Addressing the Needs of Students with Color Vision Deficiencies in the Elementary School Library

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Blue Cone Monochromacy: Visual Function and Efficacy Outcome Measures for Clinical Trials

RESEARCH ARTICLE Blue Cone Monochromacy: Visual Function and Efficacy Outcome Measures for Clinical Trials Xunda Luo1☯‡, Artur V. Cideciyan1☯‡*, Alessandro Iannaccone2, Alejandro J. Roman1, Lauren C. Ditta2, Barbara J. Jennings2, Svetlana A. Yatsenko3, Rebecca Sheplock1, Alexander Sumaroka1, Malgorzata Swider1, Sharon B. Schwartz1, Bernd Wissinger4, Susanne Kohl4, Samuel G. Jacobson1* 1 Scheie Eye Institute, Department of Ophthalmology, Perelman School of Medicine, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, United States of America, 2 Hamilton Eye Institute, Department of Ophthalmology, University of Tennessee Health Science Center, Memphis, Tennessee, United States of America, 3 Pittsburgh Cytogenetics Laboratory, Center for Medical Genetics and Genomics, University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, United States of America, 4 Molecular Genetics Laboratory, Institute for Ophthalmic Research, Centre for Ophthalmology, University of Tuebingen, Tuebingen, Germany ☯ These authors contributed equally to this work. ‡ OPEN ACCESS These authors are joint first authors on this work. * [email protected] (SGJ); [email protected] (AVC) Citation: Luo X, Cideciyan AV, Iannaccone A, Roman AJ, Ditta LC, Jennings BJ, et al. (2015) Blue Cone Monochromacy: Visual Function and Efficacy Abstract Outcome Measures for Clinical Trials. PLoS ONE 10(4): e0125700. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0125700 Academic Editor: Dror Sharon, Hadassah-Hebrew University Medical Center, ISRAEL Background Blue Cone Monochromacy (BCM) is an X-linked retinopathy caused by mutations in the Received: December 29, 2014 OPN1LW / OPN1MW gene cluster, encoding long (L)- and middle (M)-wavelength sensitive Accepted: March 21, 2015 cone opsins. Recent evidence shows sufficient structural integrity of cone photoreceptors in Published: April 24, 2015 BCM to warrant consideration of a gene therapy approach to the disease. -

The Genetics of Normal and Defective Color Vision

Vision Research xxx (2011) xxx–xxx Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Vision Research journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/visres Review The genetics of normal and defective color vision Jay Neitz ⇑, Maureen Neitz University of Washington, Dept. of Ophthalmology, Seattle, WA 98195, United States article info a b s t r a c t Article history: The contributions of genetics research to the science of normal and defective color vision over the previ- Received 3 July 2010 ous few decades are reviewed emphasizing the developments in the 25 years since the last anniversary Received in revised form 25 November 2010 issue of Vision Research. Understanding of the biology underlying color vision has been vaulted forward Available online xxxx through the application of the tools of molecular genetics. For all their complexity, the biological pro- cesses responsible for color vision are more accessible than for many other neural systems. This is partly Keywords: because of the wealth of genetic variations that affect color perception, both within and across species, Color vision and because components of the color vision system lend themselves to genetic manipulation. Mutations Cone photoreceptor and rearrangements in the genes encoding the long, middle, and short wavelength sensitive cone pig- Colorblindness Cone mosaic ments are responsible for color vision deficiencies and mutations have been identified that affect the Opsin genes number of cone types, the absorption spectra of the pigments, the functionality and viability of the cones, Evolution and the topography of the cone mosaic. The addition of an opsin gene, as occurred in the evolution of pri- Comparative color vision mate color vision, and has been done in experimental animals can produce expanded color vision capac- Cone photopigments ities and this has provided insight into the underlying neural circuitry. -

