Stone Beads and Their Imitations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Lion-Faced Ḍākinī Sadhana སེང་གདོང་མའི

The Lion-Faced Ḍākinī Sadhana By Karma Chagme སེང་གདོང་མའི་སྒྲུབ་ཐབས་བཞུགས་སོ། ། ཆགས་མེད་ར་ག Translated and edited by Adele Tomlin The Lion-Faced Ḍākinī Sadhana Author: Karma Chagme Translator and Editor: Adele Tomlin Lion-Faced Ḍākinī EMPOWERMENT AND TRANSMISSION ARE ESSENTIAL BEFORE READING OR PRACTISING THIS TEXT First Edition, 2018. Publishing and Content Copyright: Adele Tomlin/Dakini Publications, 2018. Available for free private use and download. Please do not copy, re-produce or publish without express permission. 1 Translator’s Introduction The Lion-Faced Ḍākinī (seng ge gdong ma, Skt: Siṃhamukhā) is a female deity considered to be especially effective for dispelling black magic, curses, obstacles and harm-doers. In the Nyingma terma tradition, she is considered as one of the many forms of Padmasambhava, specifically a secret form of Guru Rinpoche manifested to avert spiritual obstacles and negativity. In the Sarma traditions she arises out of the Chakrasamvara cycle of tantras and belongs to the Highest Yoga Tantra 'wisdom' classification. The revelation of the root mantra for Lion-Faced Ḍākinī is also associated with the name of a famous translator and Sakya master, Bari Lotsawa (ba ri lo tsA) (aka Rinchen Drak (rin chen grags)) (1040-1111) — the second throne holder of Sakya school (Sakya Trizin). At the age of 63, he retained the seat of Sakya for a period of eight years (1102-1110). The great Sakya and Nyingma master, Jamyang Khyentse Wangpo wrote a history of the lineage of Siṃhamukhā, which has been translated and published in English onlinei. According to that biography, Bari was shown how to reveal the mantra treasure directly by Lion-Faced Ḍākinī herself, in order to avert the black magic and sorcery of an Indian master. -

BLAZE with MAJESTIC BRILLIANCE an Introduction to Himalayan Dzi Beads James Wainwright

THIS IS A FREE ARTICLE FROM SACRED HOOP MAGAZINE. Sacred Hoop is an independent magazine about Shamanism and Animistic Spirituality, based in West Wales, published four times a year since 1993. You may share this in any non-commercial way but reference to www.SacredHoop.org must be made if it is reprinted anywhere. To get a very special low-cost subscription to Sacred Hoop please visit : www.SacredHoop.org/offer.html ‘Within your own mind, you already have what you need to succeed, the ability to put others ahead of yourself. This is called virtue, the wish-fulfilling jewel’ Buddha Shakyamuni BLAZE WITH MAJESTIC BRILLIANCE An introduction to Himalayan dZi beads James Wainwright he people of Tibet and the There is one sacred bead those who wear them. As the Ancient Himalayan regions have long however, that stands out from all Tibetan Buddhist master, Sakyong Tadorned their bodies, temples, others. This is known as the dZi Mipham Rinpoche says: “A person banded agate, known as statues and ritual items with bead or dZi stone. with ziji has dignity, the radiant power Bhaisajyaguru dZi heirloom and prized beads. The most widely adopted of a mind that has relaxed into its Marco Polo, the famous spelling in the world today is dZi, own inherent strength”. medieval Italian explorer and however, it is also commonly trader, mentions how important spelled gzi or zi. The word dZi I first encountered dZi beads Mediterranean coral was to the translates as bright, shine or whilst I was an ordained Buddhist Tibetans, as far back as the luminous and should be pronounced monk, and became immediately Below: two-eyed dZi with red coral C13th. -

