Attention Awareness and Noticing Revised JW

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Impact of Pushed Output on Accuracy and Fluency Of

Iranian Journal of Language Teaching Research 2(2), (July, 2014) 51-72 51 Content list available at www.urmia.ac.ir/ijltr Urmia University The impact of pushed output on accuracy and fluency of Iranian EFL learners’ speaking Aram Reza Sadeghi Beniss a, Vahid Edalati Bazzaz a, * a Semnan University, Iran A B S T R A C T The current study attempted to establish baseline quantitative data on the impacts of pushed output on two components of speaking (i.e., accuracy and fluency). To achieve this purpose, 30 female EFL learners were selected from a whole population pool of 50 based on the standard test of IELTS interview and were randomly assigned into an experimental group and a control group. The participants in the experimental group received pushed output treatment while the students in the control group received non-pushed output instruction. The data were collected through IELTS interview and then the interview of each participant was separately tape-recorded and later transcribed and coded to measure accuracy and fluency. Then, the independent samples t-test was employed to analyze the collected data. The results revealed that the experimental group outperformed the control group in accuracy. In contrast, findings substantiated that pushed output had no impact on fluency. The positive impact of pushed output demonstrated in this study is consistent with the hypothesized function of Swain’s (1985) pushed output. The results can provide some useful insights into syllabus design and English language teaching. Keywords: pushed output; accuracy; fluency; EFL speaking © Urmia University Press A R T I C L E S U M M A R Y Received: 28 Jan. -

The Impact of Task Complexity on the Development of L2 Grammar

English Teaching, Vol. 75, No. 1, Spring 2020, pp. 93-117 DOI: https://doi.org/10.15858/engtea.75.1.202003.93 http://journal.kate.or.kr The Impact of Task Complexity on the Development of L2 Grammar Ji-Yung Jung* Jung, Ji-Yung. (2020). The impact of task complexity on the development of L2 grammar. English Teaching, 75(1), 93-117. The Cognition Hypothesis postulates that more cognitively complex tasks can trigger more accurate and complex language production, thereby advancing second language (L2) development. However, few studies have directly examined the relationship between task manipulations and L2 development. To address this gap, this article reviews, via an analytic approach, nine empirical studies that investigated the impact of task complexity on L2 development in the domain of morphosyntax. The studies are categorized into two groups based on if they include learner-learner interaction or a focus on form (FonF) treatment provided by an expert interlocutor. The results indicate that the findings of the studies, albeit partially mixed, tend to support the predictions of the Cognition Hypothesis. More importantly, a further analysis reveals seven key methodological issues that need to be considered in future research: target linguistic domains, different types of FonF, the complexity of the target structure, task types, outcome measures, the use of introspective methods, and the need of more empirical studies and replicable study designs. Key words: task complexity, Cognition Hypothesis, resource-directing and resource-dispersing -

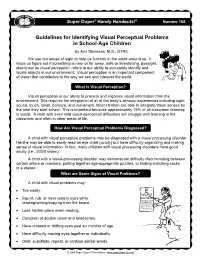

Visual Perceptual Skills

Super Duper® Handy Handouts!® Number 168 Guidelines for Identifying Visual Perceptual Problems in School-Age Children by Ann Stensaas, M.S., OTR/L We use our sense of sight to help us function in the world around us. It helps us figure out if something is near or far away, safe or threatening. Eyesight, also know as visual perception, refers to our ability to accurately identify and locate objects in our environment. Visual perception is an important component of vision that contributes to the way we see and interpret the world. What Is Visual Perception? Visual perception is our ability to process and organize visual information from the environment. This requires the integration of all of the body’s sensory experiences including sight, sound, touch, smell, balance, and movement. Most children are able to integrate these senses by the time they start school. This is important because approximately 75% of all classroom learning is visual. A child with even mild visual-perceptual difficulties will struggle with learning in the classroom and often in other areas of life. How Are Visual Perceptual Problems Diagnosed? A child with visual perceptual problems may be diagnosed with a visual processing disorder. He/she may be able to easily read an eye chart (acuity) but have difficulty organizing and making sense of visual information. In fact, many children with visual processing disorders have good acuity (i.e., 20/20 vision). A child with a visual-processing disorder may demonstrate difficulty discriminating between certain letters or numbers, putting together age-appropriate puzzles, or finding matching socks in a drawer. -

