The Journal of the International Oak

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Department of Planning and Zoning

Department of Planning and Zoning Subject: Howard County Landscape Manual Updates: Recommended Street Tree List (Appendix B) and Recommended Plant List (Appendix C) - Effective July 1, 2010 To: DLD Review Staff Homebuilders Committee From: Kent Sheubrooks, Acting Chief Division of Land Development Date: July 1, 2010 Purpose: The purpose of this policy memorandum is to update the Recommended Plant Lists presently contained in the Landscape Manual. The plant lists were created for the first edition of the Manual in 1993 before information was available about invasive qualities of certain recommended plants contained in those lists (Norway Maple, Bradford Pear, etc.). Additionally, diseases and pests have made some other plants undesirable (Ash, Austrian Pine, etc.). The Howard County General Plan 2000 and subsequent environmental and community planning publications such as the Route 1 and Route 40 Manuals and the Green Neighborhood Design Guidelines have promoted the desirability of using native plants in landscape plantings. Therefore, this policy seeks to update the Recommended Plant Lists by identifying invasive plant species and disease or pest ridden plants for their removal and prohibition from further planting in Howard County and to add other available native plants which have desirable characteristics for street tree or general landscape use for inclusion on the Recommended Plant Lists. Please note that a comprehensive review of the street tree and landscape tree lists were conducted for the purpose of this update, however, only -

Quercus Cerris

Quercus cerris Quercus cerris in Europe: distribution, habitat, usage and threats D. de Rigo, C. M. Enescu, T. Houston Durrant, G. Caudullo Turkey oak (Quercus cerris L.) is a deciduous tree native to southern Europe and Asia Minor, and a dominant species in the mixed forests of the Mediterranean basin. Turkey oak is a representative of section Cerris, a particular section within the genus Quercus which includes species for which the maturation of acorns occurs in the second year. Quercus cerris L., commonly known as Turkey oak, is a large fast-growing deciduous tree species growing to 40 m tall with 1 Frequency a trunk up to 1.5-2 m diameter , with a well-developed root < 25% system2. It can live for around 120-150 years3. The bark is 25% - 50% 50% - 75% mauve-grey and deeply furrowed with reddish-brown or orange > 75% bark fissures4, 5. Compared with other common oak species, e.g. Chorology Native sessile oak (Quercus petraea) and pedunculate oak (Quercus Introduced robur), the wood is inferior, and only useful for rough work such as shuttering or fuelwood1. The leaves are dark green above and grey-felted underneath6; they are variable in size and shape but are normally 9-12 cm long and 3-5 cm wide, with 7-9 pairs of triangular lobes6. The leaves turn yellow to gold in late autumn and drop off or persist in the crown until the next spring, especially on young trees3. The twigs are long and pubescent, grey or olive-green, with lenticels. The buds, which are concentrated Large shade tree in agricultural area near Altamura (Bari, South Italy). -

Sawtooth Oak Planting Guide

Planting Guide and into southern New England (USDA plant hardiness zones 5b through 8b). On exposed sites in SAWTOOH OAK the northern Finger Lakes Region of New York, it may winterkill. Sawtooth oak is winter hardy and Quercus acutissima can be grown in droughty and well-drained soils from Carruthers sandy loam to clay loam. However, the best performance is achieved in deep, well-drained soils. plant symbol = QUAC80 It can also be grown on reclaimed surface mined land where favorable moisture conditions are present and pH is above 5.0. For a current distribution map, please consult the Plant Profile page for this species on the PLANTS Website. Establishment Sawtooth oak may be established, from bareroot seedlings, containerized plants, or acorns. One year old bareroot seedlings or containerized plants should be planted 15-20 feet apart for maximum acorn production. In areas where multiple rows are used, the spacing should be no less than 20 feet apart. In seed orchards, there should be at least 15 plants per C. Miller USDA NRCS planting for effective wind pollination. Uses Bareroot seedlings must be planted while the plants The primary use for this species is as a wildlife food are dormant (from the average date of first frost in source and cover. It is also a good shade tree. the fall until the average date of last frost in the spring). Containerized plants may be planted later in the spring, but may require frequent irrigation to Status survive. Please consult the PLANTS Web site and your State Department of Natural Resources for this plant’s Sites for landscape plantings and seed orchards current status (e.g. -

