Michele Stavagna Berlin/Triest

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2019 01 17 Draft TP JF

‘Sensation of space and modern architecture’ : a psychology of architecture by Franz Löwitsch Poppelreuter, T http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13602365.2012.678645 Title ‘Sensation of space and modern architecture’ : a psychology of architecture by Franz Löwitsch Authors Poppelreuter, T Type Article URL This version is available at: http://usir.salford.ac.uk/id/eprint/46929/ Published Date 2012 USIR is a digital collection of the research output of the University of Salford. Where copyright permits, full text material held in the repository is made freely available online and can be read, downloaded and copied for non-commercial private study or research purposes. Please check the manuscript for any further copyright restrictions. For more information, including our policy and submission procedure, please contact the Repository Team at: [email protected]. Sensation of Space and Modern Architecture A psychology of architecture by Franz Löwitsch Abstract: In 1928 the Austrian architect and engineer Franz Löwitsch (1894-1946) published the article “Sensation of Space and Modern Architecture” in Imago, the psychoanalytical journal edited by Sigmund Freud. Based on Richard Semon’s theories of Mneme, which Löwitsch connected to psychoanalytical theories, the prevalence of dissimilar sensations of space throughout the stages of the development of western architectural history is presupposed, and Löwitsch offered an explanation of how their symbolic meanings reflected psychological conditions of a particular time and culture. By connecting Semon’s theory with psychoanalytical deliberations that equip the inherited memory of spatial sensations with pleasurable or unpleasurable emotions, Löwitsch furthermore argued that spatial sensations produce spatial concepts, and that the dominating shapes and forms of the architecture of a time therefore reflect the dominance of a particular inherited sensation of space. -

CHAPTER 2 the Period of the Weimar Republic Is Divided Into Three

CHAPTER 2 BERLIN DURING THE WEIMAR REPUBLIC The period of the Weimar Republic is divided into three periods, 1918 to 1923, 1924 to 1929, and 1930 to 1933, but we usually associate Weimar culture with the middle period when the post WWI revolutionary chaos had settled down and before the Nazis made their aggressive claim for power. This second period of the Weimar Republic after 1924 is considered Berlin’s most prosperous period, and is often referred to as the “Golden Twenties”. They were exciting and extremely vibrant years in the history of Berlin, as a sophisticated and innovative culture developed including architecture and design, literature, film, painting, music, criticism, philosophy, psychology, and fashion. For a short time Berlin seemed to be the center of European creativity where cinema was making huge technical and artistic strides. Like a firework display, Berlin was burning off all its energy in those five short years. A literary walk through Berlin during the Weimar period begins at the Kurfürstendamm, Berlin’s new part that came into its prime during the Weimar period. Large new movie theaters were built across from the Kaiser Wilhelm Memorial church, the Capitol und Ufa-Palast, and many new cafés made the Kurfürstendamm into Berlin’s avant-garde boulevard. Max Reinhardt’s theater became a major attraction along with bars, nightclubs, wine restaurants, Russian tearooms and dance halls, providing a hangout for Weimar’s young writers. But Berlin’s Kurfürstendamm is mostly famous for its revered literary cafés, Kranzler, Schwanecke and the most renowned, the Romanische Café in the impressive looking Romanische Haus across from the Memorial church. -

Nurses and Midwives in Nazi Germany

Downloaded by [New York University] at 03:18 04 October 2016 Nurses and Midwives in Nazi Germany This book is about the ethics of nursing and midwifery, and how these were abrogated during the Nazi era. Nurses and midwives actively killed their patients, many of whom were disabled children and infants and patients with mental (and other) illnesses or intellectual disabilities. The book gives the facts as well as theoretical perspectives as a lens through which these crimes can be viewed. It also provides a way to teach this history to nursing and midwifery students, and, for the first time, explains the role of one of the world’s most historically prominent midwifery leaders in the Nazi crimes. Downloaded by [New York University] at 03:18 04 October 2016 Susan Benedict is Professor of Nursing, Director of Global Health, and Co- Director of the Campus-Wide Ethics Program at the University of Texas Health Science Center School of Nursing in Houston. Linda Shields is Professor of Nursing—Tropical Health at James Cook Uni- versity, Townsville, Queensland, and Honorary Professor, School of Medi- cine, The University of Queensland. Routledge Studies in Modern European History 1 Facing Fascism 9 The Russian Revolution of 1905 The Conservative Party and the Centenary Perspectives European dictators 1935–1940 Edited by Anthony Heywood and Nick Crowson Jonathan D. Smele 2 French Foreign and Defence 10 Weimar Cities Policy, 1918–1940 The Challenge of Urban The Decline and Fall of a Great Modernity in Germany Power John Bingham Edited by Robert Boyce 11 The Nazi Party and the German 3 Britain and the Problem of Foreign Office International Disarmament Hans-Adolf Jacobsen and Arthur 1919–1934 L. -

