Weimar Germany Still Speaks to Us

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Enchanted Catastrophe

ENCHANTED CATASTROPHE What an amazing country where the houses are taller than churches —FERNAND LÉGER AFTER VISITING THE UNITED STATES FOR THE FIRST TIME IN 19311 “What is this new religion?” he wondered, and then concluded: “It’s Wall Street that dominates this new world with all of its height.”1 Léger’s astonishment may seem dated today, when luxury high-rises and tall office buildings have come to appear more banal than transcendent, and stands in contrast to the more sensationalistic response of his friend Le Corbusier, who quipped that New York’s skyscrapers were “too small” when he visited the city four years later. Yet his ultimate point remains remarkably acute: “the vertical push is in line with the economic order.”2 For in contrast to the traditional image of the religious spire, the capitalist transformation of the tall tower typology has come to represent the Americanization of metropolitan modernity, and although ostensibly secular, it continues to be mystified to this day. The skyscraper is more than just a symbolic icon of capitalist power, however, for as Carol Willis argues in her study Form Follows Finance, it is also direct index of financial investment and real estate speculation.3 Léger apparently recognized this not long after the stock market crash of 1929 when he wrote: “Wall Street has gone too far in transforming everything into speculation. Wall Street is an amazing abstraction, but catastrophic. American vertical architecture has gone too far….”4 1. Fernand Léger, “New York,” in Fonctions de la peinture (Paris: Editions Gallimard, 2004), 152-3. -

The Critical Dimension of German Department Stores

84THACSAANNUALMEETlNG HISTORY 1996 21 5 From Messel to Mendelsohn: The Critical Dimension of German Department Stores KATHLEEN JAMES University of California, Berkeley INTRODUCTION favor of a reassuring image of historical and social continu- ity, Mendelsohn used advertising to dress up the austere The dilemma faced by many architects today of how to industrial imagery that epitomized his rejection of conven- practice within a consumer culture with which they are not tional luxury. Although conditioned in part by the individual entirely comfortable is not a new one, although the variety taste of the two architects and the different character of the of ways that earlier architects addressed it has often been department store chains who employed them, many of these overlooked in accounts that privilege style, theory, and differences are mirrored in the writings of two generations of construction over issues of use. Furthermore, the common German architecturai critics, whose attitudes toward con- assumption that the work of the heroic figures of the modem sumerism changed dramatically after World War I. movement provide an alternative to such commercialism Both Messel and Mendelsohn excelled at giving orderly, often alienates us from what we often perceive to be a new, but interesting form to urban building types (office and specifically postmodern condition. By delineating the ways apartment buildings) more typically associated with the in which two generations of German architects addressed most chaotic aspects of contemporary real estate specula- their concerns about the department store, this paper pro- tion. Each architect also managed to downplay the aspects vides some measure of precedent for an architecture which of commercialism that most distressed him and his contem- does in part critique its apparent program, while exposing the poraries while satisfying his patron's needs for environments enthusiasm for the consumer face of mass production that suitable to selling. -

The Einstein Tower, Potsdam, Germany

Case Study 12.5: The Einstein Tower, Potsdam, Germany Gudrun Wolfschmidt and Michel Cotte Presentation and analysis of the site Geographical position: Telegrafenberg 1 , 14473 Potsdam, Germany. Location : Latitude 52º 22´ 44˝ N, longitude 13º 3´ 50 E˝. Elevation 87m above mean sea level. General description: The Einstein Tower, designed by the Berlin architect Erich Mendelsohn (1857–1953) and built in the early 1920s, is both an astrophysical observatory and a masterpiece of the history of modern architecture in Germany. Brief inventory : • The tower itself is 20m high. It was constructed between 1920 and 1922, but owing to a lack of modern construction materials after World War I, the tower had to be built with bricks instead of reinforced concrete. As a protection against the wind and heating, a wood- en structure was added on the inside of the tower, and this supports the objective lens. • The instrumentation was installed in 1924. The dome is 4.5 m in diameter and contained the two 85 cm-coelostat mirrors. The lens of 60 cm aperture and 14.50 m focal length produced a solar image 14 cm in diameter. The company Zeiss of Jena was responsible for the instrumentation. • The cellar contained a room at constant temperature. Here, two high-resolution spectrographs produced solar spectra from red to violet with a length of 12 m. In 1925, a physical-spectrographic laboratory was constructed. This contained a spectral furnace as a comparison light source, an apparatus to produce an electric arc, a photoelectric Registration photometer, an electromagnet and an apparatus for the investigation of the hyperfine structure of emission lines. -

