prokofiev, His Musical Life

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Spirits of the Age: Ghost Stories and the Victorian Psyche

SPIRITS OF THE AGE: GHOST STORIES AND THE VICTORIAN PSYCHE Jen Cadwallader A dissertation submitted to the faculty of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of English and Comparative Literature. Chapel Hill 2009 Approved by: Laurie Langbauer Jeanne Moskal Thomas Reinert Beverly Taylor James Thompson © 2009 Jen Cadwallader ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT JEN CADWALLADER: Spirits of the Age: Ghost Stories and the Victorian Psyche (Under the direction of Beverly Taylor) “Spirits of the Age: Ghost Stories and the Victorian Psyche” situates the ghost as a central figure in an on-going debate between nascent psychology and theology over the province of the psyche. Early in the nineteenth century, physiologists such as Samuel Hibbert, John Ferriar and William Newnham posited theories that sought to trace spiritual experiences to physical causes, a move that participated in the more general “attack on faith” lamented by intellectuals of the Victorian period. By mid-century, various of these theories – from ghosts as a form of “sunspot” to ghost- seeing as a result of strong drink – had disseminated widely across popular culture, and, I argue, had become a key feature of the period’s ghost fiction. Fictional ghosts provided an access point for questions regarding the origins and nature of experience: Ebenezer Scrooge, for example, must decide if he is being visited by his former business partner or a particularly nasty stomach disorder. The answer to this question, here and in ghost fiction across the period, points toward the shifting dynamic between spiritual and scientific epistemologies. -

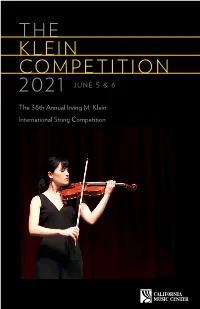

To Read Or Download the Competition Program Guide

THE KLEIN COMPETITION 2021 JUNE 5 & 6 The 36th Annual Irving M. Klein International String Competition TABLE OF CONTENTS Board of Directors Dexter Lowry, President Katherine Cass, Vice President Lian Ophir, Treasurer Ruth Short, Secretary Susan Bates Richard Festinger Peter Gelfand 2 4 5 Kevin Jim Mitchell Sardou Klein Welcome The Visionary The Prizes Tessa Lark Stephanie Leung Marcy Straw, ex officio Lee-Lan Yip Board Emerita 6 7 8 Judith Preves Anderson The Judges/Judging The Mentor Commissioned Works 9 10 11 Competition Format Past Winners About California Music Center Marcy Straw, Executive Director Mitchell Sardou Klein, Artistic Director for the Klein Competition 12 18 22 californiamusiccenter.org [email protected] Artist Programs Artist Biographies Donor Appreciation 415.252.1122 On the cover: 21 25 violinist Gabrielle Després, First Prize winner 2020 In Memory Upcoming Performances On this page: cellist Jiaxun Yao, Second Prize winner 2020 WELCOME WELCOME Welcome to the 36th Annual This year’s distinguished jury includes: Charles Castleman (active violin Irving M. Klein International performer/pedagogue and professor at the University of Miami), Glenn String Competition! This is Dicterow (former New York Philharmonic concertmaster and faculty the second, and we hope the member at the USC Thornton School of Music), Karen Dreyfus (violist, last virtual Klein Competition Associate Professor at the USC Thornton School of Music and the weekend. We have every Manhattan School of Music), our composer, Sakari Dixon Vanderveer, expectation that next June Daniel Stewart (Music Director of the Santa Cruz Symphony and Wattis we will be back live, with Music Director of the San Francisco Symphony Youth Orchestra), Ian our devoted audience in Swensen (Chair of the Violin Faculty at the San Francisco Conservatory attendance, at the San of Music), and Barbara Day Turner (Music Director of the San José Francisco Conservatory. -

