Immigration, Acculturation, and Quality of Life: a Study Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Department/Proposal AIRPORT CAPITAL IMPVT

Special/Capital Fund Clean-Up Actions Annual Report 2010-2011 USE SO.URCE NET COST Personal Non-Personal/ Ending Fund Total Beg Fund Department/Proposal Services Equipment Other Balance Use Revenue Balance AIRPORT CAPITAL IMPVT FUND (520) ~irport Capital Program Fund Balance Reconciliation $65,492 $65,492 $65,492 $0 Rebudget: Taxiway W Improvements $35,000 ($35,000) $o Total AIRPORT CAPITAL IMPVT FUND (520) S0 $0 $35,000 $30,492 $65,492 $0 $65,492 $0 AIRPORT CUST FAC & TRANS FD (519) ~IRPORT Fund Balance Reconciliation - OPEB $301 $301 $301 $0 Fund Balance Reconciliation - Rate Stabilization Reserve $1,908,093 $1,908,093 $1,908,093 Total AIRPORT CUST FAC & TRANS FD (519) S0 $1,908,394 $0 $1,908,394 $0 $1,908,394 $0 AIRPORT FISCAL AGENT FUND (525) AIRPORT Fund Balance Reconciliation $2,658,037 $2,658,037 $2,658,037 $o Total AIRPORT FISCAL AGENT FUND (525) S0 $0 $2,658,037 $2,658,037 $0 $2,658,037 $0 AIRPORT MAINT & OPER FUND (523) CITY MANAGER Retirement Contributions Reconciliation ($316) $316 $o $o Unemployment Insurance Reconciliation ($395) $395 CITY ATTORNEY Retirement Contributions Reconciliation ($2,972) $2,972 $o $0 Unemployment Insurance Reconciliation ($3,711) $3,711 POLICE Retirement Contributions Reconciliation ($469) $469 $0 $0 Sp ecial/Capital Fund Clean-Up Actions Annual Report 2010-2011 USE SOURCE NET COST Personal Non-Personal! Ending Fund Total Beg Fund Department/Proposal Services Equipment Other Balance Use Revenue. Balance AIRPORT MAINT & OPER FUND (523) ~OLICE Unemployment Insurance Reconciliation ($589) $589 $o Retirement -

SAN JOSE Food Works FOOD SYSTEM CONDITIONS & STRATEGIES for a MORE VIBRANT RESILIENT CITY

SAN JOSE Food Works FOOD SYSTEM CONDITIONS & STRATEGIES FOR A MORE VIBRANT RESILIENT CITY NOV 2016 Food Works SAN JOSE Food Works ■ contents Executive Summary 2 Farmers’ markets 94 Background and Introduction 23 Food E-Commerce Sector 96 San Jose Food System Today 25 Food and Agriculture IT 98 Economic Overview 26 Food and Agriculture R & D 101 Geographic Overview 41 Best Practices 102 San Jose Food Sector Actors and Activities 47 Summary of Findings, Opportunities, 116 County and Regional Context 52 and Recommendations Food Supply Chain Sectors 59 APPENDICES Production 60 A: Preliminary Assessment of a San Jose 127 Market District/ Wholesale Food Market Distribution 69 B: Citywide Goals and Strategies 147 Processing 74 C: Key Reports 153 Retail 81 D: Food Works Informants 156 Restaurants and Food Service 86 End Notes 157 Other Food Sectors 94 PRODUCED BY FUNDED BY Sustainable Agriculture Education (SAGE) John S. and James L. Knight Foundation www.sagecenter.org 11th Hour Project in collaboration with San Jose Department of Housing BAE Urban Economics Santa Clara Valley Open Space Authority www.bae1.com 1 San Jose Executive Summary What would San Jose look like if a robust local food system was one of the vital frameworks linking the city’s goals for economic development, community health, environmental stewardship, culture, and identity as the City’s population grows to 1.5 million people over the next 25 years? he Food Works report answers this question. The team engaged agencies, businesses, non- T profits and community groups over the past year in order to develop this roadmap for making San Jose a vibrant food city and a healthier, more resilient place. -

