The Return of Expressionism and the Architecture of Luigi Moretti

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Summer 2019 Director’S Letter

Summer 2019 Director’s Letter Dear Members, Summer in the Northwest is a glorious time of year. It is also notoriously busy. If you are like most people, you are eager fill your weekends with fun and adventure. Whether you are re-visiting some of your favorite places or discovering new ones, I hope Maryhill is on your summer short list. We certainly have plenty to tempt you. On July 13 we open the special exhibition West Coast Woodcut: Contemporary Relief Prints by Regional Artists, which showcases some of the best printmakers of the region. The 60 prints on view feature masterfully rendered landscapes, flora and fauna of the West coast, along with explorations of social and environmental issues. Plein air artists will be back in action this summer when the 2019 Pacific Northwest Plein Air in the Columbia River Gorge kicks off in late July; throughout August we will exhibit their paintings in the museum’s M.J. Murdock Charitable Trust Education Center. The show is always a delight and I look forward to seeing the Gorge through the eyes of these talented artists. Speaking of the Gorge — we are in the thick of it with the Exquisite Gorge Project, a collaborative printmaking effort that has brought together 11 artists to create large-scale woodblock prints reflective of a 220-mile stretch of the Columbia River. On August 24 we invite you to participate in the culmination of the project as the print blocks are inked, laid end-to-end and printed using a steamroller on the grounds at Maryhill. -

Bauhaus 1 Bauhaus

Bauhaus 1 Bauhaus Staatliches Bauhaus, commonly known simply as Bauhaus, was a school in Germany that combined crafts and the fine arts, and was famous for the approach to design that it publicized and taught. It operated from 1919 to 1933. At that time the German term Bauhaus, literally "house of construction" stood for "School of Building". The Bauhaus school was founded by Walter Gropius in Weimar. In spite of its name, and the fact that its founder was an architect, the Bauhaus did not have an architecture department during the first years of its existence. Nonetheless it was founded with the idea of creating a The Bauhaus Dessau 'total' work of art in which all arts, including architecture would eventually be brought together. The Bauhaus style became one of the most influential currents in Modernist architecture and modern design.[1] The Bauhaus had a profound influence upon subsequent developments in art, architecture, graphic design, interior design, industrial design, and typography. The school existed in three German cities (Weimar from 1919 to 1925, Dessau from 1925 to 1932 and Berlin from 1932 to 1933), under three different architect-directors: Walter Gropius from 1919 to 1928, 1921/2, Walter Gropius's Expressionist Hannes Meyer from 1928 to 1930 and Ludwig Mies van der Rohe Monument to the March Dead from 1930 until 1933, when the school was closed by its own leadership under pressure from the Nazi regime. The changes of venue and leadership resulted in a constant shifting of focus, technique, instructors, and politics. For instance: the pottery shop was discontinued when the school moved from Weimar to Dessau, even though it had been an important revenue source; when Mies van der Rohe took over the school in 1930, he transformed it into a private school, and would not allow any supporters of Hannes Meyer to attend it. -

A Historiography of Musical Historicism: the Case Of

A HISTORIOGRAPHY OF MUSICAL HISTORICISM: THE CASE OF JOHANNES BRAHMS THESIS Presented to the Graduate Council of Texas State University-San Marcos in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of MUSIC by Shao Ying Ho, B.M. San Marcos, Texas May 2013 A HISTORIOGRAPHY OF MUSICAL HISTORICISM: THE CASE OF JOHANNES BRAHMS Committee Members Approved: _____________________________ Kevin E. Mooney, Chair _____________________________ Nico Schüler _____________________________ John C. Schmidt Approved: ___________________________ J. Michael Willoughby Dean of the Graduate College COPYRIGHT by Shao Ying Ho 2013 FAIR USE AND AUTHOR’S PERMISSION STATEMENT Fair Use This work is protected by the Copyright Laws of the United States (Public Law 94-553, section 107). Consistent with fair use as defined in the Copyright Laws, brief quotations from this material are allowed with proper acknowledgement. Use of this material for financial gain without the author’s express written permission is not allowed. Duplication Permission As the copyright holder of this work, I, Shao Ying Ho, authorize duplication of this work, in whole or in part, for educational or scholarly purposes only. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS My first and foremost gratitude is to Dr. Kevin Mooney, my committee chair and advisor. His invaluable guidance, stimulating comments, constructive criticism, and even the occasional chats, have played a huge part in the construction of this thesis. His selfless dedication, patience, and erudite knowledge continue to inspire and motivate me. I am immensely thankful to him for what I have become in these two years, both intellectually and as an individual. I am also very grateful to my committee members, Dr. -

