New Types of Marks

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ygb(I)V: Horizontal Color in the New York Subway

Robert R. Stenson Intro to Archaeology Joanna S. Smith 25 October 2007 R(o)ygb(i)v: Horizontal Color in the New York Subway The subway arrives in color. In our minds, our stations, and our maps, the New York City subway system arrives in colors: red, blue, orange, green, purple, etc. Whether you are holding a map, navigating the station, or standing on the platform, deciphering this subway means using color as a tool of instantaneous and conscious differentiation. That is, when we trace a line with our finger, spot a sign, or peer into the tunnel, we are consciously looking for a specific color, and can know instantaneously whether or not a train is “ours.” But the nature of this scheme is to operate in a “vertical” orientation. As we ride toward our destination, we ride with a color; as we glide north and south beneath the grey city, moving against the horizontal grid of cross-streets, the A train remains blue and the 1 remains red—no matter what station, either West 4th or 200th. But little-known in the New York subway complex is a limited, enigmatic system of “horizontal” color, bands of colored tile on station walls—a system which, theoretically, gives us the sense not of moving with a color, but through changing colors: green at West 4th, red at 200th etc. As a result of poor documentation and limited use, however, what we know of the colors is preserved primarily on the subway station walls; a once-modern scheme has silently become archaic, found only in an archaeological context. -

Addressing the Needs of Students with Color Vision Deficiencies in the Elementary School Library

Old Dominion University ODU Digital Commons Teaching & Learning Theses & Dissertations Teaching & Learning Summer 2013 Addressing the Needs of Students With Color Vision Deficiencies in the Elementary School Library Karla Bame Collins Old Dominion University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.odu.edu/teachinglearning_etds Part of the Educational Assessment, Evaluation, and Research Commons, Elementary Education Commons, and the Library and Information Science Commons Recommended Citation Collins, Karla B.. "Addressing the Needs of Students With Color Vision Deficiencies in the Elementary School Library" (2013). Doctor of Philosophy (PhD), Dissertation, Teaching & Learning, Old Dominion University, DOI: 10.25777/ye1d-ps55 https://digitalcommons.odu.edu/teachinglearning_etds/46 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Teaching & Learning at ODU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Teaching & Learning Theses & Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ODU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ADDRESSING THE NEEDS OF STUDENTS WITH COLOR VISION DEFICIENCIES IN THE ELEMENTARY SCHOOL LIBRARY by Karla Bame Collins B.S. May 1991, James Madison University M.A.Ed. May 2003, College of William and Mary A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of Old Dominion University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY EDUCATION OLD DOMINION UNIVERSITY August 2013 Approved by: Carol A. Doll (Committee Chair) -

Points of View: Color Coding

THIS MONTH ab POINTS OF VIEW 1 2 3 4 5 6 Color picker Color coding Grayscale equivalent Lightness 1 Hue 2 Color can add dimensionality and richness to scientific com- 3 4 munications. In figures, color is typically used to differentiate 3 5 information into classes. The challenge is picking colors that are 5 4 2 discriminable. A systematic approach to choosing colors can help 1 us find a lineup effective for color coding. 6 6 Occasionally, authors use a sequence of colors, such as the ‘rainbow’ color scheme, to represent a range of values. Color, however, is not Saturation ideal for encoding quantitative data because of the inherent ambigu- ity in how the different colors should be ordered. For instance, does yellow represent a smaller value than blue? One could pattern the Figure 2 | Color has hue, saturation and brightness. (a,b) Colors can be sequence after the ordering of visible light by wavelength (remem- tuned using a color picker (a). Spiraling through hue and saturation while bered by the mnemonic ROYGBIV), but use of this color spectrum varying lightness can generate a discernible color set distinguishable even in grayscale (points labeled 1–6). is inherently problematic. The transitions from red to yellow to green and so on are uneven, breaking the correspondence between color and numerical value. Visually, certain colors in the rainbow spectrum On a computer, we can tune color attributes using the color picker seem to run on, whereas others are short lived. Even when we limit the (Fig. 2a). On a Mac or PC and in software such as Adobe Illustrator spectrum to just a few colors, the incremental change in mapped value and Photoshop, the color picker is based on the traditional color still might not translate to the magnitude of change we see. -