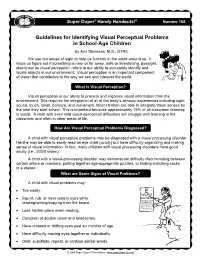

Visual Perceptual Skills

Super Duper® Handy Handouts!® Number 168 Guidelines for Identifying Visual Perceptual Problems in School-Age Children by Ann Stensaas, M.S., OTR/L We use our sense of sight to help us function in the world around us. It helps us figure out if something is near or far away, safe or threatening. Eyesight, also know as visual perception, refers to our ability to accurately identify and locate objects in our environment. Visual perception is an important component of vision that contributes to the way we see and interpret the world. What Is Visual Perception? Visual perception is our ability to process and organize visual information from the environment. This requires the integration of all of the body’s sensory experiences including sight, sound, touch, smell, balance, and movement. Most children are able to integrate these senses by the time they start school. This is important because approximately 75% of all classroom learning is visual. A child with even mild visual-perceptual difficulties will struggle with learning in the classroom and often in other areas of life. How Are Visual Perceptual Problems Diagnosed? A child with visual perceptual problems may be diagnosed with a visual processing disorder. He/she may be able to easily read an eye chart (acuity) but have difficulty organizing and making sense of visual information. In fact, many children with visual processing disorders have good acuity (i.e., 20/20 vision). A child with a visual-processing disorder may demonstrate difficulty discriminating between certain letters or numbers, putting together age-appropriate puzzles, or finding matching socks in a drawer. -

Metacognitive Awareness Inventory

Metacognitive Awareness Inventory What is Metacognition? The simplest definition of metacognition is “thinking about thinking.” This refers to the “self-regulation” effective learners exhibit, meaning they are aware of their learning process and can measure how efficiently they are learning as they study. Essentially, metacognition involves two simultaneous levels of thought: the first level is the student’s thinking/learning about the specific subject content and the second level is the student’s thinking about his/her learning. A student practicing metacognition would ask him/herself “How am I thinking?” or “Where am I in the learning process? Am I learning/understanding this topic? How could I learn more effectively?” These two levels are: knowledge and regulation. Students who are metacognitively aware demonstrate self-knowledge: They know what strategies and conditions work best for them while they are learning. Declarative, procedural, and conditional knowledge are essential for developing conceptual knowledge (content knowledge). Regulation refers to students’ knowledge about the implementation of strategies and the ability to monitor the effectiveness of their strategies. When students regulate, they are continually developing and monitoring their learning strategies based on their evolving self-knowledge. Complete the Metacognitive Awareness Inventory to assess your metacognitive processes. The Inventory Check True or False for each statement below. After you complete the inventory, use the scoring guide. Contact an Academic Coach at the Academic Support Center at (856) 681-6250 to discuss your results and strategies to increase your metacognitive awareness. True False 1. I ask myself periodically if I am meeting my goals. 2. I consider several alternatives to a problem before I answer. -

Will It Blend? Information Systems and Computer Engineering

Will It Blend? Studying Color Mixing Perception Paulo Duarte Esperanc¸a Garcia Thesis to obtain the Master of Science Degree in Information Systems and Computer Engineering Supervisors: Prof. Dr. Daniel Jorge Viegas Gonc¸alves Prof. Dra. Sandra Pereira Gama Examination Committee Chairperson: Prof. Dr. Antonio´ Manuel Ferreira Rito da Silva Supervisor: Prof. Dr. Daniel Jorge Viegas Gonc¸alves Member of the Committee: Prof. Dr. Manuel Joao˜ Caneira Monteiro da Fonseca November 2016 Acknowledgments First, I want to thank my advisor Professor Daniel Gonc¸alves for his excellent guidance, for always having the availability to teach, help and clarify, for his enormous knowledge and expertise, and for al- ways believing in the best result possible of this Master Thesis. Then, I also want to thank my co-advisor Sandra Gama, for her more-than-valuable inputs on Information Visualization and for opening the path for this dissertation and others to come! Additionally, I would like to thank everyone which somehow contributed for this thesis to happen: everyone who participated either online, or on the laboratory sessions, specially those who did it so willingly, without looking at the rewards. Without them, there would be no validity is this thesis. I must express my very profound gratitude to my family, particularly my mother Ondina and brother Diogo, for providing me with unfailing support and continuous encouragement throughout my years of study and through the process of researching and writing this thesis. This accomplishment would not have been possible without them. Thank you! Finally, to my girlfriend Margarida, my beloved partner, my shelter and support, for all the sleepless nights, sweat and tears throughout the last seven years. -

