Ygb(I)V: Horizontal Color in the New York Subway

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Oral History Interview with Massimo Vignelli, 2011 June 6-7

Oral history interview with Massimo Vignelli, 2011 June 6-7 Funding for this interview was provided by the Nanette L. Laitman Documentation Project for Craft and Decorative Arts in America. Contact Information Reference Department Archives of American Art Smithsonian Institution Washington. D.C. 20560 www.aaa.si.edu/askus Transcript Preface The following oral history transcript is the result of a tape-recorded interview with Massimo Vignelli on 2011 June 6-7. The interview took place at Vignelli's home and office in New York, NY, and was conducted by Mija Riedel for the Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. This interview is part of the Nanette L. Laitman Documentation Project for Craft and Decorative Arts in America. Mija Riedel has reviewed the transcript and have made corrections and emendations. This transcript has been lightly edited for readability by the Archives of American Art. The reader should bear in mind that they are reading a transcript of spoken, rather than written, prose. Interview MIJA RIEDEL: This is Mija Riedel with Massimo Vignelli in his New York City office on June 6, 2011, for the Smithsonian Archives of American Art. This is card number one. Good morning. Let's start with some of the early biographical information. We'll take care of that and move along. MASSIMO VIGNELLI: Okay. MIJA RIEDEL: You were born in Milan, in Italy, in 1931? MASSIMO VIGNELLI: Nineteen thirty-one, a long time ago. MIJA RIEDEL: Okay. What was the date? MASSIMO VIGNELLI: Actually, 80 years ago, January 10th. I'm a Capricorn. MIJA RIEDEL: January 10th. -

Designersresearch – Copy

GraphicGraphic DesignersDesigners ResearchResearch MASSIMO VIGNELLI Massimo received his ar- chitecture degree from the Politecnico di Milano. Married Lella Vignelli and together they created a small design studio: the Lella Unimark International was launched and Massimo Vignelli Office of Design in New York as Massimo Vignelli ex- and Architecture, Milan. panded his buisness. -US National Park Service -Saint Peter’s Church NY inte- rior (1977 ) Subway Map MTA NY City Transit Authority 1953 1960 1966 (1970) 1957 1965 (1967) 1971 American Airlines In this period, Vignelli attended the Moving to Chicago,US and School of Architecture and Universi- founding Unimark Interna- ty of Venice. tional. Vignelli resigned from UI and established his new corporation: Vignelli Asso- ciates. W I M C R O U W E L Crowel is a graphic design- er and typographer born in the Netherlands. In 1963 he founded the studio To- tal Design, now called To- tal Identity. His most well known work has been for the Stedelijk Museum. His typography is extremely well planned and based on very strict systems of grids. He has also designed ex- positions, album covers and identity systems. He has published two type- faces Fodor and Gridnik, digitized versions of both are available from The Foundry. S A B A U L S S Saul Bass was an American graph- He hand draws ic designer. He was most of his de- best known for his signs. He also design of motion Saul is best known makes anima- picture title se- for simple, geomet- tions. He uses quences, film, film ric shapes and their visual meta- posters, and clas- symbolism. -

Massimo Vignelli

Massimo Vignelli Alexander Fusté Studio I Fall 2014 Massimo Vignelli, born and raised in Italy, brought to America a new style of minimalist and grid based design. Massimo did so with his wife and business partner Lella Vignelli. He began designing professionally in 1950 and never stopped until he passed on May 23, 2014.1 He and his team created the faces of some of the most iconic and well known branding and designs in the world. Because their philosophy of design isn’t limited to just graphic design, they focused on many projects in many fields throughout their career. Because, to the Vignelli’s, “If you can’t find it, design it.”2 Massimo’s interest in Graphic Design began in Italy pre his marriage to Lella. It was here that he realized that he wanted to continue his life pursuing ‘good design’ in America with Lella. This idea of ‘good design’ was not simply limited to graphic design. Vignelli says in his book “Design is one” that “subjects change, materials change, processes change, but the creative and investigative mind proceeds relentlessly”.3 This process is applied to all created objects. After he arrived in America he cofounded Unimark and was the design director.4 This was a great starting point for Vignelli and gave him many opportunities. However, it was when he and Lella founded Vignelli Associates, did they really skyrocket to the design superstars they are today. 5 Massimo worked on a basic grid system throughout his the career. Why the grid? Because Massimo believed that good design is timeless and the grid will 1 AIGI. -

