Evaluation of Natural Capital to Support Land Use Planning

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fianarantsoa

NY FIA NGONA NA /SA N-KER/N TA ONA TAO FIANARANTSOA. NY KOMITIN, NY ISAN-KERINTAONA. N y M isio n ar y.— Kev. J. Pearse sy Rev. T. Rowlands sy Rev. A . S. Hnekett ary Rev. H . T. Johnson. N y Evangelistra.— Rafolo fFianarantsoaJ, Rainizana- mandroso f Ambalavao AtsimoJ, Andrianome f TsimaitohasoaJ, Rainijaonary fAlarobiaJ, Rainizanabelo fVohitsisahyJ, Rako- tovao f TsimahamenalamhaJ, Rainijoelina fAlahamisyJ, Ra- benjanahary f AmbohinamboarinaJ, Rakotovao f laritsenaJ. N y M pita n le in a n y Re n i- fiangon ana.— Ramorasata sy Rarinosy f A ntranobirikyJ, Rainiboreda sy Ravelojaonina flvohidahyJ, Andriamahefa sy Rabarijaonina f AmbalavaoJ, Rahaingomanana fFanjakana'j, Rainivao sy Rainimamonjy fAmbohinamboarinaJ, Rainisamoelina fAmbohimandroso A m - bonyj, Rajoelina sy Rasamoelina f Ambohimandroso AmbanyJ. N y I r a k y n y Re n i- eiangonana,— Andrianaivo sy Raben- godona f AntranobirihyJ, Rajaonimaria sy Razaka flvohidahyJ, Rainiketakandriana sy Rakotovao f AmbalavaoJ, Raiaiz&kftnosy sy Rainitsimba ary Rainizanajaza f Ambohimand,»eàQ T sermana a m y n y K om ity.— Raveloj aoniAa Sek r e ta r y.—Rakotovao. M p it a h ir y v o l a .— Rev. J. Pearse. M pa n d in ik a n y taratasim - bola.— Rafolo IRAKY NY ISAN-KERINTAONA NT AMPOVOA.N-TANT. Anarany. Tany ampianarany. Andria nainelona . Iavonomby, Halangina. Andriambao ........... Ambohibary, Isandra (avar.) Rapaoly ........... Vohimarina, Iarindrano (avar.) Andrianay ................ Nasandratrony, Isandra (atsiai.) Raobena | ........... Manandriana Mpanampy J Rainianjalahy......... Iarinomby, Ambohimandroso (atsin.) Andriamitsirimanga Iandraina, Ambohimandroso (andref.) NY ANY AMY NY BARA. Ramainba ................ Sahanambo Andriambelo ...... Vohibe NY ANY AMY NY TANALA. Andrianantsiony .. Vohitrosy Anjolobato Vohimanitra NY ANY AMY NY SAKALAVA. -

Ecosystem Profile Madagascar and Indian

ECOSYSTEM PROFILE MADAGASCAR AND INDIAN OCEAN ISLANDS FINAL VERSION DECEMBER 2014 This version of the Ecosystem Profile, based on the draft approved by the Donor Council of CEPF was finalized in December 2014 to include clearer maps and correct minor errors in Chapter 12 and Annexes Page i Prepared by: Conservation International - Madagascar Under the supervision of: Pierre Carret (CEPF) With technical support from: Moore Center for Science and Oceans - Conservation International Missouri Botanical Garden And support from the Regional Advisory Committee Léon Rajaobelina, Conservation International - Madagascar Richard Hughes, WWF – Western Indian Ocean Edmond Roger, Université d‘Antananarivo, Département de Biologie et Ecologie Végétales Christopher Holmes, WCS – Wildlife Conservation Society Steve Goodman, Vahatra Will Turner, Moore Center for Science and Oceans, Conservation International Ali Mohamed Soilihi, Point focal du FEM, Comores Xavier Luc Duval, Point focal du FEM, Maurice Maurice Loustau-Lalanne, Point focal du FEM, Seychelles Edmée Ralalaharisoa, Point focal du FEM, Madagascar Vikash Tatayah, Mauritian Wildlife Foundation Nirmal Jivan Shah, Nature Seychelles Andry Ralamboson Andriamanga, Alliance Voahary Gasy Idaroussi Hamadi, CNDD- Comores Luc Gigord - Conservatoire botanique du Mascarin, Réunion Claude-Anne Gauthier, Muséum National d‘Histoire Naturelle, Paris Jean-Paul Gaudechoux, Commission de l‘Océan Indien Drafted by the Ecosystem Profiling Team: Pierre Carret (CEPF) Harison Rabarison, Nirhy Rabibisoa, Setra Andriamanaitra, -

