Re-Establishing Context for Orphaned Collections a Case Study from the Market Street Chinatown, San Jose, California

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SAN JOSE Food Works FOOD SYSTEM CONDITIONS & STRATEGIES for a MORE VIBRANT RESILIENT CITY

SAN JOSE Food Works FOOD SYSTEM CONDITIONS & STRATEGIES FOR A MORE VIBRANT RESILIENT CITY NOV 2016 Food Works SAN JOSE Food Works ■ contents Executive Summary 2 Farmers’ markets 94 Background and Introduction 23 Food E-Commerce Sector 96 San Jose Food System Today 25 Food and Agriculture IT 98 Economic Overview 26 Food and Agriculture R & D 101 Geographic Overview 41 Best Practices 102 San Jose Food Sector Actors and Activities 47 Summary of Findings, Opportunities, 116 County and Regional Context 52 and Recommendations Food Supply Chain Sectors 59 APPENDICES Production 60 A: Preliminary Assessment of a San Jose 127 Market District/ Wholesale Food Market Distribution 69 B: Citywide Goals and Strategies 147 Processing 74 C: Key Reports 153 Retail 81 D: Food Works Informants 156 Restaurants and Food Service 86 End Notes 157 Other Food Sectors 94 PRODUCED BY FUNDED BY Sustainable Agriculture Education (SAGE) John S. and James L. Knight Foundation www.sagecenter.org 11th Hour Project in collaboration with San Jose Department of Housing BAE Urban Economics Santa Clara Valley Open Space Authority www.bae1.com 1 San Jose Executive Summary What would San Jose look like if a robust local food system was one of the vital frameworks linking the city’s goals for economic development, community health, environmental stewardship, culture, and identity as the City’s population grows to 1.5 million people over the next 25 years? he Food Works report answers this question. The team engaged agencies, businesses, non- T profits and community groups over the past year in order to develop this roadmap for making San Jose a vibrant food city and a healthier, more resilient place. -

Objects Collapse Time. Through Archaeology, the Unreachable Past Becomes Tangible Again. in This Way, Archaeology Mitigates

Chinese Historical and Cultural Project was founded in 1987, shortly after discovery of the Market Street Chinatown artifacts in 1985. Through a long process, the 400 boxes of artifacts recovered from the Market Street Chinatown were eventually brought to History San José, and then loaned to Stanford University for their archaeology program. We were so pleased because otherwise all those artifacts would still be sitting there, without being seen or touched. City Beneath the City brings to the forefront that there were Chinese here in early San Jose. There were actually five Chinatowns in San Jose, and today there are none. This exhibition is, in a way, an extension of Chinese Historical and Cultural Project’s work to promote education by displaying the culture and the history of the early Chinese immigrants and Chinese Americans in Santa Clara Valley. Both at the Chinese American History Museum at History Park and in a travelling exhibit that is displayed in libraries and other public buildings throughout Santa Clara County, we are trying to share our culture and our history and the contributions we have made. Anita Kwock, Technology Resource Teacher, San Jose Unified School District President, Chinese Historical and Cultural Project The French Jesuit scholar Michel de Certeau once described urban spaces as “haunted.” More than present-day centers of commerce and industry, our cities must be experienced imaginatively through the stories and legends that metaphorically inhabit them. The streets of a city “offer to store up rich silences and wordless stories,” according to de Certeau. City Beneath the City is not an exhibition of objects from a lost city, but an exhibition of the stories these objects tell – past, present, and future. -

