Historic Resource Project Assessment Cityview Plaza (A.K.A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Department/Proposal AIRPORT CAPITAL IMPVT

Special/Capital Fund Clean-Up Actions Annual Report 2010-2011 USE SO.URCE NET COST Personal Non-Personal/ Ending Fund Total Beg Fund Department/Proposal Services Equipment Other Balance Use Revenue Balance AIRPORT CAPITAL IMPVT FUND (520) ~irport Capital Program Fund Balance Reconciliation $65,492 $65,492 $65,492 $0 Rebudget: Taxiway W Improvements $35,000 ($35,000) $o Total AIRPORT CAPITAL IMPVT FUND (520) S0 $0 $35,000 $30,492 $65,492 $0 $65,492 $0 AIRPORT CUST FAC & TRANS FD (519) ~IRPORT Fund Balance Reconciliation - OPEB $301 $301 $301 $0 Fund Balance Reconciliation - Rate Stabilization Reserve $1,908,093 $1,908,093 $1,908,093 Total AIRPORT CUST FAC & TRANS FD (519) S0 $1,908,394 $0 $1,908,394 $0 $1,908,394 $0 AIRPORT FISCAL AGENT FUND (525) AIRPORT Fund Balance Reconciliation $2,658,037 $2,658,037 $2,658,037 $o Total AIRPORT FISCAL AGENT FUND (525) S0 $0 $2,658,037 $2,658,037 $0 $2,658,037 $0 AIRPORT MAINT & OPER FUND (523) CITY MANAGER Retirement Contributions Reconciliation ($316) $316 $o $o Unemployment Insurance Reconciliation ($395) $395 CITY ATTORNEY Retirement Contributions Reconciliation ($2,972) $2,972 $o $0 Unemployment Insurance Reconciliation ($3,711) $3,711 POLICE Retirement Contributions Reconciliation ($469) $469 $0 $0 Sp ecial/Capital Fund Clean-Up Actions Annual Report 2010-2011 USE SOURCE NET COST Personal Non-Personal! Ending Fund Total Beg Fund Department/Proposal Services Equipment Other Balance Use Revenue. Balance AIRPORT MAINT & OPER FUND (523) ~OLICE Unemployment Insurance Reconciliation ($589) $589 $o Retirement -

African American Community Service Agency Event

African American Community Service Agency Event: Juneteenth Grant will support the 39th Juneteenth Festival on June 20, 2020 at the Plaza de Cesar Chavez in downtown San Jose. Juneteenth recognizes the emancipation of slaves in the United States and is celebrated annually in more than 200 cities across the country. The event includes music, ethnic food, dance, and art for all ages. Aimusic School Event: Aimusic International Festival Grant will support the Aimusic International Festival: Intangible Chinese Heritage Celebration on April 25 through May 2, 2020 at San Jose Community College, California Theater, and San Jose State University. The festival promotes traditional Chinese music and performing arts. Almaden Valley Women's Club Event: Almaden Valley Art and Wine Festival Grant will support the 43rd annual Almaden Valley Art and Wine Festival on September 15, 2019 at Almaden Lake Park. The festival includes juried arts and crafts with over 90 artists, international food, local entertainment, and a children’s area of arts, crafts, and sports activities. Asian American Center of Santa Clara County (AASC) Event: Santa Clara County Fairgrounds TET Festival Grant request to support the 38th annual TET festival at the Santa Clara County Fairgrounds on January 25 and 26, 2020. The event celebrates the lunar new year, preserves, and promotes Vietnamese culture, raises funds for under-privileged youth and encourages youth leadership development and community involvement. Bay Area Cultural Connections (BayCC) Event: International Children’s Festival Grant will support the International Children’s Festival in April 2020 at Discovery Meadow Park in San Jose. The festival has been organized as a flagship event which brings families of different cultures together. -

HISTORICAL EVALUATION Museum Place Mixed-Use Project 160 Park Avenue San José, Santa Clara County, California (APN #259-42-023)

HISTORICAL EVALUATION Museum Place Mixed-Use Project 160 Park Avenue San José, Santa Clara County, California (APN #259-42-023) Prepared for: David J. Powers & Associates, Inc. 1871 The Alameda Suite 200 San José, CA 95126 4.14.2016 ARCHIVES & ARCHITECTURE, LLC PO Box 1332 San José, CA 95109-1332 http://www.archivesandarchitecture.com Historical Evaluation Table of Contents Table of Contents Table of Contents ........................................................................................................................... 2 Introduction ..................................................................................................................................... 4 Project Description...................................................................................................................... 4 Purpose and Methodology of this Study ..................................................................................... 5 Previous Surveys and Historical Status ...................................................................................... 6 Location Map .............................................................................................................................. 7 Assessor’s Map .......................................................................................................................... 8 Summary of Findings .................................................................................................................. 8 Background and Historic Context .................................................................................................. -