Species List

1 of 16 Claypits 20/09/2021 species list Group Taxon Common Name Earliest Latest Records acarine Aceria macrorhyncha 2012 2012 1 acarine Aceria nalepai 2018 2018 1 amphibian Bufo bufo Common Toad 2001 2018 6 amphibian Lissotriton helveticus Palmate Newt 2001 2018 5 amphibian Lissotriton vulgaris Smooth Newt 2001 2001 1 annelid Hirudinea Leech 2011 2011 1 bird Acanthis cabaret Lesser Redpoll 2013 2013 1 bird Acrocephalus schoenobaenus Sedge Warbler 2001 2011 2 bird Aegithalos caudatus Long-tailed Tit 2011 2014 2 bird Alcedo atthis Kingfisher 2020 2020 1 bird Anas platyrhynchos Mallard 2013 2018 4 bird Anser Goose 2011 2011 1 bird Ardea cinerea Grey Heron 2013 2013 1 bird Aythya fuligula Tufted Duck 2013 2014 1 bird Buteo buteo Buzzard 2013 2014 2 bird Carduelis carduelis Goldfinch 2011 2014 5 bird Chloris chloris Greenfinch 2011 2014 6 bird Chroicocephalus ridibundus Black-headed Gull 2014 2014 1 bird Coloeus monedula Jackdaw 2011 2013 2 bird Columba livia Feral Pigeon 2014 2014 1 bird Columba palumbus Woodpigeon 2011 2018 8 bird Corvus corax Raven 2020 2020 1 bird Corvus corone Carrion Crow 2011 2014 5 bird Curruca communis Whitethroat 2011 2014 4 bird Cyanistes caeruleus Blue Tit 2011 2014 6 bird Cygnus olor Mute Swan 2013 2014 4 bird Delichon urbicum House Martin 2011 2011 1 bird Emberiza schoeniclus Reed Bunting 2013 2014 2 bird Erithacus rubecula Robin 2011 2014 7 bird Falco peregrinus Peregrine 2013 2013 1 bird Falco tinnunculus Kestrel 2010 2020 3 bird Fringilla coelebs Chaffinch 2011 2014 7 bird Gallinula chloropus Moorhen 2013 -

Phytophthora Ramorum Sudden Oak Death Pathogen

NAME OF SPECIES: Phytophthora ramorum Sudden Oak Death pathogen Synonyms: Common Name: Sudden Oak Death pathogen A. CURRENT STATUS AND DISTRIBUTION I. In Wisconsin? 1. YES NO X 2. Abundance: 3. Geographic Range: 4. Habitat Invaded: 5. Historical Status and Rate of Spread in Wisconsin: 6. Proportion of potential range occupied: II. Invasive in Similar Climate YES NO X Zones United States: In 14 coastal California Counties and in Curry County, Oregon. In nursery in Washington. Canada: Nursery in British Columbia. Europe: Germany, the Netherlands, the United Kingdom, Poland, Spain, France, Belgium, and Sweden. III. Invasive in Similar Habitat YES X NO Types IV. Habitat Affected 1. Habitat affected: this disease thrives in cool, wet climates including areas in coastal California within the fog belt or in low- lying forested areas along stream beds and other bodies of water. Oaks associated with understory species that are susceptible to foliar infections are at higher risk of becoming infected. 2. Host plants: Forty-five hosts are regulated for this disease. These hosts have been found naturally infected by P. ramorum and have had Koch’s postulates completed, reviewed and accepted. Approximately fifty-nine species are associated with Phytophthora ramorum. These species are found naturally infected; P. ramorum has been cultured or detected with PCR but Koch’s postulates have not been completed or documented and reviewed. Northern red oak (Quercus rubra) is considered an associated host. See end of document for complete list of plant hosts. National Risk Model and Map shows susceptible forest types in the mid-Atlantic region of the United States. -

