Reviews That Showed Foreign Films

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Oral History Interview with Massimo Vignelli, 2011 June 6-7

Oral history interview with Massimo Vignelli, 2011 June 6-7 Funding for this interview was provided by the Nanette L. Laitman Documentation Project for Craft and Decorative Arts in America. Contact Information Reference Department Archives of American Art Smithsonian Institution Washington. D.C. 20560 www.aaa.si.edu/askus Transcript Preface The following oral history transcript is the result of a tape-recorded interview with Massimo Vignelli on 2011 June 6-7. The interview took place at Vignelli's home and office in New York, NY, and was conducted by Mija Riedel for the Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. This interview is part of the Nanette L. Laitman Documentation Project for Craft and Decorative Arts in America. Mija Riedel has reviewed the transcript and have made corrections and emendations. This transcript has been lightly edited for readability by the Archives of American Art. The reader should bear in mind that they are reading a transcript of spoken, rather than written, prose. Interview MIJA RIEDEL: This is Mija Riedel with Massimo Vignelli in his New York City office on June 6, 2011, for the Smithsonian Archives of American Art. This is card number one. Good morning. Let's start with some of the early biographical information. We'll take care of that and move along. MASSIMO VIGNELLI: Okay. MIJA RIEDEL: You were born in Milan, in Italy, in 1931? MASSIMO VIGNELLI: Nineteen thirty-one, a long time ago. MIJA RIEDEL: Okay. What was the date? MASSIMO VIGNELLI: Actually, 80 years ago, January 10th. I'm a Capricorn. MIJA RIEDEL: January 10th. -

Designersresearch – Copy

GraphicGraphic DesignersDesigners ResearchResearch MASSIMO VIGNELLI Massimo received his ar- chitecture degree from the Politecnico di Milano. Married Lella Vignelli and together they created a small design studio: the Lella Unimark International was launched and Massimo Vignelli Office of Design in New York as Massimo Vignelli ex- and Architecture, Milan. panded his buisness. -US National Park Service -Saint Peter’s Church NY inte- rior (1977 ) Subway Map MTA NY City Transit Authority 1953 1960 1966 (1970) 1957 1965 (1967) 1971 American Airlines In this period, Vignelli attended the Moving to Chicago,US and School of Architecture and Universi- founding Unimark Interna- ty of Venice. tional. Vignelli resigned from UI and established his new corporation: Vignelli Asso- ciates. W I M C R O U W E L Crowel is a graphic design- er and typographer born in the Netherlands. In 1963 he founded the studio To- tal Design, now called To- tal Identity. His most well known work has been for the Stedelijk Museum. His typography is extremely well planned and based on very strict systems of grids. He has also designed ex- positions, album covers and identity systems. He has published two type- faces Fodor and Gridnik, digitized versions of both are available from The Foundry. S A B A U L S S Saul Bass was an American graph- He hand draws ic designer. He was most of his de- best known for his signs. He also design of motion Saul is best known makes anima- picture title se- for simple, geomet- tions. He uses quences, film, film ric shapes and their visual meta- posters, and clas- symbolism. -

Massimo Vignelli

Massimo Vignelli Alexander Fusté Studio I Fall 2014 Massimo Vignelli, born and raised in Italy, brought to America a new style of minimalist and grid based design. Massimo did so with his wife and business partner Lella Vignelli. He began designing professionally in 1950 and never stopped until he passed on May 23, 2014.1 He and his team created the faces of some of the most iconic and well known branding and designs in the world. Because their philosophy of design isn’t limited to just graphic design, they focused on many projects in many fields throughout their career. Because, to the Vignelli’s, “If you can’t find it, design it.”2 Massimo’s interest in Graphic Design began in Italy pre his marriage to Lella. It was here that he realized that he wanted to continue his life pursuing ‘good design’ in America with Lella. This idea of ‘good design’ was not simply limited to graphic design. Vignelli says in his book “Design is one” that “subjects change, materials change, processes change, but the creative and investigative mind proceeds relentlessly”.3 This process is applied to all created objects. After he arrived in America he cofounded Unimark and was the design director.4 This was a great starting point for Vignelli and gave him many opportunities. However, it was when he and Lella founded Vignelli Associates, did they really skyrocket to the design superstars they are today. 5 Massimo worked on a basic grid system throughout his the career. Why the grid? Because Massimo believed that good design is timeless and the grid will 1 AIGI. -