Metacognitive Awareness Inventory

Metacognitive Awareness Inventory What is Metacognition? The simplest definition of metacognition is “thinking about thinking.” This refers to the “self-regulation” effective learners exhibit, meaning they are aware of their learning process and can measure how efficiently they are learning as they study. Essentially, metacognition involves two simultaneous levels of thought: the first level is the student’s thinking/learning about the specific subject content and the second level is the student’s thinking about his/her learning. A student practicing metacognition would ask him/herself “How am I thinking?” or “Where am I in the learning process? Am I learning/understanding this topic? How could I learn more effectively?” These two levels are: knowledge and regulation. Students who are metacognitively aware demonstrate self-knowledge: They know what strategies and conditions work best for them while they are learning. Declarative, procedural, and conditional knowledge are essential for developing conceptual knowledge (content knowledge). Regulation refers to students’ knowledge about the implementation of strategies and the ability to monitor the effectiveness of their strategies. When students regulate, they are continually developing and monitoring their learning strategies based on their evolving self-knowledge. Complete the Metacognitive Awareness Inventory to assess your metacognitive processes. The Inventory Check True or False for each statement below. After you complete the inventory, use the scoring guide. Contact an Academic Coach at the Academic Support Center at (856) 681-6250 to discuss your results and strategies to increase your metacognitive awareness. True False 1. I ask myself periodically if I am meeting my goals. 2. I consider several alternatives to a problem before I answer. -

Ian Davison Supervisor: Dr. Jenefer Philp Phd in Applied Linguistics By

Department of Linguistics and English Language Student: Ian Davison Supervisor: Dr. Jenefer Philp PhD in Applied Linguistics by Thesis and Coursework Thesis submitted for PhD in Applied Linguistics “The Effects of Carrying out Collaborative Writing on the Individual Writing Proficiency of English Second Language Learners in an English for Academic Purposes Program” Abstract This quasi-experimental classroom-based study (n=128) looks at what students in an English for Academic Purposes Program (EAP) learn from the process of writing collaboratively and how this affects the individual writing that they subsequently produce. This is compared to how individual writing is affected by carrying out independent writing. Previous research carried out by Storch (2005), Storch and Wigglesworth (2007), Wigglesworth and Storch (2009), Dobao (2012), McDonough, De Vleeschauwer and Crawford (2018) and Villarreal and Gil-Sarratea (2019) found that writing produced collaboratively (by pairs or groups of writers) was more accurate than writing produced independently. This thesis suggests that individual students can learn from the process of writing collaboratively and that their own subsequent individual writing could become more accurate or improve as a result. Analysis of individual pre and post-test writing completed before and after two groups of students had carried out a series of writing tasks either collaboratively (collaborative writing group, n=64) or independently (independent writing group, n=64) over a period of 8 weeks revealed that accuracy increased to a significantly greater degree in the post-test writing of students from the collaborative group than in the same writing of students from the independent writing group. On the other hand, there were similar statistically significant increases in fluency and lexical complexity in the post-test writing of both groups and in the coherence and cohesion of post-test writing although syntactic complexity did not increase significantly in either group. -

Learner Differences in Metalinguistic Awareness: Exploring the Influence of Cognitive Abilities and Language Experience

Learner Differences in Metalinguistic Awareness: Exploring the Influence of Cognitive Abilities and Language Experience Daniel O. Jackson University of Hawai‘i at M ānoa 1. Introduction Recent emergentist views of language propose that its structure is “fundamentally molded by preexisting cognitive abilities, processing idiosyncrasies, and limitations” (Beckner et al., 2009, p. 17). Thus, the psychological characteristics that distinguish us as human contribute to language change at the collective and individual levels. With regard to the latter, it is particularly important for second language professionals to understand the nature of learners’ individual differences (IDs), so that we may appreciate these abilities, adapt instruction to idiosyncrasies, and circumvent limitations to the greatest extent possible. The outlook for research on IDs extends this perspective. For example, Dörnyei (2009) views IDs in second language (L2) research as multi-componential, integrated, dynamic, interacting, and complex. These themes are touched on throughout the following paper, which examines the role of L2 aptitude, working memory, and language experience in metalinguistic awareness stemming from exposure to an artificial language. * 2. Demystifying awareness for L2 research Following Schmidt (1990 and elsewhere), awareness is a form of consciousness implicated in mental processes that are crucial to L2 learning, including perception, noticing, and understanding. Regarding the distinction between noticing and understanding, he wrote: Noticing is related to rehearsal within working memory and the transfer of information to long- term memory, to intake, and to item learning. Understanding is related to the organization of material in long-term memory, to restructuring, and to system learning. (Schmidt, 1993, p. 213) Second language acquisition relies on both item and system learning. -