The Rehla of Ibn Battuta

Gackwad's Oriental Series Published under the Authority of the Maharaja Sayajirao University of Baroda, Baroda General Editor : A. N. Jani, M.A.. Ph.D.. D.Litt., KavyaHrtha. Director. Oriental Institute No. 122 THE REHLA OF IBN BATTUTA ( INDIA. MALDIVE ISLANDS AND CEYLON ) ) ) THE REHLA OF IBN BATTCTA • •••••• (INDIA, MALDIVE ISLANDS AND CEYLON TRANSLATION AND COMMENTARY By Mabdi Husain, M.A. ( Punjab ), Ph.D. (London), D.Liu. ( Sorbcnne, Paris Oriental Institute Baroda 1976 First Woo: 1953 Stednd Edition (Reprint): 1976 Copies 500 Published with Financial Aid of the University Grants Commission, Govt, of Gujarat & M. S. University of Baroda Price Rs. 71=00 Copies can be had from : — The Manager, UNIVERSITY PUBLICATION SALES UNIT, M. S. University of Baroda ( Sadhana Press ), Near Palace Gate, Palace Road, BARODA-390 001 Re-printed by photo-offset process at 'the " Printrasee-' Bagikhana, Baroda. for Shri Rasiklal G. Patel, Manager, Maharaja Sayajirao University of Baroda Press (Sadhana Press), Near Palace Gate, Palace Road, Baroda and published on behalf of the Maharaja Sayajirao University of Baroda by Pr. h- N. Jani, Director, Oriental Institute, Maharaja Sayajirao University of Baroda, Baroda, March 1976. FOREWORD The Rehla of Ibn Ea\\u\a was first published in the Gaekwad's Oriental Series as No. CXXII in 1953 by the then Director, the Late Professor G. H. Bhatt It should not be necessary to justify this reprint of an imported work of Muslim Cultural History, which has been in demand for a long time. I hope this reprint will fill a long-felt desideratum. T thanks the University Grants Commission, the Government of Gujarat and the M. -

Azuregreen Feb. 2012 Catalog

RETAIL 12A $ 3.00 SPRING EQUINOX 2012 16 BELL RD, PO BOX 48, MIDDLEFIELD, MA 01243-0048 PHONE: 413.623.2155 FAX: 413.623.2156 WWW.AZUREGREEN.NET AzureGreen Phone: 1.413.623.2155 Orders: 1.800.326.0804 Business Hours: AzureGreen is open Monday thru Friday between 9:30 am Fax: 1.866.663.2156 or 1.413.623.2156 and 6:00pm EST. E-Mail [email protected] Website: www.AzureGreen.net Payment Methods: AZUREGREEN MEMBERSHIP AzureGreen accepts Visa, MasterCard, Discover, Checks, and Money Orders, as well as PayPal payments. We will need your You can purchase an exclusive AzureGreen Membership which will last for 3 years! This membership will entitle you to a 15% discount on all of billing address, full name, and three digit CCV code (located your retail purchases (excluding discounted items). An excellent deal on the back of your card) in order to process your Credit Card. if you plan to buy over $175.00 in the next three years. $25.00 All Paypal payments should be made to [email protected]. Pay Pal can also process American Express, so through Pay Pal A Little About Who We Are: we can accept payment from that credit card as well. AzureGreen is the name that encompasses our relationship with the green growing earth and the azure waters and sky Backorders: that sustain it. AzureGreen is a gateway of Fairy magic. It is When an item you have ordered is not in stock here at AzureGreen a realm created by practical idealists to exemplify our our normal course of action is to leave the item on your order philosophies, and provide the reality check that improves if it is over $5.00 and ship it directly to you when it comes and refines them. -