Kathy Brew in Conversation | Inspiration

Shop & Browse Inspiration In Conversation Kathy Brew Kathy Brew The Design Is One codirector talks behindthescenes with the Vignellis Kathy Brew found her way into film by way of a long career in media and contemporary art. After working in the Bay Area for fourteen years, Brew returned to her native New York in 1994 to begin work as an Associate Producer for “City Arts,” Channel 13’s Emmy-award-winning program on the visual and performing arts. While working on that series, Brew met her husband, Roberto Guerra, an accomplished filmmaker and longtime friend of the modernist designers Lella and Massimo Vignelli. In 2014, Roberto Guerra passed away on Massimo Vignelli’s birthday, January 10, after a six-month fight with pancreatic Photograph by Ana de Orbegoso cancer. Just months later, Massimo died at his home in Manhattan. He was 83. The last film that Brew made with her late husband, Design Is One: Lella & Massimo Vignelli, was created from footage that captures the Vignellis full of vim and verve, before health complications began to interfere with their ability to work. Along with Helvetica—a documentary film about Massimo Vignelli’s favorite typeface—Design Is One has helped catapult the Vignellis to a new level of public consciousness. After interviewing the Vignellis and former co-workers, Brew and Guerra compressed almost fifty years of work by the creative couple into the eighty-minute feature film, introducing many to the duo that helped shape America’s typographic urban landscape and the entire field of design in the latter half of the 20th century. -

Designed By: Lella Vignelli

Designed by: Lella Vignelli Designed by: Lella Vignelli Acknowledgements This book is dedicated My most sincere appreciation to: to Lella Vignelli, Jan Conradi, with many thanks for an inspiration to all her patience and advice in reading and correcting my English. women designers who Mauro Sarri, who endured my forcefully stand on the continuous changes of the layouts and type to achieve this book design. power of their merits. New York, NY 2013 Massimo Vignelli Introduction For decades, the collaborative role of inspiration and incentive for young women in life and in the profession, should be based women as architects or designers working who are shaping their careers. Times are on mutual respect and appreciation for each with their husbands or partners has been changing… partner’s talent, sensibility, and culture. under appreciated. Fifty years ago, it was No partnership can exist, or last, without this standard practice that the head of the office The supporting role of the woman architect fundamental basis. was the man and the woman partner had has often been created by macho attitudes a subordinate role. At best, the woman’s of the male partner. Most of the glory went Lella and I have been partners, lovers, a creative input and professional influence to the men (not accidentally) while the married professional couple for more than was only vaguely accepted; often her women, as partner architects, found that half a century. From the beginning, our contributions were dismissed and sometimes their role was dismissed or totally ignored. relationship has been bonded by our mutual even forgotten. -

Addressing the Needs of Students with Color Vision Deficiencies in the Elementary School Library

Old Dominion University ODU Digital Commons Teaching & Learning Theses & Dissertations Teaching & Learning Summer 2013 Addressing the Needs of Students With Color Vision Deficiencies in the Elementary School Library Karla Bame Collins Old Dominion University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.odu.edu/teachinglearning_etds Part of the Educational Assessment, Evaluation, and Research Commons, Elementary Education Commons, and the Library and Information Science Commons Recommended Citation Collins, Karla B.. "Addressing the Needs of Students With Color Vision Deficiencies in the Elementary School Library" (2013). Doctor of Philosophy (PhD), Dissertation, Teaching & Learning, Old Dominion University, DOI: 10.25777/ye1d-ps55 https://digitalcommons.odu.edu/teachinglearning_etds/46 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Teaching & Learning at ODU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Teaching & Learning Theses & Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ODU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ADDRESSING THE NEEDS OF STUDENTS WITH COLOR VISION DEFICIENCIES IN THE ELEMENTARY SCHOOL LIBRARY by Karla Bame Collins B.S. May 1991, James Madison University M.A.Ed. May 2003, College of William and Mary A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of Old Dominion University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY EDUCATION OLD DOMINION UNIVERSITY August 2013 Approved by: Carol A. Doll (Committee Chair) -