Taking a Stand? Debating the Bauhaus and Modernism, Heidelberg: Arthistoricum.Net 2021, P

The Myth of the White Bauhaus City Tel Aviv Philipp Oswalt Oswalt, Philipp, The Myth of the White Bauhaus City Tel Aviv, in: Bärnreuther, Andrea (ed.), Taking a Stand? Debating the Bauhaus and Modernism, Heidelberg: arthistoricum.net 2021, p. 397-408, https://doi.org/10.11588/arthistoricum.843.c112922 Fig. 1 Cover of the catalogue for the exhibition «White City. International Style Architecture in Israel. A Portrait of an Era», in the Tel Aviv Museum, 1984, by Michael D. Levin. (Cover picture: Leopold Krakauer, Bendori House (Teltch Hotel), 103 Derech Hayam, Haifa, 1934–35) 399 Philipp Oswalt tel aviv as bauhaus’ world capital No newspaper supplement today can fail to mention Tel Aviv as a «bauhaus» white city «Bauhaus city». Scarcely anywhere seems better suited to illustrat- social relevance of the bauhaus ing the Bauhaus’ social relevance and impact. At the same time, al- most nowhere else demonstrates more impressively how the myths bauhaus brand surrounding the Bauhaus brand have become detached from his- bauhaus myths torical realities and taken on an independent existence. The White City is anything but a genuine Bauhaus city.1 In terms of those involved, it is only marginally connected with the questioning bauhaus brand’s Bauhaus: Over two hundred architects worked in Tel Aviv in the «bauhaus» constructions 1930s, but only four of these had studied at the Bauhaus for some time.2 The percentage of Bauhaus students involved in planning Auschwitz was higher: From 1940 to 1943, Bauhaus alumnus Fritz questioning entrenched Ertl was -

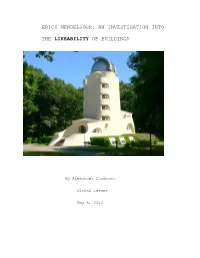

Erich Mendelsohn: an Investigation Into

ERICH MENDELSOHN: AN INVESTIGATION INTO THE LIKEABILITY OF BUILDINGS By Alexander Luckmann Global Issues May 6, 2013 Abstract In my paper, I attempted to answer a central questions about architecture: what makes certain buildings create such a strong sense of belonging and what makes others so sterile and unwelcoming. I used the work of German-born architect Erich Mendelsohn to help articulate solutions to these questions, and to propose paths of exploration for a kinder and more place-specific architecture, by analyzing the success of many of Mendelsohn’s buildings both in relation to their context and in relation to their emotional effect on the viewer/user, and by comparing this success with his less successful buildings. I compared his early masterpiece, the Einstein Tower, with a late work, the Emanue-El Community Center, to investigate this difference. I attempted to place Mendelsohn in his architectural context. I was sitting on the roof of the apartment of a friend of my mother’s in Constance, Germany, a large town or a small city, depending on one’s reference point. The apartment, where I had been frequently up until perhaps the age of six but hadn’t visited recently, is on the top floor of an old building in the city center, dating from perhaps the sixteenth or seventeenth centuries. The rooms are fairly small, but they are filled with light, and look out over the bustling downtown streets onto other quite similar buildings. Almost all these buildings have stores on the ground floor, often masking their beauty to those who don’t look up (whatever one may say about modern stores, especially chain stores, they have done a remarkable job of uglifying the street at ground level). -

Michele Stavagna Berlin/Triest

Michele Stavagna Berlin/Triest Michele Stavagna is an architect and Stavagna translated and edited the first architectural historian, who lives and Italian edition of “Die Baukunst der works in Berlin, and is the correspondent neuesten Zeit” by G. A. Platz. His research from Italy for the magazine “der architekt themes focus on the birth and affirmation - BDA”. He was educated at the Università of Modernism within the broader context IUAV of Venice (Italy), holds a degree in of the mass public and economic develop- architectural design and a PhD in history ment of the modern society. of architecture and urban design, and has taught Theory and History of Industrial Design at the Università degli Studi of Triest (Italy). The Herpich Affair 1924 | Stavagna 460 THE HERPICH AFFAIR OF 1924 Modern Architecture Challenging the Economic Establishment In 1923, Erich Mendelsohn was by far the most successful among the young Ger- man architects, having already realized many important buildings: the Einstein tower, the Steinberg-Herrmann Hat Factory, the renewal of the Mosse Publisher Building. Between 1923 and 1924 he developed the plan for the renewal and ex- pansion of the building for the Herpich Furriers on Leipziger Strasse, which was the most important commercial street in Berlin. The entangled history of the proj- ect approval and realization testifies to a crucial moment for the affirmation of modern architecture. Unfortunately, the official documentation about the Herpich store, including even the building itself, has been lost.1 The first known date regarding this project is revealed in Mendelsohn’s private correspondence to his wife on 7 April 1924. -