Guest Artist Recital, Luby Symposium

2016 Luby Violin Symposium Guest Artist Recital Kevork Mardirossian, violin Lee Phillips, piano Wednesday, May 18, 2016 7:30 PM Person Recital Hall Program Sonata in D Major, HWV 371 (1681) George Frideric Handel Affetuoso (1685-1759) Allegro Larghetto Allegro Violin Sonata No. 2 in A Major, Op. 100 Johannes Brahms Allegro amabile (1833-97) Andante tranquilo – Vivace – Andante Allegretto grazioso Intermission Sonata No. 1 in G Minor for violin solo, BWV 1001 J.S. Bach Adagio (1685-1750) Fuga Suite Populaire Espagnole (1926) Manuel De Falla/arr. Paul Kochanski El paño moruno (1876-1946/1887-1934) Nana Canción Polo Asturiana Jota Tzigane (1924) Maurice Ravel (1875-1937) Special thanks to the UNC Summer School and Dean Jan Yopp, the UNC Music Department and Chair Louise Toppin, and Susan Klebanow. About the Luby Violin Symposium Named in honor of its founder, violinist and former UNC professor Richard Luby, the Symposium offers participants an intensive one-week immersion focused on individual instrumental and musical growth within the context of a supportive and nurturing atmosphere. Previously directed by Richard Luby and Fabian Lopez, the Symposium is in its eighth summer. The Symposium includes private lessons masterclasses student performances faculty performances guest artist performances HIP Bach perspectives body awareness methods practice techniques performance psychology All course activities take place on the beautiful campus at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in the Kenan Music Building and Person Hall. The Symposium is supported by the UNC Music Department, sponsored as a course by the UNC Summer School, and by donations which support student scholarships, activities, and artists. -

The Musical Partnership of Sergei Prokofiev And

THE MUSICAL PARTNERSHIP OF SERGEI PROKOFIEV AND MSTISLAV ROSTROPOVICH A CREATIVE PROJECT SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT FOR THE DEGREE MASTER OF MUSIC IN PERFORMANCE BY JIHYE KIM DR. PETER OPIE - ADVISOR BALL STATE UNIVERSITY MUNCIE, INDIANA DECEMBER 2011 Among twentieth-century composers, Sergei Prokofiev is widely considered to be one of the most popular and important figures. He wrote in a variety of genres, including opera, ballet, symphonies, concertos, solo piano, and chamber music. In his cello works, of which three are the most important, his partnership with the great Russian cellist Mstislav Rostropovich was crucial. To understand their partnership, it is necessary to know their background information, including biographies, and to understand the political environment in which they lived. Sergei Prokofiev was born in Sontovka, (Ukraine) on April 23, 1891, and grew up in comfortable conditions. His father organized his general education in the natural sciences, and his mother gave him his early education in the arts. When he was four years old, his mother provided his first piano lessons and he began composition study as well. He studied theory, composition, instrumentation, and piano with Reinhold Glière, who was also a composer and pianist. Glière asked Prokofiev to compose short pieces made into the structure of a series.1 According to Glière’s suggestion, Prokofiev wrote a lot of short piano pieces, including five series each of 12 pieces (1902-1906). He also composed a symphony in G major for Glière. When he was twelve years old, he met Glazunov, who was a professor at the St. -

95.3 Fm 95.3 Fm

October/NovemberMarch/April 2013 2017 VolumeVolume 41, 46, No. No. 3 1 !"#$%&'95.3 FM Brahms: String Sextet No. 2 in G, Op. 36; Marlboro Ensemble Saeverud: Symphony No. 9, Op. 45; Dreier, Royal Philharmonic WHRB Orchestra (Norwegian Composers) Mozart: Clarinet Quintet in A, K. 581; Klöcker, Leopold Quartet 95.3 FM Gombert: Missa Tempore paschali; Brown, Henry’s Eight Nielsen: Serenata in vano for Clarinet,Bassoon,Horn, Cello, and October-November, 2017 Double Bass; Brynildsen, Hannevold, Olsen, Guenther, Eide Pokorny: Concerto for Two Horns, Strings, and Two Flutes in F; Baumann, Kohler, Schröder, Concerto Amsterdam (Acanta) Barrios-Mangoré: Cueca, Aire de Zamba, Aconquija, Maxixa, Sunday, October 1 for Guitar; Williams (Columbia LP) 7:00 am BLUES HANGOVER Liszt: Grande Fantaisie symphonique on Themes from 11:00 am MEMORIAL CHURCH SERVICE Berlioz’s Lélio, for Piano and Orchestra, S. 120; Howard, Preacher: Professor Jonathan L. Walton, Plummer Professor Rickenbacher, Budapest Symphony Orchestra (Hyperion) of Christian Morals and Pusey Minister in The Memorial 6:00 pm MUSIC OF THE SOVIET UNION Church,. Music includes Kodály’s Missa brevis and Mozart’s The Eve of the Revolution. Ave verum corpus, K. 618. Scriabin: Sonata No. 7, Op. 64, “White Mass” and Sonata No. 9, 12:30 pm AS WE KNOW IT Op. 68, “Black Mass”; Hamelin (Hyperion) 1:00 pm CRIMSON SPORTSTALK Glazounov: Piano Concerto No. 2 in B, Op. 100; Ponti, Landau, 2:00 pm SUNDAY SERENADE Westphalian Orchestra of Recklinghausen (Turnabout LP) 6:00 pm HISTORIC PERFORMANCES Rachmaninoff: Vespers, Op. 37; Roudenko, Russian Chamber Prokofiev: Violin Concerto No. 2 in g, Op. -

UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title The Lyric Forms of the Literati Mind: Yosa Buson, Ema Saikō, Masaoka Shiki and Natsume Sōseki Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/97g9d23n Author Mewhinney, Matthew Stanhope Publication Date 2018 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California The Lyric Forms of the Literati Mind: Yosa Buson, Ema Saikō, Masaoka Shiki and Natsume Sōseki By Matthew Stanhope Mewhinney A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Japanese Language in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Alan Tansman, Chair Professor H. Mack Horton Professor Daniel C. O’Neill Professor Anne-Lise François Summer 2018 © 2018 Matthew Stanhope Mewhinney All Rights Reserved Abstract The Lyric Forms of the Literati Mind: Yosa Buson, Ema Saikō, Masaoka Shiki and Natsume Sōseki by Matthew Stanhope Mewhinney Doctor of Philosophy in Japanese Language University of California, Berkeley Professor Alan Tansman, Chair This dissertation examines the transformation of lyric thinking in Japanese literati (bunjin) culture from the eighteenth century to the early twentieth century. I examine four poet- painters associated with the Japanese literati tradition in the Edo (1603-1867) and Meiji (1867- 1912) periods: Yosa Buson (1716-83), Ema Saikō (1787-1861), Masaoka Shiki (1867-1902) and Natsume Sōseki (1867-1916). Each artist fashions a lyric subjectivity constituted by the kinds of blending found in literati painting and poetry. I argue that each artist’s thoughts and feelings emerge in the tensions generated in the process of blending forms, genres, and the ideas (aesthetic, philosophical, social, cultural, and historical) that they carry with them. -

Read Book Sergei Prokofiev Peter and Wolf Pdf Free Download

SERGEI PROKOFIEV PETER AND WOLF PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Sergei Prokofiev | 40 pages | 14 Sep 2004 | Random House USA Inc | 9780375824302 | English | New York, United States Sergei Prokofiev Peter and Wolf PDF Book Prokofiev had been considering making an opera out of Leo Tolstoy 's epic novel War and Peace , when news of the German invasion of the Soviet Union on 22 June made the subject seem all the more timely. This article contains a list of works that does not follow the Manual of Style for lists of works often, though not always, due to being in reverse-chronological order and may need cleanup. William F. You have entered an incorrect email address! The cat quickly climbs into the tree with the bird, but the duck, who has jumped out of the pond, is chased, overtaken, and swallowed by the wolf. Help Learn to edit Community portal Recent changes Upload file. To this day, elementary school children hear Peter and the Wolf during school assemblies or at concerts for young people. Merriam-Webster Dictionary. The Independent. However, Prokofiev was dissatisfied with the rhyming text produced by Antonina Sakonskaya, a then popular children's author. The Lives of Ingolf Dahl. Russian composer — Explore more from this episode More. Each character of this tale is represented by a corresponding instrument in the orchestra: the bird by a flute, the duck by an oboe, the cat by a clarinet playing staccato in a low register, the grandfather by a bassoon, the wolf by three horns, Peter by the string quartet, the shooting of the hunters by the kettle drums and bass drum. -

Nikolai Tcherepnin UNDER the CANOPY of MY LIFE Artistic, Creative, Musical Pedagogy, Public and Private

