Designing Hardwood Tree Plantings for Wildlife Brian J

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Survival and Initial Growth Attributes of Improved and Unimproved Cherrybark Oak in South Arkansas

SURVIVAL AND INITIAL GROWTH ATTRIBUTES OF IMPROVED AND UNIMPROVED CHERRYBARK OAK IN SOUTH ARKANSAS Joshua P. Adams, David Graves, Matthew H. Pelkki, Chris Stuhlinger, and Jon Barry1 Abstract--Thousands of acres are planted every year with genetically improved seedlings; but while pine continues to be extensively explored, the same is not true for hardwoods due to costs and rotation length. An improved cherrybark oak (Quercus pagoda Raf.) seed orchard exists in North Little Rock, AR, providing an opportunity to evaluate hardwood improvement. However, the cost and limited testing of these seedlings have been large limiting factors in their deployment. In February 2012, improved and woods-run seedlings were hand-planted at two sites in southern Arkansas including a site near Hope, AR, and one near Monticello, AR. The sites were treated with 2 ounces per acre of Oust XP® 2 weeks after tree planting with manual control of sumac (Rhus spp.) and sweetgum (Liquidambar styraciflua L.) shortly thereafter. A random sample of seedlings at the nursery confirmed that seedling undercutting effectively controlled root length which was statistically the same for both groups at 21.8 inches. However, root collar diameter of an improved seedling was on average 27 percent larger than an unimproved seedling. These trends were similar to those among planted seedlings in which improved seedlings were 9 percent and 8 percent greater in regards to ground line diameter and height, respectively. However, improved seedlings exhibited greater initial mortality, by 6.2 percent, in the first few months of their growing season. While initial mortality is often considered random, disparity between the two groups points to other causes, such as the larger root sizes, which may pose planting problems. -

Sp09-For Web.Pub

Spring 2009 Page 1 Botanic Garden News The Botanic Garden Volume 12, No. 1 of Smith College Spring 2009 Madelaine Zadik “T he tulip is the sexiest, most capricious, the most various, subtle, powerful, and intriguing Room. Many thanks to the Museum of flower on Earth.” These are the words of Anna Art for framing them for us. Pavord, opening speaker for this year’s Spring In our display case are other tulip- Bulb Show. A mainstay of flower shows and related books lent to us by the garden displays, the tulip has come a long way Mortimer Rare Book Room. Flora’s from its humble origins in central Asia to Feast: A Masque of Flowers (1889) is Tulipa ‘Carmen Rio’ becoming a beloved spring icon. Could you opened to the tulip and hyacinth, two of Photograph by Madelaine Zadik imagine spring without tulips? forty full color lithographs in the book Horticulturist and writer extraordinaire Anna Pavord dazzled everyone with her by Walter Crane. Each page presents an talk, The Tulip: The Flower That Made Men Mad. It was more performance than allegory of a popular flower as human, lecture and demonstrated that although tulipmania might have taken over Europe in clad in flowery garments with a short the early seventeenth century, passions today still run quite strong as far as the tulip whimsical verse. Reproductions of is concerned. (For more about Anna Pavord’s visit, see page 7.) During the several of these (see page 6) were tulipmania period in Europe, fortunes rose to soaring heights and then were quickly scattered through the bulb show, to lost, perhaps similar to the Wall Street turbulence we are everyone’s delight. -