UC Riverside Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC Riverside UC Riverside Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Migration, Social Network, and Identity: The Evolution of Chinese Community in East San Gabriel Valley, 1980-2010 Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/8c60v1bm Author Hung, Yu-Ju Publication Date 2013 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA RIVERSIDE Migration, Social Network, and Identity: The Evolution of Chinese Community in East San Gabriel Valley, 1980-2010 A Dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History by Yu-Ju Hung August 2013 Dissertation Committee: Dr. Clifford Trafzer, Chairperson Dr. Larry Burgess Dr. Rebecca Monte Kugel Copyright by Yu-Ju Hung 2013 The Dissertation of Yu-Ju Hung is approved: ____________________________________________ ___________________________________________ ___________________________________________ Committee Chairperson University of California, Riverside Acknowledgements This dissertation would hardly have possible without the help of many friends and people. I would like to express deepest gratitude to my advisor, Professor Clifford Trafzer, who gave me boundless patience and time for my doctoral studies. His guidance and instruction not only inspired me in the dissertation research but also influenced my interests in academic pursuits. I want to thank other committee members: Professor Larry Burgess and Professor Rebecca Monte Kugel. Both of them provided thoughtful comments and valuable ideas for my dissertation. I am also indebted to Tony Yang, for his painstaking editing and proofreading work during my final writing stage. My special thanks go to Professor Chin-Yu Chen, for her constant concern and insightful suggestions for my research. -

Federal Reserve Banks

Skip to Content Release dates Current release Other formats: ASCII | PDF (51 KB) MINORITY OWNED DEPOSITORY INSTITUTIONS and THEIR BRANCHES as of June 30, 2015 State of CALIFORNIA - ( Assets and Deposits in Thousands ) Holding Minority Company Established Institution/Branch Name Location ID Chtr Class Ent Type Min Cd Ownership Assets Deposits Dt Name Dt AMERICAN CONTINENTAL BK , ARCADIA BR ARCADIA, CA 4580694 3/31/2015 9/23/2013 AMERICAN CONTINENTAL BK , CHINO HILLS BR CHINO HILLS, CA 4201690 3/31/2015 3/6/2008 AMERICAN CONTINENTAL BK , SAN GABRIEL BR SAN GABRIEL, CA 3553570 3/31/2015 10/23/2006 AMERICAN PLUS BK NA ARCADIA, CA 3623110 117 NAT 20 11/1/2008 8/8/2007 $327,835 $253,082 AMERICAN PLUS BK NA , PASADENA BR PASADENA, CA 4852403 8/27/2014 8/27/2014 ROWLAND AMERICAN PLUS BK NA , ROWLAND HGTS BR 4094173 8/15/2009 8/15/2009 HEIGHTS, CA AMERICAS UNITED BK GLENDALE, CA 3488980 207 NMB 10 1/11/2007 11/6/2006 $169,328 $138,980 AMERICAS UNITED BK , DOWNEY BR DOWNEY, CA 4435963 12/30/2010 12/30/2010 AMERICAS UNITED BK , GLENDALE BR GLENDALE, CA 4811295 12/31/2012 12/31/2012 AMERICAS UNITED BK , LANCASTER BR LANCASTER, CA 87962 3/28/2014 3/31/1967 ASIAN PACIFIC NB SAN GABRIEL, CA 1462986 117 NAT 20 2/3/2004 7/25/1990 $55,888 $46,725 ROWLAND ASIAN PACIFIC NB , ROWLAND HGTS RGNL OFF 2641854 2/3/2004 12/3/1997 HEIGHTS, CA SAN FRANCISCO, BANK OF THE ORIENT 777366 217 SMB ORIENT BC 20 9/22/1992 3/17/1971 $457,627 $384,792 CA BANK OF THE ORIENT , MILLBRAE BR MILLBRAE, CA 2961682 11/15/1999 11/15/1999 BANK OF THE ORIENT , OAKLAND BR OAKLAND, CA -