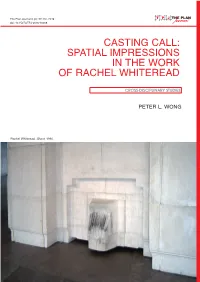

Casting Call: Spatial Impressions in the Work of Rachel Whiteread

The Plan Journal 0 (0): 97-110, 2016 doi: 10.15274/TPJ-2016-10008 CASTING CALL: SPATIAL IMPRESSIONS IN THE WORK OF RACHEL WHITEREAD CROSS-DISCIPLINARY STUDIES PETER L. WONG Rachel Whiteread, Ghost, 1990. Casting Call: Spatial Impressions in the Work of Rachel Whiteread Peter L. Wong ABSTRACT - For more than 20 years, Rachel Whiteread has situated her sculpture inside the realm of architecture. Her constructions elicit a connection between: things and space, matter and memory, assemblage and wholeness by drawing us toward a reciprocal relationship between objects and their settings. Her chosen means of casting solids from “ready- made” objects reflect a process of visual estrangement that is dependent on the original artifact. The space beneath a table, the volume of a water tank, or the hollow undersides of a porcelain sink serve as examples of a technique that aligns objet-trouvé with a reverence for the everyday. The products of this method, now rendered as space, acquire their own autonomous presence as the formwork of things is replaced by space as it solidifies and congeals. The effect is both reliant and independent, familiar yet strange. Much of the writing about Whiteread’s work occurs in the form of art criticism and exhibition reviews. Her work is frequently under scrutiny, fueled by the popular press and those holding strict values and expectations of public art. Little is mentioned of the architectural relevance of her process, though her more controversial pieces are derived from buildings themselves – e,g, the casting of surfaces (Floor, 1995), rooms (Ghost, 1990 and The Nameless Library, 2000), or entire buildings (House, 1993). -

Classicism, Modernism, Postmodernism, and Importance of Communication

Classicism, Modernism, Postmodernism, and Importance of Communication Taylor Stevenson Art History II Prof Jason Bernagozzi Midterm Exam March 09, 2016 Art and societies have long since been integrated, with both realms reflecting each other through understandings, values, and ideas. When either realm changes its ideologies, the other realm tends to reflect those changes in a similar form. This is prevalent in the understanding of art movements over the course of history, especially with three periods of art: Classicism, Modernism, and Post Modernism. Through these art movement periods, we can see how ideologies of the artist have evolved from working for other professions that use art as a means to an end, to using art as a way to communicate their own ideas, to creating art for the viewer to decide on the meaning. Many artworks that were taken from (or inspired by) Greek and Roman cultural art are considered to be classical. This may be because at this point in time, the societies behind these works of art have established an aesthetic standard that serves as a fundamental basis for other art movements. The Editors of Encyclopædia Britannica note “’classic’ is also sometimes used to refer to a stage of development that some historians have identified as a regular feature of what they have seen as the cyclical development of all styles.” When applied to art (especially art in the western/European world), these “classic” greek and roman roots placed emphasis on a realistic form, and line over color in two dimensional pieces1. Sculptures of these times, while considered important, did not necessarily translate into the aesthetic view of the next generation. -

Protecting Postmodern Historicism: Identification, Ve Aluation, and Prescriptions for Preeminent Sites

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Theses (Historic Preservation) Graduate Program in Historic Preservation 2013 Protecting Postmodern Historicism: Identification, vE aluation, and Prescriptions for Preeminent Sites Jonathan Vimr University of Pennsylvania Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/hp_theses Part of the Historic Preservation and Conservation Commons Vimr, Jonathan, "Protecting Postmodern Historicism: Identification, vE aluation, and Prescriptions for Preeminent Sites" (2013). Theses (Historic Preservation). 211. https://repository.upenn.edu/hp_theses/211 Suggested Citation: Vimr, Jonathan (2013). Protecting Postmodern Historicism: Identification, vE aluation, and Prescriptions for Preeminent Sites. (Masters Thesis). University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA. This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/hp_theses/211 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Protecting Postmodern Historicism: Identification, vE aluation, and Prescriptions for Preeminent Sites Abstract Just as architectural history traditionally takes the form of a march of styles, so too do preservationists repeatedly campaign to save seminal works of an architectural manner several decades after its period of prominence. This is currently happening with New Brutalism and given its age and current unpopularity will likely soon befall postmodern historicism. In hopes of preventing the loss of any of the manner’s preeminent works, this study provides professionals with a framework for evaluating the significance of postmodern historicist designs in relation to one another. Through this, the limited resources required for large-scale preservation campaigns can be correctly dedicated to the most emblematic sites. Three case studies demonstrate the application of these criteria and an extended look at recent preservation campaigns provides lessons in how to best proactively preserve unpopular sites. -