Potsdamer Platz

Potsdamer Platz Der Potsdamer Platz ist ein Verkehrsknoten im Berliner Ortsteil Tiergarten im Bezirk Mitte zwischen der alten In- nenstadt im Osten und dem neuen Berliner Westen. Er schließt sich westlich an den Leipziger Platz an und liegt an der Stelle des ehemaligen Potsdamer Stadttors vor der Akzisemauer. Bis zum Zweiten Weltkrieg war der noch als Platz zu erle- bende Ort ein beliebter Treffpunkt der politischen, sozialen und künstlerischen Szene Berlins. Das nach 1990 auf dem alten Stadtgrundriss größtenteils neu bebaute Terrain zählt zu den markantesten Orten der Stadt und wird von zahlreichen Touristen besucht. Potsdamer-Platz Lustaufnahme Geschichte Anfang des 18. Jahrhunderts lag der Potsdamer Platz un- mittelbar vor der Stadtmauer am Potsdamer Tor. Er hatte die Funktion eines Verkehrsverteilers, da alle Straßen aus dem Westen und Südwesten auf das Tor zuliefen, und stellte eine fünfarmige Straßenkreuzung dar, aus der sich schnell ein Verkehrsknotenpunkt an der alten Reichsstraße 1 entwickelte, die Ostpreußen mit dem Rheinland verband. In den Jahren 1823 und 1824 wurde das zwischen Pots- damer und Leipziger Platz liegende Stadttor Richtung Potsdam (Leipziger Tor oder auch Potsdamer Tor ge- nannt) von dem königlichen Baumeister Karl Friedrich Schinkel baulich ausgestaltet. Die von ihm gestalteten Torhäuschen (die so genannten Schinkel) des Neuen Potsdamer Thores blieben auch nach dem Abriss der Akzise- Leipziger Tor mauer 1867 stehen und prägten mit ihrer klassizistischen Architektur den Platz bis zum Ende des Zweiten Weltkriegs. Durch die Errichtung des Potsdamer Fern- bahnhofs im Jahr 1838 wandelte sich der Cha- rakter des nahe dem alten Berliner Zentrum gelegenen Platzes Zug um Zug zu einem großstädtischen Umschlagplatz für Menschen und Waren. -

Enchanted Catastrophe

ENCHANTED CATASTROPHE What an amazing country where the houses are taller than churches —FERNAND LÉGER AFTER VISITING THE UNITED STATES FOR THE FIRST TIME IN 19311 “What is this new religion?” he wondered, and then concluded: “It’s Wall Street that dominates this new world with all of its height.”1 Léger’s astonishment may seem dated today, when luxury high-rises and tall office buildings have come to appear more banal than transcendent, and stands in contrast to the more sensationalistic response of his friend Le Corbusier, who quipped that New York’s skyscrapers were “too small” when he visited the city four years later. Yet his ultimate point remains remarkably acute: “the vertical push is in line with the economic order.”2 For in contrast to the traditional image of the religious spire, the capitalist transformation of the tall tower typology has come to represent the Americanization of metropolitan modernity, and although ostensibly secular, it continues to be mystified to this day. The skyscraper is more than just a symbolic icon of capitalist power, however, for as Carol Willis argues in her study Form Follows Finance, it is also direct index of financial investment and real estate speculation.3 Léger apparently recognized this not long after the stock market crash of 1929 when he wrote: “Wall Street has gone too far in transforming everything into speculation. Wall Street is an amazing abstraction, but catastrophic. American vertical architecture has gone too far….”4 1. Fernand Léger, “New York,” in Fonctions de la peinture (Paris: Editions Gallimard, 2004), 152-3. -