Objects Collapse Time. Through Archaeology, the Unreachable Past Becomes Tangible Again. in This Way, Archaeology Mitigates

Chinese Historical and Cultural Project was founded in 1987, shortly after discovery of the Market Street Chinatown artifacts in 1985. Through a long process, the 400 boxes of artifacts recovered from the Market Street Chinatown were eventually brought to History San José, and then loaned to Stanford University for their archaeology program. We were so pleased because otherwise all those artifacts would still be sitting there, without being seen or touched. City Beneath the City brings to the forefront that there were Chinese here in early San Jose. There were actually five Chinatowns in San Jose, and today there are none. This exhibition is, in a way, an extension of Chinese Historical and Cultural Project’s work to promote education by displaying the culture and the history of the early Chinese immigrants and Chinese Americans in Santa Clara Valley. Both at the Chinese American History Museum at History Park and in a travelling exhibit that is displayed in libraries and other public buildings throughout Santa Clara County, we are trying to share our culture and our history and the contributions we have made. Anita Kwock, Technology Resource Teacher, San Jose Unified School District President, Chinese Historical and Cultural Project The French Jesuit scholar Michel de Certeau once described urban spaces as “haunted.” More than present-day centers of commerce and industry, our cities must be experienced imaginatively through the stories and legends that metaphorically inhabit them. The streets of a city “offer to store up rich silences and wordless stories,” according to de Certeau. City Beneath the City is not an exhibition of objects from a lost city, but an exhibition of the stories these objects tell – past, present, and future. -

Historic Resource Project Assessment Cityview Plaza (A.K.A

Historic Resource Project Assessment CityView Plaza (a.k.a. Park Center Plaza) 150 Almaden Blvd. (+additional addresses) San José, Santa Clara County, California (APNs #259-41-054, -057, -066, -067, -068, and -070) Archives & Architecture photo / November 2019 Prepared for: City of San José Department of Planning, Building & Code Enforcement C/o David J. Powers & Associates, Inc. 1871 The Alameda Suite 200 San José, CA 95126 12.18.2019 (revised 02.07.2020) ARCHIVES & ARCHITECTURE, LLC PO Box 1332 San José, CA 95109-1332 http://www.archivesandarchitecture.com Historic Resource Project Assessment Table of Contents Table of Contents Table of Contents ........................................................................................................................... 2 Introduction ..................................................................................................................................... 3 Project Description...................................................................................................................... 4 Purpose and Methodology of this Study ..................................................................................... 4 Previous Surveys and Historical Status ...................................................................................... 5 Location Map .............................................................................................................................. 6 Summary of Findings ................................................................................................................. -

African American Community Service Agency Event

African American Community Service Agency Event: Juneteenth Grant will support the 39th Juneteenth Festival on June 20, 2020 at the Plaza de Cesar Chavez in downtown San Jose. Juneteenth recognizes the emancipation of slaves in the United States and is celebrated annually in more than 200 cities across the country. The event includes music, ethnic food, dance, and art for all ages. Aimusic School Event: Aimusic International Festival Grant will support the Aimusic International Festival: Intangible Chinese Heritage Celebration on April 25 through May 2, 2020 at San Jose Community College, California Theater, and San Jose State University. The festival promotes traditional Chinese music and performing arts. Almaden Valley Women's Club Event: Almaden Valley Art and Wine Festival Grant will support the 43rd annual Almaden Valley Art and Wine Festival on September 15, 2019 at Almaden Lake Park. The festival includes juried arts and crafts with over 90 artists, international food, local entertainment, and a children’s area of arts, crafts, and sports activities. Asian American Center of Santa Clara County (AASC) Event: Santa Clara County Fairgrounds TET Festival Grant request to support the 38th annual TET festival at the Santa Clara County Fairgrounds on January 25 and 26, 2020. The event celebrates the lunar new year, preserves, and promotes Vietnamese culture, raises funds for under-privileged youth and encourages youth leadership development and community involvement. Bay Area Cultural Connections (BayCC) Event: International Children’s Festival Grant will support the International Children’s Festival in April 2020 at Discovery Meadow Park in San Jose. The festival has been organized as a flagship event which brings families of different cultures together. -