Master Plant List

Marianist Environmental Education Center Mount St. John, 4435 E. Patterson Road, Dayton, OH 45430 937/429-3582 FAX: 937/429-3195 [email protected] http://meec.center NATIVE PLANT ORDER FORM 2019 FLOWER FLOWER # # COMMON NAME SCIENTIFIC NAME SUN MOISTURE DATE COLOR Cones Pots WILDFLOWERS NODDING PINK ALLIUM Allium cernuum July-Aug. Pink CANADA ANEMONE Anemone canadensis May-June White n/a WOODLAND THIMBLEWEED Anemone virginiana July-Aug. Green & white WILD COLUMBINE Aquilegia canadensis April-July Scarlet & yellow PALE INDIAN-PLANTAIN Arnoglossum atriplicifolium July-Sept. White SWAMP MILKWEED Asclepias incarnata July-Sept. Pink-purple n/a COMMON MILKWEED Asclepias syriaca June-Aug. Purple-pink BUTTERFLY-WEED Asclepias tuberosa June-Sept. Orange n/a BLUE FALSE INDIGO Baptisia australis May-June Blue-violet n/a WHITE FALSE INDIGO Baptisia lactea June-July White n/a DOWNY WOODMINT Blephilia ciliata June - July Pale purple HAIRY WOODMINT Blephilia hirsuta June-July White & purple TALL BELLFLOWER Campanulastrum June-Sept. Lavender-blue americanum TURTLEHEAD Chelone glabra Aug.-Sept. White PASTURE THISTLE Cirsium discolor July-Oct. Pink BLUE MISTFLOWER Conoclinium coelestinum Aug.-Sept. blue-violet TALL COREOPSIS Coreopsis tripteris Aug.-Sept. Yellow TALL LARKSPUR Delphinium exaltatum July-Aug. Blue-purple PRAIRIE MIMOSA Desmanthus illinoensis July-Aug. White n/a PURPLE CONEFLOWER Echinacea purpurea June-Sept. Purple RATTLESNAKE-MASTER Eryngium yuccifolium July-Sept. White BONESET Eupatorium perfoliatum July-Sept. White FLOWERING SPURGE Euphorbia corollata June-Aug. White n/a HOLLOW-STEMMED JOE-PYE Eutrochium fistulosum July-Sept. Pink-purple n/a WEED SPOTTED JOE-PYE WEED Eutrochium maculatum July-Sept. Pink-purple n/a PURPLE JOE-PYE WEED Eutrochium purpureum July-Sept. -

New York City Approved Street Trees

New York City Approved Street Trees Suggested Tree Species Shape Visual interest Frequency of Preferred Cultivars Notes Scientific Name Common Name Planting Acer rubrum Red Maple Sparingly 'Red Sunset' ALB Host Aesculus hippocastanum Horsechestnut White May flowers Sparingly 'Baumanni' ALB Host Aesculus octandra Yellow Buckeye Yellow May Flowers Sparingly ALB Host ALB Host 'Duraheat' Betula nigra River Birch Ornamental Bark Sparingly Plant Single Stem 'Heritage' Only Celtis occidentalis Hackberry Ornamental Bark Sparingly 'Magnifica' ALB Host ALB Host Cercidiphyllum japonicum Katsura Tree Sparingly Plant Single Stem Only Corylus colurna Turkish Filbert Sparingly LARGE TREES: Mature LARGE TREES: height than greater feet 50 tall Eucommia ulmoides Hardy Rubber Tree Frequently 'Asplenifolia' Fagus sylvatica European Beech Sparingly 'Dawyckii Purple' 'Autumn Gold' Ginkgo biloba Ginkgo Yellow Fall Color Moderately 'Magyar' Very Tough Tree 'Princeton Sentry' 'Shademaster' 'Halka' Gleditsia triacanthos var inermis Honeylocust Yellow Fall Color Moderately 'Imperial' 'Skyline' 'Espresso' Gymnocladus dioicus Kentucky Coffeetree Large Tropical Leaves Frequently 'Prairie Titan' Page 1 of 7 New York City Approved Street Trees Suggested Tree Species Shape Visual interest Frequency of Preferred Cultivars Notes Scientific Name Common Name Planting 'Rotundiloba' Seedless Cultivars Liquidambar styraciflua Sweetgum Excellent Fall Color Frequently 'Worplesdon' Preffered 'Cherokee' Orange/Green June Liriodendron tulipifera Tulip Tree Moderately Flowers Metasequoia -

Evolutionary Ecology of Mast-Seeding in Temperate and Tropical Oaks (Quercus Spp.) Author(S): V

Evolutionary Ecology of Mast-Seeding in Temperate and Tropical Oaks (Quercus spp.) Author(s): V. L. Sork Source: Vegetatio, Vol. 107/108, Frugivory and Seed Dispersal: Ecological and Evolutionary Aspects (Jun., 1993), pp. 133-147 Published by: Springer Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/20046304 Accessed: 23-08-2015 21:54 UTC Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/ info/about/policies/terms.jsp JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Springer is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Vegetatio. http://www.jstor.org This content downloaded from 128.97.245.17 on Sun, 23 Aug 2015 21:54:56 UTC All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions Vegetatio 107/108: 133-147, 1993. T. H. Fleming and A. Estrada (eds). Frugivory and Seed Dispersal: Ecological and Evolutionary Aspects. 133 ? 1993 Kluwer Academic Publishers. Printed in Belgium. Evolutionary ecology of mast-seeding in temperate and tropical oaks (Quercus spp.) V. L. Sork Department of Biology, University ofMissouri-St. Louis, St. Louis, MO 63121, USA Keywords: Acorn production,Mast-fruiting, Mast-flowering, Pollination efficiency, Predator-satiation hypothesis, Quercus Abstract Mast-seeding is the synchronous production of large seed crops within a population or community of two or more species every years. -