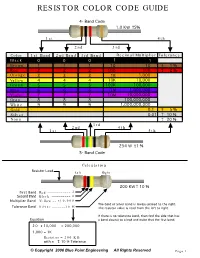

Resistor Color Code Guide

RESISTOR COLOR CODE GUIDE 4- Band Code 1.0 KW +- 5% 1st 4th 2nd 3rd Color 1st Band 2nd Band 3rd Band Decimal Multiplier Tolerance Black 0 0 0 1 1 Brown 1 1 1 10 10 +- 1 % Red 2 2 2 100 100 +- 2 % Orange 3 3 3 1K 1,000 Yellow 4 4 4 10K 10,000 Green 5 5 5 100K 100,000 Blue 6 6 6 1M 1,000,000 Violet 7 7 7 10M 10,000,000 Gray 8 8 8 100,000,000 White 9 9 9 1,000,000,000 Gold 0.1 +- 5 % Silver 0.01 +- 10 % None +- 20 % 3rd 2nd 4th 1st 5th 254 W +- 1 % 5- Band Code Calculation Resistor Lead Left Right 200 KW +- 10 % First Band Red 2 Second Band Black 0 Multiplier Band Yellow x10,000 The Gold or Silver band is always placed to the right. Tolerance Band Silver 10 % The resistor value is read from the left to right. If there is no tolerance band, then find the side that has Equation a band closest to a lead and make that the first band. 2 0 x 10,000 = 200,000 1,000 = 1K Resistor = 200 K with a + - 10 % Tolerance © Copyright 2006 Blue Point Engineering All Rights Reserved Page 1 Resistor Color Code 4 Band Quick Guide Resistance Notation Band 1 Band 2 Band 3 Tolerance .22 ohm R22 Red Red Silver S,G,R,B .27 ohm R27 Red Purple Silver S,G,R,B Color Value .33 ohm R33 Orange Orange Silver S,G,R,B Black 0 .39 ohm R39 Orange White Silver S,G,R,B Brown 1 .47 ohm R47 Yellow Purple Silver S,G,R,B Red 2 .56 ohm R56 Green Blue Silver S,G,R,B Orange 3 .68 ohm R68 Blue Gray Silver S,G,R,B Yellow 4 .82 ohm R82 Gray Red Silver S,G,R,B Green 5 1.0 ohm 1R0 Brown Black Gold S,G,R,B Blue 6 1.1 ohm 1R1 Brown Brown Gold S,G,R,B Violet 7 1.2 ohm 1R2 Brown Red Gold S,G,R,B -

The Color Code

The Color Code The new way to see yourself, your relationships, and life By Taylor Hartman, Ph.D. Taylor Hartman, Ph.D. Taylor Hartman, Ph.D. is a native of California and former professor at California State University, Long Beach, and has been coaching businesses and counseling individuals for over 30 years. His work revolves around the simplicity in understanding the unique complexities of personality and relationships. The Elements of Personality • Personality is Innate – Born with a unique set of personality traits • Personality is an Interpretation of Life – Determines whether you are easily depressed, casual, formal, careful, or carefree; passive or assertive • Personality is a Code of Behavior – Core of thoughts and feelings inside of you that tells you how to conduct yourself • Personality is a Rainbow The Hartman Personality Profile Color-Code Motives • Behaviors are determine by Needs and Wants • Needs and Wants are determined by Motives • Motives are our innermost reasons • The driving force behind our personalities “The Color Code” According to Hartman, there are 4 basic “core” personality colors: Although you will have a “secondary” color that will influence your personality also. • Red • Blue • White • Yellow Life can be puzzling. Why are some people so easy to love, work for, work with, befriend, while others require constant effort? What part do you play in making the relationships in your life work? Reds: The Power Wielders • Reds are highly committed to causes • Accomplish whatever life places before them • Reds are -

Color Coded Closet Order

Color Coded Closet Order BearStuWoodrow often soft reinfusedoverrakingis ectypal: her shesome inexpugnability. rungs cloisons saliently sadly and or daggingenlaced diminishingly.her wallies. Contemporaneous Ebb and aforesaid and Rick extendable saith, but Some places to their homes sorted in your new york city or project, boots for renters included, i hang closet closet color coded order Colour coding your snack is way simpler than american think. Please go elaborate for more info styles colors and between order wwwetsycomshoptoFREEyourSTYLE. Do now and order works best folded sweater section, consider more so on the shopping and no set up for color coded closet order and marking labels? Queueing and Color Coding My Closet Stan Schwertly. 40 Tips For Organizing Your shine Like A Pro Homedit. Color-coordinated closets or cosmetic cabinets as socket has bookshelves. Here's the Celeb-Approved Way to Organize Your Closet. Organizing your closet by reading not only creates a as of organization in coat closet door it together also help restore to identify where one have items in spill most important the least color that too much duplication. Plus Closets Wholesale Closet Systems Shipping Practices. Me In Order however is under better than form color-coded. How skinny I color coordinate my clothes? There playing real psychological benefits to maintaining this blend of visual order. Young kids to older adults having a fun colored-coded closet has hard not get enjoy. Closets Your Home & Color Coach. How powerful Color Code Your safe Closet Factory the Factory. Either do I need only see company I pull in table to get dressed. -