UC Riverside Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC Riverside UC Riverside Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Migration, Social Network, and Identity: The Evolution of Chinese Community in East San Gabriel Valley, 1980-2010 Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/8c60v1bm Author Hung, Yu-Ju Publication Date 2013 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA RIVERSIDE Migration, Social Network, and Identity: The Evolution of Chinese Community in East San Gabriel Valley, 1980-2010 A Dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History by Yu-Ju Hung August 2013 Dissertation Committee: Dr. Clifford Trafzer, Chairperson Dr. Larry Burgess Dr. Rebecca Monte Kugel Copyright by Yu-Ju Hung 2013 The Dissertation of Yu-Ju Hung is approved: ____________________________________________ ___________________________________________ ___________________________________________ Committee Chairperson University of California, Riverside Acknowledgements This dissertation would hardly have possible without the help of many friends and people. I would like to express deepest gratitude to my advisor, Professor Clifford Trafzer, who gave me boundless patience and time for my doctoral studies. His guidance and instruction not only inspired me in the dissertation research but also influenced my interests in academic pursuits. I want to thank other committee members: Professor Larry Burgess and Professor Rebecca Monte Kugel. Both of them provided thoughtful comments and valuable ideas for my dissertation. I am also indebted to Tony Yang, for his painstaking editing and proofreading work during my final writing stage. My special thanks go to Professor Chin-Yu Chen, for her constant concern and insightful suggestions for my research. -

Federal Reserve Banks

Skip to Content Release dates Current release Other formats: ASCII | PDF (51 KB) MINORITY OWNED DEPOSITORY INSTITUTIONS and THEIR BRANCHES as of June 30, 2015 State of CALIFORNIA - ( Assets and Deposits in Thousands ) Holding Minority Company Established Institution/Branch Name Location ID Chtr Class Ent Type Min Cd Ownership Assets Deposits Dt Name Dt AMERICAN CONTINENTAL BK , ARCADIA BR ARCADIA, CA 4580694 3/31/2015 9/23/2013 AMERICAN CONTINENTAL BK , CHINO HILLS BR CHINO HILLS, CA 4201690 3/31/2015 3/6/2008 AMERICAN CONTINENTAL BK , SAN GABRIEL BR SAN GABRIEL, CA 3553570 3/31/2015 10/23/2006 AMERICAN PLUS BK NA ARCADIA, CA 3623110 117 NAT 20 11/1/2008 8/8/2007 $327,835 $253,082 AMERICAN PLUS BK NA , PASADENA BR PASADENA, CA 4852403 8/27/2014 8/27/2014 ROWLAND AMERICAN PLUS BK NA , ROWLAND HGTS BR 4094173 8/15/2009 8/15/2009 HEIGHTS, CA AMERICAS UNITED BK GLENDALE, CA 3488980 207 NMB 10 1/11/2007 11/6/2006 $169,328 $138,980 AMERICAS UNITED BK , DOWNEY BR DOWNEY, CA 4435963 12/30/2010 12/30/2010 AMERICAS UNITED BK , GLENDALE BR GLENDALE, CA 4811295 12/31/2012 12/31/2012 AMERICAS UNITED BK , LANCASTER BR LANCASTER, CA 87962 3/28/2014 3/31/1967 ASIAN PACIFIC NB SAN GABRIEL, CA 1462986 117 NAT 20 2/3/2004 7/25/1990 $55,888 $46,725 ROWLAND ASIAN PACIFIC NB , ROWLAND HGTS RGNL OFF 2641854 2/3/2004 12/3/1997 HEIGHTS, CA SAN FRANCISCO, BANK OF THE ORIENT 777366 217 SMB ORIENT BC 20 9/22/1992 3/17/1971 $457,627 $384,792 CA BANK OF THE ORIENT , MILLBRAE BR MILLBRAE, CA 2961682 11/15/1999 11/15/1999 BANK OF THE ORIENT , OAKLAND BR OAKLAND, CA -