Alameda Business Association

Festival, Parade and Celebrations Grants Grant Amount Alameda Business Association $ 15,285 Event: Rose, White & Blue 4th of July Parade Grant will support the Rose, White and Blue 4th of July Parade and Picnic on July 4, 2015. Over 100 groups participate in the parade that traverses the Historic Shasta/Hanchett and Rose Garden Neighborhoods and finishes on The Alameda, with a festival and picnic to follow. Almaden Valley Women's Club $ 12,904 Event: Almaden Valley Art and Wine Festival Grant will support the 39th annual Almaden Valley Art and Wine Festival on September 20, 2015 at Almaden Lake Park. The festival includes juried arts and crafts with over 90 artists, international food, local entertainment, and a children’s area of arts, crafts and sports activities. Asian Americans for Community Involvement, Inc. $ 3,778 Event: CAAMFest San Jose Grant will support CAAMFest San Jose during September 17 - 20, 2015 at Camera 3 Theater in San Jose. Asian Americans for Community Involvement (AACI) joins in efforts with Center for Asian American Media (CAAM) to present the four day Asian film festival that reflects the diverse population of Asian Americans in San Jose and Santa Clara County. Campus Community Association $ 16,475 Event: Bark in the Park Grant will support the 19th Bark in the Park event on September 19, 2015 at William Street Park in the Naglee Park Neighborhood in downtown San Jose. The family- oriented event centers around the family canine and offers an educational stage, activities areas, demonstrations, children’s activities, food, live entertainment and vendor booths. Chinese Performing Arts of America $ 12,904 Event: CPAA Spring Festival Grant will support the 8th annual Spring Festival Silicon Valley scheduled during February 26 – March 6, 2016. -

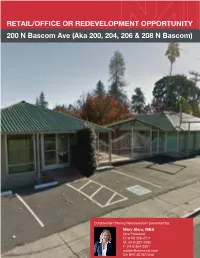

200 N Bascom

Retail/ Office Or Redevelopment Opportunity 200 N Bascom Ave, San Jose, CA 95128 telRETAIL/OFFICE+1 415 358 2111 OR REDEVELOPMENT OPPORTUNITY cell +1 415 297 5586 fax +1 415 354 3501 200 N Bascom Ave (Aka 200, 204, 206 & 208 N Bascom) Confidential Offering Memorandum presented by: Mary Alam, MBA Vice President O: (415) 358-2111 M: (415) 297-5586 F: (415) 354-3501 [email protected] CA BRE #01927340 Table of Contents 5 Section 1 Property Information 12 Section 2 Location Information 24 Section 3 Demographics Confidentiality & Disclosure Agreement The information contained in the following Investment Summary is proprietary and strictly confidential. It is intended to be reviewed only by the party receiving it from NAI Northern California Investment Real Estate Brokerage and should not be made available to any other person or entity without the written consent of Broker. This Investment Summary has been prepared to provide summary, unverified information to prospective purchasers, and to establish only a preliminary level of interest in the subject property. The information contained herein is not a substitute for a thorough due diligence investigation. Broker has not made any investigation, and makes no warranty or representation, with respect to the income or expenses for the subject property, the future projected financial performance of the property, the size and square footage of the property and improvements, the presence or absence of contaminating substances, PCB’s or asbestos, the compliance with State and Federal regulations, the physical condition of improvements thereon, or the financial condition or business prospects of any tenant, or any tenant’s plans or intentions to continue occupancy of the subject property. -

City of San Jose

Table of Contents Section 19 City of San Jose ....................................................................................................... 19-1 19.1 Introduction .............................................................................................................. 19-1 19.2 Internal Planning Process ......................................................................................... 19-7 19.3 Capability Assessment ........................................................................................... 19-15 19.3.1 Mitigation Progress .................................................................................... 19-15 19.3.2 Staff and Organizational Capabilities ........................................................ 19-18 19.3.3 National Flood Insurance Program ............................................................ 19-26 19.3.4 Resource List: ............................................................................................. 19-27 19.4 Vulnerability Assessment ...................................................................................... 19-27 19.4.1 Critical Facilities ........................................................................................ 19-27 19.4.2 Exposure Analysis ....................................................................................... 19-34 19.5 Mitigation Actions ................................................................................................. 19-71 19.5.1 Primary Concerns ...................................................................................... -