The Critical Dimension of German Department Stores

84THACSAANNUALMEETlNG HISTORY 1996 21 5 From Messel to Mendelsohn: The Critical Dimension of German Department Stores KATHLEEN JAMES University of California, Berkeley INTRODUCTION favor of a reassuring image of historical and social continu- ity, Mendelsohn used advertising to dress up the austere The dilemma faced by many architects today of how to industrial imagery that epitomized his rejection of conven- practice within a consumer culture with which they are not tional luxury. Although conditioned in part by the individual entirely comfortable is not a new one, although the variety taste of the two architects and the different character of the of ways that earlier architects addressed it has often been department store chains who employed them, many of these overlooked in accounts that privilege style, theory, and differences are mirrored in the writings of two generations of construction over issues of use. Furthermore, the common German architecturai critics, whose attitudes toward con- assumption that the work of the heroic figures of the modem sumerism changed dramatically after World War I. movement provide an alternative to such commercialism Both Messel and Mendelsohn excelled at giving orderly, often alienates us from what we often perceive to be a new, but interesting form to urban building types (office and specifically postmodern condition. By delineating the ways apartment buildings) more typically associated with the in which two generations of German architects addressed most chaotic aspects of contemporary real estate specula- their concerns about the department store, this paper pro- tion. Each architect also managed to downplay the aspects vides some measure of precedent for an architecture which of commercialism that most distressed him and his contem- does in part critique its apparent program, while exposing the poraries while satisfying his patron's needs for environments enthusiasm for the consumer face of mass production that suitable to selling. -

Weimar Germany Still Speaks to Us

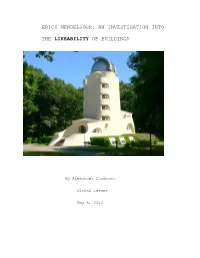

© Copyright, Princeton University Press. No part of this book may be distributed, posted, or reproduced in any form by digital or mechanical means without prior written permission of the publisher. INTRODUCTION Weimar Germany still speaks to us. Paintings by George Grosz and Max Beckmann are much in demand and hang in muse- ums and galleries from Sydney to Los Angeles to St. Petersburg. Bertolt Brecht and Kurt Weill’s The Threepenny Opera is periodically revived in theaters around the world and in many different lan- guages. Thomas Mann’s great novel The Magic Mountain, first pub- lished in 1925, remains in print and, if not exactly a household item, is read and discussed in literature and philosophy classes at count- less colleges and universities. Contemporary kitchen designs invoke the styles of the 1920s and the creative work of the Bauhaus. Post- modern architects may have abandoned the strict functionalism of Walter Gropius, but who can resist the beauty of Erich Mendelsohn’s Columbus House or his Schocken department stores (only one of which is still standing), with their combination of clean lines and dynamic movement, or the whimsy of his Einstein Tower? Hannah Höch might not be as widely known as these others, but viewers who encounter her work today are drawn to her inventive combination of primitivist and modernist styles, her juxtaposition of African or Polynesian-style masks with the everyday objects of the 1920s. The deep philosophical speculations of Martin Heidegger and the layered essays of Siegfried Kracauer, both grappling with the meaning of ad- vanced technology and mass society, still offer a wealth of insight into the modern condition. -

The Einstein Tower, Potsdam, Germany

Case Study 12.5: The Einstein Tower, Potsdam, Germany Gudrun Wolfschmidt and Michel Cotte Presentation and analysis of the site Geographical position: Telegrafenberg 1 , 14473 Potsdam, Germany. Location : Latitude 52º 22´ 44˝ N, longitude 13º 3´ 50 E˝. Elevation 87m above mean sea level. General description: The Einstein Tower, designed by the Berlin architect Erich Mendelsohn (1857–1953) and built in the early 1920s, is both an astrophysical observatory and a masterpiece of the history of modern architecture in Germany. Brief inventory : • The tower itself is 20m high. It was constructed between 1920 and 1922, but owing to a lack of modern construction materials after World War I, the tower had to be built with bricks instead of reinforced concrete. As a protection against the wind and heating, a wood- en structure was added on the inside of the tower, and this supports the objective lens. • The instrumentation was installed in 1924. The dome is 4.5 m in diameter and contained the two 85 cm-coelostat mirrors. The lens of 60 cm aperture and 14.50 m focal length produced a solar image 14 cm in diameter. The company Zeiss of Jena was responsible for the instrumentation. • The cellar contained a room at constant temperature. Here, two high-resolution spectrographs produced solar spectra from red to violet with a length of 12 m. In 1925, a physical-spectrographic laboratory was constructed. This contained a spectral furnace as a comparison light source, an apparatus to produce an electric arc, a photoelectric Registration photometer, an electromagnet and an apparatus for the investigation of the hyperfine structure of emission lines. -

