Dear All, Thank You So Much for Taking the Time to Read This Early Draft Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

El Museo Mural Diego Rivera Realiza Recorrido En Lengua Náhuatl, En El Contexto Del Día Internacional De Los Museos

Dirección de Difusión y Relaciones Públicas Ciudad de México, a 19 de mayo de 2019 Boletín núm. 713 El Museo Mural Diego Rivera realiza recorrido en lengua náhuatl, en el contexto del Día Internacional de los Museos Este proyecto de inclusión y acceso al arte fortalece el papel de los museos como espacios de encuentro Se trata de un acercamiento a la diversidad cultural del país y a la obra del artista El Museo Mural Diego Rivera celebró con un recorrido guiado en lengua náhuatl en torno al mural Sueño de una tarde dominical en la Alameda Central, que el artista guanajuatense pintara entre julio y septiembre de 1947. El recorrido, además de abordar el contenido de la obra, también alude la historia del recinto. Esta actividad del Instituto Nacional de Bellas Artes y Literatura (INBAL), realizada en el marco del Día Internacional de los Museos, se llevó a cabo en colaboración con el Instituto Nacional de Lenguas Indígenas (INALI). “El proyecto abordó los temas que ofrecemos durante nuestras visitas tradicionales, sólo que en náhuatl. Se habló sobre la historia del mural y de los personajes que aparecen, que fueron protagonistas de la historia de nuestro país. Este es un recorrido no sólo de acercamiento a la obra de Rivera, sino, particularmente, a la diversidad cultural que existe en el país”, señaló en entrevista Marisol Argüelles, directora del recinto. “El mural concentra varias etapas de la historia de México. Se explica el momento histórico, quiénes son los personajes, el papel de éstos dentro de la historia y de la composición pictórica y se alude a algunas reflexiones que el artista hace a través de su obra. -

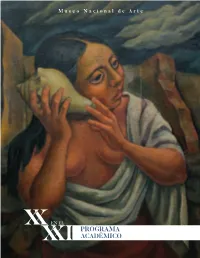

PROGRAMA ACADÉMICO Imagen De Portada

Museo Nacional de Arte PROGRAMA ACADÉMICO Imagen de portada: Gabriel Fernández Ledesma (1900-1983) El mar 1936 Óleo sobre tela INBAL / Museo Nacional de Arte Acervo constitutivo, 1982 PROGRAMA ACADÉMICO Diego Rivera, Roberto Montenegro, Gerardo Murillo, Dr. Atl, Joaquín Clausell, David Alfaro Siqueiros, Lola Cueto, María Izquierdo, Adolfo Best Maugard, Pablo O’Higgins, Francisco Goitia, Jorge González Camarena, Rufino Tamayo, Abraham Ángel, entre muchos otros, serán los portavoces de los grandes cometidos de la plástica nacional: desde los pinceles transgresores de la Revolución Mexicana hasta los neomexicanismos; de las Escuelas al Aire Libre a las normas metódicas de Best Maugard; del dandismo al escenario metafísico; del portentoso género del paisaje al universo del retrato. Una reflexión constante que lleva, sin miramientos, del XX al XXI. Lugar: Museo Nacional de Arte Auditorio Adolfo Best Maugard Horario: Todos los martes de octubre y noviembre De 16:00 a 18:00 h Entrada libre XX en el XXI OCTUBRE 1 de octubre Conversatorio XX en el XXI Ponentes: Estela Duarte, Abraham Villavicencio y David Caliz, curadores de la muestra. Se abordarán los grandes ejes temáticos que definieron la investigación, curaduría y selección de obras para las salas permanentes dedicadas al arte moderno nacional. 8 de octubre Decadentismo al Modernismo nacionalista. Los modos de sentir del realismo social entre los siglos XIX y XX Ponente: Víctor Rodríguez, curador de arte del siglo XIX del MUNAL La ponencia abordará la estética finisecular del XIX, con los puentes artísticos entre Europa y México, que anunciaron la vanguardia en la plástica nacional. 15 de octubre La construcción estética moderna. -