The Complete Costume Dictionary

The Complete Costume Dictionary Elizabeth J. Lewandowski The Scarecrow Press, Inc. Lanham • Toronto • Plymouth, UK 2011 Published by Scarecrow Press, Inc. A wholly owned subsidiary of The Rowman & Littlefield Publishing Group, Inc. 4501 Forbes Boulevard, Suite 200, Lanham, Maryland 20706 http://www.scarecrowpress.com Estover Road, Plymouth PL6 7PY, United Kingdom Copyright © 2011 by Elizabeth J. Lewandowski Unless otherwise noted, all illustrations created by Elizabeth and Dan Lewandowski. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without written permission from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote passages in a review. British Library Cataloguing in Publication Information Available Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Lewandowski, Elizabeth J., 1960– The complete costume dictionary / Elizabeth J. Lewandowski ; illustrations by Dan Lewandowski. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references. ISBN 978-0-8108-4004-1 (cloth : alk. paper) — ISBN 978-0-8108-7785-6 (ebook) 1. Clothing and dress—Dictionaries. I. Title. GT507.L49 2011 391.003—dc22 2010051944 ϱ ™ The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences—Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992. Printed in the United States of America For Dan. Without him, I would be a lesser person. It is the fate of those who toil at the lower employments of life, to be rather driven by the fear of evil, than attracted by the prospect of good; to be exposed to censure, without hope of praise; to be disgraced by miscarriage or punished for neglect, where success would have been without applause and diligence without reward. -

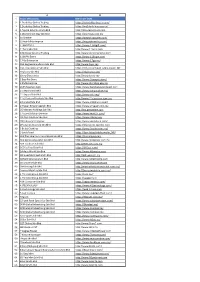

SOM Wallet List ADA 1Sept

A B 1 Boost Merchants Merchant's URL 2 1 Derfulday Online Trading https://1derfulday.boutir.com/ 3 1 Derfulday Online Trading https://my1derfulday.easy.co/ 4 1 Tour & Adventure Sdn Bhd http://1touradventure.com 5 1 World Short Stay Sdn Bhd https://shortstay.com.my 6 10 Sneaker https://wearshopoutlet.com/ 7 10Yearslife Enterprise https://mypawtnership.com/ 8 1168Gift PLT https://www.1168gift.com/ 9 11Tune Sdn Bhd http://www.11tune.com 10 1314 Love Surprise Trading http://www.welovesurprise.com 11 139BPM Event https://www.139bpm.com 12 17 Go Enterprise https://www.17go.my/ 13 180 Degrees Brandcom Sdn Bhd http://www.tapir.my 14 1957 De Centrum Sdn Bhd https://1957kopimakan.oddle.me/en_MY 15 1Balcony Sdn Bhd https://1balcony.com/ 16 1Now Electronics http://www.1now.my 17 2 Easy Pet Store https://www.2easypet.store/ 18 2 KM Enterprise http://www.2kmshop.easy.co 19 2055 Roastery Cafe https://www.bengbengsourdough.com 20 21 Beyond Sdn Bhd https://www.sunparadise.my/ 21 21 Beyond Sdn Bhd https://www.vito.my/ 22 21st Century Products Sdn Bhd http://www.21stcentury.com.my 23 22 United Sdn Bhd https://www.22delivery.com/ 24 24 Seven Enterprises Sdn Bhd https://www.24seven.com.my 25 25 Mascota Holdings Sdn Bhd http://my.perromart.com 26 27 Ecart Solution Services https://www.mart27.com/ 27 28 Days Solution Sdn Bhd https://www.28days.my 28 28 February Enterprise https://www.vgonature.com/ 29 2Footprint Dotcom Sdn Bhd https://2footprint.eprintit.com 30 3 Bulbs Clothing https://www.3bulbs.com.my/ 31 3 Souls Food https://3soulsfood.oddle.me/en_MY/ 32 -

ANGELO, Dante 2010 the Compulsive Construction of Heritage-Augmented.Pdf

THE COMPULSIVE CONSTRUCTION OF HERITAGE: MATERIAL CULTURE AND IDENTITY AT THE DAWN OF THE 21ST CENTURY IN NORTHWESTERN ARGENTINA A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE DEPARTMENT OF ANTHROPOLOGY AND THE COMMITTEE ON GRADUATE STUDIES OF STANFORD UNIVERSITY IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Dante A. Angelo July 2010 © 2010 by Dante Alejandro Angelo Zelada. All Rights Reserved. Re-distributed by Stanford University under license with the author. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution- Noncommercial 3.0 United States License. http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/us/ This dissertation is online at: http://purl.stanford.edu/bd264ms1829 ii I certify that I have read this dissertation and that, in my opinion, it is fully adequate in scope and quality as a dissertation for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Ian Hodder, Primary Adviser I certify that I have read this dissertation and that, in my opinion, it is fully adequate in scope and quality as a dissertation for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Lynn Meskell I certify that I have read this dissertation and that, in my opinion, it is fully adequate in scope and quality as a dissertation for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Michael Wilcox I certify that I have read this dissertation and that, in my opinion, it is fully adequate in scope and quality as a dissertation for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Rafael Curtoni Approved for the Stanford University Committee on Graduate Studies. Patricia J. Gumport, Vice Provost Graduate Education This signature page was generated electronically upon submission of this dissertation in electronic format. -