Kathy Brew in Conversation | Inspiration

Shop & Browse Inspiration In Conversation Kathy Brew Kathy Brew The Design Is One codirector talks behindthescenes with the Vignellis Kathy Brew found her way into film by way of a long career in media and contemporary art. After working in the Bay Area for fourteen years, Brew returned to her native New York in 1994 to begin work as an Associate Producer for “City Arts,” Channel 13’s Emmy-award-winning program on the visual and performing arts. While working on that series, Brew met her husband, Roberto Guerra, an accomplished filmmaker and longtime friend of the modernist designers Lella and Massimo Vignelli. In 2014, Roberto Guerra passed away on Massimo Vignelli’s birthday, January 10, after a six-month fight with pancreatic Photograph by Ana de Orbegoso cancer. Just months later, Massimo died at his home in Manhattan. He was 83. The last film that Brew made with her late husband, Design Is One: Lella & Massimo Vignelli, was created from footage that captures the Vignellis full of vim and verve, before health complications began to interfere with their ability to work. Along with Helvetica—a documentary film about Massimo Vignelli’s favorite typeface—Design Is One has helped catapult the Vignellis to a new level of public consciousness. After interviewing the Vignellis and former co-workers, Brew and Guerra compressed almost fifty years of work by the creative couple into the eighty-minute feature film, introducing many to the duo that helped shape America’s typographic urban landscape and the entire field of design in the latter half of the 20th century. -

Massimo Vignelli

6.0 | GERARCHIE FUNZIONALI | SCUOLA / DIPARTIMENTO / AMMINISTRAZIONE SCUOLA DI INGEGNERIA CIVILE, SCUOLA DI INGEGNERIA CIVILE, AMBIENTALE E TERRITORIALE AMBIENTALE E TERRITORIALE SCUOLA DI INGEGNERIA INDUSTRIALE SCUOLA DI INGEGNERIA INDUSTRIALE E DELL’INFORMAZIONE E DELL’INFORMAZIONE SCUOLA DI INGEGNERIA SCUOLA DI INGEGNERIA EDILE /ARCHITETTURA EDILE /ARCHITETTURA SCUOLA DI ARCHITETTURA SCUOLA DI ARCHITETTURA E SOCIETÀ E SOCIETÀ SCUOLA DI ARCHITETTURA CIVILE SCUOLA DI ARCHITETTURA CIVILE SCUOLA DI DESIGN SCUOLA DI DESIGN DesignVerso è una collana dedicata ai designer della comunicazione, immaginata come allegato alla rivista Multiverso, Università degli Studi di Udine. Comitato editoriale: Prof.ssa Daniela Calabi Prof.ssa Cristina Boeri Prof.ssa Raffaella Bruno Collaboratori e consulenti: Dott.ssa Monica Fumagalli Dott. Lorenzo Rabaioli Dott. Marco Valli Direttori editoriali: Fiorani Sara Gori Alessandro Magnelli Giulia Restifo Pilato Simone www.mvdesignverso.tk Design della Comunicazione C2, A.A. 2018/2019. Laboratorio di Fondamenti del Progetto EDITORIALE Attraverso questa monografia sono state esaminate l’ideologia e le influenze celate dietro al lavoro di Vignelli, rivelandone un’identità che rimarrà un riferimento nel corso degli anni, Per la sua increbile chiarezza e coerenza. Massimo Vignelli è molto di più delle sue opere, che nonostante siano di grandissima rilevanza, sono un punto di partenza per riassumere il suo pensiero e la sua identità: i suoi insegnamenti hanno tracciato una linea guida nel campo del design, alla quale designer emergenti e non possono ispirarsi per imparare i fondamentali della disciplina. Da questo deriva il taglio editoriale che si è deciso di adottare. Si è proposto Vignelli sotto una luce inusuale, diversa, insolita: vengono ripresi gli aspetti salienti della sua vita, dal fondamentale ruolo della moglie con la quale era in grande sintonia, al suo rigore, alla sua ben nota disciPlina, analizzando gli aspetti del movimento moderno del quale lui si erge come colonna portante. -

