Diplomova Prace

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Omphalos Xv ·Núm

OCT. ejemplar gratuito año del Culturales Actividades 2018 14 p. Omphalos xv ·núm. I N TEATRO DE LAS ARTES. CENART BA Viernes 19, 20:00 h · Sábado 20 y domingo 21, 13:00 y 18:00 h 9 PALACIO DE BELLAS ARTES ESTAMOS RECUPERANDO JUNTOS NUESTRO PATRIMONIO CULTURAL Templo de Santa Prisca, Taxco, Guerrero A UN AÑO, La Secretaría de Cultura trabaja, día SE HAN RECUPERADO EN SU TOTALIDAD: a día, en recuperar 2,340 inmuebles que fueron afectados en 11 estados del país, joyas emblemáticas que han sido testigo 450 del acontecer nacional. inmuebles históricos México enfrenta uno de los mayores retos de su historia:restaurar los 41 bienes históricos y artísticos zonas dañados por los sismos de septiembre arqueológicas de 2017. Rendición de cuentas a la ciudadanía La Secretaría de Cultura reconoce la labor de las comunidades, los especialistas del INAH, OCTUBRE 2018 INBA, la Dirección General de Sitios y Monumentos del Patrimonio Cultural, y el apoyo de la B UNAM, el Fideicomiso Fuerza México, los gobiernos estatales e instancias internacionales. OCTUBRE · 2018 SECRETARÍA DE CULTURA María Cristina García Cepeda secretaria Índice Saúl Juárez Vega ESTAMOS RECUPERANDO JUNTOS subsecretario de desarrollo cultural Jorge Gutiérrez Vázquez NUESTRO PATRIMONIO CULTURAL subsecretario de diversidad cultural y fomento a la lectura Francisco Cornejo Rodríguez oficial mayor Miguel Ángel Pineda Baltazar director general de comunicación Social INSTITUTO NACIONAL DE BELLAS ARTES Lidia Camacho Camacho directora general 2 PALACIO DE BELLAS ARTES Roberto Vázquez Díaz PBA -

Presentación De Powerpoint

INFORME CORRESPONDIENTE AL 2017 INFORME CORRESPONDIENTE AL 2017. Informe presentado por el Consejo Directivo Nacional de la Sociedad Mexicana de Autores de las Artes Plásticas, Sociedad De Gestión Colectiva De Interés Público, correspondiente al año 2017 ante la Asamblea General de Socios. Agradezco a todos los asistentes de su presencia en la actual asamblea informativa, dando a conocer todos los por menores realizados en el presente año, los cuales he de empezar a continuación: 1.- Se asistió a la reunión general de la Cisac, tratándose temas diversos según el orden del día presentado, plantando sobre el acercamiento con autores de los países: Guatemala, Panamá y Colombia para la conformación de Sociedades de Gestión en dichas naciones, donde estamos apoyando para su conformaciones y así tener mayor representatividad de nuestros socios, además de la recaudación de regalías. Les menciono que en primera instancia se desea abrir con el gremio de la música, pero una vez instaurada la infraestructura se piensa trabajar a otros gremios como la nuestra. Actualmente estamos en platicas de representación de nuestro repertorio en las sociedades de gestión ya instaladas en Costa Rica y Republica Dominicana donde existen pero para el gremio musical, considerando utilizar su plataforma e infraestructura para el cobro regalías en el aspecto de artes visuales en dichos países, tal como se piensa realizar en las naciones antes mencionadas una vez creadas. Dentro de la asamblea general anual de la CISAC, llevada a cabo en New York, logramos cerrar la firma de un convenio con la Sociedad de Autores y Artistas Visuales y de Imágenes de Creadores Franceses, con residencia en París, con ello cumpliendo con la meta de tener más ámbito de representación de los derechos autorales de nuestros socios nacionales. -