Structure of Cone Photoreceptors

Progress in Retinal and Eye Research 28 (2009) 289–302 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Progress in Retinal and Eye Research journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/prer Structure of cone photoreceptors Debarshi Mustafi a, Andreas H. Engel a,b, Krzysztof Palczewski a,* a Department of Pharmacology, Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland, OH 44106-4965, USA b Center for Cellular Imaging and Nanoanalytics, M.E. Mu¨ller Institute, Biozentrum, WRO-1058, Mattenstrasse 26, CH 4058 Basel, Switzerland abstract Keywords: Although outnumbered more than 20:1 by rod photoreceptors, cone cells in the human retina mediate Cone photoreceptors daylight vision and are critical for visual acuity and color discrimination. A variety of human diseases are Rod photoreceptors characterized by a progressive loss of cone photoreceptors but the low abundance of cones and the Retinoids absence of a macula in non-primate mammalian retinas have made it difficult to investigate cones Retinoid cycle directly. Conventional rodents (laboratory mice and rats) are nocturnal rod-dominated species with few Chromophore Opsins cones in the retina, and studying other animals with cone-rich retinas presents various logistic and Retina technical difficulties. Originating in the early 1900s, past research has begun to provide insights into cone Vision ultrastructure but has yet to afford an overall perspective of cone cell organization. This review Rhodopsin summarizes our past progress and focuses on the recent introduction of special mammalian models Cone pigments (transgenic mice and diurnal rats rich in cones) that together with new investigative techniques such as Enhanced S-cone syndrome atomic force microscopy and cryo-electron tomography promise to reveal a more unified concept of cone Retinitis pigmentosa photoreceptor organization and its role in retinal diseases. -

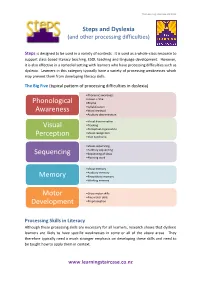

Phonological Awareness Visual Perception Sequencing Memory

The Learning Staircase Ltd 2012 Steps and Dyslexia (and other processing difficulties) Steps is designed to be used in a variety of contexts. It is used as a whole-class resource to support class-based literacy teaching, ESOL teaching and language development. However, it is also effective in a remedial setting with learners who have processing difficulties such as dyslexia. Learners in this category typically have a variety of processing weaknesses which may prevent them from developing literacy skills. The Big Five (typical pattern of processing difficulties in dyslexia) •Phonemic awareness •Onset + rime Phonological •Rhyme •Syllabification Awareness •Word retrieval •Auditory discrimination •Visual discrimination Visual •Tracking •Perceptual organisation •Visual recognition Perception •Irlen Syndrome •Visual sequencing •Auditory sequencing Sequencing •Sequencing of ideas •Planning work •Visual memory •Auditory memory Memory •Kinaesthetic memory •Working memory Motor •Gross motor skills •Fine motor skills Development •Proprioception Processing Skills in Literacy Although these processing skills are necessary for all learners, research shows that dyslexic learners are likely to have specific weaknesses in some or all of the above areas. They therefore typically need a much stronger emphasis on developing these skills and need to be taught how to apply them in context. www.learningstaircase.co.nz The Learning Staircase Ltd 2012 However, there are further aspects which are important, particularly for learners with literacy difficulties, such as dyslexia. These learners often need significantly more reinforcement. Research shows that a non-dyslexic learner needs typically between 4 – 10 exposures to a word to fix it in long-term memory. A dyslexic learner, on the other hand, can need 500 – 1300 exposures to the same word. -