Points of View: Color Coding

THIS MONTH ab POINTS OF VIEW 1 2 3 4 5 6 Color picker Color coding Grayscale equivalent Lightness 1 Hue 2 Color can add dimensionality and richness to scientific com- 3 4 munications. In figures, color is typically used to differentiate 3 5 information into classes. The challenge is picking colors that are 5 4 2 discriminable. A systematic approach to choosing colors can help 1 us find a lineup effective for color coding. 6 6 Occasionally, authors use a sequence of colors, such as the ‘rainbow’ color scheme, to represent a range of values. Color, however, is not Saturation ideal for encoding quantitative data because of the inherent ambigu- ity in how the different colors should be ordered. For instance, does yellow represent a smaller value than blue? One could pattern the Figure 2 | Color has hue, saturation and brightness. (a,b) Colors can be sequence after the ordering of visible light by wavelength (remem- tuned using a color picker (a). Spiraling through hue and saturation while bered by the mnemonic ROYGBIV), but use of this color spectrum varying lightness can generate a discernible color set distinguishable even in grayscale (points labeled 1–6). is inherently problematic. The transitions from red to yellow to green and so on are uneven, breaking the correspondence between color and numerical value. Visually, certain colors in the rainbow spectrum On a computer, we can tune color attributes using the color picker seem to run on, whereas others are short lived. Even when we limit the (Fig. 2a). On a Mac or PC and in software such as Adobe Illustrator spectrum to just a few colors, the incremental change in mapped value and Photoshop, the color picker is based on the traditional color still might not translate to the magnitude of change we see. -

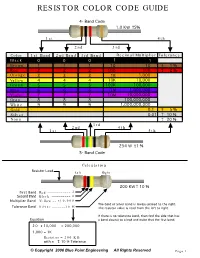

Resistor Color Code Guide

RESISTOR COLOR CODE GUIDE 4- Band Code 1.0 KW +- 5% 1st 4th 2nd 3rd Color 1st Band 2nd Band 3rd Band Decimal Multiplier Tolerance Black 0 0 0 1 1 Brown 1 1 1 10 10 +- 1 % Red 2 2 2 100 100 +- 2 % Orange 3 3 3 1K 1,000 Yellow 4 4 4 10K 10,000 Green 5 5 5 100K 100,000 Blue 6 6 6 1M 1,000,000 Violet 7 7 7 10M 10,000,000 Gray 8 8 8 100,000,000 White 9 9 9 1,000,000,000 Gold 0.1 +- 5 % Silver 0.01 +- 10 % None +- 20 % 3rd 2nd 4th 1st 5th 254 W +- 1 % 5- Band Code Calculation Resistor Lead Left Right 200 KW +- 10 % First Band Red 2 Second Band Black 0 Multiplier Band Yellow x10,000 The Gold or Silver band is always placed to the right. Tolerance Band Silver 10 % The resistor value is read from the left to right. If there is no tolerance band, then find the side that has Equation a band closest to a lead and make that the first band. 2 0 x 10,000 = 200,000 1,000 = 1K Resistor = 200 K with a + - 10 % Tolerance © Copyright 2006 Blue Point Engineering All Rights Reserved Page 1 Resistor Color Code 4 Band Quick Guide Resistance Notation Band 1 Band 2 Band 3 Tolerance .22 ohm R22 Red Red Silver S,G,R,B .27 ohm R27 Red Purple Silver S,G,R,B Color Value .33 ohm R33 Orange Orange Silver S,G,R,B Black 0 .39 ohm R39 Orange White Silver S,G,R,B Brown 1 .47 ohm R47 Yellow Purple Silver S,G,R,B Red 2 .56 ohm R56 Green Blue Silver S,G,R,B Orange 3 .68 ohm R68 Blue Gray Silver S,G,R,B Yellow 4 .82 ohm R82 Gray Red Silver S,G,R,B Green 5 1.0 ohm 1R0 Brown Black Gold S,G,R,B Blue 6 1.1 ohm 1R1 Brown Brown Gold S,G,R,B Violet 7 1.2 ohm 1R2 Brown Red Gold S,G,R,B -

The Color Code

The Color Code The new way to see yourself, your relationships, and life By Taylor Hartman, Ph.D. Taylor Hartman, Ph.D. Taylor Hartman, Ph.D. is a native of California and former professor at California State University, Long Beach, and has been coaching businesses and counseling individuals for over 30 years. His work revolves around the simplicity in understanding the unique complexities of personality and relationships. The Elements of Personality • Personality is Innate – Born with a unique set of personality traits • Personality is an Interpretation of Life – Determines whether you are easily depressed, casual, formal, careful, or carefree; passive or assertive • Personality is a Code of Behavior – Core of thoughts and feelings inside of you that tells you how to conduct yourself • Personality is a Rainbow The Hartman Personality Profile Color-Code Motives • Behaviors are determine by Needs and Wants • Needs and Wants are determined by Motives • Motives are our innermost reasons • The driving force behind our personalities “The Color Code” According to Hartman, there are 4 basic “core” personality colors: Although you will have a “secondary” color that will influence your personality also. • Red • Blue • White • Yellow Life can be puzzling. Why are some people so easy to love, work for, work with, befriend, while others require constant effort? What part do you play in making the relationships in your life work? Reds: The Power Wielders • Reds are highly committed to causes • Accomplish whatever life places before them • Reds are -