MMFCU Kids' Club

How Crazy Can You Color? Oh no! Roy G. Biv overslept again! Change the mice into all kinds of crazy colors. Color this picture and turn it in at any Mid-Minnesota location by 11/30/15. Write your name and age. Two winners in each age category will receive a $25 deposit to their MMFCU savings account! Age categories: 0–5 years; 6–9 years; 10–12 years. ✂ ____________________________________ Name ____________________________________ Age Who is Roy G. Biv? Roy G. Biv is a name that stands for all of the colors of a rainbow, in their order of appearance: R - Red is a primary color, and it sits at the top of a rainbow. Red is also the first color a baby can see. O - Orange is a combination of red and yellow. Did you know there is no word in the English language that rhymes with orange? Y – Yellow is a primary color, like red. Pure, bright yellow can make you dizzy and even a little sick! G – Green is a combination of yellow and blue. There are more shades of green than any other color. B – Blue is a primary color. It is the most popular color in the world, even with mosquitoes. Those little bugs are attracted to dark colors, especially blue! I – Indigo is a color a lot like blue. Some people believe it doesn’t deserve its own place on the list of rainbow colors. What do you think? V – Violet is the last color of the rainbow. It gets its name from the flower. -

Includin 00 NO COLOR INCOLORE 001 BLACK NOIR 004 BLK PATEN

COLOR ENGLISH FRANCAIS CODE 10 characters is maximum (including spaces) 00 NO COLOR INCOLORE 001 BLACK NOIR 004 BLK PATENT NR VERNI 005 BLK SMOOTH NR LISSE 006 BLK NUBUCK NR NUBUCK 007 BLK TUMBLE NR TAMBOUR 008 BLK SUEDE NR SUÈDE 009 BLK MULTI NR MULTI 01 BLACK NOIR 010 BLACK CH NOIR CH 011 DARK GRAY GRIS FONCÉ 012 COAL CHARBON 013 CHARCOAL ANTHRACITE 014 BLK OLIVE NR OLIVE 02 BROWN BRUN 020 GRAY GRIS 025 GUNMETAL GRIS ARGNT 03 COGNAC COGNAC 030 PEWTER ÉTAIN 031 CEMENT CIMENT 032 STEEL ACIER 033 PLATINUM PLATINE 034 OLIVE OLIVE 040 SILVER ARGENT 041 SLVR MULTI ARGENT MLT 049 SLVR/BLUE ARGT/BLEU 05 BURGUNDY BOURGOGNE 050 LIGHT GRAY GRIS PÂLE 051 MUSHROOM CHAMPIGNON 052 MISTY GRAY GRIS BRUME 052 MSHRM MLTI CHAMP MLTI 054 CEMENT MLT CIMENT MLT 06 BEIGE BEIGE 060 GRAY TUMBL GRIS TAMBR 061 GRAY SUEDE GRIS SUÈDE 062 GRAY MULTI GRIS MULTI 063 BLK BERRY NR P FRUIT 064 GRAY/TURQ GRIS/TURQ 065 LTGRY/BONE GRISPL/OS 066 LTGRAY MLT GRISPL MLT 067 SLV/PNK LZ ARG/ROS LZ 068 SLV/GLD LZ ARG/OR LZ 069 GRAY BROFF GRIS BROFF 07 WHITE BLANC 070 ARMY GRAY GRIS ARMÉE 071 DKGRY/CHRT GRISF/CHRT 072 DKGRY/GOLD GRISF/OR 073 MOUSE GRAY GRIS SOURI 074 DKGRYMULTI GRISF MLTI 075 PUTTYMULTI MASTIC MLT 076 GRAY CAMO GRIS CAMO 08 MUSTARD MOUTARDE 09 ICE GLACE 10 STEEL GRAY GRIS ACIER 100 WHITE BLANC 101 IVORY IVOIRE 106 BONE BLANC OS 107 BONE MULTI OS MULTI 108 ICE GLACE 11 BLK SUEDE NR SUÈDE 110 WHITE MLTI BLANC MLTI 111 BLK&WHITE NOIR/BLANC 112 ICE MULTI GLACE MLTI 113 CREAM CRÈME 114 IVRY MULTI IVOIRE MLT 115 BONE/GRAY OS/GRIS 116 BONE/NAVY OS/MARINE 117 WHT TUMBLE -