TDR Annexe7 Rapport Analyse 322 Communes OATF

ETAT DES LIEUX DES 319 COMMUNES POUR LE FINANCEMENT ADDITIONNEL DU PROJET CASEF Février 2019 TABLE DES MATIERES TABLE DES MATIERES .................................................................................................................... i LISTE DES ACRONYMES ................................................................................................................ iii Liste des tableaux ......................................................................................................................... v Listes des Cartes ........................................................................................................................... v Liste des figures ............................................................................................................................vi Liste des photos ...........................................................................................................................vi I INTRODUCTION ....................................................................................................................... 1 II METHODOLOGIES .................................................................................................................... 2 II.1 CHOIX DES 322 COMMUNES OBJETS D’ENQUETE ............................................................... 2 II.2 CHOIX DES CRITERES DE SELECTION DES COMMUNES ........................................................ 5 II.3 METHODOLOGIE DE COLLECTE DE DONNEES ET ACTIVITES ................................................. 6 -

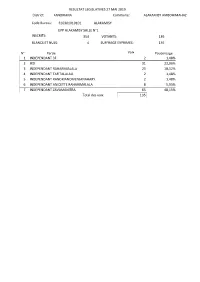

3103 Fandriana

RESULTAT LEGISLATIVES 27 MAI 2019 District: FANDRIANA Commune: ALAKAMISY AMBOHIMAHAZ Code Bureau: 310301010101 ALAKAMISY EPP ALAKAMISY SALLE N°1 INSCRITS: 354 VOTANTS: 139 BLANCS ET NULS: 4 SUFFRAGE EXPRIMES: 135 N° Partie Voix Poucentage 1 INDEPENDANT 3F 2 1,48% 2 IRD 31 22,96% 3 INDEPENDANT RAHARIMALALA 25 18,52% 4 INDEPENDANT TAFITALALAO 2 1,48% 5 INDEPENDANT RANDRIANOMENJANAHARY 2 1,48% 6 INDEPENDANT ANICETTE RAHARIMALALA 8 5,93% 7 INDEPENDANT ZAVAMANITRA 65 48,15% Total des voix 135 RESULTAT LEGISLATIVES 27 MAI 2019 District: FANDRIANA Commune: ALAKAMISY AMBOHIMAHAZ Code Bureau: 310301020101 AMBOHIMAHAZO EPP AMBOHIMAHAZO INSCRITS: 478 VOTANTS: 223 BLANCS ET NULS: 7 SUFFRAGE EXPRIMES: 216 N° Partie Voix Poucentage 1 INDEPENDANT 3F 2 0,93% 2 IRD 58 26,85% 3 INDEPENDANT RAHARIMALALA 74 34,26% 4 INDEPENDANT TAFITALALAO 18 8,33% 5 INDEPENDANT RANDRIANOMENJANAHARY 5 2,31% 6 INDEPENDANT ANICETTE RAHARIMALALA 7 3,24% 7 INDEPENDANT ZAVAMANITRA 52 24,07% Total des voix 216 RESULTAT LEGISLATIVES 27 MAI 2019 District: FANDRIANA Commune: ALAKAMISY AMBOHIMAHAZ Code Bureau: 310301030101 AMBONDRONA EPP AMBONDRONA SALLE N°01 INSCRITS: 426 VOTANTS: 184 BLANCS ET NULS: 5 SUFFRAGE EXPRIMES: 179 N° Partie Voix Poucentage 1 INDEPENDANT 3F 3 1,68% 2 IRD 39 21,79% 3 INDEPENDANT RAHARIMALALA 62 34,64% 4 INDEPENDANT TAFITALALAO 8 4,47% 5 INDEPENDANT RANDRIANOMENJANAHARY 8 4,47% 6 INDEPENDANT ANICETTE RAHARIMALALA 8 4,47% 7 INDEPENDANT ZAVAMANITRA 51 28,49% Total des voix 179 RESULTAT LEGISLATIVES 27 MAI 2019 District: FANDRIANA Commune: ALAKAMISY AMBOHIMAHAZ -