Modernism Without Modernity: the Rise of Modernist Architecture in Mexico, Brazil, and Argentina, 1890-1940 Mauro F

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Management Papers Wharton Faculty Research 6-2004 Modernism Without Modernity: The Rise of Modernist Architecture in Mexico, Brazil, and Argentina, 1890-1940 Mauro F. Guillen University of Pennsylvania Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/mgmt_papers Part of the Architectural History and Criticism Commons, and the Management Sciences and Quantitative Methods Commons Recommended Citation Guillen, M. F. (2004). Modernism Without Modernity: The Rise of Modernist Architecture in Mexico, Brazil, and Argentina, 1890-1940. Latin American Research Review, 39 (2), 6-34. http://dx.doi.org/10.1353/lar.2004.0032 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/mgmt_papers/279 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Modernism Without Modernity: The Rise of Modernist Architecture in Mexico, Brazil, and Argentina, 1890-1940 Abstract : Why did machine-age modernist architecture diffuse to Latin America so quickly after its rise in Continental Europe during the 1910s and 1920s? Why was it a more successful movement in relatively backward Brazil and Mexico than in more affluent and industrialized Argentina? After reviewing the historical development of architectural modernism in these three countries, several explanations are tested against the comparative evidence. Standards of living, industrialization, sociopolitical upheaval, and the absence of working-class consumerism are found to be limited as explanations. As in Europe, Modernism -

Master Artist of Art Nouveau

Mucha MASTER ARTIST OF ART NOUVEAU October 14 - Novemeber 20, 2016 The Florida State University Museum of Fine Arts Design: Stephanie Antonijuan For tour information, contact Viki D. Thompson Wylder at (850) 645-4681 and [email protected]. All images and articles in this Teachers' Packet are for one-time educational use only. Table of Contents Letter to the Educator ................................................................................ 4 Common Core Standards .......................................................................... 5 Alphonse Mucha Biography ...................................................................... 6 Artsits and Movements that Inspired Alphonse Mucha ............................. 8 What is Art Nouveau? ................................................................................ 10 The Work of Alphonse Mucha ................................................................... 12 Works and Movements Inspired by Alphonse Mucha ...............................14 Lesson Plans .......................................................................................... Draw Your Own Art Nouveau Tattoo Design .................................... 16 No-Fire Art Nouveau Tiles ............................................................... 17 Art Nouveau and Advertising ........................................................... 18 Glossary .................................................................................................... 19 Bibliography ............................................................................................. -

American Abstract Expressionism

American Abstract Expressionism Cross-Curricular – Art and Social Studies Grades 7–12 Lesson plan and artwork by Edwin Leary, Art Consultant, Florida Description Directions This project deals with the infusion between Art History Teacher preparation: and Art Making through American Abstract Expressionism. Gather examples of artists that dominated this movement, American Abstract Expressionism is truly a U.S. movement that display them in the Art Room with questions of: Who uses emphasizes the act of painting, inherent in the color, texture, organic forms? Dripped and splashed work? Why the highly action, style and the interaction of the artist. It may have been colored work of Kandinsky? Why the figurative aspects of inspired by Hans Hofmann, Arshile Gorky and further developed DeKooning? by the convergence of such artists as Jackson Pollack, William With the students: DeKooning, Franz Kline, Mark Rothko and Wassily Kandinsky. 1 Discuss the emotions, color and structure of the displayed Objectives artists’ work. Discuss why American Abstract Expressionism is less about • Students can interactively apply an art movement to an art 2 process-painting. style than attitude. • This art-infused activity strengthens their observation and 3 Discuss why these artists have such an attachment of self awareness of a specific artist’s expression. expression as found in their paintings yet not necessarily found in more academic work? Lesson Plan Extensions 4 Gather the materials and explain why the vivid colors of Apply this same concept of investigation, application and art Fluorescent Acrylics were used, and what they do within a making to other movements or schools of art. -