Genetic Improvement and Root Pruning Effects on Cherrybark Oak (Quercus Pagoda L.) Seedling Growth and Survival in Southern Arkansas Joshua P

Genetic Improvement and Root Pruning Effects on Cherrybark Oak (Quercus Pagoda L.) Seedling Growth and Survival in Southern Arkansas Joshua P. Adams, Nicholas Mustoe, Don C. Bragg, Matthew H. Pelkki, and Victor L. Ford Associate Professor, School of Agricultural Sciences and Forestry, Louisiana Tech University, Ruston, LA; Forester, U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) Forest Service, Fishlake National Forest, Richfield, UT; Research Forester and Project Leader, USDA Forest Service, Southern Research Station, Monticello, AR; Professor and Associate Director, Arkansas Forest Resources Center, University of Arkansas at Monticello, Monticello, AR; Director and Professor, Southwest Research and Extension Center, University of Arkansas Research and Extension, Little Rock, AR Abstract (Wharton et al. 1982). Among hardwoods, red oaks (Quercus subgroup Erythrobalanus) are ecologically Cherrybark oak is a highly desirable hardwood and economically valuable. Despite the high desir- species across the Southeastern United States. Sil- ability of red oaks, natural regeneration failures in vicultural techniques for establishment have been stands historically dominated by these oaks has been carefully studied, but advances in tree improvement well documented (Clatterbuck and Meadows 1992, have yet to be realized. Cherrybark oak seedlings of Hodges and Janzen 1987, Lorimer 1989, Oliver et al. genetically improved and unimproved stock were 2005). The lack of natural oak regeneration on many tested in field plantings in southern Arkansas and in sites has resulted in some landowners planting oaks a controlled pot study for root pruning effects. After to ensure this taxa remains viable for future genera- 2 years, initial growth advantages of improved stock tions, provides wildlife habitat, conserves the natu- were no longer present; however, improved stock ral environment, and produces high-value products averaged 19 percent higher survival compared with (Michler et al. -

State of New York City's Plants 2018

STATE OF NEW YORK CITY’S PLANTS 2018 Daniel Atha & Brian Boom © 2018 The New York Botanical Garden All rights reserved ISBN 978-0-89327-955-4 Center for Conservation Strategy The New York Botanical Garden 2900 Southern Boulevard Bronx, NY 10458 All photos NYBG staff Citation: Atha, D. and B. Boom. 2018. State of New York City’s Plants 2018. Center for Conservation Strategy. The New York Botanical Garden, Bronx, NY. 132 pp. STATE OF NEW YORK CITY’S PLANTS 2018 4 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 6 INTRODUCTION 10 DOCUMENTING THE CITY’S PLANTS 10 The Flora of New York City 11 Rare Species 14 Focus on Specific Area 16 Botanical Spectacle: Summer Snow 18 CITIZEN SCIENCE 20 THREATS TO THE CITY’S PLANTS 24 NEW YORK STATE PROHIBITED AND REGULATED INVASIVE SPECIES FOUND IN NEW YORK CITY 26 LOOKING AHEAD 27 CONTRIBUTORS AND ACKNOWLEGMENTS 30 LITERATURE CITED 31 APPENDIX Checklist of the Spontaneous Vascular Plants of New York City 32 Ferns and Fern Allies 35 Gymnosperms 36 Nymphaeales and Magnoliids 37 Monocots 67 Dicots 3 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY This report, State of New York City’s Plants 2018, is the first rankings of rare, threatened, endangered, and extinct species of what is envisioned by the Center for Conservation Strategy known from New York City, and based on this compilation of The New York Botanical Garden as annual updates thirteen percent of the City’s flora is imperiled or extinct in New summarizing the status of the spontaneous plant species of the York City. five boroughs of New York City. This year’s report deals with the City’s vascular plants (ferns and fern allies, gymnosperms, We have begun the process of assessing conservation status and flowering plants), but in the future it is planned to phase in at the local level for all species. -