Taking a Stand? Debating the Bauhaus and Modernism, Heidelberg: Arthistoricum.Net 2021, P

The Myth of the White Bauhaus City Tel Aviv Philipp Oswalt Oswalt, Philipp, The Myth of the White Bauhaus City Tel Aviv, in: Bärnreuther, Andrea (ed.), Taking a Stand? Debating the Bauhaus and Modernism, Heidelberg: arthistoricum.net 2021, p. 397-408, https://doi.org/10.11588/arthistoricum.843.c112922 Fig. 1 Cover of the catalogue for the exhibition «White City. International Style Architecture in Israel. A Portrait of an Era», in the Tel Aviv Museum, 1984, by Michael D. Levin. (Cover picture: Leopold Krakauer, Bendori House (Teltch Hotel), 103 Derech Hayam, Haifa, 1934–35) 399 Philipp Oswalt tel aviv as bauhaus’ world capital No newspaper supplement today can fail to mention Tel Aviv as a «bauhaus» white city «Bauhaus city». Scarcely anywhere seems better suited to illustrat- social relevance of the bauhaus ing the Bauhaus’ social relevance and impact. At the same time, al- most nowhere else demonstrates more impressively how the myths bauhaus brand surrounding the Bauhaus brand have become detached from his- bauhaus myths torical realities and taken on an independent existence. The White City is anything but a genuine Bauhaus city.1 In terms of those involved, it is only marginally connected with the questioning bauhaus brand’s Bauhaus: Over two hundred architects worked in Tel Aviv in the «bauhaus» constructions 1930s, but only four of these had studied at the Bauhaus for some time.2 The percentage of Bauhaus students involved in planning Auschwitz was higher: From 1940 to 1943, Bauhaus alumnus Fritz questioning entrenched Ertl was -

DOKUMENTE Projekt „17. Juni 1953“ 1

DOKUMENTE Projekt „17. Juni 1953“ 1 [Der Polizeipräsident in Berlin] MELDUNGEN ANLÄßLICH DER DEMONSTRATIONEN IM OSTSEKTOR AM 17.6.1953 08.25 Uhr R. 28, Wm. Sch.: 12 Lkw. und 2 kl. Mannschaftswagen, besetzt mit Volkspolizei in blauer Uniform, von Richtung Unter den Linden kommend in Wilhelmstr. eingebogen und Richtung Leipziger Str. weitergefahren. Ein Lkw. mit Russen steht vor der russ. Botschaft am Pariser Platz. (BS B. 08.38, S. D. 08.40) 08.45 Uhr Hw. H., R. 29/30: Ein Demonstrationszug bewegt sich Leipziger Str. in Richtung Wilhelmstr. Russen sollen mit Panzerspähwagen aufgefahren sein. 08.45 Uhr R. 28, Ow. K.: 1.) Nördl. des Brandenburger Tors ist die Vopo.-Polizeiwache mit ca. 30 VP-Offizieren besetzt. 2.) Nach Angaben von Zivilpersonen wurden die Ruinen gegenüber der russ. Botschaft mit russ. Soldaten besetzt. Bewaffnung: MP und 3 MG. 3.) Wiederholt kreuzen ca. 10 Panzerspähwagen in Nähe der russ. Botschaft auf. (BS B. 09.04, S Sch. 09.06) 08.48 Uhr R. 29/30, Hw. H.: Zivilperson meldet, daß am Strausberger Platz Russen schießen sollen. (BS u. S. durch O.I. Sch. gemeldet.) 09.10 Uhr R. 28, Straßenmelder Charlbg. Chaussee: Aus Richtung ehem. Reichskanz- lei starke Rauchentwicklung. (S Sch. 09.15 Uhr, BS B. 09.17 Uhr) 09.15 Uhr Melder Brandenburger Tor: Demonstrationszug (Stärke ca. 1.000 Personen) soeben durch Brandenburger Tor marschiert und bewegt sich Friedrich- Ebert-Str. in Richtung Potsdamer Platz. (S K. 09.24, BS B. 09.28) 09.22 Uhr Lehrter-Bhf.-Wache, Wm. Sch.: Von der Scharnhorststr. bis zur Sekt.Grenze (Sandkrugbrücke) patroullieren 2 Vopo. -

