Enchanted Catastrophe

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Reactionary Postmodernism? Neoliberalism, Multiculturalism, the Internet, and the Ideology of the New Far Right in Germany

University of Vermont ScholarWorks @ UVM UVM Honors College Senior Theses Undergraduate Theses 2018 Reactionary Postmodernism? Neoliberalism, Multiculturalism, the Internet, and the Ideology of the New Far Right in Germany William Peter Fitz University of Vermont Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uvm.edu/hcoltheses Recommended Citation Fitz, William Peter, "Reactionary Postmodernism? Neoliberalism, Multiculturalism, the Internet, and the Ideology of the New Far Right in Germany" (2018). UVM Honors College Senior Theses. 275. https://scholarworks.uvm.edu/hcoltheses/275 This Honors College Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Undergraduate Theses at ScholarWorks @ UVM. It has been accepted for inclusion in UVM Honors College Senior Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ UVM. For more information, please contact [email protected]. REACTIONARY POSTMODERNISM? NEOLIBERALISM, MULTICULTURALISM, THE INTERNET, AND THE IDEOLOGY OF THE NEW FAR RIGHT IN GERMANY A Thesis Presented by William Peter Fitz to The Faculty of the College of Arts and Sciences of The University of Vermont In Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements For the Degree of Bachelor of Arts In European Studies with Honors December 2018 Defense Date: December 4th, 2018 Thesis Committee: Alan E. Steinweis, Ph.D., Advisor Susanna Schrafstetter, Ph.D., Chairperson Adriana Borra, M.A. Table of Contents Introduction 1 Chapter One: Neoliberalism and Xenophobia 17 Chapter Two: Multiculturalism and Cultural Identity 52 Chapter Three: The Philosophy of the New Right 84 Chapter Four: The Internet and Meme Warfare 116 Conclusion 149 Bibliography 166 1 “Perhaps one will view the rise of the Alternative for Germany in the foreseeable future as inevitable, as a portent for major changes, one that is as necessary as it was predictable. -

Das Reich Der Seele Walther Rathenau’S Cultural Pessimism and Prussian Nationalism ~ Dieuwe Jan Beersma

Das Reich der Seele Walther Rathenau’s Cultural Pessimism and Prussian Nationalism ~ Dieuwe Jan Beersma 16 juli 2020 Master Geschiedenis – Duitslandstudies, 11053259 First supervisor: dhr. dr. A.K. (Ansgar) Mohnkern Second supervisor: dhr. dr. H.J. (Hanco) Jürgens Abstract Every year the Rathenau Stiftung awards the Walther Rathenau-Preis to international politicians to spread Rathenau’s ideas of ‘democratic values, international understanding and tolerance’. This incorrect perception of Rathenau as a democrat and a liberal is likely to have originated from the historiography. Many historians have described Rathenau as ‘contradictory’, claiming that there was a clear and problematic distinction between Rathenau’s intellectual theories and ideas and his political and business career. Upon closer inspection, however, this interpretation of Rathenau’s persona seems to be fundamentally incorrect. This thesis reassesses Walther Rathenau’s legacy profoundly by defending the central argument: Walther Rathenau’s life and motivations can first and foremost be explained by his cultural pessimism and Prussian nationalism. The first part of the thesis discusses Rathenau’s intellectual ideas through an in-depth analysis of his intellectual work and the historiography on his work. Motivated by racial theory, Rathenau dreamed of a technocratic utopian German empire led by a carefully selected Prussian elite. He did not believe in the ‘power of a common Europe’, but in the power of a common German Europe. The second part of the thesis explicates how Rathenau’s career is not contradictory to, but actually very consistent with, his cultural pessimism and Prussian nationalism. Firstly, Rathenau saw the First World War as a chance to transform the economy and to make his Volksstaat a reality. -