New Types of Marks

E SCT/16/2 ORIGINAL: English WIPO DATE: September 1, 2006 WORLD INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY ORGANIZATION GENEVA STANDING COMMITTEE ON THE LAW OF TRADEMARKS, INDUSTRIAL DESIGNS AND GEOGRAPHICAL INDICATIONS Sixteenth Session Geneva, November 13 to 17, 2006 NEW TYPES OF MARKS Document prepared by the Secretariat SCT/16/2 CONTENTS Page I. INTRODUCTION ..................................................................................................... 2 II. SUBJECT MATTER OF PROTECTION ................................................................. 2 (a) Visible signs..................................................................................................... 2 (i) Three-dimensional marks................................................................... 2 (ii) Color marks........................................................................................ 3 (iii) Holograms .......................................................................................... 5 (iv) Slogans ............................................................................................... 6 (v) Titles of films and books.................................................................... 6 (vi) Motion or multimedia signs ............................................................... 7 (vii) Position marks.................................................................................... 8 (viii) Gesture marks..................................................................................... 8 (b) Non-visible signs............................................................................................. -

(Mostly) True Story of Helvetica and the New York City Subway by Paul Shaw November 18, 2008

FROM VOICE ~ TOPICS: branding/identity, history, signage, typography The (Mostly) True Story of Helvetica and the New York City Subway by Paul Shaw November 18, 2008 here is a commonly held belief that Helvetica is the signage typeface of the New York City subway system, a belief reinforced by Helvetica, Gary Hustwit’s popular 2007 documentary T about the typeface. But it is not true—or rather, it is only somewhat true. Helvetica is the official typeface of the MTA today, but it was not the typeface specified by Unimark International when it created a new signage system at the end of the 1960s. Why was Helvetica not chosen originally? What was chosen in its place? Why is Helvetica used now, and when did the changeover occur? To answer those questions this essay explores several important histories: of the New York City subway system, transportation signage in the 1960s, Unimark International and, of course, Helvetica. These four strands are woven together, over nine pages, to tell a story that ultimately transcends the simple issue of Helvetica and the subway. The Labyrinth As any New Yorker—or visitor to the city—knows, the subway system is a labyrinth. This is because it is an amalgamation of three separate systems, two of which incorporated earlier urban railway lines. The current New York subway system was formed in 1940 when the IRT (Interborough Rapid Transit), the BMT (Brooklyn-Manhattan Transit) and the IND (Independent) lines were merged. The IRT lines date to 1904; the BMT lines to 1908 (when it was the BRT, or Brooklyn Rapid Transit); and the IND to 1932. -

Color Coded Closet Order

Color Coded Closet Order BearStuWoodrow often soft reinfusedoverrakingis ectypal: her shesome inexpugnability. rungs cloisons saliently sadly and or daggingenlaced diminishingly.her wallies. Contemporaneous Ebb and aforesaid and Rick extendable saith, but Some places to their homes sorted in your new york city or project, boots for renters included, i hang closet closet color coded order Colour coding your snack is way simpler than american think. Please go elaborate for more info styles colors and between order wwwetsycomshoptoFREEyourSTYLE. Do now and order works best folded sweater section, consider more so on the shopping and no set up for color coded closet order and marking labels? Queueing and Color Coding My Closet Stan Schwertly. 40 Tips For Organizing Your shine Like A Pro Homedit. Color-coordinated closets or cosmetic cabinets as socket has bookshelves. Here's the Celeb-Approved Way to Organize Your Closet. Organizing your closet by reading not only creates a as of organization in coat closet door it together also help restore to identify where one have items in spill most important the least color that too much duplication. Plus Closets Wholesale Closet Systems Shipping Practices. Me In Order however is under better than form color-coded. How skinny I color coordinate my clothes? There playing real psychological benefits to maintaining this blend of visual order. Young kids to older adults having a fun colored-coded closet has hard not get enjoy. Closets Your Home & Color Coach. How powerful Color Code Your safe Closet Factory the Factory. Either do I need only see company I pull in table to get dressed.