80 Aniversario Del Palacio De Bellas Artes

INSTITUTO NACIONAL DE BELLAS ARTES Dirección de Difusión y Relaciones Públicas Subdirección de Prensa "2015, Año del Generalísimo José María Morelos y Pavón" México, D. F., a 19 de noviembre de 2015 Boletín Núm. 1570 Celebrará el Salón de la Plástica Mexicana su 66º aniversario con una serie de exposiciones, dentro y fuera de los muros del recinto La muestra principal será inaugurada el jueves 19 de noviembre a las 19:30 Recibirán reconocimientos Arturo García Bustos, Rina Lazo, Arturo Estrada, Guillermo Ceniceros, Luis Y. Aragón y Adolfo Mexiac el 8 de diciembre A lo largo de más de seis décadas de existencia, el Salón de la Plástica Mexicana (SPM) se ha caracterizado por ser extensivo e incluyente, y en el que todas las corrientes del arte mexicano y las generaciones de artistas tienen cabida. Así lo asevera Cecilia Santacruz Langagne, coordinadora general del organismo dependiente del Instituto Nacional de Bellas Artes (INBA), al informar que se celebrará su 66º aniversario con diversas actividades. Aun cuando el SPM ya no continúa con su vocación inicial –ser una galería de venta libre para la promoción de sus integrantes–, en ningún momento ha dejado de ser un referente para el arte mexicano, refiere Santacruz. Desde su fundación en 1949, el SPM ha incluido la obra más representativa de la plástica nacional. A pesar de las múltiples vicisitudes por las que ha atravesado, han formado parte de él cientos de pintores, escultores, grabadores, dibujantes, ceramistas y fotógrafos de todas las tendencias y generaciones. Paseo de la Reforma y Campo Marte S/N, Módulo A, 1er. -

El Museo Mural Diego Rivera Realiza Recorrido En Lengua Náhuatl, En El Contexto Del Día Internacional De Los Museos

Dirección de Difusión y Relaciones Públicas Ciudad de México, a 19 de mayo de 2019 Boletín núm. 713 El Museo Mural Diego Rivera realiza recorrido en lengua náhuatl, en el contexto del Día Internacional de los Museos Este proyecto de inclusión y acceso al arte fortalece el papel de los museos como espacios de encuentro Se trata de un acercamiento a la diversidad cultural del país y a la obra del artista El Museo Mural Diego Rivera celebró con un recorrido guiado en lengua náhuatl en torno al mural Sueño de una tarde dominical en la Alameda Central, que el artista guanajuatense pintara entre julio y septiembre de 1947. El recorrido, además de abordar el contenido de la obra, también alude la historia del recinto. Esta actividad del Instituto Nacional de Bellas Artes y Literatura (INBAL), realizada en el marco del Día Internacional de los Museos, se llevó a cabo en colaboración con el Instituto Nacional de Lenguas Indígenas (INALI). “El proyecto abordó los temas que ofrecemos durante nuestras visitas tradicionales, sólo que en náhuatl. Se habló sobre la historia del mural y de los personajes que aparecen, que fueron protagonistas de la historia de nuestro país. Este es un recorrido no sólo de acercamiento a la obra de Rivera, sino, particularmente, a la diversidad cultural que existe en el país”, señaló en entrevista Marisol Argüelles, directora del recinto. “El mural concentra varias etapas de la historia de México. Se explica el momento histórico, quiénes son los personajes, el papel de éstos dentro de la historia y de la composición pictórica y se alude a algunas reflexiones que el artista hace a través de su obra. -

Hubo 16 Lesionados En Cinco Accidentes

è Nacionales 8A è Internacional 10A è Deportes C Lunes 9 de Abril de 2007 Año 54, Número 17,872 Colima, Col. $5.00 Tres Muertos y un Desaparecido en Semana Santa Hubo 16 Lesionados Se Rebasaron Expectativas en Cinco Accidentes lSectur: La derrama económica fue de 127 millones 398 mil 286 pesos lDos de los tres fallecidos, por lLa afluencia, de más de cien mil ahogamiento en agua salada; el turistas lLos hoteles, al cien por otro, un bebé de nueve meses en ciento en los días santos accidente carretero lEn Cuyutlán se ofrecieron eventos no aptos para Jesús TREJO MONTELON menores lLa PFP se negó a dar El período vacacional correspondiente información sobre los resultados a la Semana Mayor, mismo que concluyó ayer del operativo de seguridad domingo, arrojó como resultado una afluencia turística de más de cien mil personas en todo Sergio URIBE ALVARADO el estado; ocupación hotelera al cien por ciento en los días santos, y una derrama Tres personas perdieron la vida, económica de 127 millones 398 mil 286 pesos, mientras otra se encuentra en calidad de informó el secretario de Turismo, Sergio desaparecida, ello en diferentes hechos Marcelino Bravo Sandoval. ocurridos durante el período vacacional Mediante un comunicado emitido por de Semana Santa, así lo dio a conocer la la Sectur, se informa que en lo que respecta a Procuraduría General de Justicia del la afluencia turística en el estado, se reportaron Estado (Pgje). 96 mil 965 visitantes con cuarto pagado, sin De acuerdo al reporte de la contar a las personas que se hospedan en dependencia policiaca, primeramente el villas, con familiares o en casas de campaña, pasado martes 3 de abril, un hombre y la derrama económica alcanzó los 127 desapareció en la playa Olas Altas, frente millones 398 mil 286 pesos, beneficiando a al hotel Pacífico, en Manzanillo. -