Quercus Robur (Fagaceae)

Quercus robur (Fagaceae) The map description EEBIO area The integrated map shows the distribution and changes in the areal’s boundaries of pedunculate oak (Quercus robur). Q. robur is the dominant forest- formative species in the belt of broadleaf and mixed 4 needleleaf-broadleaf forests in the plains of the European part of the former USSR (Sokolov et al. 1977). In the northern part of its areal Q. robur grows in river valleys. In the central part, it forms mixed forests with Picea abies; closer to the south – a belt of broadleaf forests where Q. robur dominates. At the areal’s south boundary it forms small (marginal) forests in ravines and flood-plains (Atlas of Areals and Resources… , 1976). Q. robur belongs to the thermophilic species. The low temperature bound of possible occurrence of oak forests is marked by an average annual of 2?C l (http://www.forest.ru – in Russian). Therefore, l l l l l l hypotretically, oak areal boundaries will shift along l ll l l l l l l l with the changes in the average annual temperature. l l l l l l l l l l l For Yearly map of averaged mean annual air l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l lll temperature (Afonin A., Lipiyaynen K., Tsepelev V., l l l l l l l ll ll l l l 2005) see http://www.agroatlas.spb.ru Climate. l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l Oak forests are of great importance for the water l l l l l ll l lll l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l regime and soil structure, especially on the steep l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l slopes of river valleys and in forest-poor areas. -

5 Fagaceae Trees

CHAPTER 5 5 Fagaceae Trees Antoine Kremerl, Manuela Casasoli2,Teresa ~arreneche~,Catherine Bod6n2s1, Paul Sisco4,Thomas ~ubisiak~,Marta Scalfi6, Stefano Leonardi6,Erica ~akker~,Joukje ~uiteveld', Jeanne ~omero-Seversong, Kathiravetpillai Arumuganathanlo, Jeremy ~eror~',Caroline scotti-~aintagne", Guy Roussell, Maria Evangelista Bertocchil, Christian kxerl2,Ilga porth13, Fred ~ebard'~,Catherine clark15, John carlson16, Christophe Plomionl, Hans-Peter Koelewijn8, and Fiorella villani17 UMR Biodiversiti Genes & Communautis, INRA, 69 Route d'Arcachon, 33612 Cestas, France, e-mail: [email protected] Dipartimento di Biologia Vegetale, Universita "La Sapienza", Piazza A. Moro 5,00185 Rome, Italy Unite de Recherche sur les Especes Fruitikres et la Vigne, INRA, 71 Avenue Edouard Bourlaux, 33883 Villenave d'Ornon, France The American Chestnut Foundation, One Oak Plaza, Suite 308 Asheville, NC 28801, USA Southern Institute of Forest Genetics, USDA-Forest Service, 23332 Highway 67, Saucier, MS 39574-9344, USA Dipartimento di Scienze Ambientali, Universitk di Parma, Parco Area delle Scienze 1lIA, 43100 Parma, Italy Department of Ecology and Evolution, University of Chicago, 5801 South Ellis Avenue, Chicago, IL 60637, USA Alterra Wageningen UR, Centre for Ecosystem Studies, P.O. Box 47,6700 AA Wageningen, The Netherlands Department of Biological Sciences, University of Notre Dame, Notre Dame, IN 46556, USA lo Flow Cytometry and Imaging Core Laboratory, Benaroya Research Institute at Virginia Mason, 1201 Ninth Avenue, Seattle, WA 98101, -