World Bank Document

Sample Procurement Plan Agriculture and Land Growth Management Project (P151469) Public Disclosure Authorized I. General 2. Bank’s approval Date of the procurement Plan: Original: January 2016 – Revision PP: December 2016 – February 2017 3. Date of General Procurement Notice: - 4. Period covered by this procurement plan: July 2016 to December 2017 II. Goods and Works and non-consulting services. 1. Prior Review Threshold: Procurement Decisions subject to Prior Review by the Bank as stated in Appendix 1 to the Guidelines for Procurement: [Thresholds for applicable Public Disclosure Authorized procurement methods (not limited to the list below) will be determined by the Procurement Specialist /Procurement Accredited Staff based on the assessment of the implementing agency’s capacity.] Type de contrats Montant contrat Méthode de passation de Contrat soumis à revue a en US$ (seuil) marchés priori de la banque 1. Travaux ≥ 5.000.000 AOI Tous les contrats < 5.000.000 AON Selon PPM < 500.000 Consultation des Selon PPM fournisseurs Public Disclosure Authorized Tout montant Entente directe Tous les contrats 2. Fournitures ≥ 500.000 AOI Tous les contrats < 500.000 AON Selon PPM < 200.000 Consultation des Selon PPM fournisseurs Tout montant Entente directe Tous les contrats Tout montant Marchés passes auprès Tous les contrats d’institutions de l’organisation des Nations Unies Public Disclosure Authorized 2. Prequalification. Bidders for _Not applicable_ shall be prequalified in accordance with the provisions of paragraphs 2.9 and 2.10 of the Guidelines. July 9, 2010 3. Proposed Procedures for CDD Components (as per paragraph. 3.17 of the Guidelines: - 4. Reference to (if any) Project Operational/Procurement Manual: Manuel de procedures (execution – procedures administratives et financières – procedures de passation de marches): décembre 2016 – émis par l’Unite de Gestion du projet Casef (Croissance Agricole et Sécurisation Foncière) 5. -

Small Hydro Resource Mapping in Madagascar

Public Disclosure Authorized Small Hydro Resource Mapping in Madagascar INCEPTION REPORT [ENGLISH VERSION] August 2014 Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized This report was prepared by SHER Ingénieurs-Conseils s.a. in association with Mhylab, under contract to The World Bank. It is one of several outputs from the small hydro Renewable Energy Resource Mapping and Geospatial Planning [Project ID: P145350]. This activity is funded and supported by the Energy Sector Management Assistance Program (ESMAP), a multi-donor trust fund administered by The World Bank, under a global initiative on Renewable Energy Resource Mapping. Further details on the initiative can be obtained from the ESMAP website. This document is an interim output from the above-mentioned project. Users are strongly advised to exercise caution when utilizing the information and data contained, as this has not been subject to full peer review. The final, validated, peer reviewed output from this project will be a Madagascar Small Hydro Atlas, which will be published once the project is completed. Copyright © 2014 International Bank for Reconstruction and Development / THE WORLD BANK Washington DC 20433 Telephone: +1-202-473-1000 Internet: www.worldbank.org This work is a product of the consultants listed, and not of World Bank staff. The findings, interpretations, and conclusions expressed in this work do not necessarily reflect the views of The World Bank, its Board of Executive Directors, or the governments they represent. The World Bank does not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this work and accept no responsibility for any consequence of their use. -