La Voz De Esperanza

I must confess that I’m not great at math (though, I thought I was). I thought we were celebrating 20 years of Calaveras in La Voz this year! The frst issue of Calaveras appeared in November, 1999. The Math La Voz de says it’s been twenty years (2019-1999 = 20)—but my fngers say twenty-one! If you count the frst Esperanza issue starting in 1999 and continue on your fngers November, 2019 to 2019, it’s 21 years of Calaveras! So we missed the Vol. 32 Issue 9 20th! Still, we must celebrate! And we are—starting Editor: Gloria A. Ramírez with the cover of this issue. Design: Elizandro Carrington Cover Art: Dream of a Sunday Afternoon in Diego Rivera’s, Dream of a Sunday Afternoon in Alameda Central Park (Sueño de Alameda Central Park /Sueño de una tarde una tarde dominical en la Alameda Central) painted circa 1947 is a massive mural, dominical en la Alameda Central by Diego Rivera 4.8 x 15 meters, located at the Museo Mural Diego Rivera in Mexico City, next to Contributors the Alameda Park in my favorite part of Mexico City, Centro Historico, the historic Gloria Almaraz, Ellen Riojas Clark, Victor M. center of Mexico. The mural depicts famous people and events in Mexico’s history Cortez, Moisés Espino del Castillo, Anel Flores, Ashley G., Rachel Jennings, Pablo Martinez, from conquest to colonization and the Mexican Revolution happening all at once—as Dennis Medina, Adriana Netro, Kamala Platt, hundreds of famous personalities stroll through or spend time at the Alameda Central Rosemary Reyna-Sánchez, Carla Rivera, Norma Park that was created in 1592. -

Angelina Beloff Como Misionera Cultural: Una Revalorización De Su Arte»

GUERRERO OLAVARRIETA, Ana Paula (2017). «Angelina Beloff como misionera cultural: una revalorización de su arte». Monograma. Revista Iberoamericana de Cultura y Pensamiento, n. 1, pp. 177-193. URL: http://revistamonograma.com/index.php/mngrm/article/view/12 FECHA DE RECEPCIÓN: 17/10/2017 · FECHA DE ACEPTACIÓN: 7/11/2017 ISSN: 2603-5839 Angelina Beloff como misionera cultural: una revalorización de su arte Ana Paula GUERRERO OLAVARRIETA Universidad Iberoamericana, Ciudad de México [email protected] Resumen: ¿Por qué estudiar a Angelina Beloff? ¿Qué relación tiene con el contexto mexicano? Los estudios que hay acerca de Angelina Beloff se han centrado bajo la sombra de Diego Rivera, con quien tuvo una relación de diez años. Por consiguiente, la investigación está encaminada a tener un acercamiento más crítico a su obra y a su desempeño laboral en Europa y en México del siglo XX. La presente investigación busca rescatar a Beloff dentro del contexto de los artistas mexicanos de la época. Sin hacer un recuento biográfico, toma como referencia diversos textos que la mencionan, para sustentar y debatir junto con los que han excluido la figura de Beloff dentro de la historiografía mexicana. Asimismo explica por qué es relevante estudiar a esta artista extranjera que decidió vivir en nuestro país junto con otras figuras del medio artístico contemporáneo. Palabras clave: Angelina Beloff, extranjera, arte mexicano, exclusión, historiografía. Abstract: Why study Angelina Beloff? What relationship does she has with the Mexican context? Studies about Angelina Beloff have been centered under Diego Rivera's shadow, with whom she had a relationship for ten years. Therefore, the investigation is driven to have a more critical close up to her art work and her job performance in Europe and Mexico during the Twentieth Century. -

Diplomova Prace

f UNIVERZITA KARLOVA V PRAZE Filozoficka fakulta DIPLOMovA PRAcE 2006 Petra BINKOvA ,.... Charles University in Prague Faculty of Philosophy & Arts Center for Ibero-American Studies Petra Bin k 0 v a The 20th Century Muralism in Mexico Ibero-American Studies Supervisor: Prof. Dr. Josef Opatrny 2005 1 I ! , i Prohlasuji, ze jsem disertacni praci vykonala samostatne s vyuzitim uvedenych pramenu a literatury. V Praze dne 25.1edna 2006 Petra Binkova , ) , ," ! !I·' ' i 2 i L Insanity: doing the same thing over and over again and expecting different results. Albert Einstein To J.M., R.S. and V.V . ... because of all of you, I do feel sane. 3 L LIST OF CONTENTS Introduction ..............................................................................05 Chapter I Mexican Mural Renaissance and an Apex of the Mexican School ...................................................... 15 Chapter II The Mexican School after 1950: Facing the Rupture ..................................................................................... 32 Chapter III Mexican Muralism After the Mexican School (1970s-1980s) ......................................................................... 51 Chapter IV Mexican Muralism After the Mexican School (1990s) .......................................................................71 Chapter V Mexican Muralism After the Mexican School: The Most Recent Developments ......................................... 89 Conclusion ............................................................................. 116 Bibliography .......................................................................... -