The Critical Dimension of German Department Stores

84THACSAANNUALMEETlNG HISTORY 1996 21 5 From Messel to Mendelsohn: The Critical Dimension of German Department Stores KATHLEEN JAMES University of California, Berkeley INTRODUCTION favor of a reassuring image of historical and social continu- ity, Mendelsohn used advertising to dress up the austere The dilemma faced by many architects today of how to industrial imagery that epitomized his rejection of conven- practice within a consumer culture with which they are not tional luxury. Although conditioned in part by the individual entirely comfortable is not a new one, although the variety taste of the two architects and the different character of the of ways that earlier architects addressed it has often been department store chains who employed them, many of these overlooked in accounts that privilege style, theory, and differences are mirrored in the writings of two generations of construction over issues of use. Furthermore, the common German architecturai critics, whose attitudes toward con- assumption that the work of the heroic figures of the modem sumerism changed dramatically after World War I. movement provide an alternative to such commercialism Both Messel and Mendelsohn excelled at giving orderly, often alienates us from what we often perceive to be a new, but interesting form to urban building types (office and specifically postmodern condition. By delineating the ways apartment buildings) more typically associated with the in which two generations of German architects addressed most chaotic aspects of contemporary real estate specula- their concerns about the department store, this paper pro- tion. Each architect also managed to downplay the aspects vides some measure of precedent for an architecture which of commercialism that most distressed him and his contem- does in part critique its apparent program, while exposing the poraries while satisfying his patron's needs for environments enthusiasm for the consumer face of mass production that suitable to selling. -

Weimar Germany Still Speaks to Us

© Copyright, Princeton University Press. No part of this book may be distributed, posted, or reproduced in any form by digital or mechanical means without prior written permission of the publisher. INTRODUCTION Weimar Germany still speaks to us. Paintings by George Grosz and Max Beckmann are much in demand and hang in muse- ums and galleries from Sydney to Los Angeles to St. Petersburg. Bertolt Brecht and Kurt Weill’s The Threepenny Opera is periodically revived in theaters around the world and in many different lan- guages. Thomas Mann’s great novel The Magic Mountain, first pub- lished in 1925, remains in print and, if not exactly a household item, is read and discussed in literature and philosophy classes at count- less colleges and universities. Contemporary kitchen designs invoke the styles of the 1920s and the creative work of the Bauhaus. Post- modern architects may have abandoned the strict functionalism of Walter Gropius, but who can resist the beauty of Erich Mendelsohn’s Columbus House or his Schocken department stores (only one of which is still standing), with their combination of clean lines and dynamic movement, or the whimsy of his Einstein Tower? Hannah Höch might not be as widely known as these others, but viewers who encounter her work today are drawn to her inventive combination of primitivist and modernist styles, her juxtaposition of African or Polynesian-style masks with the everyday objects of the 1920s. The deep philosophical speculations of Martin Heidegger and the layered essays of Siegfried Kracauer, both grappling with the meaning of ad- vanced technology and mass society, still offer a wealth of insight into the modern condition. -

The Einstein Tower, Potsdam, Germany

Case Study 12.5: The Einstein Tower, Potsdam, Germany Gudrun Wolfschmidt and Michel Cotte Presentation and analysis of the site Geographical position: Telegrafenberg 1 , 14473 Potsdam, Germany. Location : Latitude 52º 22´ 44˝ N, longitude 13º 3´ 50 E˝. Elevation 87m above mean sea level. General description: The Einstein Tower, designed by the Berlin architect Erich Mendelsohn (1857–1953) and built in the early 1920s, is both an astrophysical observatory and a masterpiece of the history of modern architecture in Germany. Brief inventory : • The tower itself is 20m high. It was constructed between 1920 and 1922, but owing to a lack of modern construction materials after World War I, the tower had to be built with bricks instead of reinforced concrete. As a protection against the wind and heating, a wood- en structure was added on the inside of the tower, and this supports the objective lens. • The instrumentation was installed in 1924. The dome is 4.5 m in diameter and contained the two 85 cm-coelostat mirrors. The lens of 60 cm aperture and 14.50 m focal length produced a solar image 14 cm in diameter. The company Zeiss of Jena was responsible for the instrumentation. • The cellar contained a room at constant temperature. Here, two high-resolution spectrographs produced solar spectra from red to violet with a length of 12 m. In 1925, a physical-spectrographic laboratory was constructed. This contained a spectral furnace as a comparison light source, an apparatus to produce an electric arc, a photoelectric Registration photometer, an electromagnet and an apparatus for the investigation of the hyperfine structure of emission lines. -

Manchin on Lepenies, 'The Seduction of Culture in German History'