HISTORICAL EVALUATION Museum Place Mixed-Use Project 160 Park Avenue San José, Santa Clara County, California (APN #259-42-023)

HISTORICAL EVALUATION Museum Place Mixed-Use Project 160 Park Avenue San José, Santa Clara County, California (APN #259-42-023) Prepared for: David J. Powers & Associates, Inc. 1871 The Alameda Suite 200 San José, CA 95126 4.14.2016 ARCHIVES & ARCHITECTURE, LLC PO Box 1332 San José, CA 95109-1332 http://www.archivesandarchitecture.com Historical Evaluation Table of Contents Table of Contents Table of Contents ........................................................................................................................... 2 Introduction ..................................................................................................................................... 4 Project Description...................................................................................................................... 4 Purpose and Methodology of this Study ..................................................................................... 5 Previous Surveys and Historical Status ...................................................................................... 6 Location Map .............................................................................................................................. 7 Assessor’s Map .......................................................................................................................... 8 Summary of Findings .................................................................................................................. 8 Background and Historic Context .................................................................................................. -

Alameda Business Association

Festival, Parade and Celebrations Grants Grant Amount Alameda Business Association $ 15,285 Event: Rose, White & Blue 4th of July Parade Grant will support the Rose, White and Blue 4th of July Parade and Picnic on July 4, 2015. Over 100 groups participate in the parade that traverses the Historic Shasta/Hanchett and Rose Garden Neighborhoods and finishes on The Alameda, with a festival and picnic to follow. Almaden Valley Women's Club $ 12,904 Event: Almaden Valley Art and Wine Festival Grant will support the 39th annual Almaden Valley Art and Wine Festival on September 20, 2015 at Almaden Lake Park. The festival includes juried arts and crafts with over 90 artists, international food, local entertainment, and a children’s area of arts, crafts and sports activities. Asian Americans for Community Involvement, Inc. $ 3,778 Event: CAAMFest San Jose Grant will support CAAMFest San Jose during September 17 - 20, 2015 at Camera 3 Theater in San Jose. Asian Americans for Community Involvement (AACI) joins in efforts with Center for Asian American Media (CAAM) to present the four day Asian film festival that reflects the diverse population of Asian Americans in San Jose and Santa Clara County. Campus Community Association $ 16,475 Event: Bark in the Park Grant will support the 19th Bark in the Park event on September 19, 2015 at William Street Park in the Naglee Park Neighborhood in downtown San Jose. The family- oriented event centers around the family canine and offers an educational stage, activities areas, demonstrations, children’s activities, food, live entertainment and vendor booths. Chinese Performing Arts of America $ 12,904 Event: CPAA Spring Festival Grant will support the 8th annual Spring Festival Silicon Valley scheduled during February 26 – March 6, 2016. -