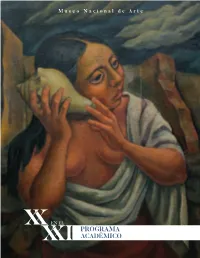

PROGRAMA ACADÉMICO Imagen De Portada

Museo Nacional de Arte PROGRAMA ACADÉMICO Imagen de portada: Gabriel Fernández Ledesma (1900-1983) El mar 1936 Óleo sobre tela INBAL / Museo Nacional de Arte Acervo constitutivo, 1982 PROGRAMA ACADÉMICO Diego Rivera, Roberto Montenegro, Gerardo Murillo, Dr. Atl, Joaquín Clausell, David Alfaro Siqueiros, Lola Cueto, María Izquierdo, Adolfo Best Maugard, Pablo O’Higgins, Francisco Goitia, Jorge González Camarena, Rufino Tamayo, Abraham Ángel, entre muchos otros, serán los portavoces de los grandes cometidos de la plástica nacional: desde los pinceles transgresores de la Revolución Mexicana hasta los neomexicanismos; de las Escuelas al Aire Libre a las normas metódicas de Best Maugard; del dandismo al escenario metafísico; del portentoso género del paisaje al universo del retrato. Una reflexión constante que lleva, sin miramientos, del XX al XXI. Lugar: Museo Nacional de Arte Auditorio Adolfo Best Maugard Horario: Todos los martes de octubre y noviembre De 16:00 a 18:00 h Entrada libre XX en el XXI OCTUBRE 1 de octubre Conversatorio XX en el XXI Ponentes: Estela Duarte, Abraham Villavicencio y David Caliz, curadores de la muestra. Se abordarán los grandes ejes temáticos que definieron la investigación, curaduría y selección de obras para las salas permanentes dedicadas al arte moderno nacional. 8 de octubre Decadentismo al Modernismo nacionalista. Los modos de sentir del realismo social entre los siglos XIX y XX Ponente: Víctor Rodríguez, curador de arte del siglo XIX del MUNAL La ponencia abordará la estética finisecular del XIX, con los puentes artísticos entre Europa y México, que anunciaron la vanguardia en la plástica nacional. 15 de octubre La construcción estética moderna. -

Dear All, Thank You So Much for Taking the Time to Read This Early Draft Of

Dear all, Thank you so much for taking the time to read this early draft of what I hope to turn into the fifth chapter of my dissertation. My dissertation analyzes the ways in which the political role of artists and cultural institutions in Mexico have changed in the wake of a series of political and socio-economic transformations commonly referred to as the country’s “twin” neoliberal and democratic transition. This chapter is a direct continuation of the previous one, in which I analyze the way the state directly commissioned and deployed art during the official bicentennial commemorations of Independence and the centennial commemorations of Revolution in 2010. In this chapter, my goal is to contrast these official commemorations with the way members of the artistic community itself engaged critically in the commemorative events and, by extension, with the state. I am testing many of the arguments here, as well as the structure of the chapter, and I am looking forward to any suggestions, including the use of theory to sustain my arguments. To situate this chapter, I am pasting below a one-paragraph contextual introduction from the previous chapter: 2010 was one of the most violent years in Mexico’s recent history. The drug war launched by president Felipe Calderón a few years earlier was linked to over fifteen thousand homicides, and the visual and media landscape was saturated with gruesome images of the drug war’s casualties. That same year, Mexico commemorated two hundred years of independence and one hundred years of revolution. But despite the spectacular (and expensive) attempts to make the state’s power highly visible, the celebrations were marked by public indifference, resistance, and even outright hostility, and fell far from being an innocent expression of collective festivity. -