West-Side Prairies & Woodlands

Washington State Natural Regions Beyond the Treeline: Beyond the Forested Ecosystems: Prairies, Alpine & Drylands WA Dept. of Natural Resources 1998 West-side Prairies & Woodlands Oak Woodland & Prairie Ecosystems West-side Oak Woodland & Prairie Ecosystems in Grey San Juan Island Prairies 1. South Puget Sound prairies & oak woodlands 2. Island / Peninsula coastal prairies & woodlands Olympic Peninsula 3. Rocky balds Prairies South Puget Prairies WA GAP Analysis project 1996 Oak Woodland & Prairie Ecosystems San Juan West-side Island South Puget Sound Prairie Ecosystems Oak Woodland & Prairie Prairies Ecosystems in Grey Grasslands dominated by Olympic • Grasses Peninsula Herbs Prairies • • Bracken fern South • Mosses & lichens Puget Prairies With scattered shrubs Camas (Camassia quamash) WA GAP Analysis project 1996 •1 South Puget Sound Prairie Ecosystems South Puget Sound Prairie Ecosystems Mounded prairie Some of these are “mounded” prairies Mima Mounds Research Natural Area South Puget Sound Prairie Ecosystems South Puget Sound Prairie Ecosystems Scattered shrubs Lichen mats in the prairie Serviceberry Cascara South Puget Sound Prairie Ecosystems South Puget Sound Prairie Ecosystems As unique ecosystems they provide habitat for unique plants As unique ecosystems they provide habitat for unique critters Camas (Camassia quamash) Mazama Pocket Gopher Golden paintbrush Many unique species of butterflies (Castilleja levisecta) (this is an Anise Swallowtail) Photos from Dunn & Ewing (1997) •2 South Puget Sound Prairie Ecosystems Fire is -

New York City Approved Street Trees

New York City Approved Street Trees Suggested Tree Species Shape Visual interest Frequency of Preferred Cultivars Notes Scientific Name Common Name Planting Acer rubrum Red Maple Sparingly 'Red Sunset' ALB Host Aesculus hippocastanum Horsechestnut White May flowers Sparingly 'Baumanni' ALB Host Aesculus octandra Yellow Buckeye Yellow May Flowers Sparingly ALB Host ALB Host 'Duraheat' Betula nigra River Birch Ornamental Bark Sparingly Plant Single Stem 'Heritage' Only Celtis occidentalis Hackberry Ornamental Bark Sparingly 'Magnifica' ALB Host ALB Host Cercidiphyllum japonicum Katsura Tree Sparingly Plant Single Stem Only Corylus colurna Turkish Filbert Sparingly LARGE TREES: Mature LARGE TREES: height than greater feet 50 tall Eucommia ulmoides Hardy Rubber Tree Frequently 'Asplenifolia' Fagus sylvatica European Beech Sparingly 'Dawyckii Purple' 'Autumn Gold' Ginkgo biloba Ginkgo Yellow Fall Color Moderately 'Magyar' Very Tough Tree 'Princeton Sentry' 'Shademaster' 'Halka' Gleditsia triacanthos var inermis Honeylocust Yellow Fall Color Moderately 'Imperial' 'Skyline' 'Espresso' Gymnocladus dioicus Kentucky Coffeetree Large Tropical Leaves Frequently 'Prairie Titan' Page 1 of 7 New York City Approved Street Trees Suggested Tree Species Shape Visual interest Frequency of Preferred Cultivars Notes Scientific Name Common Name Planting 'Rotundiloba' Seedless Cultivars Liquidambar styraciflua Sweetgum Excellent Fall Color Frequently 'Worplesdon' Preffered 'Cherokee' Orange/Green June Liriodendron tulipifera Tulip Tree Moderately Flowers Metasequoia -