Erich Mendelsohn

Erich Mendelsohn (21 March 1887 – 15 September 1953) “Every building material, like every substance, has certain conditions governing the demands that can be made on it….Steel in combination with concrete, reinforced concrete, is the building material for the new formal expression, for the new style… The relation between support and load, this apparently eternal law, will also have to alter its image, for things support themselves which formerly had to be supported…” Erich Mendelsohn, letter to Luise Maas, March 14, 1914 Max Berg, Centennial Hall Breslau, Germany 1913 (now Wroclaw, Poland.) Wassily Kandinsky Max Berg, Centennial Hall Painting with White Border Breslau, Germany 1913 1913 (now Wroclaw, Poland.) Expressionism Marc Franz Wassily Kandinsk Rehe im Walde On White II Umberto Boccioni, Unique Forms of Continuity in Space, 1913 Analogy between a particular industrial technology—reinforced concrete– and the human body Newton’s fixed space Einstein’s flexible space-time Erich Mendelsohn, sketches for the Einstein Tower, Potsdam, Germany 1917 light space time “organic” shift in materials Imagery worked on several levels. It represented the: 1. Truth of reinforced concrete construction in which a steel frame or skeleton supported and stiffened the concrete flesh 2. Stresses shaping the form (the compression and tension of both reinforced concrete and the human body) 3. Intricate curved pieces of the human spine corresponded to his aesthetic taste 4. Human presence that could arouse the Erich Mendelsohn, empathy of viewers. Einstein -

Style Debates in Early 20Th-Century German Architectural Discourse

$UFKLWHFWXUDO Barnstone, DA. 2018. Style Debates in Early 20th-Century German Architectural Discourse. Architectural Histories, +LVWRULHV 6(1): 17, pp. 1–9. DOI: https://doi.org/10.5334/ah.300 RESEARCH ARTICLE Style Debates in Early 20th-Century German Architectural Discourse Deborah Ascher Barnstone In spite of the negative connotations ‘style’ has in contemporary architectural discourse, in early 20th- century Germany there was no consensus on the meaning or value of the concept amongst architects and critics. Although style was a dirty word for some like Hermann Muthesius, it represented the pinnacle of achievement for others like Walter Curt Behrendt. Against the backdrop of Behrendt’s famous Victory of the New Building Style, of 1927, were very diverse understandings of the term. This plurality was partly due to conceptual confusion between ‘the styles’ and ‘style’, but it was also a legacy of Gottfried Semper’s and Alois Riegl’s respective efforts to resituate style as a practical and historiographical tool. Although style was endlessly debated between 1910 and 1930 by German architects, critics, and intel- lectuals of all stripes, later scholars have either largely overlooked its significance or used the term as a way of describing a particular group of works with a narrow set of formal tropes. The debates, the conceptual confusion, and the incredible variety of opinion over style in early 20th-century discourse have not been addressed, especially in relation to practicing architects. This essay examines some of the intersecting positions of several important German practitioners to show how the notion of style served as a conceptual framework for divergent modern practices. -

Erich Mendelsohn: German- That Evening

Carlos Scarpa, Berkeley, California, 1969. CARLO SCARPA { IN PERSON } By Max Levy architecture history courses, my introduction to In September and October 2007, the Gerald D. Hines Scarpa was up close and personal. He came to Berkeley to refine the exhibition design on-site and to supervise its installation. A few days before the College of Architecture at the University of Houston show opened, I came across a small poster announc- ing that Professor Scarpa would lecture on his work hosted the exhibition Erich Mendelsohn: German- that evening. Though the eminent historian Vincent Scully would eventually place Scarpa “somewhere between Wright and Kahn,” I found no one at the American Architect, 1887–1953, organized by architecture school that day who had heard of him. I went to the lecture anyway. In a room that would have seated 300 people, only five showed up. This Mendelsohn’s biographer Regina Stephan for the prompted much animated discussion between Scarpa and his interpreter, and soon we heard from Institut für Auslandsbeziehungen Stuttgart. Dallas the lectern: “Professor Scarpa feels this room is too large for such a small group. We must move to a . space better tailored to the scale of the gathering.” E V I H architect Max Levy reflects on an earlier exhibition Scarpa waited with genial forbearance, chain- C R A smoking and smiling over at us occasionally, while M L I F the search went on for another venue. We sat there C I of Mendelsohn’s drawings in an installation designed F I silently, too self-conscious to bail out of the awkward C A P situation. -