La Voz De Esperanza

I must confess that I’m not great at math (though, I thought I was). I thought we were celebrating 20 years of Calaveras in La Voz this year! The frst issue of Calaveras appeared in November, 1999. The Math La Voz de says it’s been twenty years (2019-1999 = 20)—but my fngers say twenty-one! If you count the frst Esperanza issue starting in 1999 and continue on your fngers November, 2019 to 2019, it’s 21 years of Calaveras! So we missed the Vol. 32 Issue 9 20th! Still, we must celebrate! And we are—starting Editor: Gloria A. Ramírez with the cover of this issue. Design: Elizandro Carrington Cover Art: Dream of a Sunday Afternoon in Diego Rivera’s, Dream of a Sunday Afternoon in Alameda Central Park (Sueño de Alameda Central Park /Sueño de una tarde una tarde dominical en la Alameda Central) painted circa 1947 is a massive mural, dominical en la Alameda Central by Diego Rivera 4.8 x 15 meters, located at the Museo Mural Diego Rivera in Mexico City, next to Contributors the Alameda Park in my favorite part of Mexico City, Centro Historico, the historic Gloria Almaraz, Ellen Riojas Clark, Victor M. center of Mexico. The mural depicts famous people and events in Mexico’s history Cortez, Moisés Espino del Castillo, Anel Flores, Ashley G., Rachel Jennings, Pablo Martinez, from conquest to colonization and the Mexican Revolution happening all at once—as Dennis Medina, Adriana Netro, Kamala Platt, hundreds of famous personalities stroll through or spend time at the Alameda Central Rosemary Reyna-Sánchez, Carla Rivera, Norma Park that was created in 1592. -

Angelina Beloff Como Misionera Cultural: Una Revalorización De Su Arte»

GUERRERO OLAVARRIETA, Ana Paula (2017). «Angelina Beloff como misionera cultural: una revalorización de su arte». Monograma. Revista Iberoamericana de Cultura y Pensamiento, n. 1, pp. 177-193. URL: http://revistamonograma.com/index.php/mngrm/article/view/12 FECHA DE RECEPCIÓN: 17/10/2017 · FECHA DE ACEPTACIÓN: 7/11/2017 ISSN: 2603-5839 Angelina Beloff como misionera cultural: una revalorización de su arte Ana Paula GUERRERO OLAVARRIETA Universidad Iberoamericana, Ciudad de México [email protected] Resumen: ¿Por qué estudiar a Angelina Beloff? ¿Qué relación tiene con el contexto mexicano? Los estudios que hay acerca de Angelina Beloff se han centrado bajo la sombra de Diego Rivera, con quien tuvo una relación de diez años. Por consiguiente, la investigación está encaminada a tener un acercamiento más crítico a su obra y a su desempeño laboral en Europa y en México del siglo XX. La presente investigación busca rescatar a Beloff dentro del contexto de los artistas mexicanos de la época. Sin hacer un recuento biográfico, toma como referencia diversos textos que la mencionan, para sustentar y debatir junto con los que han excluido la figura de Beloff dentro de la historiografía mexicana. Asimismo explica por qué es relevante estudiar a esta artista extranjera que decidió vivir en nuestro país junto con otras figuras del medio artístico contemporáneo. Palabras clave: Angelina Beloff, extranjera, arte mexicano, exclusión, historiografía. Abstract: Why study Angelina Beloff? What relationship does she has with the Mexican context? Studies about Angelina Beloff have been centered under Diego Rivera's shadow, with whom she had a relationship for ten years. Therefore, the investigation is driven to have a more critical close up to her art work and her job performance in Europe and Mexico during the Twentieth Century. -