Ambositra Est La Suivante

UNIVERSITE D’ANTANANARIVO École Supérieure Polytechnique d’Antananarivo UFR Sciences Economiques et de Gestion de Bordeaux IV MEMOIRE DE DIPLOME D’ÉTUDES SUPÉRIEURES SPÉCIALISÉES OPTION : « ÉTUDES D’IMPACTS ENVIRONNEMENTAUX » En co-diplômation entre L’Université d’Antananarivo et l’Université Montesquieu-Bordeaux IV Intitulé : EETTUUDDEE DD’’’IIIMMPPAACCTTSS EENNVVIIIRROONNNNEEMMEENNTTAAUUXX EETT SSOOCCIIIAAUUXX DDUU PPRROOJJEETT «VVIIITTRRIIINNEE DDEE LL’’’EENNTTRREETTIIIEENN RROOUUTTIIIEERR NN°° 0022 »» SSUURR LL’’’AAXXEE :: AAmmbboossiiittrraa –– IIImmaaddyy IIImmeerriiinnaa –– MMaahhaazzooaarriiivvoo -- FFaannddrriiiaannaa Présenté le 09 octobre 2012 par Monsieur: RANDRIAMANANJO Dina Lalaina D E S S - E I E 2011 – 2012 D E S S EIE 2011 - 2012 École Supérieure Polytechnique d’Antananarivo UFR Sciences Economiques et de Gestion de Bordeaux IV MEMOIRE DE DIPLOME D’ÉTUDES SUPÉRIEURES SPÉCIALISÉES OPTION : « ÉTUDES D’IMPACTS ENVIRONNEMENTAUX » En co-diplômation entre L’Université d’Antananarivo et l’Université Montesquieu-Bordeaux IV Intitulé : EETTUUDDEE DD’’’IIIMMPPAACCTTSS EENNVVIIIRROONNNNEEMMEENNTTAAUUXX EETT SSOOCCIIIAAUUXX DDUU PPRROOJJEETT «VVIIITTRRIIINNEE DDEE LL’’’EENNTTRREETTIIIEENN RROOUUTTIIIEERR NN°° 0022 »» SSUURR LL’’’AAXXEE :: AAmmbboossiiittrraa –– IIImmaaddyy IIImmeerriiinnaa –– MMaahhaazzooaarriiivvoo -- FFaannddrriiiaannaa Présenté le 09 octobre 2012 par Monsieur : RANDRIAMANANJO Dina Lalaina Devant le jury composé de : Président : - Monsieur ANDRIANARY Philippe Antoine Professeur Titulaire Examinateurs : - Mme Sylvie -

En Suivant Ce Lien

Coopération décentralisée entre Suivi technique et financier des gestionnaires de réseau d’eau potable dans la Haute Matsiatra RAPPORT ANNUEL RESULTATS DE L’ANNEE 2018 Avec le soutien de TABLE DES MATIERES Table des matières .................................................................................................................................................. 2 Liste des figures ................................................................................................................................................... 5 Sigles et abréviations ........................................................................................................................................... 7 En résumé… 8 1. Éléments de cadrage ..................................................................................................................................... 9 1.1. Contexte général ..................................................................................................................................... 9 1.2. Les réseaux objet du STEFI 2018 ............................................................................................................. 9 2. La méthodologie de collecte de données ................................................................................................... 15 3. Présentation des acteurs et des adductions d’eau objet du STEFI 2018 .................................................... 16 3.1. Les communes concernées ................................................................................................................... -