La Secretaría De Cultura Da Conocer Nombramientos En Museos Del INBAL

Comunicado No. 79 Ciudad de México, viernes 15 de febrero de 2019 La Secretaría de Cultura da conocer nombramientos en compañías y museos del INBAL Las compañías artísticas promoverán nuevos esquemas de producción artística, una perspectiva nacional, enfoques de inclusión social, igualdad e interdisciplina Se creará la Red Nacional de Museos para fortalecer su gestión y mejores prácticas de servicio La Directora General del Instituto Nacional de Bellas Artes y Literatura (INBAL), doctora Lucina Jiménez, por acuerdo con la Secretaria de Cultura, licenciada Alejandra Frausto, en cumplimiento con la normatividad vigente, y luego de diversos diálogos con comunidades artísticas, da a conocer nuevos nombramientos y confirmaciones de las personas que tendrán la responsabilidad de fortalecer la promoción nacional e internacional de las compañías artísticas, así como la vocación de los 18 espacios museísticos que dependen del INBAL, con especial énfasis en la recuperación del diálogo entre el arte moderno y el arte contemporáneo mexicano, el manejo de sus colecciones, así como las itinerancias nacionales e internacionales. Compañías Artísticas Las compañías artísticas del Instituto han iniciado la redefinición de los modelos de producción artísticas de sus respectivas disciplinas que tomarán en cuenta la itinerancia nacional, la coproducción nacional e internacional, la interdisciplina, así como enfoques de promoción de la igualdad y la inclusión social. En la Compañía Nacional de Danza se crea una Codirección, la cual tendrán a su cargo la -

Catrinas Y Judas En El Universo Decorativo Del Estudio De Diego Rivera Catrinas and Judas in the Decorative Universe of Diego Rivera´S Studio

Res Mobilis Revista internacional de investigación en mobiliario y objetos decorativos Vol. 8, nº. 9, 2019 CATRINAS Y JUDAS EN EL UNIVERSO DECORATIVO DEL ESTUDIO DE DIEGO RIVERA CATRINAS AND JUDAS IN THE DECORATIVE UNIVERSE OF DIEGO RIVERA´S STUDIO Ariadna Ruiz Gómez1 Universidad Complutense Madrid Resumen El artista mexicano Diego Rivera encargó dos viviendas para él y Frida Kahlo al arquitecto Juan O´Gorman, quien les realizó un proyecto completamente moderno, usando un lenguaje lecorbusiano basado en un funcionalismo radical, de paramentos lisos, sin decoración. En el interior sigue las mismas premisas y diseña desde el fregadero de la cocina a los muebles, todo dentro de una estética minimalista y sencilla. Lo que sorprende al estudiar el mobiliario y los elementos decorativos del estudio de Rivera es que han perdurado los muebles de metal que diseñó O´Gorman, además de los que el muralista fue comprando, la mayoría realizados por artesanos este punto en el que centramos nuestra investigación, el que Rivera adornó su estudio con más de 140 enormes piezas, algunas de más de dos metros de altura, realizadas en cartón, que representan esqueletos y figuras de judas. Palabras clave: Diego Rivera, Frida Kahlo, catrinas, Judas, cartonería Abstract The Mexican artist Diego Rivera ordered the houses for Frida Kahlo and himself to the architect Juan O´Gorman who makes a project completely modern, using a Lecorbusian language based on a radical style smooth walls, without any decoration. Inside he follows the same principles and designs from the kitchen sink to the furniture; everything is done in a simple and minimalist way. -

