Taking a Stand? Debating the Bauhaus and Modernism, Heidelberg: Arthistoricum.Net 2021, P

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Land of Israel Symbolizes a Union Between the Most Modern Civilization and a Most Antique Culture. It Is the Place Where

The Land of Israel symbolizes a union between the most modern civilization and a most antique culture. It is the place where intellect and vision, matter and spirit meet. Erich Mendelsohn The Weizmann Institute of Science is one of Research by Institute scientists has led to the develop- the world’s leading multidisciplinary basic research ment and production of Israel’s first ethical (original) drug; institutions in the natural and exact sciences. The the solving of three-dimensional structures of a number of Institute’s five faculties – Mathematics and Computer biological molecules, including one that plays a key role in Science, Physics, Chemistry, Biochemistry and Biology Alzheimer’s disease; inventions in the field of optics that – are home to 2,600 scientists, graduate students, have become the basis of virtual head displays for pilots researchers and administrative staff. and surgeons; the discovery and identification of genes that are involved in various diseases; advanced techniques The Daniel Sieff Research Institute, as the Weizmann for transplanting tissues; and the creation of a nanobiologi- Institute was originally called, was founded in 1934 by cal computer that may, in the future, be able to act directly Israel and Rebecca Sieff of the U.K., in memory of their inside the body to identify disease and eliminate it. son. The driving force behind its establishment was the Institute’s first president, Dr. Chaim Weizmann, a Today, the Institute is a leading force in advancing sci- noted chemist who headed the Zionist movement for ence education in all parts of society. Programs offered years and later became the first president of Israel. -

Tel Aviv Elite Guide to Tel Aviv

DESTINATION GUIDE SERIES TEL AVIV ELITE GUIDE TO TEL AVIV HIGHLIGHTS OF TEL AVIV 3 ONLY ELITE 4 Elite Traveler has selected an exclusive VIP experience EXPERT RECOMMENDATIONS 5 We asked top local experts to share their personal recommendations ENJOY ELEGANT SEA-FACING LUXURY AT THE CARLTON for the perfect day in Tel Aviv WHERE TO ➤ STAY 7 ➤ DINE 13 ➤ BE PAMPERED 16 RELAX IN STYLE AT THE BEACH WHAT TO DO ➤ DURING THE DAY 17 ➤ DURING THE NIGHT 19 ➤ FEATURED EVENTS 21 ➤ SHOPPING 22 TASTE SUMPTUOUS GOURMET FLAVORS AT YOEZER WINE BAR NEED TO KNOW ➤ MARINAS 25 ➤ PRIVATE JET TERMINALS 26 ➤ EXCLUSIVE TRANSPORT 27 ➤ USEFUL INFORMATION 28 DISCOVER CUTTING EDGE DESIGNER STYLE AT RONEN ChEN (C) ShAI NEIBURG DESTINATION GUIDE SERIES ELITE DESTINATION GUIDE | TEL AVIV www.elitetraveler.com 2 HIGHLIGHTS OF TEL AVIV Don’t miss out on the wealth of attractions, adventures and experiences on offer in ‘The Miami of the Middle East’ el Aviv is arguably the most unique ‘Habuah’ (‘The Bubble’), for its carefree Central Tel Aviv’s striking early 20th T city in Israel and one that fascinates, and fun-loving atmosphere, in which century Bauhaus architecture, dubbed bewilders and mesmerizes visitors. the difficult politics of the region rarely ‘the White City’, is not instantly Built a mere century ago on inhospitable intrudes and art, fashion, nightlife and attractive, but has made the city a World sand dunes, the city has risen to become beach fun prevail. This relaxed, open vibe Heritage Site, and its golden beaches, a thriving economic hub, and a center has seen Tel Aviv named ‘the gay capital lapped by the clear azure Mediterranean, of scientific, technological and artistic of the Middle East’ by Out Magazine, are beautiful places for beautiful people. -

Enchanted Catastrophe

ENCHANTED CATASTROPHE What an amazing country where the houses are taller than churches —FERNAND LÉGER AFTER VISITING THE UNITED STATES FOR THE FIRST TIME IN 19311 “What is this new religion?” he wondered, and then concluded: “It’s Wall Street that dominates this new world with all of its height.”1 Léger’s astonishment may seem dated today, when luxury high-rises and tall office buildings have come to appear more banal than transcendent, and stands in contrast to the more sensationalistic response of his friend Le Corbusier, who quipped that New York’s skyscrapers were “too small” when he visited the city four years later. Yet his ultimate point remains remarkably acute: “the vertical push is in line with the economic order.”2 For in contrast to the traditional image of the religious spire, the capitalist transformation of the tall tower typology has come to represent the Americanization of metropolitan modernity, and although ostensibly secular, it continues to be mystified to this day. The skyscraper is more than just a symbolic icon of capitalist power, however, for as Carol Willis argues in her study Form Follows Finance, it is also direct index of financial investment and real estate speculation.3 Léger apparently recognized this not long after the stock market crash of 1929 when he wrote: “Wall Street has gone too far in transforming everything into speculation. Wall Street is an amazing abstraction, but catastrophic. American vertical architecture has gone too far….”4 1. Fernand Léger, “New York,” in Fonctions de la peinture (Paris: Editions Gallimard, 2004), 152-3. -