H-Nationalism Manchin on Lepenies, 'The Seduction of Culture in German History' Review published on Sunday, October 1, 2006 Wolf Lepenies. The Seduction of Culture in German History. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2006. 270 pp. $24.95 (cloth), ISBN 978-0-691-12131-4. Reviewed by Anna Manchin (Department of History, Brown University) Published on H-Nationalism (October, 2006) The Life and Politics of an Idea Wolf Lepenies, one of Germany's foremost public intellectuals, has written a fascinating and chilling essay on the seemingly unshakable German "attitude" of valuing culture over politics. This attitude contributed not only to the rise of fascism; it also accounted for the historian Friedrich Meinecke's conviction that, in the aftermath of World War II, Germany did not need a political reckoning, but an "intensified development of the Germans' inner existence," preferably in spiritual-religious Goethe communities. Fritz Stern's notion of a specific "Germanic spirit" and various revisions of it were crucial to the writing of an earlier generation of intellectual historians (including George Mosse, Fritz Ringer, and Peter Gay) who searched for an explanation for fascism's quick and easy rise to power in a nation of Germany's intellectual and cultural heritage. They all found an answer in German culture's romantic, anti-rationalist, and anti-democratic tendencies; a new mix of romanticism and technology, along with a lack of a liberal political tradition; the specific experience and spiritual mode of German society after the war; and the German tendency to embrace "art as a model for life," and they all agreed that cultural climate was important for politics. -

S.No Eser Adı Yazar 1 1. Uluslararası Avrupa Birliği, Demokrasi, Vatandaşlık Ve Vatandaşlık Eğitimi Sempozyumu, 28-30 20

SİYASET BİLİMİ VE ULUSLAR ARASI İLİŞKİLER YÜKSEK LİSANS PROGRAMI S.No Eser Adı Yazar 1. Uluslararası Avrupa Birliği, Demokrasi, Vatandaşlık ve Vatandaşlık Eğitimi 1 Sempozyumu, 28-30 2009 Uşak: bildiriler = I. International European Union, Democracy, Citizenship and Citizenship Education Symposium, 28th-30th May 2009 1. Uluslararası Avrupa Birliği, Demokrasi, Vatandaşlık ve Vatandaşlık Eğitimi 2 Sempozyumu, 28-30 2009 Uşak: bildiriler = I. International European Union, Democracy, Citizenship and Citizenship Education Symposium, 28th-30th May 2009 1. Uluslararası Plevne Kahramanı Gazi Osman Paşa ve Dönemi (1833-1900) Uluslararası Plevne Kahramanı Sempozyumu, Gazi Osman Paşa ve Dönemi 3 bildiriler, 05-07 Nisan 2000 = The First international Symposium of the Hero of Plevna (1833-1900) Sempozyumu, (1. : Gazi Osman Pasa and His Period (1833-1900), papers, 05-07 April 2000 2004 : Tokat 1. Uluslararası Plevne Kahramanı Gazi Osman Paşa ve Dönemi (1833-1900) Uluslararası Plevne Kahramanı Sempozyumu, Gazi Osman Paşa ve Dönemi 4 bildiriler, 05-07 Nisan 2000 = The First international Symposium of the Hero of Plevna (1833-1900) Sempozyumu, (1. : Gazi Osman Pasa and His Period (1833-1900), papers, 05-07 April 2000 2004 : Tokat 5 1 Mart vakası: Irak tezkeresi ve sonrası Bölükbaşı, Deniz 6 100 konuda Avrupa Birliğinin günlük hayatımıza etkileri 7 100 Konuda Avrupa Birliği’nin günlük hayatımıza etkileri 8 100 Konuda Avrupa Birliği’nin günlük hayatımıza etkileri 9 100 konuda Avrupa Birliğinin günlük hayatımıza etkileri 10 12 Eylül: Özal ekonomisinin perde arkası Çölaşan, Emin 11 12 Eylül ve şeriat Mumcu, Uğur 12 12 Mart: ihtilalin pençesinde demokrasi Birand, Mehmet Ali 13 12 Mart anıları Erim, Nihat 14 12’ye 5 kala Türkiye Mümtaz, Hüseyin 15 15 soruda Avrupa Birliği Avrupa Birliği Tek Sigorta Piyasası 16 1878 Cyprus dispute & the Ottoman-British agreement: handover of the island to EnglandUçarol, Rifat 17 1919'un şifresi: (gizli ABD işgalinin belge ve fotoğrafları) Cevizoğlu, M. -

Taking a Stand? Debating the Bauhaus and Modernism, Heidelberg: Arthistoricum.Net 2021, P