Oaks (Quercus Spp.): a Brief History

Publication WSFNR-20-25A April 2020 Oaks (Quercus spp.): A Brief History Dr. Kim D. Coder, Professor of Tree Biology & Health Care / University Hill Fellow University of Georgia Warnell School of Forestry & Natural Resources Quercus (oak) is the largest tree genus in temperate and sub-tropical areas of the Northern Hemisphere with an extensive distribution. (Denk et.al. 2010) Oaks are the most dominant trees of North America both in species number and biomass. (Hipp et.al. 2018) The three North America oak groups (white, red / black, and golden-cup) represent roughly 60% (~255) of the ~435 species within the Quercus genus worldwide. (Hipp et.al. 2018; McVay et.al. 2017a) Oak group development over time helped determine current species, and can suggest relationships which foster hybridization. The red / black and white oaks developed during a warm phase in global climate at high latitudes in what today is the boreal forest zone. From this northern location, both oak groups spread together southward across the continent splitting into a large eastern United States pathway, and much smaller western and far western paths. Both species groups spread into the eastern United States, then southward, and continued into Mexico and Central America as far as Columbia. (Hipp et.al. 2018) Today, Mexico is considered the world center of oak diversity. (Hipp et.al. 2018) Figure 1 shows genus, sub-genus and sections of Quercus (oak). History of Oak Species Groups Oaks developed under much different climates and environments than today. By examining how oaks developed and diversified into small, closely related groups, the native set of Georgia oak species can be better appreciated and understood in how they are related, share gene sets, or hybridize. -

Designing Hardwood Tree Plantings for Wildlife Brian J

FNR-213 Hardwood Tree Improvement and Regeneration Center North Central Research Station USDA Forest Service Department of Forestry and Natural Resources Purdue University Designing Hardwood Tree Plantings for Wildlife Brian J. MacGowan, Department of Forestry and Natural Resources, Purdue University Woody plants can be of value to many wildlife species. The species of tree or shrub, or the location, size, and shape of planting can all have an impact on wildlife. The purpose of this paper is to discuss the benefits of trees and shrubs for wildlife and how to design tree and shrub plantings for wildlife. Some of the practices may conflict with other management goals and may have to be modified for individual priorities. Trees and Shrubs for Wildlife The species you select for a tree planting should depend on the growing conditions of the site and the wildlife species that you want to manage. Talk to a professional forester to help you select the tree species best suited for your growing conditions. A professional biologist, such as a Department of Natural Resources District Biologist (www.in.gov/ food source for wildlife (Table 2). Shrubs can be dnr/fishwild/huntguide1/wbiolo.htm), can assist you particularly important because several species of with planning a tree planting for wildlife. wildlife, especially songbirds, prefer to feed or nest There is no specific formula for developing wild- on or near the ground. Shrubs also provide good life habitat. For example, acorns are eaten by a wide protective cover for these types of wildlife. Pines variety of wildlife species including tree squirrels, and other softwoods provide limited food, but are an pheasants, wild turkey, and deer. -

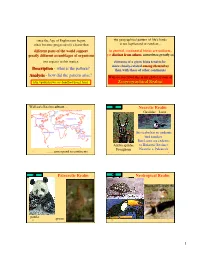

Description - What Is the Pattern? Than with Those of Other Continents

since the Age of Exploration began, the geographical pattern of life's kinds it has become progressively clearer that is not haphazard or random... different parts of the world support in general, continental biotas are uniform, greatly different assemblages of organisms yet distinct from others, sometimes greatly so two aspects to this matter: elements of a given biota tend to be more closely-related among themselves Description - what is the pattern? than with those of other continents Analysis - how did the pattern arise? Wallace described this in his global system of http://publish.uwo.ca/~handford/zoog1.html Zoogeographical Realms 15 1 15 Zoogeographical Realms 2 Wallace's Realms almost..... Nearctic Realm Gaviidae - Loon this realm has no endemic bird families. But Loons are endemic Antilocapridae to Holarctic Realm = Pronghorn Nearctic + Palearctic 15 .........correspond to continents 3 15 4 Palearctic Realm Neotropical Realm this realm is truly the "bird-realm" a great number of among the many families are endemic endemic families including tinamous are anteaters and and toucans cavies panda 15 grouse 5 15 6 1 Ethiopian Realm Oriental Realm gibbon leafbird aardvark 15 lemur ostrich 7 15 8 Australasian Realm so continental biotas are distinct; Monotremes - but they are not equally distinct egg-laying mammals 79 families of terrestrial mammals RE GIONS! near.! neotr. palæar. ethio. orien. austr. nearctic! ! ! 4! ! ! ! 51/79! = 73% endemic neotropical! ! 6! 15!! ! ! to realms platypus palæarctic! ! 5! 2! 1! ! ! ethiopean! ! 0! 0!