2021 Events Calendar

2021 Event Calendar City of San Jose Office of Cultural Affairs (Note: Listing on Calendar does not guarantee event approval) Contact: Contact: Est Daily Event Event Start Date Key Date Notes Event Name Status Account First Name Last Name Contact: Phone Contact: Email Location Attendance Coordinator Community Day: Lunar New Year 2021 Lion Dance 1/31/2021 10:00 AM 1/31: 10AM - 4:30PM Filming Complete San Jose Museum of Art RadHika Tandon 925-548-6887 [email protected] Circle of Palms 20 SG City of San Jose, Office of 2/1/2021 12:00 PM 2/1 - 7/31 Fountain Alley Construction Approved Cultural Affairs Nelly Torres 408-975-7134 [email protected] Fountain Alley 0 NT Stations of tHe Cross - Outdoor CHurcH Service 2021 4/2/2021 4:30 PM 4/2: 4:30PM-6:30PM (Info Only) Approved San Jose Way of tHe Cross 2021 Yunan Pei 510-246-9002 [email protected] Plaza de Cesar CHavez, St. James, City Hall 50 NT 5/1/2021 10:00 AM 5/1: 10:00 AM-1:00 PM Silicon Valley Take Steps 2021 (Info Only) Cancelled CroHn's & Colitis Foundation Nealika Caden 917-903-1404 [email protected] Green West 150 TT Every Friday 5/7/20 - 12/17/21 First Street between San Salvador St. & 5/7/2021 10:00 AM 10AM - 2PM Downtown Farmers Market 2021 Approved San Jose Downtown Association Donna ButcHer [email protected] William St. 1500 SG Willow Glen Elementary ScHool, Lincoln Avenue, MereditH Ave, Britton Ave, Coolidge Ave, Brace Ave, Newport Ave, Minnesota Ave, Iris Ct, Nevada Place, Nevada Ave, Glenwood Ave, Lupton Ave, CHerry Ave, Mildred Ave, -

Table of Contents

TABLE OF CONTENTS PICMET ’13 Japantown ................................................................. 20 Message from the President and CEO of PICMET .............2-3 Little Saigon .............................................................21 Executive Committee ........................................................4 West San José ........................................................... 21 Acknowledgments ............................................................. 5 Willow Glen ............................................................. 21 Advisory Council ..............................................................5 Los Gatos ..................................................................22 Panel of Reviewers ............................................................6 Campbell .................................................................. 22 Past LTM Award Recipients ............................................. 7 Rose Garden ............................................................. 22 Past Medal of Excellence Award Recipients ................... 8 San José Museum of Art ..........................................23 The Tech Museum of Innovation ............................23 PICMET ’13 AWARDS Arts, Entertainment & Events .........................................23 Student Paper Awards ................................................. 9-10 San José Convention & Visitors Bureau ..................23 LTM Awards ..................................................................... 11 Artsopolis ................................................................ -

TO: EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE FROM: Kerry Adams Hapner

EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE: 05-07-18 ITEM: V. B. 1 TO: EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE FROM: Kerry Adams Hapner SUBJECT: PROPOSED 2018-2019 FESTIVAL, DATE: May 3, 2018 PARADE & CELEBRATION GRANT AWARDS RECOMMENDATION Recommend that the Arts Commission recommend that the City Council approve the proposed FY 2018-2019 Festival, Parade and Celebration Grant awards specified in Attachment A and subject to the availability of funds appropriated in the City's FY 2018-2019 Operating Budget. BACKGROUND Through the Office of Cultural Affairs (OCA), the City of San Jose provides a limited number of Festival, Parade & Celebration Grant (FPC) awards each year in order to expand access for all City residents to a wide range of cultural experiences in the form of community festivals, parades and celebrations, large and small. These events are often held in public spaces and are always open to the entire public. Most FPC-supported events have free attendance, although a few have fee-based admission to some parts of or the entire event. In various ways, these festivals contribute to the City’s cultural enrichment and economic enhancement, and they help to promote the City to visitors. As noted in the guidelines, FPC funding is granted through a competitive process. Applications are weighed each year by a review panel for their responsiveness to the evaluation criteria published in the program information booklet. ANALYSIS The panel met on March 1 – 2, 2018 to complete its evaluation and was impressed by the overall quality and quantity of cultural offerings in San Jose. EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE May 3, 2018 Subject: Proposed 2018-2019 Festival, Parade & Celebration Grants Page 2 of 14 The FPC Grant Review Panel is comprised annually of individuals experienced in special event production, community members familiar with special events in San Jose and a member of the Arts Commission. -