Nikolai Tcherepnin UNDER THE CANOPY OF MY LIFE Artistic, creative, musical pedagogy, public and private Translated by John Ranck But1 you are getting old, pick Flowers, growing on the graves And with them renew your heart. Nekrasov2 And ethereally brightening-within-me Beloved shadows arose in the Argentine mist Balmont3 The Tcherepnins are from the vicinity of Izborsk, an ancient Russian town in the Pskov province. If I remember correctly, my aged aunts lived on an estate there which had been passed down to them by their fathers and grandfathers. Our lineage is not of the old aristocracy, and judging by excerpts from the book of Records of the Nobility of the Pskov province, the first mention of the family appears only in the early 19th century. I was born on May 3, 1873 in St. Petersburg. My father, a doctor, was lively and very gifted. His large practice drew from all social strata and included literary luminaries with whom he collaborated as medical consultant for the gazette, “The Voice” that was published by Kraevsky.4 Some of the leading writers and poets of the day were among its editors. It was my father’s sorrowful duty to serve as Dostoevsky’s doctor during the writer’s last illness. Social activities also played a large role in my father’s life. He was an active participant in various medical societies and frequently served as chairman. He also counted among his patients several leading musical and theatrical figures. My father was introduced to the “Mussorgsky cult” at the hospitable “Tuesdays” that were hosted by his colleague, Dr. -

Sonata for Flute and Piano in D Major, Op. 94 by Sergey Prokofiev

SONATA FOR FLUTE AND PIANO IN D MAJOR, OP. 94 BY SERGEY PROKOFIEV: A PERFORMANCE GUIDE HONORS THESIS Presented to the Honors Committee of Texas State University-San Marcos in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for Graduation in the Honors ColLege by Danielle Emily Stevens San Marcos, Texas May 2014 1 SONATA FOR FLUTE AND PIANO IN D MAJOR, OP. 94 BY SERGEY PROKOFIEV: A PERFORMANCE GUIDE Thesis Supervisor: ________________________________ Kay Lipton, Ph.D. School of Music Second Reader: __________________________________ Adah Toland Jones, D. A. School of Music Second Reader: __________________________________ Cynthia GonzaLes, Ph.D. School of Music Approved: ____________________________________ Heather C. GaLLoway, Ph.D. Dean, Honors ColLege 2 Abstract This thesis contains a performance guide for Sergey Prokofiev’s Sonata for Flute and Piano in D Major, Op. 94 (1943). Prokofiev is among the most important Russian composers of the twentieth century. Recognized as a leading Neoclassicist, his bold innovations in harmony and his new palette of tone colors enliven the classical structures he embraced. This is especially evident in this flute sonata, which provides a microcosm of Prokofiev’s compositional style and highlights the beauty and virtuosic breadth of the flute in new ways. In Part 1 I have constructed an historical context for the sonata, with biographical information about Prokofiev, which includes anecdotes about his personality and behavior, and a discussion of the sonata’s commission and subsequent premiere. In Part 2 I offer an anaLysis of the piece with generaL performance suggestions and specific performance practice options for flutists that will assist them as they work toward an effective performance, one that is based on both the historically informed performance context, as well as remarks that focus on particular techniques, challenges and possible performance solutions. -

Abstracts Euromac2014 Eighth European Music Analysis Conference Leuven, 17-20 September 2014

Edited by Pieter Bergé, Klaas Coulembier Kristof Boucquet, Jan Christiaens 2014 Euro Leuven MAC Eighth European Music Analysis Conference 17-20 September 2014 Abstracts EuroMAC2014 Eighth European Music Analysis Conference Leuven, 17-20 September 2014 www.euromac2014.eu EuroMAC2014 Abstracts Edited by Pieter Bergé, Klaas Coulembier, Kristof Boucquet, Jan Christiaens Graphic Design & Layout: Klaas Coulembier Photo front cover: © KU Leuven - Rob Stevens ISBN 978-90-822-61501-6 A Stefanie Acevedo Session 2A A Yale University [email protected] Stefanie Acevedo is PhD student in music theory at Yale University. She received a BM in music composition from the University of Florida, an MM in music theory from Bowling Green State University, and an MA in psychology from the University at Buffalo. Her music theory thesis focused on atonal segmentation. At Buffalo, she worked in the Auditory Perception and Action Lab under Peter Pfordresher, and completed a thesis investigating metrical and motivic interaction in the perception of tonal patterns. Her research interests include musical segmentation and categorization, form, schema theory, and pedagogical applications of cognitive models. A Romantic Turn of Phrase: Listening Beyond 18th-Century Schemata (with Andrew Aziz) The analytical application of schemata to 18th-century music has been widely codified (Meyer, Gjerdingen, Byros), and it has recently been argued by Byros (2009) that a schema-based listening approach is actually a top-down one, as the listener is armed with a script-based toolbox of listening strategies prior to experiencing a composition (gained through previous style exposure). This is in contrast to a plan-based strategy, a bottom-up approach which assumes no a priori schemata toolbox. -