3302 Ambohimahasoa

dfggfdgfdgsdfsdfdsfdsfsdfsdfdsfsdfdsfdmmm REPOBLIKAN'I MADAGASIKARA Fitiavana - Tanindrazana - Fandrosoana ----------------- HAUTE COUR CONSTITUTIONNELLE RESULTATS DEFINITIFS DU SECOND TOUR DE L'ELECTION PRESIDENTIELLE DU 19 DECEMBRE 2018 dfggfdgffhCode BV: 330201010101 dfggfdgffhBureau de vote: EPP AMBATOFOLAKA SALLE 1 dfggfdgffhCommune: AMBALAKINDRESY dfggfdgffhDistrict: AMBOHIMAHASOA dfggfdgffhRegion: HAUTE MATSIATRA dfggfdgffhProvince: FIANARANTSOA Inscrits : 291 Votants: 107 Blancs et Nuls: 8 Soit: 7,48% Suffrages exprimes: 99 Soit: 92,52% Taux de participation: 36,77% N° d'ordre Logo Photo Nom et Prenoms Candidat Voix obtenues Pourcentage 13 RAJOELINA Andry Nirina 85 85,86% 25 RAVALOMANANA Marc 14 14,14% Total voix: 99 100,00% Copyright @ HCC 2019 dfggfdgfdgsdfsdfdsfdsfsdfsdfdsfsdfdsfdmmm REPOBLIKAN'I MADAGASIKARA Fitiavana - Tanindrazana - Fandrosoana ----------------- HAUTE COUR CONSTITUTIONNELLE RESULTATS DEFINITIFS DU SECOND TOUR DE L'ELECTION PRESIDENTIELLE DU 19 DECEMBRE 2018 dfggfdgffhCode BV: 330201020101 dfggfdgffhBureau de vote: EPP AMBOHIMAHATSINJO SALLE 1 dfggfdgffhCommune: AMBALAKINDRESY dfggfdgffhDistrict: AMBOHIMAHASOA dfggfdgffhRegion: HAUTE MATSIATRA dfggfdgffhProvince: FIANARANTSOA Inscrits : 316 Votants: 124 Blancs et Nuls: 15 Soit: 12,10% Suffrages exprimes: 109 Soit: 87,90% Taux de participation: 39,24% N° d'ordre Logo Photo Nom et Prenoms Candidat Voix obtenues Pourcentage 13 RAJOELINA Andry Nirina 71 65,14% 25 RAVALOMANANA Marc 38 34,86% Total voix: 109 100,00% Copyright @ HCC 2019 dfggfdgfdgsdfsdfdsfdsfsdfsdfdsfsdfdsfdmmm -

Répartition De La Caisse-École 2020 Des Collèges D'enseignement

Repartition de la caisse-école 2020 des Collèges d'Enseignement Général DREN ALAOTRA-MANGORO CISCO AMBATONDRAZAKA Prestataire OTIV ALMA Commune Code Etablissement Montant AMBANDRIKA 503010005 CEG AMBANDRIKA 1 598 669 AMBATONDRAZAKA 503020018 C.E.G. ANOSINDRAFILO 1 427 133 AMBATONDRAZAKA 503020016 CEG RAZAKA 3 779 515 AMBATONDRAZAKA SUBURBAINE 503030002 C.E.G. ANDINGADINGANA 1 142 422 AMBATOSORATRA 503040001 CEG AMBATOSORATRA 1 372 802 AMBOHIBOROMANGA 503070012 CEG ANNEXE AMBOHIBOROMANGA 878 417 AMBOHIBOROMANGA 503150018 CEG ANNEXE MARIANINA 775 871 AMBOHIBOROMANGA 503150016 CEGFERAMANGA SUD 710 931 AMBOHIDAVA 503040017 CEG AMBOHIDAVA 1 203 171 AMBOHITSILAOZANA 503050001 CEG AMBOHITSILAOZANA 1 671 044 AMBOHITSILAOZANA CEG TANAMBAO JIAPASIKA 622 687 AMPARIHINTSOKATRA 503060013 CEG AMPARIHINTSOKATRA 1 080 499 AMPITATSIMO 503070001 CEG AMPITATSIMO 1 530 936 AMPITATSIMO 503070015 CEG ANNEXE AMBOHITANIBE 860 667 ANDILANATOBY 503080025 CEG ANDRANOKOBAKA 760 039 ANDILANATOBY 503080001 CEG ANDILANATOBY 1 196 620 ANDILANATOBY 503080026 CEG ANNEXE SAHANIDINGANA 709 718 ANDILANATOBY 503080027 CEG COMMUNAUTAIRE AMBODINONOKA 817 973 ANDILANATOBY 503080031 CEG COMMUNAUTAIRE MANGATANY 723 676 ANDILANATOBY 503080036 CEG COMMUNAUTAIRE RANOFOTSY 668 769 ANDROMBA 503090005 CEG ANDROMBA 1 008 043 ANTANANDAVA 503100020 CEG ANTANANDAVA 1 056 579 ANTSANGASANGA 503110004 CEG ANTSANGASANGA 757 763 BEJOFO 503120016 C.E.G. -