Berliner Straßenleben Um 1910 (Avt) (Ca.1910) ...P.P

Potsdamer Platz Bitte beachten Sie, dass zu den ab Seite 5 genannten Filmtiteln im Bundesarchiv kein benutzbares Material vorliegt. Gern können Sie unter [email protected] erfragen, ob eine Nutzung mittlerweile möglich ist. - Berliner Straßenleben um 1910 (AvT) (ca.1910) ...P.P. mit fließendem Verkehr. - Berlin in der Weihnachtswoche (AvT) (ca. 1912) ...Verkehrspolizist am P.P. - Bilder aus Alt-Berlin (1912) ... Verkehr in Berlin. Verkehr am Potsdamer Platz. (R.2) - Rentier Kulicke's Flug zur Front (1918) ... Flug über den Gendarmenmarkt und den Potsdamer Platz - Kapitänleutnant von Mücke; Feldmarschall von Hindenburg und Rittmeister von Pentz (1915) ...Empfangskomitee aus Damen und Herren vor dem Eingang des "Hotel Fürstenhof " am Potsdamer Platz in Berlin am 20.06.1915; Überreichen eines Blumenstraußes an von Mücke durch eine Ehrenjungfrau, Hüteschwenken, von Mücke grüßend, mit seiner Mutter Louise von Mücke vom Hoteleingang durch die winkende Menge sich zu einem Pkw begebend, aus dem Pkw zeitweise im Stehen grüßend. - Messter-Woche Nr. 16 + 17/1920 (1920) ...Berlin: Der Kammersänger Julius Lieban gründete mit seinem Bruder Adalbert Lieban die Kleinkunst-Bühne am Potsdamer Platz - Berliner Erinnerungen (1918 - 1933) (1955) ...Verkehr am P.P. um 1920 - Die Geburt des Reichsrundfunk in Berlin im Jahre 1923 ...Berlin Potsdamer Platz (nicht aus 1923 sondern später, da bereits der Verkehrsturm steht) Blick auf Bellevuestraße und Potsdamer-Straße, starker Straßenbahn u.a. Verkehr - Mit dem Auto ins Morgenland (1925) ...Ufa-Palast am Potsdamer Platz in Berlin, U-Bahn Eingang Potsdamer Platz, Verkehr und Fußgänger. - Deulig-Woche 1925 (1925) - Die Stadt der Millionen (1925) ...P.P. (R.3 und 6) - Im Strudel des Verkehrs (1925) - Phoebus-Opel-Woche 28/1926 - Berlin 1927 II ...Verkehr am P.P. -

Erich Mendelsohn: an Investigation Into

ERICH MENDELSOHN: AN INVESTIGATION INTO THE LIKEABILITY OF BUILDINGS By Alexander Luckmann Global Issues May 6, 2013 Abstract In my paper, I attempted to answer a central questions about architecture: what makes certain buildings create such a strong sense of belonging and what makes others so sterile and unwelcoming. I used the work of German-born architect Erich Mendelsohn to help articulate solutions to these questions, and to propose paths of exploration for a kinder and more place-specific architecture, by analyzing the success of many of Mendelsohn’s buildings both in relation to their context and in relation to their emotional effect on the viewer/user, and by comparing this success with his less successful buildings. I compared his early masterpiece, the Einstein Tower, with a late work, the Emanue-El Community Center, to investigate this difference. I attempted to place Mendelsohn in his architectural context. I was sitting on the roof of the apartment of a friend of my mother’s in Constance, Germany, a large town or a small city, depending on one’s reference point. The apartment, where I had been frequently up until perhaps the age of six but hadn’t visited recently, is on the top floor of an old building in the city center, dating from perhaps the sixteenth or seventeenth centuries. The rooms are fairly small, but they are filled with light, and look out over the bustling downtown streets onto other quite similar buildings. Almost all these buildings have stores on the ground floor, often masking their beauty to those who don’t look up (whatever one may say about modern stores, especially chain stores, they have done a remarkable job of uglifying the street at ground level).