World History Unit 03 2013-2014.Indd

Unit 03, Class 15 The Mexican Revolution: Peace, Bread and Land 2013-2014 worldHistory Purpose: Do well fed people start revolutions? Part One: Homework After reading the assigned sections, complete the tasks that follow. The Mexican revolution, p. 722 Remembering the Revolution, p. 723 Reforms in Mexico, p. 724 1. What were the main ideas of the revolt in Mexico? Create three posters below that might be carried in a protest by a poor Mexican. It may be a phrase or a single word. 2. What is a villista? 309 3. The pictures below represent significant persons of the revolution time. Next to each picture, write a two sentence summary of that person’s actions during the period of the 1910 revolution. Porfirio Diaz Francisco Madero Emiliano Zapata 310 Part Two: The Revolution Section A: Video on Mexican Revolution Examine the video and take brief notes on the time period called the Porfiriato. Section B: Visualizing the Mexican Revolution Diego Rivera (December 8, 1886 – November 24, 1957) was a prominent Mexican painter and the hus- band of Frida Kahlo. His large wall works in fresco helped establish the Mexican Mural Movement in Mexican art. Between 1922 and 1953, Rivera painted murals among others in Mexico City, Chapingo, Cuernavaca, San Francisco, Detroit, and New York City. Sueño de una tarde dominical en la Alameda Central or Dream of a Sunday Afternoon in the Al- ameda Central is a mural created by Diego Rivera. It was painted between the years 1946 and 1947, and is the principal work of the “Museo Mural Diego Rivera” adjacent to the Alameda in the historic center of Mexico City. -

México Mágico: Magical Mexico City Exploring the Colors of Mexican Folk Art with Marina Aguirre and Dr. Khristaan Villela

México Mágico: Magical Mexico City Exploring the Colors of Mexican Folk Art With Marina Aguirre and Dr. Khristaan Villela For the Friends of Folk Art - Santa Fe, NM September 4 – 12, 2017 Join the Friends of Folk Art and MOIFA’s Director for a special journey to Mexico Day 1 – Monday, September 4 Arrive México City in the afternoon. Transfer to our centrally located accommodations at the Best Western Majestic Hotel. Dinner on your own Day 2 – Tuesday, September 5 Breakfast at hotel is included daily Visit and tour of Museo de Arte Popular (Folk Art Museum) Lunch at Casa de los Azulejos, “House of Tiles, an 18th century palace (included) Afternoon visit to National Museum of Anthropology, one of the most important museums in the world, and home to Mexico’s national collection of Precolumbian art. Our tour will focus on Mexico’s rich indigenous arts and its connection and historic roots in Mexican folk art. There will not be time to see the entire museum. Dinner at Bonito Restaurant in the Condesa neighborhood (included) 1 Day 3 – Wednesday, September 6 Breakfast at hotel Visit to Diego Rivera’s mural “Dream of a Sunday Afternoon in Alameda Central Park” at the Museo Mural Diego Rivera. The mural provides an introduction to Mexico’s history and is an important point of reference for the work of Diego Rivera. The museum is a 30-minute walk from the hotel so you can walk or ride in the van. Visit the private collection of Ruth Lechuga at the Franz Mayer Museum. This collection is only available to scholars, and we have a rare opportunity to enjoy one of the most important folk art collections in Mexico. -