The Myth of the White Bauhaus City Tel Aviv Philipp Oswalt Oswalt, Philipp, The Myth of the White Bauhaus City Tel Aviv, in: Bärnreuther, Andrea (ed.), Taking a Stand? Debating the Bauhaus and Modernism, Heidelberg: arthistoricum.net 2021, p. 397-408, https://doi.org/10.11588/arthistoricum.843.c112922 Fig. 1 Cover of the catalogue for the exhibition «White City. International Style Architecture in Israel. A Portrait of an Era», in the Tel Aviv Museum, 1984, by Michael D. Levin. (Cover picture: Leopold Krakauer, Bendori House (Teltch Hotel), 103 Derech Hayam, Haifa, 1934–35) 399 Philipp Oswalt tel aviv as bauhaus’ world capital No newspaper supplement today can fail to mention Tel Aviv as a «bauhaus» white city «Bauhaus city». Scarcely anywhere seems better suited to illustrat- social relevance of the bauhaus ing the Bauhaus’ social relevance and impact. At the same time, al- most nowhere else demonstrates more impressively how the myths bauhaus brand surrounding the Bauhaus brand have become detached from his- bauhaus myths torical realities and taken on an independent existence. The White City is anything but a genuine Bauhaus city.1 In terms of those involved, it is only marginally connected with the questioning bauhaus brand’s Bauhaus: Over two hundred architects worked in Tel Aviv in the «bauhaus» constructions 1930s, but only four of these had studied at the Bauhaus for some time.2 The percentage of Bauhaus students involved in planning Auschwitz was higher: From 1940 to 1943, Bauhaus alumnus Fritz questioning entrenched Ertl was -

Modernism and Fascism in Norway by Dean N. Krouk A

Catastrophes of Redemption: Modernism and Fascism in Norway By Dean N. Krouk A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Scandinavian in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Mark Sandberg, Chair Professor Linda Rugg Professor Karin Sanders Professor Dorothy Hale Spring 2011 Abstract Catastrophes of Redemption: Modernism and Fascism in Norway by Dean N. Krouk Doctor of Philosophy in Scandinavian University of California, Berkeley Professor Mark Sandberg, Chair This study examines selections from the work of three modernist writers who also supported Norwegian fascism and the Nazi occupation of Norway: Knut Hamsun (1859- 1952), winner of the 1920 Nobel Prize; Rolf Jacobsen (1907-1994), Norway’s major modernist poet; and Åsmund Sveen (1910-1963), a fascinating but forgotten expressionist figure. In literary studies, the connection between fascism and modernism is often associated with writers such as Ezra Pound or Filippo Marinetti. I look to a new national context and some less familiar figures to think through this international issue. Employing critical models from both literary and historical scholarship in modernist and fascist studies, I examine the unique and troubling intersection of aesthetics and politics presented by each figure. After establishing a conceptual framework in the first chapter, “Unsettling Modernity,” I devote a separate chapter to each author. Analyzing both literary publications and lesser-known documents, I describe how Hamsun’s early modernist fiction carnivalizes literary realism and bourgeois liberalism; how Sveen’s mystical and queer erotic vitalism overlapped with aspects of fascist discourse; and how Jacobsen imagined fascism as way to overcome modernity’s culture of nihilism. -