Ygb(I)V: Horizontal Color in the New York Subway

Robert R. Stenson Intro to Archaeology Joanna S. Smith 25 October 2007 R(o)ygb(i)v: Horizontal Color in the New York Subway The subway arrives in color. In our minds, our stations, and our maps, the New York City subway system arrives in colors: red, blue, orange, green, purple, etc. Whether you are holding a map, navigating the station, or standing on the platform, deciphering this subway means using color as a tool of instantaneous and conscious differentiation. That is, when we trace a line with our finger, spot a sign, or peer into the tunnel, we are consciously looking for a specific color, and can know instantaneously whether or not a train is “ours.” But the nature of this scheme is to operate in a “vertical” orientation. As we ride toward our destination, we ride with a color; as we glide north and south beneath the grey city, moving against the horizontal grid of cross-streets, the A train remains blue and the 1 remains red—no matter what station, either West 4th or 200th. But little-known in the New York subway complex is a limited, enigmatic system of “horizontal” color, bands of colored tile on station walls—a system which, theoretically, gives us the sense not of moving with a color, but through changing colors: green at West 4th, red at 200th etc. As a result of poor documentation and limited use, however, what we know of the colors is preserved primarily on the subway station walls; a once-modern scheme has silently become archaic, found only in an archaeological context. -

Poltrona-Frau-Icons.Pdf

Icone Poltrona Frau Icons Icona 5 ICONA ICON [i-cò-na] sostantivo femminile [i-con] noun 1) Effi gie sacra dipinta su tavola, propria 1) (Christianity / Eastern Church -Greek Icon dell’arte bizantina e poi russa e balcanica & Russian Orthodox) a representation of Christ, the Virgin 2) In semiologia, tipo di segno Mary, or a saint, esp one painted che riproduce una o più caratteristiche in oil on a wooden panel, depicted della realtà che denota in a traditional Byzantine style and venerated in the Eastern Church. 3) In informatica, immagine che rappresenta simbolicamente 2) A symbol resembling or analogous un programma, un comando o un fi le to the thing it represents. di dati: “trascinare l’icona” 3) (Electronic & Computer Science/ dal Sabatini Coletti, Computer Science) a pictorial Dizionario della Lingua Italiana representation of a facility available on a computer system, that enables the facility to be activated by means of a screen cursor rather than by a textual instruction: “drag the icon” from the Collins English Dictionary Complete and Unabridged L’icona è un’immagine sacra diff usa in tutto An icon is a sacred image spread throughout il mondo russo e balcanico fi n dalla più remota the world of Russia and the Balkans since ancient antichità. Tuttavia nel linguaggio contemporaneo times. However, in contemporary language, il termine “icona”, e soprattutto i suoi derivati the term ‘icon’, and above all the adjective deriving aggettivali “iconico” e “iconica”, sono entrati from it (‘iconic’), is now commonly used prepotentemente nell’uso corrente ad indicare to refer to some form of semantic absoluteness. -