Portraits and Self-Portraits by Diego Rivera and Frida Kahlo1

PERFormiNG THE SELF AND THE OTHER: PorTraiTS AND SELF-PorTraiTS BY DiEGO RIVEra AND FriDA KahLO1 Ellen G. Landau "The Strange Couple from the Land Like Nefertiti and, of course, Frida of the Dot and the Line": although Kahlo herself, Neferisis has thick con- Frida Kahlo used this inscription on spicuous eyebrows. Ojo único, unlike one page of her journal to identify an Akhenaton, has a full fleshy look; so imaginary Egyptian couple she depict- too his child and baby Moses. All ed in accompanying drawings, there is three, in fact, more or less share the little doubt that she intended it to facial qualities of Diego Rivera, Frida have a personal double meaning.2 Kahlo’s husband (whom she actu- Playing both visually and linguis- tically on Amarna ruler Akhenaton 1 This essay was written as a lecture for and his famous consort, Kahlo no the international symposium Diego Rivera: A Transcultural Dialogue, held at the Cleveland doubt generated her fictional charac- Museum of Art (CMA) in February 1999 in ters, Ojo único, Neferisis, and their little conjunction with the opening of Diego Rivera: son, through a multi-layered process Art and Revolution, co-organized by INBA and CMA. I am indebted to William H. Robinson, of psychic associations. Indeed, flanking CMA Associate Curator of Modern Art, for the central fetus, the real historical inviting me to speak on this topic at the sym- spouses face each other in Kahlo’s posium. I would also like to thank Irene Herner, Moses, or Nucleus of Creation, a can- Debby Tenenbaum, and Amy Reed Frederick, as well as Bertha Cea of the American Embassy vas painted in 1945 (probably around in Mexico City, for helping to make this essay the time of her undated diary entry); possible, and Leticia López Orozco for inviting and a contemporaneous statement me to publish it in Crónicas. -

Translating Revolution: U.S

A Spiritual Manifestation of Mexican Muralism Works by Jean Charlot and Alfredo Ramos Martínez BY AMY GALPIN M.A., San Diego State University, 2001 B.A., Texas Christian University, 1999 THESIS Submitted as partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Art History in the Graduate College of the University of Illinois at Chicago, 2012 Chicago, Illinois Defense Committee: Hannah Higgins, Chair and Advisor David M. Sokol Javier Villa-Flores, Latin American and Latino Studies Cristián Roa-de-la-Carrera, Latin American and Latino Studies Bram Dijkstra, University of California San Diego I dedicate this project to my parents, Rosemary and Cas Galpin. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS My committee deserves many thanks. I would like to recognize Dr. Hannah Higgins, who took my project on late in the process, and with myriad commitments of her own. I will always be grateful that she was willing to work with me. Dr. David Sokol spent countless hours reading my writing. With great humor and insight, he pushed me to think about new perspectives on this topic. I treasure David’s tremendous generosity and his wonderful ability to be a strong mentor. I have known Dr. Javier Villa-Flores and Dr. Cristián Roa-de-la-Carrera for many years, and I cherish the knowledge they have shared with me about the history of Mexico and theory. The independent studies I took with them were some of the best experiences I had at the University of Illinois-Chicago. I admire their strong scholarship and the endurance they had to remain on my committee. -

Encuentro En Ávila Con La Pintura De Diego Rivera

ENCUENTRO EN ÁVILA CON LA PINTURA DE DIEGO RIVERA Por Jesús Mª Sanchidrián Gallego INTINERARIO 1. Aproximación a la pintura de Diego Rivera en Ávila. 2. Primeros años y paso por la Academia con Ávila expuesta. 3. Rivera navega rumbo a España. 4. En el taller de Eduardo Chicharro y Agüera. 5. Ávila inunda el estudio de Chicharro donde pinta Rivera. 6. Ávila modelo pictórico de Rivera. 7. Rivera y Sorolla con Ávila en el horizonte. 8. Ávila y periodo Zuloaga en la pintura de Rivera. 1. APROXIMACIÓN A LA PINTURA DE DIEGO RIVERA EN ÁVILA. 9. En la exposición de los discípulos de Chicharro. 10. En la Exposición Nacional de Bellas Artes. “Encuentro en Ávila con la pintura de Diego Rivera” es el título de la 11. En la Exposición Hispano-Francesa de Zaragoza. conferencia impartida el 18 de diciembre de 2014 en el Episcopio de 12. Con el abulense electo Mariano José de Larra. Ávila, la cual trató sobre el granito de arena que Ávila representó en la dilatada trayectoria artística del pintor Diego Rivera Barrientos (1886- 13. Ávila en las letras mexicanas. 1957). 14. De tertulia en los cafés madrileños con literatos y pintores. Fueron apenas unos meses veraniegos del periodo 1907-1908, 15. Ávila en Centenario de la Independencia de México. tiempo en el que el pintor tuvo contacto con esta ciudad castellana de raigambre medieval y viejas tradiciones que se asoma al valle Amblés, 16. Ávila al margen del riverismo y las nuevas tendencias. paisaje que a Rivera le recuerda su tierra natal y le transporta al 17.