Einstein Tower

Lauren MacKenzie Diagramming: Form Body Technique Space EVDA 621 E i n s t e i n T o w e r FORM - EINSTEIN TOWER grid represents single uniform Erich Mendelsohn, architect of the Einstein incoming light beam Tower, took inspiration from Einstein’s theory of relativity were light bends around objects due to imposed gravitational forces. Mendelsohn envisioned a new monolithic concrete tower which aimed to streamline exteriors with organically flowing interiors that defied traditional structural law (Pearson, 2001). The challenge was to still have the building function as a working observatory while not sacrificing the desired form. “Mendelsohn did not deny his ignorance regarding the practical aspects of a working observatory and was open to constructive criticism” (Hentschel, 1997, p. 55). Mendelsohn spoke often with his close friend Erwin Freundlich, an astronomer/ Einstein’s assistant, about how the building had to functionally be able to perform. After learning that the form, mostly layout, of the interior tower and subterranean floors was fixed in size and dimension due to the requirements of a working observatory, Mendelsohn shifted his focus to the rest of the building which was fair game for him to design. The exterior Expressionist architecture that emerged was seen to be unusual and “a little capricious… the stylistic language [did] not in any way suit the other buildings of the Astrophysical Institute” (Hentschel, 1997, p. 62) but due to the political situation of Germany post WWI, the Nation was in a hurry to build a monument in Einstein’s honour. “Thanks to the runaway inflation rate, such reservations about the design were briskly swept aside by decree at the highest cabinet levels, so as not to delay start of construction” (Hentschel, 1997, p. -

The Photography of Eric Mendelsohn and Wolfgang Tillmans

Critical Approaches to Architectural Environments: The Photography of Eric Mendelsohn and Wolfgang Tillmans Item Type text; Electronic Thesis Authors Hayt, Andrew Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 07/10/2021 13:25:41 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/624142 CRITICAL APPROACHES TO ARCHITECTURAL ENVIRONMENTS: THE PHOTOGRAPHY OF ERIC MENDELSOHN AND WOLFGANG TILLMANS by Andrew C. Hayt ____________________________ Copyright © Andrew C. Hayt 2017 A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the SCHOOL OF ART In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS WITH A MAJOR IN ART HISTORY In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 2017 Hayt 2 STATEMENT BY AUTHOR The thesis titled Critical Approaches to Architectural Environments: The Photography of Eric Mendelsohn and Wolfgang Tillmans prepared by Andrew C. Hayt has been submitted in partial fulfillment of requirements for a master’s degree at the University of Arizona and is deposited in the University Library to be made available to borrowers under rules of the Library. Brief quotations from this thesis are allowable without special permission, provided that an accurate acknowledgement of the source is made. Requests for permission for extended quotation from or reproduction of this manuscript in whole or in part may be granted by the copyright holder. SIGNED: Andrew C. Hayt APPROVAL BY THESIS DIRECTOR This thesis has been approved on the date shown below: Defense date Dr. -

Image and the Space of the Modern City in Erich Mendelsohn's Amerika

Image and the Space of On the other hand there is the attempt of the architect to express the topics and the potentialities the Modern City in of new architecture inside the modern cities in a new language. This ambiguity is already in the title Erich Mendelsohn’s to recognize: Amerika: Bilderbuch eines Architekten. That means the description of the brutal experience Amerika: Bilderbuch of the cultural shift between old and new world, but together a rethinking about it from a position eines Architekten1 of specific distance (i. e. led by an architect). It is not coincidence that Mendelsohn in his letters described this journey experience as a ”voyage of investigation for eye and brain“.6 Michele Stavagna He wanted to present to the readers straight this entire investigation and the practical develop- ments resulting from it. Here the main difference of his volume compared with American reports or more elaborated studies by other European archi- tects during the Twenties, like the later work by Walther C. Behrendt or the two books by his for- In December 1925 the photobook Amerika by Erich mer employee Richard Neutra.7 Mendelsohn was published. This volume contains In all these contributions the attached pictures mainly the photographs, which the architect had are only illustrations; the emphasis is on the de- taken or borrowed during his study journey to the scription, which tries to be a scientific one. So the United States of America one year before.2 experience of the reader must remain limited, as if The book became a successful bestseller. During he would observe a phenomenon under the micros- the following two years five new editions appeared.