Primary & Secondary Sources

Primary & Secondary Sources Brands & Products Agencies & Clients Media & Content Influencers & Licensees Organizations & Associations Government & Education Research & Data Multicultural Media Forecast 2019: Primary & Secondary Sources COPYRIGHT U.S. Multicultural Media Forecast 2019 Exclusive market research & strategic intelligence from PQ Media – Intelligent data for smarter business decisions In partnership with the Alliance for Inclusive and Multicultural Marketing at the Association of National Advertisers Co-authored at PQM by: Patrick Quinn – President & CEO Leo Kivijarv, PhD – EVP & Research Director Editorial Support at AIMM by: Bill Duggan – Group Executive Vice President, ANA Claudine Waite – Director, Content Marketing, Committees & Conferences, ANA Carlos Santiago – President & Chief Strategist, Santiago Solutions Group Except by express prior written permission from PQ Media LLC or the Association of National Advertisers, no part of this work may be copied or publicly distributed, displayed or disseminated by any means of publication or communication now known or developed hereafter, including in or by any: (i) directory or compilation or other printed publication; (ii) information storage or retrieval system; (iii) electronic device, including any analog or digital visual or audiovisual device or product. PQ Media and the Alliance for Inclusive and Multicultural Marketing at the Association of National Advertisers will protect and defend their copyright and all their other rights in this publication, including under the laws of copyright, misappropriation, trade secrets and unfair competition. All information and data contained in this report is obtained by PQ Media from sources that PQ Media believes to be accurate and reliable. However, errors and omissions in this report may result from human error and malfunctions in electronic conversion and transmission of textual and numeric data. -

9.28.15 Public Art Committee Meeting Materials

City of Florence Public Art Committee Florence City Hall 250 Hwy 101 Florence, OR 97439 541-997-3437 www.ci.florence.or.us September 14, 2015 10:00 a.m. AGENDA Members: Harlen Springer, Chairperson Susan Tive, Vice-Chairperson SK Lindsey, Member Jo Beaudreau, Member Ron Hildenbrand, Member Jennifer French, Member Jayne Smoley, Member Joshua Greene, Council Ex-Officio Member Kelli Weese, Staff Ex-Officio Member With 48 hour prior notice, an interpreter and/or TDY: 541-997-3437, can be provided for the hearing impaired. Meeting is wheelchair accessible. CALL TO ORDER – ROLL CALL 10:00 a.m. 1. APPROVAL OF AGENDA 2. PUBLIC COMMENTS This is an opportunity for members of the audience to bring to the Public Art Committee’s attention any item not otherwise listed on the Agenda. Comments will be limited to a maximum time of 15 minutes for all items. 3. NEW OR ONGOING PROJECTS • Discussion of interim policy to handle new or ongoing projects within long term Approx. work plan 10:05 a.m 4. SHORT REPORTS ON COMMUNITY PROJECTS Approx. • • Potential Totem Pole Art Piece Dancing with Sea Lions Project 10:15 a.m. • Downtown Revitalization Team • Florence Urban Renewal Agency 5. PUBLIC ART PLAN AND POLICY • Discussion of best ways to proceed with the following tasks, including assigning tasks to particular members and/or establishing sub-teams Example Art Plan & Policy Review: Discussion of important elements to o be incorporated into the City of Florence Public Art Plan & Policy Approx. 10:25 a.m. o Community Outreach: Discussion of potential community outreach practices to gather input including surveys and/or stakeholder meetings / interviews o Goals and Guiding Principles o Locations: Potential ideal locations for visual public art in the community 6. -

PROPOSED 2019-2020 FESTIVAL, DATE: May 6, 2019 PARADE & CELEBRATION GRANT AWARDS

EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE: 05-06-19 ITEM: TO: EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE FROM: Kerry Adams Hapner SUBJECT: PROPOSED 2019-2020 FESTIVAL, DATE: May 6, 2019 PARADE & CELEBRATION GRANT AWARDS RECOMMENDATION Recommend that the Arts Commission recommend that the City Council approve the proposed FY 2019-2020 Festival, Parade and Celebration Grant awards specified in Attachment A and subject to the availability of funds appropriated in the City's FY 2019-2020 Operating Budget. BACKGROUND Through the Office of Cultural Affairs (OCA), the City of San Jose provides a limited number of Festival, Parade & Celebration Grant (FPC) awards each year to expand access for all City residents to a wide range of cultural experiences in the form of community festivals, parades, and celebrations, large and small. These events are often held in public spaces and are always open to the entire public. Most FPC-supported events have free attendance, although a few have fee- based admission to some parts of or the entire event. In various ways, these festivals contribute to the City’s cultural enrichment and economic enhancement, and they help to promote the City to visitors. As noted in the guidelines, FPC funding is granted through a competitive process. Applications are weighed each year by a review panel for their responsiveness to the evaluation criteria published in the program information booklet. ANALYSIS The panel met on February 28 and March 1, 2019 to complete its evaluation and was impressed by the overall quality and quantity of cultural offerings in San Jose. EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE May 3, 2019 Subject: Proposed 2019-2020 Festival, Parade & Celebration Grants Page 2 of 16 The FPC Grant Review Panel is comprised annually of individuals experienced in special event production, community members familiar with special events in San Jose and a member of the Arts Commission.