Information to Users

INFORMATION TO USERS While the most advanced technology has been used to photograph and reproduce this manuscript, the quality of the reproduction is heavily dependent upon the quality of the material submitted. For example: • Manuscript pages may have indistinct print. In such cases, the best available copy has been filmed. • Manuscripts may not always be complete. In such cases, a note will indicate that it is not possible to obtain missing pages. • Copyrighted material may have been removed from the manuscript. In such cases, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, and charts) are photographed by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand corner and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each oversize page is also filmed as one exposure and is available, for an additional charge, as a standard 35mm slide or as a 17”x 23” black and white photographic print. Most photographs reproduce acceptably on positive microfilm or microfiche but lack the clarity on xerographic copies made from the microfilm. For an additional charge, 35mm slides of 6”x 9” black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations that cannot be reproduced satisfactorily by xerography. Order Number 8726582 Chiang Wen-Yeh: The style of his selected piano works and a study of music modernization in Japan and China Kuo, Tzong-Kai, D.M.A. The Ohio State University, 1987 Copyright ©1987 by Kuo, Tzong-Kai. All rights reserved. UMI 300 N. ZeebRd. Ann Arbor, MI 48106 CHIANG WEN-YEH: THE STYLE OF HIS SELECTED PIANO WORKS AND A STUDY OF MUSIC MODERNIZATION IN JAPAN AND CHINA DMA. -

Program Notes by Dr

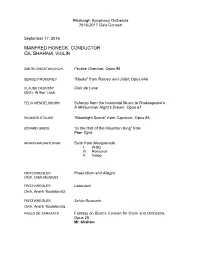

Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra 2016-2017 Gala Concert September 17, 2016 MANFRED HONECK, CONDUCTOR GIL SHAHAM, VIOLIN DMITRI SHOSTAKOVICH Festive Overture, Opus 96 SERGEI PROKOFIEV “Masks” from Romeo and Juliet, Opus 64a CLAUDE DEBUSSY Clair de Lune Orch. Arthur Luck FELIX MENDELSSOHN Scherzo from the Incidental Music to Shakespeare’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream, Opus 61 RICHARD STAUSS “Moonlight Scene” from Capriccio, Opus 85 EDVARD GREIG “In the Hall of the Mountain King” from Peer Gynt ARAM KHACHATURIAN Suite from Masquerade I. Waltz IV. Romance V. Galop FRITZ KREISLER Praeludium and Allegro Orch. Clark McAlister FRITZ KREISLER Liebesleid Orch. André Kostelanetz FRITZ KREISLER Schön Rosmarin Orch. André Kostelanetz PABLO DE SARASATE Fantasy on Bizet’s Carmen for Violin and Orchestra, Opus 25 Mr. Shaham Sept. 17, 2016, page 1 PROGRAM NOTES BY DR. RICHARD E. RODDA DMITRI SHOSTAKOVICH (1906-1975) Festive Overture, Opus 96 (1954) Among the grand symphonies, concertos, operas and chamber works that Dmitri Shostakovich produced are also many occasional pieces: film scores, tone poems, jingoistic anthems, brief instrumental compositions. Though most of these works are unfamiliar in the West, one — the Festive Overture — has been a favorite since it was written in the autumn of 1954. Shostakovich composed it for a concert on November 7, 1954 commemorating the 37th anniversary of the Russian Revolution, but its jubilant nature suggests it may also have been conceived as an outpouring of relief at the death of Joseph Stalin one year earlier. One critic suggested that the Overture was “a gay picture of streets and squares packed with a young and happy throng.” As its title suggests, the Festive Overture is a brilliant affair, full of fanfare and bursting spirits.