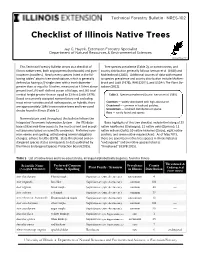

Checklist of Illinois Native Trees

Technical Forestry Bulletin · NRES-102 Checklist of Illinois Native Trees Jay C. Hayek, Extension Forestry Specialist Department of Natural Resources & Environmental Sciences Updated May 2019 This Technical Forestry Bulletin serves as a checklist of Tree species prevalence (Table 2), or commonness, and Illinois native trees, both angiosperms (hardwoods) and gym- county distribution generally follows Iverson et al. (1989) and nosperms (conifers). Nearly every species listed in the fol- Mohlenbrock (2002). Additional sources of data with respect lowing tables† attains tree-sized stature, which is generally to species prevalence and county distribution include Mohlen- defined as having a(i) single stem with a trunk diameter brock and Ladd (1978), INHS (2011), and USDA’s The Plant Da- greater than or equal to 3 inches, measured at 4.5 feet above tabase (2012). ground level, (ii) well-defined crown of foliage, and(iii) total vertical height greater than or equal to 13 feet (Little 1979). Table 2. Species prevalence (Source: Iverson et al. 1989). Based on currently accepted nomenclature and excluding most minor varieties and all nothospecies, or hybrids, there Common — widely distributed with high abundance. are approximately 184± known native trees and tree-sized Occasional — common in localized patches. shrubs found in Illinois (Table 1). Uncommon — localized distribution or sparse. Rare — rarely found and sparse. Nomenclature used throughout this bulletin follows the Integrated Taxonomic Information System —the ITIS data- Basic highlights of this tree checklist include the listing of 29 base utilizes real-time access to the most current and accept- native hawthorns (Crataegus), 21 native oaks (Quercus), 11 ed taxonomy based on scientific consensus. -

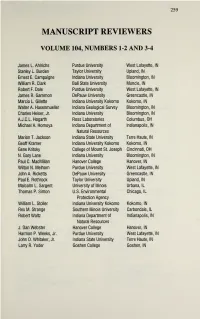

Proceedings of the Indiana Academy of Science 261 (1995) Volume 104 (3-4) P

259 MANUSCRIPT REVIEWERS VOLUME 104, NUMBERS 1-2 AND 3-4 James L. Ahlrichs Purdue University West Lafayette, IN Stanley L. Burden Taylor University Upland, IN Ernest E. Campaigne Indiana University Bloomington, IN William R. Clark Ball State University Muncie, IN Robert F. Dale Purdue University West Lafayette, IN James R. Gammon DePauw University Greencastle, IN Marcia L. Gillette Indiana University Kokomo Kokomo, IN Walter A. Hasenmueller Indiana Geological Survey Bloomington, IN Charles Heiser, Jr. Indiana University Bloomington, IN A.J.C.L. Hogarth Ross Laboratories Columbus, OH Michael A. Homoya Indiana Department of Indianapolis, IN Natural Resources Marion T. Jackson Indiana State University Terre Haute, IN Geoff Kramer Indiana University Kokomo Kokomo, IN Gene Kritsky College of Mount St. Joseph Cincinnati, OH N. Gary Lane Indiana University Bloomington, IN Paul C. MacMillan Hanover College Hanover, IN Wilton N. Melhorn Purdue University West Lafayette, IN John A. Ricketts DePauw University Greencastle, IN Paul E. Rothrock Taylor University Upland, IN Malcolm L. Sargent University of Illinois Urbana, IL Thomas P. Simon U.S. Environmental Chicago, IL Protection Agency William L. Stoller Indiana University Kokomo Kokomo, IN Rex M. Strange Southern Illinois University Carbondale, IL Robert Waltz Indiana Department of Indianapolis, IN Natural Resources J. Dan Webster Hanover College Hanover, IN Harmon P. Weeks, Jr. Purdue University West Lafayette, IN John 0. Whitaker, Jr. Indiana State University Terre Haute, IN Larry R. Yoder Goshen -