The Genetic Horizon Improving Clinical Sensitivity in Difficult-To-Sequence Genes for Rare Hereditary Disorders

White paper The Genetic Horizon Improving clinical sensitivity in difficult-to-sequence genes for rare hereditary disorders Meeting clinical needs using custom solutions From Bench to Bedside: The Genetic Horizon Ongoing challenges The long-awaited promise of tailored treatments for individual patients based on their genetic Clinically relevant but highly homologous and · Masked regions in the reference data sets contain makeup is beginning to materialize. Next generation sequencing, along with artificial intelligence, repetitive regions within important genes are an uncertain or ambiguous variant calls that are the source ongoing challenge to analyze: of false positives, false negatives and other genotype have facilitated the rapid, accurate analysis and interpretation of genomic data for disease causing calling errors (e.g., calling homozygous variant at a variants which may be treatable through emerging gene therapy technology. · Certain genomic regions are difficult to analyze due to heterozygous site)1. complex sequence variations therein The number of clinical trials and drug development involves delivering a functional copy of the SMN1 gene in a Blueprint Genetics remains committed to resolving pipelines for rare disease are quickly growing and, one-time intravenous infusion (www.avexis.com). · Not only are there variants in these regions but there difficult-to-sequence regions that are hard to validate, encouragingly, the first approved treatments have been are types of variants that we cannot detect in the clinical interpret and confirm, by developing custom solutions. In successful. As the field of precision medicine is still in its The power of gene therapies is in the specificity of the diagnostic laboratory with current technologies (Table 1) this paper, we share our strategies and what is next in our infancy, increased awareness about the clinical utility of treatments: understanding the genetic mechanism of R&D pipeline. -

Intermixing the OPN1LW and OPN1MW Genes Disrupts the Exonic Splicing Code Causing an Array of Vision Disorders

G C A T T A C G G C A T genes Review Intermixing the OPN1LW and OPN1MW Genes Disrupts the Exonic Splicing Code Causing an Array of Vision Disorders Maureen Neitz * and Jay Neitz Department of Ophthalmology and Vision Science Center, University of Washington, Seattle, WA 98109, USA; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +1-206-543-7998 Abstract: Light absorption by photopigment molecules expressed in the photoreceptors in the retina is the first step in seeing. Two types of photoreceptors in the human retina are responsible for image formation: rods, and cones. Except at very low light levels when rods are active, all vision is based on cones. Cones mediate high acuity vision and color vision. Furthermore, they are critically important in the visual feedback mechanism that regulates refractive development of the eye during childhood. The human retina contains a mosaic of three cone types, short-wavelength (S), long-wavelength (L), and middle-wavelength (M) sensitive; however, the vast majority (~94%) are L and M cones. The OPN1LW and OPN1MW genes, located on the X-chromosome at Xq28, encode the protein component of the light-sensitive photopigments expressed in the L and M cones. Diverse haplotypes of exon 3 of the OPN1LW and OPN1MW genes arose thru unequal recombination mechanisms that have intermixed the genes. A subset of the haplotypes causes exon 3- skipping during pre-messenger RNA splicing and are associated with vision disorders. Here, we review the mechanism by which splicing defects in these genes cause vision disorders. Citation: Neitz, M.; Neitz, J. -