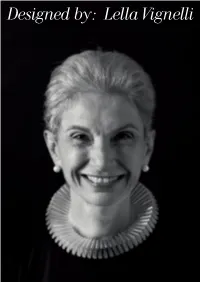

Designed By: Lella Vignelli

Designed by: Lella Vignelli Designed by: Lella Vignelli Acknowledgements This book is dedicated My most sincere appreciation to: to Lella Vignelli, Jan Conradi, with many thanks for an inspiration to all her patience and advice in reading and correcting my English. women designers who Mauro Sarri, who endured my forcefully stand on the continuous changes of the layouts and type to achieve this book design. power of their merits. New York, NY 2013 Massimo Vignelli Introduction For decades, the collaborative role of inspiration and incentive for young women in life and in the profession, should be based women as architects or designers working who are shaping their careers. Times are on mutual respect and appreciation for each with their husbands or partners has been changing… partner’s talent, sensibility, and culture. under appreciated. Fifty years ago, it was No partnership can exist, or last, without this standard practice that the head of the office The supporting role of the woman architect fundamental basis. was the man and the woman partner had has often been created by macho attitudes a subordinate role. At best, the woman’s of the male partner. Most of the glory went Lella and I have been partners, lovers, a creative input and professional influence to the men (not accidentally) while the married professional couple for more than was only vaguely accepted; often her women, as partner architects, found that half a century. From the beginning, our contributions were dismissed and sometimes their role was dismissed or totally ignored. relationship has been bonded by our mutual even forgotten. -

Addio a Massimo Vignelli, Pezzo Di Storia Del Design Italiano

Addio a Massimo Vignelli, pezzo di storia del design italiano È scomparso a New York, all’età di 83 anni, Massimo Vignelli, una tra le personalità di maggior rilievo del design italiano. Passato alla storia per il celebre slogan “Design is one”, con cui identificava che il design è “unico” e che se si è in grado di progettare una cosa, si può progettare tutto, Vignelli ha realizzato opere e lavori che sono rimasti impressi nella memoria collettiva, dai loghi di moltissime aziende mondiali fino a segnaletiche il cui potere iconico è ancora oggi immutato (come ad esempio quelle per le ferrovie italiane). Nato a Milano nel 1931, studia architettura al Politecnico e poi allo Iuav di Venezia. Il suo primo contatto con il product design avviene già da studente, collaborando alla realizzazione di alcune lampade in vetro soffiato per Venini. Fondamentale è l’incontro Elena Valle, al secolo Lella, con la quale avvia un legame professionale e personale, sposandola nel 1957. Nello stesso anno, grazie a un incarico temporaneo, si trasferisce con Lella negli Stati Uniti, facendo la spola con l’Italia per qualche anno. A Milano nel 1960 la coppia fonda il primo studio di design, operativo fino al trasferimento definitivo negli Usa, nel 1964. Qui partecipa all’avvio di “Unimark International”, studio di design internazionale e interdisciplinare, di cui è co- fondatore insieme a Ralph Eckerstrom, Bob Noorda, Jay Doblin, James Fogelman, Wally Gutches e Larry Klein. Vignelli lascia Unimark nel 1971 per fondare la Vignelli Associates, lo studio che ha attraversato la sua carriera fino ai giorni nostri. -

(Mostly) True Story of Helvetica and the New York City Subway by Paul Shaw November 18, 2008

FROM VOICE ~ TOPICS: branding/identity, history, signage, typography The (Mostly) True Story of Helvetica and the New York City Subway by Paul Shaw November 18, 2008 here is a commonly held belief that Helvetica is the signage typeface of the New York City subway system, a belief reinforced by Helvetica, Gary Hustwit’s popular 2007 documentary T about the typeface. But it is not true—or rather, it is only somewhat true. Helvetica is the official typeface of the MTA today, but it was not the typeface specified by Unimark International when it created a new signage system at the end of the 1960s. Why was Helvetica not chosen originally? What was chosen in its place? Why is Helvetica used now, and when did the changeover occur? To answer those questions this essay explores several important histories: of the New York City subway system, transportation signage in the 1960s, Unimark International and, of course, Helvetica. These four strands are woven together, over nine pages, to tell a story that ultimately transcends the simple issue of Helvetica and the subway. The Labyrinth As any New Yorker—or visitor to the city—knows, the subway system is a labyrinth. This is because it is an amalgamation of three separate systems, two of which incorporated earlier urban railway lines. The current New York subway system was formed in 1940 when the IRT (Interborough Rapid Transit), the BMT (Brooklyn-Manhattan Transit) and the IND (Independent) lines were merged. The IRT lines date to 1904; the BMT lines to 1908 (when it was the BRT, or Brooklyn Rapid Transit); and the IND to 1932. -