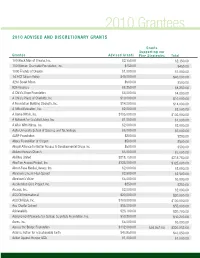

2010 Grantees 2010 Advised and Discretionary Grants

2010 Grantees 2010 Advised And discretionAry GrAnts Grants supporting our Grantee Advised Grants Five strategies total 100 Black Men of Omaha, Inc. $2,350.00 $2,350.00 100 Women Charitable Foundation, Inc. $450.00 $450.00 1000 Friends of Oregon $1,000.00 $1,000.00 1st ACT Silicon Valley $40,000.00 $40,000.00 42nd Street Moon $500.00 $500.00 826 Valencia $8,250.00 $8,250.00 A Child’s Hope Foundation $4,000.00 $4,000.00 A Child’s Place of Charlotte, Inc. $10,000.00 $10,000.00 A Foundation Building Strength, Inc. $14,000.00 $14,000.00 A Gifted Education, Inc. $2,000.00 $2,000.00 A Home Within, Inc. $105,000.00 $105,000.00 A Network for Grateful Living, Inc. $1,000.00 $1,000.00 A Wish With Wings, Inc. $2,000.00 $2,000.00 Aalto University School of Science and Technology $6,000.00 $6,000.00 AARP Foundation $200.00 $200.00 Abbey Foundation of Oregon $500.00 $500.00 Abigail Alliance for Better Access to Developmental Drugs Inc $500.00 $500.00 Abilene Korean Church $3,000.00 $3,000.00 Abilities United $218,750.00 $218,750.00 Abortion Access Project, Inc. $325,000.00 $325,000.00 About-Face Media Literacy, Inc. $2,000.00 $2,000.00 Abraham Lincoln High School $2,500.00 $2,500.00 Abraham’s Vision $5,000.00 $5,000.00 Accelerated Cure Project, Inc. $250.00 $250.00 Access, Inc. $2,000.00 $2,000.00 ACCION International $20,000.00 $20,000.00 ACCION USA, Inc. -

October 2016

Saratoga Historical Foundation PO Box 172, Saratoga CA 95071 October 2016 Support the October 15 Saratoga Historical Foundation Estate Sale Today!!!! Celebrate India Showcase! October 23 Time to Shop—It’s An Estate Sale! Celebrate India Showcase The Saratoga Historical Foundation will be holding an For the second year, the Saratoga Historical estate sale on Saturday October 15 from 9 to 3 PM. Foundation is hosting the India Showcase at the Grab your wallet and come on by and find a treasure Saratoga History Museum October 23 from 1-4 PM or two. and is free to the public. According to Fund Development Director Bob Himel The event will include Asian Indian arts and crafts, the estate sale has a big selection of vintage jewelry, food, dance demonstration, music, and more. collectible artwork, antiques, garden items, plants, According to Event Coordinator Rina Shah, “the kitchenware, and more. our Donations!!event will include classical folk, Bollywood and other Funds from the estate sale will be used to construct a dances by five groups: Shilpa Padwekar, Saratoga blacksmith exhibit located at the Saratoga Historical High School Bollywood dance group, Sanjana, Park. The educational exhibit will showcase the Saratoga adult dance group, and Priya Krishnamurth’s museum's collection of farm and timber tools. The dance group.” interactive exhibit will also include sound effects. Other activities include Kailash Ranganathan with The fundraiser will run from 9 AM to 3 PM on the instrumental music on the sitar. Bela Desai will sing museum's patio at 20450 Saratoga-Los Gatos Road inhere! traditional songs. -

A RTAN DAILY About the War on the Cards

n a t her inis- oca t- ;to te SEA ND THE WAR' ;ain- ages Obituary Vietnam Day Talks vide GONE. TO GR AV EYARDS EVERYONE The following is a "do-it-yourself ()Wittily for all those male SJS students who have died or will die lAii-11-N WILL I HEY I VER LEARN To Seek Solutions in Vietnam in the coming years. Bs. RA I' 1:II.Es and CANIW BELL lessor of psychology, will discuss "Dis- The game is simple. just fill in the appropriate Daily Political Writers sent and Commitment" in the Pacifica of the people, by Room. Dr. Richard Kilby. professor names and dates iii the spaces provided. A demonstration, the people, and for the people, starts of psychology, will discuss "American Marine Cpl. was killed in Vietnam today at 10:30. Military Involvement --How Much and Although President Richard Nixon How Long?" in the Guadalupe Room. , 19 when the truck in which has said, "To allow government policy "Billions for Defense, Peanuts for he was riding struck an enemy mine north of ()ming to be made in the streets would destroy Cities" is the topic in the Costanoan the democratic process," most SJS Room with Dr. William Garvey, from Nam Province students, faculty, and administrators the student counseling service, mod- erating. Dr. Frederic Weed, professor son of Mr. and Mrs. feel strongly that today's convocation is a proper democratic way to express of political science, will discuss "Dis- of , was a 19 graduate of their concern over U.S. involvement sent and the Constitutfan" in the Cala- High School. -

Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders in California, 1850-1970 MPS

UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES EVALUATION/RETURN SHEET Requested Action: COVER DOCUMENTATION Multiple Name: Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders in California, 1850-1970 MPS State & County: CALIFORNIA, San Francisco Date Received: Date of 45th Day: 11/29/2019 1/13/2020 Reference MC100004867 number: Reason For Review: Checkbox: Unchecked Appeal Checkbox:PDIL Unchecked Checkbox:Text/Data Issue Unchecked Checkbox: Unchecked SHPO Request LandscapeCheckbox: Unchecked PhotoCheckbox: Unchecked Checkbox: Unchecked Waiver Checkbox:National Unchecked Checkbox:Map/Boundary Unchecked Checkbox: Unchecked Resubmission Checkbox:Mobile Resource Unchecked PeriodCheckbox: Unchecked Checkbox:Other Unchecked Checkbox:TCP Unchecked Checkbox:Less than 50 Unchecked years CLGCheckbox: Unchecked Checkbox: Checked Accept ReturnCheckbox: Unchecked Checkbox:Reject Unchecked 1/10/2020 Date Abstract/Summary The Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders in California, 1850-1970 MPS cover document is Comments: an excellent resource for the evaluation, documentation and designation of historic ethnic resources in California. The MPS develops three fairly comprehensive thematic contexts and provides registration guidelines for several general and specific property types including historic districts, agricultural properties, industrial sites, community service properties, religious properties and properties associated with significant individuals. Additional contexts, time periods, and associated property types may be developed at a later date. NPS grant funded project. Recommendation/ Accept MPS Cover Documentation Criteria Reviewer Paul Lusignan Discipline Historian Telephone (202)354-2229 Date 1/10/2020 DOCUMENTATION: see attached comments: No see attached SLR: Yes If a nomination is returned to the nomination authority, the nomination is no longer under consideration by the National Park Service. NPS Form 10-900-a (Rev. -

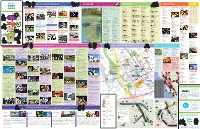

Getting Around Downtown and the Bay Area San Jose

Visit sanjose.org for the Taste wines from mountain terrains and cooled by ocean Here is a partial list of accommodations. Downtown is a haven for the SAN JOSE EVENTS BY THE SEASONS latest event information REGIONAL WINES breezes in one of California’s oldest wine regions WHERE TO STAY For a full list, please visit sanjose.org DOWNTOWN DINING hungry with 250+ restaurants WEATHER San Jose enjoys on average Santa Clara County Fair Antique Auto Show There are over 200 vintners that make up the Santa Cruz Mountain wine AIRPORT AREA - NORTH Holiday Inn San Jose Airport Four Points by Sheraton SOUTH SAN JOSE American/Californian M Asian Fusion Restaurant Gordon Biersch Brewery 300 days of sunshine. LEAGUE SPORTS YEAR ROUND MAY July/August – thefair.org Largest show on the West coast appellation with roots that date back to the 1800s. The region spans from 1350 N. First St. San Jose Downtown 98 S. 2nd Street Restaurant Best Western Plus Clarion Inn Silicon Valley Billy Berk’s historysanjose.org Mt. Madonna in the south to Half Moon Bay in the north. The mountain San Jose, CA 95112 211 S. First St. (408) 418-2230 – $$ 33 E. San Fernando St. Our average high is 72.6˚ F; San Jose Sabercats (Arena Football) Downtown Farmer’s Market Summer Kraftbrew Beer Fest 2118 The Alameda 3200 Monterey Rd. 99 S. 1st St. Japantown Farmer’s Market terrain, marine influences and varied micro-climates create the finest (408) 453-6200 San Jose, CA 95113 (408) 294-6785 – $$ average low is 50.5˚ F. -