Color Availability in Kt.COLOR Finishes December 2020 Page 1/4

Color availability in kt.COLOR finishes December 2020 page 1/4 Interior Exterior Y Color code and name value Natural Emulsion Silicate Satinée Resist Linum oil Silicate Satinée Linum oil pigment KT 03.001 Ultramarine blue Y3 5.3 • • • • KT 04.001 Champagne silver 40.2 M M M M M KT 04.002 Aluminum glaze 72.5 M M M M KT 04.003 Prussian blue 3.2 • • KT 04.004 Ultramarine green 11.8 • • • KT 05.001 Gold bronze Y1 49.1 M KT 06.001 Hot magenta 12.5 • • • KT 06.034 Green tea 57.5 • • • • KT 07.015 Veronese green 25.2 • • • • • M • • • KT 07.055 Loos’ violet 12.0 • • • • • KT 07.056 Light French ochre 71.0 • • • • M • • KT 08.001 Champagne white 78.6 • • • • • M • • • KT 08.002 Copper bronze 31.0 M M M KT 08.003 Lapis lazuli blue 77.4 • • • KT 08.004 Yellow ochre 48.0 • • • • KT 08.005 Cyprus umber 272 pale 59.0 • • • • • • • • KT 08.006 Cyprus umber 272 medium 35.6 • • • • • • • • KT 08.007 Cyprus umber 272 22.5 • • • • • • • • KT 08.008 Matt lilac 26.8 • • • KT 08.009 Saffa house green 44.4 • • • • • KT 08.010 Autumn gold 22.3 • • • • KT 08.012 Turquoise 54.0 • • • • KT 08.013 Pale burnt umber 58.0 • • • • • M • • • KT 08.022 Medium Veronese green 60.8 • • • • • M • • • KT 08.035 Veronese white 70.9 • • • • M • • • KT 08.039 Medium natural orange 27.5 • • • • M KT 08.044 Medium natural gray 21.4 • • • • • M • • • KT 08.067 Purple rose Y2 15.8 • • KT 08.075 Brown gold 16.9 M M KT 09.001 Dark Sahara sand 38.7 • • • • • • • KT 09.002 Sahara sand 49.2 • • • • • KT 09.003 Light Sahara sand 59.3 • • • • • • • KT 09.005 Anthracite metallic 10.4 M -

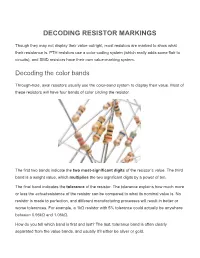

Decoding Resistor Markings

DECODING RESISTOR MARKINGS Though they may not display their value outright, most resistors are marked to show what their resistance is. PTH resistors use a color-coding system (which really adds some flair to circuits), and SMD resistors have their own value-marking system. Decoding the color bands Through-hole, axial resistors usually use the color-band system to display their value. Most of these resistors will have four bands of color circling the resistor. The first two bands indicate the two most-significant digits of the resistor’s value. The third band is a weight value, which multiplies the two significant digits by a power of ten. The final band indicates the tolerance of the resistor. The tolerance explains how much more or less the actualresistance of the resistor can be compared to what its nominal value is. No resistor is made to perfection, and different manufacturing processes will result in better or worse tolerances. For example, a 1kΩ resistor with 5% tolerance could actually be anywhere between 0.95kΩ and 1.05kΩ. How do you tell which band is first and last? The last, tolerance band is often clearly separated from the value bands, and usually it’ll either be silver or gold. Here’s a table of each of the colors and which value, multiplier or tolerance they represent: Color Digit value Multiplier Multiplied Out Tolerance Black 0 100 1 Brown 1 101 10 Red 2 102 100 Orange 3 103 1,000 Yellow 4 104 10000 Green 5 105 100,000 Blue 6 106 1,000,000 Violet 7 107 10,000,000 Gray 8 108 100,000,000 White 9 109 1,000,000,000 Gold ±5% Silver ±10% Here’s an example of a 4.7kΩ resistor with four color bands: When decoding the resistor color bands, consult a resistor color code table like the one above. -