TMC Is Interim Operator

February 2008 The Manila Chronicle, home to the country’s best journalists “A classic case of the intersection of media power and political power in the Philippines” Catch the pre-launch special price Now available at the Lopez Memorial Museum Available online at www.benpres-holdings.com See story on page 9 First Gen gains SCTEX to open 100% ownership in Red Vulcan ... page 2 TMC is interim operator AFTER making its name from its suc- The interim contract is good for six P21 billion project to the joint venture cessful operations of the North Luzon months and can be renewed for anoth- of TMC, First Philippine Holdings Expressway (NLEX), Tollways Man- er six months. SCTEX concessionaire Corporations (FPHC), and Egis Road agement Corporation (TMC) is now Bases Conversion and Development Operation (ERO). TMC is primarily the new operator of the 94-km Subic- Authority (BCDA) awarded the opera- engaged with the operations and main- Clark-Tarlac Expressway (SCTEX). tion and maintenance (O&M) of this Turn to page 6 Witnesses expose tampered TV ratings ... page 3 2008 ayon kay OML Taon ng mga CFOs TINAGURIANG “taon ng mga CFOs Sa kanyang taunang pambungad o chief financial officers” ni Lopez na pananalita sa mga senior executives Group chairman Chairman Oscar M. ng Lopez Group of companies, sinabi ni Lopez (OML) ang taong 2008 dahil sa OML na umaasa siyang mareresolba na mga hamong takdang harapin ng mga ang mga isyu ukol sa debt restructuring finance executives ng grupo. sa madaling panahon. Check out Power Una sa listahan ng mga kailan- “During the past year (2007), An- gang gawin ngayong bagong taon ang gel Ong (pangulo ng Benpres) and his Plant Mall finds this pagtatapos ng financial restructuring ng staff have done a commendable job Valentine’s .. -

G a M E FO R Life

GAME FOR FOR GAME GAME FOR LiFE Lives Made Extraordinary Through Sport LiFE GAME FOR LIFE chronicles the journeys of 25 Singaporeans whose lives have been made extraordinary through sport. They are a diverse group of people: academics, business leaders, public servants and Lives Made Made Lives professional athletes who come from very different backgrounds. At fi rst glance, they appear to have little in common – except for their passion for sport and their emphatic belief that sport helped shape them into the resilient, self-actualised people they are today. With 25 stories of hope and achievement, GAME FOR LIFE will Lives Made inspire readers to discover their potential through sport. The book Extraordinary Extraordinary celebrates the effort and life lessons as much as it pays tribute to the Through Sport victories on the fi eld and in the arena. Through Sport Through Leadership/Sports/Biography 25 JOURNEYS Copyright © 2013 Singapore Sports Council, First Edition Published by: Singapore Sports Council 230 Stadium Boulevard Singapore 397799 www.ssc.gov.sg Produced by Write Editions® Write Editions® is a registered trademark and an imprint of JMatrix Consulting Private Limited, Singapore A Publishing & Communications Co. 14 Robinson Road #13-00 Far East Finance Building Singapore 048545 Email: [email protected] writeeditions.com | jmatrix.co All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in retrieval systems, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, scanning, or otherwise without the prior written permission of Singapore Sports Council. You shall notify Singapore Sports Council in writing of any unauthorised use of any of the copyright materials that come to your knowledge. -