The Vignelli Legacy Published on Iitaly.Org (

Design is One: The Vignelli Legacy Published on iItaly.org (http://www.iitaly.org) Design is One: The Vignelli Legacy Emily Hayes (March 28, 2018) The Vignelli legacy is one that lives within the structure of New York City, and consists of simple, elegant designs that laid the basis for modernism in the United States. Massimo Vignelli and his partner Elena Valle (Lella) Vignelli conceived an iconic world of items, logos, and spaces for their international clients. Important pieces from their archive were open to the public at the Embassy of Italy in Washington, D.C. on March 16, for a lecture and exhibit opening entitled L’eredita’ dei Vignelli. The event was hosted by the Italian Cultural Institute, the Embassy of Italy, and the Rochester Institute of Technology. Photographs, sketches, book covers, maps, and brochures lined the walls of the exhibit, demonstrating the range of media and scope their work covered. New York City and Washington, D.C.’s iconic subway maps, Bloomingdale’s department store graphics, and the interior of St. Peter’s Church in Manhattan were just a few of the well-known designs the Vignelli’s created. Furniture, plate ware, clothes, jewelry, books on animal anatomy and brochures for the U.S. National Parks, all seemingly unconnected items, came together in the exhibit on Massimo [2] and Lella Vignelli [3]. Even the chairs and coffee table on the stage were Vignelli-designed. R. Roger Remington, Professor of Graphic Design from the Vignelli Center for Design at the Rochester Institute of Technology, spoke as a long-time friend during his lecture. -

Friends of the New York Transit Museum

Friends of the New York Transit Museum NYTM 2012 Annual Report Mission he mission of the New York Transit Museum is to collect, exhibit, interpret and preserve the history, sociology and technology of Tpublic transportation systems in the New York metropolitan region and to conduct research and educational programs that will make the Museum’s extensive collection accessible and meaningful to the broadest possible audience. 2012 Snap Shot ATTENDANCE 133,633 visitors to the Brooklyn location 133,633 390,762 visitors to Gallery Annex & Store at 12% increase Grand Central Terminal 119,167 1,063 Seniors admitted for Free Senior Wednesdays EDUCATION AND PUBLIC PROGRAMS 9,875 weekend workshop attendees 1,205 school and camp groups served (25,894 individuals) 151 special needs groups served 1,972 67 public programs and walking tours 8% increase 1,833 EXHIBITS AND ARCHIVES 7 exhibits installed 1,958 photographs cataloged and 72 objects photographed and cataloged 710 drawings, maps, posters, documents, ephemera cataloged 9,875 328 library books cataloged 18% increase 983 phone and email researchers 8,346 110 on-site researchers 47 donations and internal transfers 1 Artist Antonio Masi demonstrates his watercolor technique. Masi’s bridge paintings were featured in the exhibit, “New York’s Golden Age of Bridges.” From the Director n October 31st, 2012, two days Museum cemented its position as a resource after Hurricane Sandy slammed into and a leader in the special needs community. ONew York, the Transit Museum was Thanks to a $150,000 capacity-building grant one of the first cultural institutions in the from the Booth Ferris Foundation, the Mu- city to reopen, offering free admission and a seum created and filled the new position of much-needed distraction for families strug- finance director, marking an important step in gling to recover from the storm.