Modernism Revisited Edited by Aleš Erjavec & Tyrus Miller XXXV | 2/2014

Filozofski vestnik Modernism Revisited Edited by Aleš Erjavec & Tyrus Miller XXXV | 2/2014 Izdaja | Published by Filozofski inštitut ZRC SAZU Institute of Philosophy at SRC SASA Ljubljana 2014 CIP - Kataložni zapis o publikaciji Narodna in univerzitetna knjižnica, Ljubljana 141.7(082) 7.036(082) MODERNISM revisited / edited by Aleš Erjavec & Tyrus Miller. - Ljubljana : Filozofski inštitut ZRC SAZU = Institute of Philosophy at SRC SASA, 2014. - (Filozofski vestnik, ISSN 0353-4510 ; 2014, 2) ISBN 978-961-254-743-1 1. Erjavec, Aleš, 1951- 276483072 Contents Filozofski vestnik Modernism Revisited Volume XXXV | Number 2 | 2014 9 Aleš Erjavec & Tyrus Miller Editorial 13 Sascha Bru The Genealogy-Complex. History Beyond the Avant-Garde Myth of Originality 29 Eva Forgács Modernism's Lost Future 47 Jožef Muhovič Modernism as the Mobilization and Critical Period of Secular Metaphysics. The Case of Fine/Plastic Art 67 Krzysztof Ziarek The Avant-Garde and the End of Art 83 Tyrus Miller The Historical Project of “Modernism”: Manfredo Tafuri’s Metahistory of the Avant-Garde 103 Miško Šuvaković Theories of Modernism. Politics of Time and Space 121 Ian McLean Modernism Without Borders 141 Peng Feng Modernism in China: Too Early and Too Late 157 Aleš Erjavec Beat the Whites with the Red Wedge 175 Patrick Flores Speculations on the “International” Via the Philippine 193 Kimmo Sarje The Rational Modernism of Sigurd Fosterus. A Nordic Interpretation 219 Ernest Ženko Ingmar Bergman’s Persona as a Modernist Example of Media Determinism 239 Rainer Winter The Politics of Aesthetics in the Work of Michelangelo Antonioni: An Analysis Following Jacques Rancière 255 Ernst van Alphen On the Possibility and Impossibility of Modernist Cinema: Péter Forgács’ Own Death 271 Terry Smith Rethinking Modernism and Modernity 321 Notes on Contributors 325 Abstracts Kazalo Filozofski vestnik Ponovno obiskani modernizem Letnik XXXV | Številka 2 | 2014 9 Aleš Erjavec & Tyrus Miller Uvodnik 13 Sascha Bru Genealoški kompleks. -

Fascism's Modernist Revolution: a New Paradigm for the Study Of

fascism 5 (2016) 105-129 brill.com/fasc Fascism’s Modernist Revolution: A New Paradigm for the Study of Right-wing Dictatorships Roger Griffin Oxford Brookes University [email protected] Abstract This article highlights the progress that has been made within fascist studies from see- ing ‘fascist culture’ as an oxymoron, and assuming that it was driven by a profound animus against modernity and aesthetic modernism, to wide acceptance that it had its own revolutionary dynamic as a search for a Third Way between liberalism and commu- nism, and bid to establish an alternative, rooted modern culture. Building logically on this growing consensus, the next stage is to a) accept that modernism is legitimately ex- tended to apply to radical experimentation in society, economics, politics, and material culture; b) realize that seen from this perspective each fascism was proposing its own variant of modernism in both a socio-political and aesthetic sense, and that c) right-wing regimes influenced by fascism produced their own experiments in developing both a modern political regime and cultural modernism grounded in a unique national history. Keywords fascism – modernism – fascist studies – dictatorship … Eventually one of the new points of view triumphs by solving some of the problems posed by the anomalies. It will probably not solve all of the * This article is a modified version of the English original of ‘La revolución modernista del fascismo: un nuevo paradigma para el estudio de las dictaduras de derechos,’ in Fascismo y modernism: Política y cultura en la Europa de entreguerras (1919–1945), ed. Francisco Cobo, Miguel Á. -

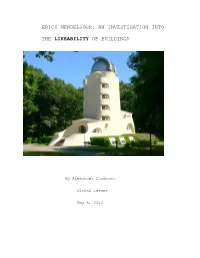

Erich Mendelsohn: an Investigation Into

ERICH MENDELSOHN: AN INVESTIGATION INTO THE LIKEABILITY OF BUILDINGS By Alexander Luckmann Global Issues May 6, 2013 Abstract In my paper, I attempted to answer a central questions about architecture: what makes certain buildings create such a strong sense of belonging and what makes others so sterile and unwelcoming. I used the work of German-born architect Erich Mendelsohn to help articulate solutions to these questions, and to propose paths of exploration for a kinder and more place-specific architecture, by analyzing the success of many of Mendelsohn’s buildings both in relation to their context and in relation to their emotional effect on the viewer/user, and by comparing this success with his less successful buildings. I compared his early masterpiece, the Einstein Tower, with a late work, the Emanue-El Community Center, to investigate this difference. I attempted to place Mendelsohn in his architectural context. I was sitting on the roof of the apartment of a friend of my mother’s in Constance, Germany, a large town or a small city, depending on one’s reference point. The apartment, where I had been frequently up until perhaps the age of six but hadn’t visited recently, is on the top floor of an old building in the city center, dating from perhaps the sixteenth or seventeenth centuries. The rooms are fairly small, but they are filled with light, and look out over the bustling downtown streets onto other quite similar buildings. Almost all these buildings have stores on the ground floor, often masking their beauty to those who don’t look up (whatever one may say about modern stores, especially chain stores, they have done a remarkable job of uglifying the street at ground level).