Sustainable Landscapes in Eastern Madagascar Environmental And

Sustainable Landscapes in Eastern Madagascar Environmental and Social Management Plan Translation of the original French version 19 May 2016 (Updated 23 August 2016) 1 Table of Contents Acronyms ............................................................................................................................................... 7 Glossary ................................................................................................................................................. 9 Executive Summary ............................................................................................................................ 10 1 Introduction ................................................................................................................................. 17 1.1 Background and Project Objectives ...................................................................................... 17 1.2 Objectives of the ESMP ........................................................................................................ 17 1.3 Link between the ESMP and the Environmental and Social Management Tools for the COFAV and CAZ Protected Areas ........................................................................................................ 18 2 Project Overview ......................................................................................................................... 20 2.1 Description of Components, Activities, and Relevant Sectors .............................................. 20 2.2 Targets and Characteristics -

Liste Des Communes Beneficiaires Au Financement Fdl-Papsp 2019

LISTE DES COMMUNES BENEFICIAIRES AU FINANCEMENT FDL-PAPSP 2019 N° Region District Nom commune Catégorie 1 ALAOTRA MANGORO MORAMANGA AMBOHIDRONONO CR 2 2 ALAOTRA MANGORO MORAMANGA AMPASIPOTSY MANDIALAZA CR 2 3 ALAOTRA MANGORO MORAMANGA ANALASOA ( TANANA AMBONY ) CR 2 4 ALAOTRA MANGORO MORAMANGA BEMBARY CR 2 5 ALAOTRA MANGORO MORAMANGA SABOTSY ANJIRO CR 2 6 AMORON'I MANIA AMBATOFINANDRAHANA AMBATOMIFANONGOA CR 2 7 AMORON'I MANIA AMBATOFINANDRAHANA FENOARIVO CR 2 8 AMORON'I MANIA AMBOSITRA AMBALAMANAKANA CR 2 9 AMORON'I MANIA AMBOSITRA AMBOSITRA CU 10 AMORON'I MANIA AMBOSITRA ANKAZOTSARARAVINA CR 2 11 ANALAMANGA AMBOHIDRATRIMO AMBATO CR 2 12 ANALAMANGA AMBOHIDRATRIMO AMBOHIPIHAONANA CR 2 13 ANALAMANGA AMBOHIDRATRIMO ANJANADORIA CR 2 14 ANALAMANGA AMBOHIDRATRIMO MAHABO CR 2 15 ANALAMANGA AMBOHIDRATRIMO MANJAKAVARADRANO CR 2 16 ANALAMANGA ANJOZOROBE ALAKAMISY CR 2 17 ANALAMANGA ANJOZOROBE AMPARATANJONA CR 2 18 ANALAMANGA ANJOZOROBE ANDRANOMISA AMBANY CR 2 19 ANALAMANGA ANJOZOROBE BERONONO CR 2 20 ANALAMANGA ANJOZOROBE TSARASAOTRA ANDONA CR 2 21 ANALAMANGA ATSIMONDRANO AMBATOFAHAVALO CR 2 22 ANALAMANGA ATSIMONDRANO ANDOHARANOFOTSY CR 2 23 ANALAMANGA ATSIMONDRANO BEMASOANDRO CR 2 24 ANALAMANGA AVARADRANO VILIAHAZO CR 2 25 ANALAMANGA MANJAKANDRIANA AMBATOMANGA CR 2 26 ANALAMANGA MANJAKANDRIANA MIADANANDRIANA CR 2 27 ANALANJIROFO FENERIVE EST AMBATOHARANANA CR 2 28 ANALANJIROFO FENERIVE EST AMBODIMANGA II CR 2 29 ANALANJIROFO FENERIVE EST AMPASINA MANINGORY CR 2 30 ANALANJIROFO FENERIVE EST ANTSIATSIAKA CR 2 31 ANALANJIROFO FENERIVE EST BETAMPONA