Kurmanji Or Kurdish Language

Grammar of the Kurmanji or Kurdish Language E. B. Soane Author of ' To Kurdistan and Mesopotamia in Disguise , etc. LONDON LUZAC & CO. PUBLISHERS TO THE INDIA OFFICE 46 GREAT RUSSELL STREET INTRODUCTORY NOTICE IT is not so long ago that Kurdish was described by travellers as a harsh jargon, a very corrupt dialect of Persian, unintelligible to any but the folk who spoke it naturally; or again by others as an artificial language composed of Persian, Armenian, and Turltish ~zo~ds.It is neither of these. A little research proves it to be as worthy of the name of a separate and developed language as Turkish or Persian themselves. The early Medes and Persians spoke two different languages,Medic or Avestic and STEPHEN AUSTIN SONS, L1.1). Old Persian (that of the inscriptions), but the two tongues PI?INTEl?S,HERTFORD llave grown further apart than was originally the case; and while Persian has adopted almost as great a proportion of Arabic words as our own Anglo-Saxon did of Latin and Greek words to form modern English, Kurdish, eschewing importations, has kept parallel, but on different lines of grammar; and while frequently adopting a phrase or turn of expression from its sister language, has retained an independence of form and style that marks it as a tongue as different from the artificial Persian as the rough Kurd himself is from the polished Persian. The seclusion and exclusiveness which have been its preservation have also been the means of allowing a certain development into dialects in the almost inaccessible mountains which are the home of the Kurdish nation. -

A Comparative Study of the Social Function of African Algaita and Chinese Suona

A COMPARATIVE STUDY OF THE SOCIAL FUNCTION OF AFRICAN ALGAITA AND CHINESE SUONA A thesis submitted to the College of the Arts of Kent State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts By Shasha Zhu May, 2018 ii Thesis written by Shasha Zhu B. A., Tianjin Conservatory of Music, 2007 M. A., Tianjin Conservatory of Music, 2010 M. A., Kent State University, 2018 Approved by Kazadi wa Mukuna, Ph.D., Advisor, Master Thesis Committee Theodore Albrecht, Ph.D., Member, Master Thesis Committee Richard Devore, Ph.D., Member, Master Thesis Committee iii TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS ....................................................................................................................... iii LIST OF FIGURES ............................................................................................................................... iv LIST OF TABLES .................................................................................................................................. v ACKONWLEDGEMENTS ................................................................................................................... vi CHAPTER I. INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................ 1 II. THE GENESIS OF DOUBLE-REED MUSICAL INSTRUMENTS ........................... 19 III. THE ETYMOLOGY OF “ALGAITA” AND “SUONA” ........................................... 40 IV. THE MORPHOLOGICAL STRUCTURES OF THE AFRICAN ALGAITA AND THE CHINESE -

Acacia Wood Kangling

Ritual Arts for the Modern ChÖpa January, 2011 Lama Jinpa 1 School of Tibetan Healing Chö www.tibetancho.com MaChik Chöling Centers for Tibetan Healing Chöd 8 SANG NGAK CHÖKOR LING Sacred Mantra Path in Daily Life CHÖ Publishing 2011 2 contents ∂ A SACRED RITUAL INSTRUMENTS 1 Damaru .................................................................... 7 1b Damaru Case [Shup] ............................................. 12 2 Damaru Pendants—Chöpen ............................... 13 2b Chöpen Ornaments: Melong ............................. 14 3 Shing Kanglings ..................................................... 15 3b Shing Cases [Shup] ................................................ 18 4 Bells-Dorje .............................................................. 19 B SACRED DRESS 5 Domra (Chöd Hat) ................................................ 21 6 Rigdzin Shamo (Chöd Hat) ................................. 23 7 Tiger Seat Rug ........................................................ 25 Price List ..................................................................28 Contact & Ordering ..............................................29 Chöd Pray Flags—Cut Outs! ...............................31 3 Our VIsion ^ The mission and vision of DamaruWorks is 5-fold: 1. To perpetuate and preserve the traditions of Vajrayana though the accu- space rate creation and dispersal of ancient Tibetan ritual crafts with absolute integrity. 2. To provide the highest quality traditional practice materials to serious Vajrayana practitioners, especially Chöpas,