INFORME ANUAL CORRESPONDIENTE AL ÚLTIMO SEMESTRE DEL 2013 Y PRIMER SEMESTRE DE 2014

INFORME ANUAL CORRESPONDIENTE AL ÚLTIMO SEMESTRE DEL 2013 y PRIMER SEMESTRE DE 2014. Informe presentado por el Consejo Directivo Nacional de la Sociedad Mexicana de Autores de las Artes Plásticas, Sociedad De Gestión Colectiva De Interés Público, correspondiente al segundo semestre del 2013 y lo correspondiente al año 2014 ante la Asamblea General de Socios. Nuestra Sociedad de Gestión ha tenido varios resultados importantes y destacables con ello hemos demostrado que a pesar de las problemáticas presentadas en nuestro país se puede tener una Sociedad de Gestión como la nuestra. Sociedades homologas como Arte Gestión de Ecuador quienes han recurrido al cierre de la misma por situaciones económicas habla de la crisis vivida en nuestros días en Latinoamérica. Casos como Guatemala, Colombia, Honduras en especial Centro América, son a lo referido, donde les son imposibles abrir una representación como Somaap para representar a sus autores plásticos, ante esto damos las gracias a todos quienes han hecho posible la creación y existencia de nuestra Sociedad Autoral y a quienes la han presidido en el pasado enriqueciéndola y dándoles el impulso para que siga existiendo. Es destacable mencionar los logros obtenidos en las diferentes administraciones donde cada una han tenido sus dificultades y sus aciertos, algunas más o menos que otras pero a todas les debemos la razón de que estemos en estos momentos y sobre una estructura solida para afrontar los embates, dando como resultado la seguridad de la permanencia por algunos años más de nuestra querida Somaap. Por ello, es importante seguir trabajando en conjunto para lograr la consolidación de la misma y poder pensar en la Somaap por muchas décadas en nuestro país, como lo ha sido en otras Sociedades de Gestión. -

La Secretaría De Cultura Da Conocer Nombramientos En Museos Del INBAL

Comunicado No. 79 Ciudad de México, viernes 15 de febrero de 2019 La Secretaría de Cultura da conocer nombramientos en compañías y museos del INBAL Las compañías artísticas promoverán nuevos esquemas de producción artística, una perspectiva nacional, enfoques de inclusión social, igualdad e interdisciplina Se creará la Red Nacional de Museos para fortalecer su gestión y mejores prácticas de servicio La Directora General del Instituto Nacional de Bellas Artes y Literatura (INBAL), doctora Lucina Jiménez, por acuerdo con la Secretaria de Cultura, licenciada Alejandra Frausto, en cumplimiento con la normatividad vigente, y luego de diversos diálogos con comunidades artísticas, da a conocer nuevos nombramientos y confirmaciones de las personas que tendrán la responsabilidad de fortalecer la promoción nacional e internacional de las compañías artísticas, así como la vocación de los 18 espacios museísticos que dependen del INBAL, con especial énfasis en la recuperación del diálogo entre el arte moderno y el arte contemporáneo mexicano, el manejo de sus colecciones, así como las itinerancias nacionales e internacionales. Compañías Artísticas Las compañías artísticas del Instituto han iniciado la redefinición de los modelos de producción artísticas de sus respectivas disciplinas que tomarán en cuenta la itinerancia nacional, la coproducción nacional e internacional, la interdisciplina, así como enfoques de promoción de la igualdad y la inclusión social. En la Compañía Nacional de Danza se crea una Codirección, la cual tendrán a su cargo la -

Museos Del INBAL Presentan Exposiciones Nacionales E Internacionales En El 2020

Dirección de Difusión y Relaciones Públicas Ciudad de México, a 17 de enero de 2020 Boletín núm. 049 Museos del INBAL presentan exposiciones nacionales e internacionales en el 2020 ● Destacan París de Modigliani y sus contemporáneos en el Museo del Palacio de Bellas Artes, Picasso y el exilio. Una historia del arte español en resistencia en el Museo de Arte Moderno y Luchita Hurtado. I Live I Die I Will Be Reborn en el Museo Tamayo ● Se realizarán importantes revisiones a la obra de Lola Álvarez Bravo, Nunik Sauret, Leopoldo Méndez, Juan José Gurrola, Aube Bretón, Alexandre Estela, Daniel García Andújar, Bill Viola, entre otros El programa de exposiciones de los museos del Instituto Nacional de Bellas Artes y Literatura (INBAL) ofrecerá al público este año un amplio panorama tanto de expresiones de arte contemporáneo, como grandes retrospectivas de artistas nacionales e internacionales, así como muestras temáticas que revisan las colecciones nacionales que resguarda el Instituto, fortaleciendo así la vocación de sus recintos y promoviendo la colaboración interinstitucional. El Museo del Palacio de Bellas Artes (MPBA) inicia su programación con la exposición París de Modigliani y sus contemporáneos, la cual se enmarca en la conmemoración del centenario del deceso del pintor italiano (1884 – 1920), figura clave del postimpresionismo francés y uno de los artistas más importantes de la primera mitad del siglo XX. La muestra ofrece la oportunidad de que los visitantes conozcan de cerca la obra de Amedeo Modigliani, piezas que se exhibirán por primera ocasión en México. Asimismo, se presentará en las salas del MPBA la muestra Mexichrome.