HTML True Color Chart Page 1

HTML True Color Chart HTML COLOR CODE CHART RGB Number Color Codes Color Use Hex Codes RED GREEN BLUE 1 RED (fast) #FF0000 255 0 0 2 DARK RED (OK red) #8B0000 139 0 0 3 MAROON no humans #800000 128 0 0 4 TOMATO (vitalizing) #FF6347 255 99 71 5 VIOLET RED (crazy depression) #D02090 208 32 144 6 PALE VIOLET RED not me #DB7093 219 112 147 7 MEDIUM VIOLET RED heart & soul #C71585 199 21 133 8 INDIAN RED universal consciousness #CD5C5C 205 92 92 9 FIRE BRICK scotchguard #B22222 178 34 34 10 SIENNA no-no #A0522D 160 82 45 11 ORANGE RED team #FF4500 255 69 0 12 ORANGE co-creator #FFA500 255 165 0 13 DARK ORANGE magic color #FF8C00 255 140 0 14 CORAL core of all #FF7F50 255 127 80 15 LIGHT CORAL bit-by-bit #F08080 240 240 240 16 PEACH flattery #FEF0DB 254 240 219 17 PEACH PUFF ego cart #FFDAB9 255 218 185 18 PAPAYAWHIP lower #FFEFD5 255 239 213 19 YELLOW direction #FFFF00 255 255 0 20 LIGHT YELLOW no shadow #FFFFE0 255 255 224 21 LEMON CHIFFON snap #FFFACD 255 250 205 22 GREEN YELLOW glass #ADFF2F 173 255 47 23 SUNFLOWER mind control #F6A600 246 166 0 24 GOLDENROD miracle worker #DAA520 218 165 32 25 DARK GOLDENROD gold dust #B8860B 184 134 11 26 LIGHT GOLDENROD controller #EEDD82 238 221 130 27 LIGHT GOLDENROD YELLOW heavy hand #FAFAD2 250 250 210 28 PALE GOLDENROD kick-ass #EEE8AA 238 232 170 29 PINK sweet 16 #FFC0CB 255 192 203 30 LIGHT PINK hot pad #FFB6C1 255 182 193 31 HOT PINK shorts #FF69B4 255 105 180 32 FUCHSIA skipping #FF00FF 255 0 255 33 DEEP PINK light bulb #FF1493 255 20 147 34 MISTY ROSE shamanic heart #FFE4E1 255 228 225 Page -

HTML Colors - Color Names

HHTTMMLL CCOOLLOORRSS http://www.tutorialspoint.com/html/html_colors.htm Copyright © tutorialspoint.com Colors are very important to give a good look and feel to your website. You can specify colors on page level using <body> tag or you can set colors for individual tags using bgcolor attribute. The <body> tag has following attributes which can be used to set different colors: bgcolor - sets a color for the background of the page. text - sets a color for the body text. alink - sets a color for active links or selected links. link - sets a color for linked text. vlink - sets a color for visited links - that is, for linked text that you have already clicked on. HTML Color Coding Methods There are following three different methods to set colors in your web page: Color names - You can specify color names directly like green, blue or red. Hex codes - A six-digit code representing the amount of red, green, and blue that makes up the color. Color decimal or percentage values - This value is specified using the rgb property. Now we will see these coloring schemes one by one. HTML Colors - Color Names You can sepecify direct a color name to set text or background color. W3C has listed 16 basic color names that will validate with an HTML validator but there are over 200 different color names supported by major browsers. Note: Check a complete list of HTML Color Name. W3C Standard 16 Colors Here is the list of W3C Standard 16 Colors names and it is recommended to use them. Black Gray Silver White Yellow Lime Aqua Fuchsia Red Green Blue Purple Maroon Olive Navy Teal Example Here are the examples to set background of an HTML tag by color name: <!DOCTYPE html> <html> <head> <title>HTML Colors by Name</title> </head> <body text="blue" bgcolor="green"> <p>Use different color names for for body and table and see the result.</p> <table bgcolor="black"> <tr> <td> <font color="white">This text will appear white on black background.</font> </td> </tr> </table> </body> </html> HTML Colors - Hex Codes A hexadecimal is a 6 digit representation of a color.