Will It Blend? Information Systems and Computer Engineering

Will It Blend? Studying Color Mixing Perception Paulo Duarte Esperanc¸a Garcia Thesis to obtain the Master of Science Degree in Information Systems and Computer Engineering Supervisors: Prof. Dr. Daniel Jorge Viegas Gonc¸alves Prof. Dra. Sandra Pereira Gama Examination Committee Chairperson: Prof. Dr. Antonio´ Manuel Ferreira Rito da Silva Supervisor: Prof. Dr. Daniel Jorge Viegas Gonc¸alves Member of the Committee: Prof. Dr. Manuel Joao˜ Caneira Monteiro da Fonseca November 2016 Acknowledgments First, I want to thank my advisor Professor Daniel Gonc¸alves for his excellent guidance, for always having the availability to teach, help and clarify, for his enormous knowledge and expertise, and for al- ways believing in the best result possible of this Master Thesis. Then, I also want to thank my co-advisor Sandra Gama, for her more-than-valuable inputs on Information Visualization and for opening the path for this dissertation and others to come! Additionally, I would like to thank everyone which somehow contributed for this thesis to happen: everyone who participated either online, or on the laboratory sessions, specially those who did it so willingly, without looking at the rewards. Without them, there would be no validity is this thesis. I must express my very profound gratitude to my family, particularly my mother Ondina and brother Diogo, for providing me with unfailing support and continuous encouragement throughout my years of study and through the process of researching and writing this thesis. This accomplishment would not have been possible without them. Thank you! Finally, to my girlfriend Margarida, my beloved partner, my shelter and support, for all the sleepless nights, sweat and tears throughout the last seven years. -

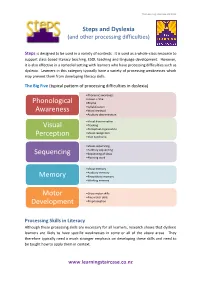

Phonological Awareness Visual Perception Sequencing Memory

The Learning Staircase Ltd 2012 Steps and Dyslexia (and other processing difficulties) Steps is designed to be used in a variety of contexts. It is used as a whole-class resource to support class-based literacy teaching, ESOL teaching and language development. However, it is also effective in a remedial setting with learners who have processing difficulties such as dyslexia. Learners in this category typically have a variety of processing weaknesses which may prevent them from developing literacy skills. The Big Five (typical pattern of processing difficulties in dyslexia) •Phonemic awareness •Onset + rime Phonological •Rhyme •Syllabification Awareness •Word retrieval •Auditory discrimination •Visual discrimination Visual •Tracking •Perceptual organisation •Visual recognition Perception •Irlen Syndrome •Visual sequencing •Auditory sequencing Sequencing •Sequencing of ideas •Planning work •Visual memory •Auditory memory Memory •Kinaesthetic memory •Working memory Motor •Gross motor skills •Fine motor skills Development •Proprioception Processing Skills in Literacy Although these processing skills are necessary for all learners, research shows that dyslexic learners are likely to have specific weaknesses in some or all of the above areas. They therefore typically need a much stronger emphasis on developing these skills and need to be taught how to apply them in context. www.learningstaircase.co.nz The Learning Staircase Ltd 2012 However, there are further aspects which are important, particularly for learners with literacy difficulties, such as dyslexia. These learners often need significantly more reinforcement. Research shows that a non-dyslexic learner needs typically between 4 – 10 exposures to a word to fix it in long-term memory. A dyslexic learner, on the other hand, can need 500 – 1300 exposures to the same word. -

The Natural Power of Intuition

THE NATURAL POWER OF INTUITION: EXPLORING THE FORMATIVE DIMENSIONS OF INTUITION IN THE PRACTICES OF THREE VISUAL ARTISTS AND THREE BUSINESS EXECUTIVES by Jessica Jagtiani Dissertation Committee: Professor Judith Burton, Sponsor Professor Mary Hafeli Approved by the Committee on the Degree of Doctor of Education Date 16 May 2018 Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Education in Teachers College, Columbia University 2018 ABSTRACT THE NATURAL POWER OF INTUITION: EXPLORING THE FORMATIVE DIMENSIONS OF INTUITION IN THE PRACTICES OF THREE VISUAL ARTISTS AND THREE BUSINESS EXECUTIVES Jessica Jagtiani Both artists and business executives state the importance of intuition in their professional practice. Current research suggests that intuition plays a significant role in cognition, decision-making, and creativity. Intuitive perception is beneficial to management, entrepreneurship, learning, medical diagnosis, healing, spiritual growth, and overall well-being, and is furthermore, more accurate than deliberative thought under complex conditions. Accordingly, acquiring intuitive faculties seems indispensable amid present day’s fast-paced multifaceted society and growing complexity. Today, there is an overall rising interest in intuition and an existing pool of research on intuition in management, but interestingly an absence of research on intuition in the field of art. This qualitative-phenomenological study explores the experience of intuition in both professional practices in order to show comparability and extend the base of intuition, while at the same time revealing what is unique about its emergence in art practice. Data gathered from semi-structured interviews and online-journals provided the participants’ experience of intuition and are presented through individual portraits, including an introduction to their work, their worldview, and the experiences of intuition in their lives and professional practice. -