Watergate Landscaping Watergate Innovation

Innovation Watergate Watergate Landscaping Landscape architect Boris Timchenko faced a major challenge Located at the intersections of Rock Creek Parkway and in creating the interior gardens of Watergate as most of the Virginia and New Hampshire Avenues, with sweeping views open grass area sits over underground parking garages, shops of the Potomac River, the Watergate complex is a group of six and the hotel meeting rooms. To provide views from both interconnected buildings built between 1964 and 1971 on land ground level and the cantilivered balconies above, Timchenko purchased from Washington Gas Light Company. The 10-acre looked to the hanging roof gardens of ancient Babylon. An site contains three residential cooperative apartment buildings, essential part of vernacular architecture since the 1940s, green two office buildings, and a hotel. In 1964, Watergate was the roofs gained in popularity with landscapers and developers largest privately funded planned urban renewal development during the 1960s green awareness movement. At Watergate, the (PUD) in the history of Washington, DC -- the first project to green roof served as camouflage for the underground elements implement the mixed-use rezoning adopted by the District of of the complex and the base of a park-like design of pools, Columbia in 1958, as well as the first commercial project in the fountains, flowers, open courtyards, and trees. USA to use computers in design configurations. With both curvilinear and angular footprints, the configuration As envisioned by famed Italian architect Dr. Luigi Moretti, and of the buildings defines four distinct areas ranging from public, developed by the Italian firm Società Generale Immobiliare semi-public, and private zones. -

The Russian Avant-Garde 1912-1930" Has Been Directedby Magdalenadabrowski, Curatorial Assistant in the Departmentof Drawings

Trustees of The Museum of Modern Art leV'' ST,?' T Chairm<ln ,he Boord;Ga,dner Cowles ViceChairman;David Rockefeller,Vice Chairman;Mrs. John D, Rockefeller3rd, President;Mrs. Bliss 'Ce!e,Slder";''i ITTT V P NealJ Farrel1Tfeasure Mrs. DouglasAuchincloss, Edward $''""'S-'ev C Burdl Tn ! u o J M ArmandP Bar,osGordonBunshaft Shi,| C. Burden,William A. M. Burden,Thomas S. Carroll,Frank T. Cary,Ivan Chermayeff, ai WniinT S S '* Gianlui Gabeltl,Paul Gottlieb, George Heard Hdmilton, Wal.aceK. Harrison, Mrs.Walter Hochschild,» Mrs. John R. Jakobson PhilipJohnson mM'S FrankY Larkin,Ronalds. Lauder,John L. Loeb,Ranald H. Macdanald,*Dondd B. Marron,Mrs. G. MaccullochMiller/ J. Irwin Miller/ S.I. Newhouse,Jr., RichardE Oldenburg,John ParkinsonIII, PeterG. Peterson,Gifford Phillips, Nelson A. Rockefeller* Mrs.Albrecht Saalfield, Mrs. Wolfgang Schoenborn/ MartinE. Segal,Mrs Bertram Smith,James Thrall Soby/ Mrs.Alfred R. Stern,Mrs. Donald B. Straus,Walter N um'dWard'9'* WhlTlWheeler/ Johni hTO Hay Whitney*u M M Warbur Mrs CliftonR. Wharton,Jr., Monroe * HonoraryTrustee Ex Officio 0'0'he "ri$°n' Ctty ot^New^or^ °' ' ^ °' "** H< J Goldin Comptrollerat the Copyright© 1978 by TheMuseum of ModernArt All rightsreserved ISBN0-87070-545-8 TheMuseum of ModernArt 11West 53 Street,New York, N.Y 10019 Printedin the UnitedStates of America Foreword Asa resultof the pioneeringinterest of its first Director,Alfred H. Barr,Jr., TheMuseum of ModernArt acquireda substantialand uniquecollection of paintings,sculpture, drawings,and printsthat illustratecrucial points in the Russianartistic evolution during the secondand third decadesof this century.These holdings have been considerably augmentedduring the pastfew years,most recently by TheLauder Foundation's gift of two watercolorsby VladimirTatlin, the only examplesof his work held in a public collectionin the West. -

Staging Revolution: the Constructivist Debate About Composition

Staging Revolution: The Constructivist Debate about Composition Introduction Among the relatively few areas of agreement after the 1917 Russian Revolution, two are particularly noteworthy. The first is the widespread perception that the urban environment was chaotic. Whereas few people agreed as to the source of this chaos (choosing to blame it on the capitalists, the architects, or the intelligentsia), almost everyone believed that urban life after the revolution did not justify the sacrifices and traumas imposed by three years of civil war. The second area of agreement concerned the role of the theater: despite continued and almost irreconcilable differences about what the future should look like, there was almost complete agreement that art and theater could be “weapons” or tools in the revolution. Theater, in particular, would lead the way: from Lenin’s project for monumental propaganda (1918) to the Russian futurists’ declaration that the “streets should be a holiday of art for the people,” there was widespread agreement that art should be taken to the streets, that it was capable of communicating messages in a voice which would be understood, and that theatricality was the key to the unification of the arts. Ironically, one of the reasons why constructivism has been so difficult to study is the fact that it was long understood as a form of art which was against the creation of art. But one of the core values of constructivism was not the rejection of art but the belief that the only type of art which has meaning is one which challenges boundaries and definitions, and that part of this challenge concerns the relationship between the audience and the art work, whether we talk about theater, cinema, photography, or objects.