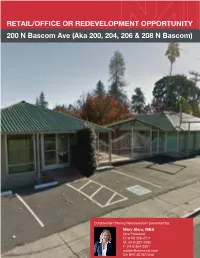

200 N Bascom

Retail/ Office Or Redevelopment Opportunity 200 N Bascom Ave, San Jose, CA 95128 telRETAIL/OFFICE+1 415 358 2111 OR REDEVELOPMENT OPPORTUNITY cell +1 415 297 5586 fax +1 415 354 3501 200 N Bascom Ave (Aka 200, 204, 206 & 208 N Bascom) Confidential Offering Memorandum presented by: Mary Alam, MBA Vice President O: (415) 358-2111 M: (415) 297-5586 F: (415) 354-3501 [email protected] CA BRE #01927340 Table of Contents 5 Section 1 Property Information 12 Section 2 Location Information 24 Section 3 Demographics Confidentiality & Disclosure Agreement The information contained in the following Investment Summary is proprietary and strictly confidential. It is intended to be reviewed only by the party receiving it from NAI Northern California Investment Real Estate Brokerage and should not be made available to any other person or entity without the written consent of Broker. This Investment Summary has been prepared to provide summary, unverified information to prospective purchasers, and to establish only a preliminary level of interest in the subject property. The information contained herein is not a substitute for a thorough due diligence investigation. Broker has not made any investigation, and makes no warranty or representation, with respect to the income or expenses for the subject property, the future projected financial performance of the property, the size and square footage of the property and improvements, the presence or absence of contaminating substances, PCB’s or asbestos, the compliance with State and Federal regulations, the physical condition of improvements thereon, or the financial condition or business prospects of any tenant, or any tenant’s plans or intentions to continue occupancy of the subject property. -

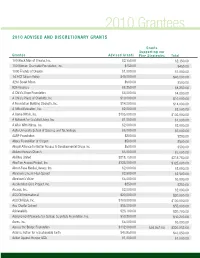

2010 Grantees 2010 Advised and Discretionary Grants

2010 Grantees 2010 Advised And discretionAry GrAnts Grants supporting our Grantee Advised Grants Five strategies total 100 Black Men of Omaha, Inc. $2,350.00 $2,350.00 100 Women Charitable Foundation, Inc. $450.00 $450.00 1000 Friends of Oregon $1,000.00 $1,000.00 1st ACT Silicon Valley $40,000.00 $40,000.00 42nd Street Moon $500.00 $500.00 826 Valencia $8,250.00 $8,250.00 A Child’s Hope Foundation $4,000.00 $4,000.00 A Child’s Place of Charlotte, Inc. $10,000.00 $10,000.00 A Foundation Building Strength, Inc. $14,000.00 $14,000.00 A Gifted Education, Inc. $2,000.00 $2,000.00 A Home Within, Inc. $105,000.00 $105,000.00 A Network for Grateful Living, Inc. $1,000.00 $1,000.00 A Wish With Wings, Inc. $2,000.00 $2,000.00 Aalto University School of Science and Technology $6,000.00 $6,000.00 AARP Foundation $200.00 $200.00 Abbey Foundation of Oregon $500.00 $500.00 Abigail Alliance for Better Access to Developmental Drugs Inc $500.00 $500.00 Abilene Korean Church $3,000.00 $3,000.00 Abilities United $218,750.00 $218,750.00 Abortion Access Project, Inc. $325,000.00 $325,000.00 About-Face Media Literacy, Inc. $2,000.00 $2,000.00 Abraham Lincoln High School $2,500.00 $2,500.00 Abraham’s Vision $5,000.00 $5,000.00 Accelerated Cure Project, Inc. $250.00 $250.00 Access, Inc. $2,000.00 $2,000.00 ACCION International $20,000.00 $20,000.00 ACCION USA, Inc. -

City of San Jose

Table of Contents Section 19 City of San Jose ....................................................................................................... 19-1 19.1 Introduction .............................................................................................................. 19-1 19.2 Internal Planning Process ......................................................................................... 19-7 19.3 Capability Assessment ........................................................................................... 19-15 19.3.1 Mitigation Progress .................................................................................... 19-15 19.3.2 Staff and Organizational Capabilities ........................................................ 19-18 19.3.3 National Flood Insurance Program ............................................................ 19-26 19.3.4 Resource List: ............................................................................................. 19-27 19.4 Vulnerability Assessment ...................................................................................... 19-27 19.4.1 Critical Facilities ........................................................................................ 19-27 19.4.2 Exposure Analysis ....................................................................................... 19-34 19.5 Mitigation Actions ................................................................................................. 19-71 19.5.1 Primary Concerns ......................................................................................