The Mindful Attention Awareness Scale (MAAS)

The Mindful Attention Awareness Scale (MAAS) The trait MAAS is a 15-item scale designed to assess a core characteristic of mindfulness, namely, a receptive state of mind in which attention, informed by a sensitive awareness of what is occurring in the present, simply observes what is taking place. Brown, K.W. & Ryan, R.M. (2003). The benefits of being present: Mindfulness and its role in psychological well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 84, 822-848. Carlson, L.E. & Brown, K.W. (2005). Validation of the Mindful Attention Awareness Scale in a cancer population. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 58, 29-33. Instructions: Below is a collection of statements about your everyday experience. Using the 1-6 scale below, please indicate how frequently or infrequently you currently have each experience. Please answer according to what really reflects your experience rather than what you think your experience should be. Please treat each item separately from every other item. 1 2 3 4 5 6 almost very somewhat somewhat very almost never always frequently frequently infrequently infrequently _____ 1. I could be experiencing some emotion and not be conscious of it until some time later. _____ 2. I break or spill things because of carelessness, not paying attention, or thinking of something else. _____ 3. I find it difficult to stay focused on what’s happening in the present. _____ 4. I tend to walk quickly to get where I’m going without paying attention to what I experience along the way. _____ 5. I tend not to notice feelings of physical tension or discomfort until they really grab my attention. -

Written Languaging, Learners' Aptitude and Second Language

Written Languaging, Learners’ Aptitude and Second Language Learning Masako Ishikawa UCL Institute of Education, University College London Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy I, Masako Ishikawa, confirm that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Where information has been derived from other sources, I confirm that this has been indicated in the thesis. Signature____________________________________________________ 1 Abstract Languaging (Swain, 2006), defined as learners’ language use to make meaning, has been suggested and identified as a way to facilitate second language (L2) learning. Most of the research conducted so far has been on oral languaging, whereas the effectiveness of written languaging (WL) in promoting L2 development remains underexplored. To help to bridge this gap, this thesis examined (1) the impact of WL on L2 learning, (2) the relationship between the frequency/quality of WL and L2 learning, and (3) the associations between L2 learning through languaging and individual differences in aptitude and metalanguage knowledge. The study used a pretest-posttest-delayed posttest design with individual written dictogloss as a treatment task. The participants were 82 adult EFL learners, assigned to three groups: +WL group, –WL group or a control group. The +WL group engaged in WL by writing about their linguistic issues when they compared their reconstructions and an original text, whereas the –WL group completed the same task without engaging in WL. The control group simply did the pre- and posttests. The assessments included an essay test, a grammar production test and a recognition test. The MLAT, LLAMA_F, and LABJ were employed as aptitude measures. A metalanguage knowledge test was also devised and administered to the participants. -

Perception Without Awareness*

PERCEPTION WITHOUT AWARENESS* Fred Dretske We appear to be on the horns of a dilemma with respect to the criteria for consciousness. Phenomenological criteria are valid by definition but do not appear to be scientific by the usual yardsticks. Behavioral criteria are scientific by definition but are not necessarily valid. --Stephen Palmer in Vision Science: Photons to Phenomenology (p. 629) Unknown to Sarah, her neighbor, a person she sees every day, is a spy. When she sees him, therefore, she sees him without awareness of either the fact that he is a spy or the fact that she sees a spy. Why, then, isn't the existence of perception without awareness (or, as some call it, implicit or subliminal perception) a familiar piece of commonsense rather than a contentious issue in psychology?1 It isn't only spies. We see armadillos, galvanometers, cancerous growths, divorcees, and poison ivy without realizing we are seeing any such thing. Most (all?) things can be, and often are (when seen at a distance or bad light), seen without awareness of what is being seen and, therefore, without awareness that one is seeing something of that sort. Why, then, is there disagreement about unconscious perception? Isn't perception without awareness the rule rather than a disputed exception to the rule? I deliberately misrepresent what perception without awareness is supposed to be in order to emphasize an important preliminary point--the difference between awareness of a stimulus (an object of some sort) and awareness of facts about it—including the fact that one is aware of it.