The Natural Power of Intuition

THE NATURAL POWER OF INTUITION: EXPLORING THE FORMATIVE DIMENSIONS OF INTUITION IN THE PRACTICES OF THREE VISUAL ARTISTS AND THREE BUSINESS EXECUTIVES by Jessica Jagtiani Dissertation Committee: Professor Judith Burton, Sponsor Professor Mary Hafeli Approved by the Committee on the Degree of Doctor of Education Date 16 May 2018 Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Education in Teachers College, Columbia University 2018 ABSTRACT THE NATURAL POWER OF INTUITION: EXPLORING THE FORMATIVE DIMENSIONS OF INTUITION IN THE PRACTICES OF THREE VISUAL ARTISTS AND THREE BUSINESS EXECUTIVES Jessica Jagtiani Both artists and business executives state the importance of intuition in their professional practice. Current research suggests that intuition plays a significant role in cognition, decision-making, and creativity. Intuitive perception is beneficial to management, entrepreneurship, learning, medical diagnosis, healing, spiritual growth, and overall well-being, and is furthermore, more accurate than deliberative thought under complex conditions. Accordingly, acquiring intuitive faculties seems indispensable amid present day’s fast-paced multifaceted society and growing complexity. Today, there is an overall rising interest in intuition and an existing pool of research on intuition in management, but interestingly an absence of research on intuition in the field of art. This qualitative-phenomenological study explores the experience of intuition in both professional practices in order to show comparability and extend the base of intuition, while at the same time revealing what is unique about its emergence in art practice. Data gathered from semi-structured interviews and online-journals provided the participants’ experience of intuition and are presented through individual portraits, including an introduction to their work, their worldview, and the experiences of intuition in their lives and professional practice. -

Progressive Cone and Cone-Rod Dystrophies

Br J Ophthalmol: first published as 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2018-313278 on 24 January 2019. Downloaded from Review Progressive cone and cone-rod dystrophies: clinical features, molecular genetics and prospects for therapy Jasdeep S Gill,1 Michalis Georgiou,1,2 Angelos Kalitzeos,1,2 Anthony T Moore,1,3 Michel Michaelides1,2 ► Additional material is ABSTRact proteins involved in photoreceptor structure, or the published online only. To view Progressive cone and cone-rod dystrophies are a clinically phototransduction cascade. please visit the journal online (http:// dx. doi. org/ 10. 1136/ and genetically heterogeneous group of inherited bjophthalmol- 2018- 313278). retinal diseases characterised by cone photoreceptor PHOTORECEPTION AND THE degeneration, which may be followed by subsequent 1 PHOTOTRANSDUCTION CASCADE UCL Institute of rod photoreceptor loss. These disorders typically present Rod photoreceptors contain rhodopsin phot- Ophthalmology, University with progressive loss of central vision, colour vision College London, London, UK opigment, whereas cone photoreceptors contain 2Moorfields Eye Hospital NHS disturbance and photophobia. Considerable progress one of three types of opsin: S-cone, M-cone or Foundation Trust, London, UK has been made in elucidating the molecular genetics L-cone opsin. Disease-causing sequence variants 3 Ophthalmology Department, and genotype–phenotype correlations associated with in the genes encoding the latter two cone opsins University of California San these dystrophies, with mutations in at least 30 genes -

The Mindful Attention Awareness Scale (MAAS)

The Mindful Attention Awareness Scale (MAAS) The trait MAAS is a 15-item scale designed to assess a core characteristic of mindfulness, namely, a receptive state of mind in which attention, informed by a sensitive awareness of what is occurring in the present, simply observes what is taking place. Brown, K.W. & Ryan, R.M. (2003). The benefits of being present: Mindfulness and its role in psychological well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 84, 822-848. Carlson, L.E. & Brown, K.W. (2005). Validation of the Mindful Attention Awareness Scale in a cancer population. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 58, 29-33. Instructions: Below is a collection of statements about your everyday experience. Using the 1-6 scale below, please indicate how frequently or infrequently you currently have each experience. Please answer according to what really reflects your experience rather than what you think your experience should be. Please treat each item separately from every other item. 1 2 3 4 5 6 almost very somewhat somewhat very almost never always frequently frequently infrequently infrequently _____ 1. I could be experiencing some emotion and not be conscious of it until some time later. _____ 2. I break or spill things because of carelessness, not paying attention, or thinking of something else. _____ 3. I find it difficult to stay focused on what’s happening in the present. _____ 4. I tend to walk quickly to get where I’m going without paying attention to what I experience along the way. _____ 5. I tend not to notice feelings of physical tension or discomfort until they really grab my attention.