Chinese Americans

06-Min-4720.qxd 5/20/2005 9:30 PM Page 110 6 Chinese Americans MORRISON G. WONG n 2000, the Chinese were the largest of more occupational adjustments to American society. Ithan 20 Asian groups residing in the United The unique social structure and problems of States. A diverse group, both culturally and on the Chinatown are the topic of the fifth section. This basis of national origins,the Chinese include those chapter concludes by looking at the future accul- born in the United States and who have been resid- turation of the Chinese in the United States. ing here for several generations, as well as those born abroad in China, Taiwan, Hong Kong, IMMIGRATION AND Vietnam, and in other countries and who have DISCRIMINATORY MEASURES been residing here for much shorter periods of time. The history of the Chinese in the United The Chinese were the first Asian group to immi- States over the past 150 years is characterized grate in significant numbers to the United States. by episodes of prejudice and discrimination; Although only 43 Chinese resided in the United of racism, xenophobia, and exclusion; and, more States prior to 1850, the discovery of gold in recently,of contrasting and varying degrees of sus- California in 1848 initiated a dramatic and signif- picion, tolerance, or acceptance. This chapter, icant influx of Chinese immigrants. In the next divided into six distinct but interrelated and inter- three decades, over 225,000 Chinese immigrated twined sections, presents a sociohistory of the to the United States. About 90% of the early Chinese in the United States. -

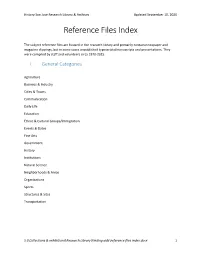

Reference Files Index

History San Jose Research Library & Archives Updated September 10, 2020 Reference Files Index The subject reference files are housed in the research library and primarily contain newspaper and magazine clippings, but in some cases unpublished typescripts/manuscripts and presentations. They were compiled by staff and volunteers circa 1970-2015. I. General Categories Agriculture Business & Industry Cities & Towns Communication Daily Life Education Ethnic & Cultural Groups/Immigration Events & Dates Fine Arts Government History Institutions Natural Science Neighborhoods & Areas Organizations Sports Structures & Sites Transportation S:\\Collections & exhibitions\Research Library\Finding aids\reference files index.docx 1 History San Jose Research Library & Archives Updated September 10, 2020 II. Sub-headings within categories Agriculture o General (includes honeybees) o Aquaculture o Canneries . Mayfair Packing Corporation . Prunes o Dairies . Claravale Dairy o Farmers’ Union o Floriculture o Horticulture o Livestock o Poultry (includes ostrich farms) o Viniculture (Wine) Business & Industry o General o Banking & Financial Services o Breweries o Construction o Electronics Industry o Employment o Manufacturing . General . Auto . Electronic . FMC . IBM . Kaiser . Lockheed o Organized Crime o Paper Mill (Lick) o Quarrying & Mining o Real Estate . Google/Adobe . Development/Redevelopment o Retail . General . Bookstores . Department Stores . Food Products . Grocery Stores S:\\Collections & exhibitions\Research Library\Finding aids\reference files -

Silicon Valley Rapid Transit Corridor Eis/Eir

SANTA CLARA VALLEY TRANSPORTATION AUTHORITY (VTA) SILICON VALLEY RAPID TRANSIT CORRIDOR EIS/EIR DRAFT Technical Memorandum Historical Resources Evaluation Report for SVRTC EIS/EIR Alternatives Prepared by JRP Historical Consulting Services 1490 Drew Ave., Suite 110 Davis, CA 95616 January 2003 JRP Historical Consulting Services Table of Contents EXECTIVE SUMMARY ............................................................................................................ iii 1. INTRODUCTION ...............................................................................................................1 1.1. PROJECT ALTERNATIVES.................................................................................................. 1 2. RESEARCH AND FIELD METHODS.............................................................................3 2.1. PREPARERS’ QUALIFICATIONS ......................................................................................... 5 3. HISTORICAL OVERVIEW ..............................................................................................7 3.1. INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................ 7 3.2. EARLY HISTORY OF SANTA CLARA AND SOUTHERN ALAMEDA COUNTY: 1769-1848..... 7 3.2.1. Spanish Period: 1769 to 1822 .................................................................................... 7 3.2.2. Mexican Period: 1822 to 1848................................................................................... 8 3.3. SANTA CLARA COUNTY