Acer Binzayedii (Sapindaceae), a New Maple Species from Mexico

Acer binzayedii (Sapindaceae), a new maple species from Mexico Yalma L. Vargas-Rodriguez, Lowell E. Urbatsch, Vesna Karaman-Castro & Blanca L. Figueroa-Rangel Brittonia ISSN 0007-196X Brittonia DOI 10.1007/s12228-017-9465-5 1 23 Your article is protected by copyright and all rights are held exclusively by The New York Botanical Garden. This e-offprint is for personal use only and shall not be self- archived in electronic repositories. If you wish to self-archive your article, please use the accepted manuscript version for posting on your own website. You may further deposit the accepted manuscript version in any repository, provided it is only made publicly available 12 months after official publication or later and provided acknowledgement is given to the original source of publication and a link is inserted to the published article on Springer's website. The link must be accompanied by the following text: "The final publication is available at link.springer.com”. 1 23 Author's personal copy Acer binzayedii (Sapindaceae), a new maple species from Mexico 1,2 1 1 YALMA L. VARGAS-RODRIGUEZ ,LOWELL E. URBATSCH ,VESNA KARAMAN-CASTRO , 3 AND BLANCA L. FIGUEROA-RANGEL 1 Department of Biological Sciences, Louisiana State University, 202 Life Sciences Building, Baton Rouge, LA 70803, USA; e-mail: [email protected] 2 National Council of Science and Technology, Av. Insurgentes Sur 1582, Col. Crédito Constructor, Ciudad de México, 03940 D.F., México 3 Department of Ecology and Natural Resources, Centro Universitario de la Costa Sur, Universidad de Guadalajara, Av. Independencia Nacional 151, 48900, Autlán de Navarro, Jalisco, México Abstract. -

For: March 31, 2018

Plant Lover’s Almanac Jim Chatfield Ohio State University Extension For: March 31, 2018 AcerMania. AcerPhilia. The crazy love of one of our greatest group of trees. Maples. From maple syrup to maple furniture. From musical instruments due to their tone-carrying trait to a wondrous range of landscape plants. Here are a few queries about maples I have received recently and a few rhetorical questions I have added to the mix for proper seasoning. Q. – Which maples are used to make maple syrup? A. – How topical. The obvious answer is sugar maple, Acer saccharum, with sweetness of the sap sewn into its Latin name. Silver maple is also sometimes used, and its Latin name, Acer saccharinum, suggests this is so. Black maple, Acer nigrum, is commonly used and it is so closely-related to sugar maple that it is often considered a sub-species. Box elder, Acer negundo, is also used somewhat in Canada, but to me one of the most surprisingly tapped maples, increasing in popularity in Ohio is red maple, Acer rubrum. Its sap is less sweet but red maple sugar-bushes are easier to manage. Q. Where does the name “Ácer” come from? A. The origins are somewhat obscure, but one theory is that its roots mean “sharp”, which if true would relate to the pointed nature of the leaf lobes on many maples. As a Latin genus name, Acer has over 120 species worldwide, with only one in the southern hemisphere. Q. – Which maples are native to the United States? A. - Five are familiar to us here in the northeastern U.S., namely sugar maple, red maple, silver maple, striped maple and box elder. -

Crataegus in Ohio with Description of One New Species

CRATAEGUS IN OHIO WITH DESCRIPTION OF ONE NEW SPECIES ERNEST J. PALMER Webb City, Missouri This review of Crataegus in Ohio has been made in cooperation with the Ohio Flora Committee of the Ohio Academy of Science as a contribution to their forth- coming flora of the state. Many of the universities and colleges of the state have sent collections of herbarium specimens to me for examination, and information has been drawn from these and other sources including some private collections. The large collection in the herbarium of the Ohio State University, covering most of the state, has been particularly helpful. Other institutions sending large col- lections were the University of Cincinnati, Oberlin College, Miami University, and Defiance College. Dr. E. Lucy Braun also sent many interesting collections from her private herbarium; and she has given invaluable assistance in outlining the work and in cooperating with it in many ways. In addition to the larger collections mentioned above, specimens have been received from Ohio University, Dennison University, Kent State University, Antioch College, and from the private collection of Mr. John Guccion of Cleveland. Dr. Gerald B. Ownbey also sent a number of collections from Ohio deposited in the herbarium of the University of Minnesota. The large amount of material from Ohio in the her- barium of the Arnold Arboretum, Jamaica Plain, Massachusetts, was also checked, including duplicates of many of the collections seen in Ohio herbaria, and also fuller collections made by R. E. Horsey in many parts of the state, and by F. J. Tyler, Harry Crowfoot, and C.