The Critical Dimension of German Department Stores

84THACSAANNUALMEETlNG HISTORY 1996 21 5 From Messel to Mendelsohn: The Critical Dimension of German Department Stores KATHLEEN JAMES University of California, Berkeley INTRODUCTION favor of a reassuring image of historical and social continu- ity, Mendelsohn used advertising to dress up the austere The dilemma faced by many architects today of how to industrial imagery that epitomized his rejection of conven- practice within a consumer culture with which they are not tional luxury. Although conditioned in part by the individual entirely comfortable is not a new one, although the variety taste of the two architects and the different character of the of ways that earlier architects addressed it has often been department store chains who employed them, many of these overlooked in accounts that privilege style, theory, and differences are mirrored in the writings of two generations of construction over issues of use. Furthermore, the common German architecturai critics, whose attitudes toward con- assumption that the work of the heroic figures of the modem sumerism changed dramatically after World War I. movement provide an alternative to such commercialism Both Messel and Mendelsohn excelled at giving orderly, often alienates us from what we often perceive to be a new, but interesting form to urban building types (office and specifically postmodern condition. By delineating the ways apartment buildings) more typically associated with the in which two generations of German architects addressed most chaotic aspects of contemporary real estate specula- their concerns about the department store, this paper pro- tion. Each architect also managed to downplay the aspects vides some measure of precedent for an architecture which of commercialism that most distressed him and his contem- does in part critique its apparent program, while exposing the poraries while satisfying his patron's needs for environments enthusiasm for the consumer face of mass production that suitable to selling. -

Weimar Germany Still Speaks to Us

© Copyright, Princeton University Press. No part of this book may be distributed, posted, or reproduced in any form by digital or mechanical means without prior written permission of the publisher. INTRODUCTION Weimar Germany still speaks to us. Paintings by George Grosz and Max Beckmann are much in demand and hang in muse- ums and galleries from Sydney to Los Angeles to St. Petersburg. Bertolt Brecht and Kurt Weill’s The Threepenny Opera is periodically revived in theaters around the world and in many different lan- guages. Thomas Mann’s great novel The Magic Mountain, first pub- lished in 1925, remains in print and, if not exactly a household item, is read and discussed in literature and philosophy classes at count- less colleges and universities. Contemporary kitchen designs invoke the styles of the 1920s and the creative work of the Bauhaus. Post- modern architects may have abandoned the strict functionalism of Walter Gropius, but who can resist the beauty of Erich Mendelsohn’s Columbus House or his Schocken department stores (only one of which is still standing), with their combination of clean lines and dynamic movement, or the whimsy of his Einstein Tower? Hannah Höch might not be as widely known as these others, but viewers who encounter her work today are drawn to her inventive combination of primitivist and modernist styles, her juxtaposition of African or Polynesian-style masks with the everyday objects of the 1920s. The deep philosophical speculations of Martin Heidegger and the layered essays of Siegfried Kracauer, both grappling with the meaning of ad- vanced technology and mass society, still offer a wealth of insight into the modern condition. -

The Einstein Tower, Potsdam, Germany

Case Study 12.5: The Einstein Tower, Potsdam, Germany Gudrun Wolfschmidt and Michel Cotte Presentation and analysis of the site Geographical position: Telegrafenberg 1 , 14473 Potsdam, Germany. Location : Latitude 52º 22´ 44˝ N, longitude 13º 3´ 50 E˝. Elevation 87m above mean sea level. General description: The Einstein Tower, designed by the Berlin architect Erich Mendelsohn (1857–1953) and built in the early 1920s, is both an astrophysical observatory and a masterpiece of the history of modern architecture in Germany. Brief inventory : • The tower itself is 20m high. It was constructed between 1920 and 1922, but owing to a lack of modern construction materials after World War I, the tower had to be built with bricks instead of reinforced concrete. As a protection against the wind and heating, a wood- en structure was added on the inside of the tower, and this supports the objective lens. • The instrumentation was installed in 1924. The dome is 4.5 m in diameter and contained the two 85 cm-coelostat mirrors. The lens of 60 cm aperture and 14.50 m focal length produced a solar image 14 cm in diameter. The company Zeiss of Jena was responsible for the instrumentation. • The cellar contained a room at constant temperature. Here, two high-resolution spectrographs produced solar spectra from red to violet with a length of 12 m. In 1925, a physical-spectrographic laboratory was constructed. This contained a spectral furnace as a comparison light source, an apparatus to produce an electric arc, a photoelectric Registration photometer, an electromagnet and an apparatus for the investigation of the hyperfine structure of emission lines. -

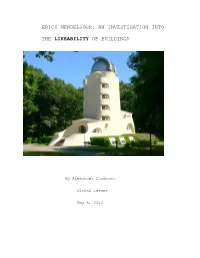

Erich Mendelsohn: an Investigation Into

ERICH MENDELSOHN: AN INVESTIGATION INTO THE LIKEABILITY OF BUILDINGS By Alexander Luckmann Global Issues May 6, 2013 Abstract In my paper, I attempted to answer a central questions about architecture: what makes certain buildings create such a strong sense of belonging and what makes others so sterile and unwelcoming. I used the work of German-born architect Erich Mendelsohn to help articulate solutions to these questions, and to propose paths of exploration for a kinder and more place-specific architecture, by analyzing the success of many of Mendelsohn’s buildings both in relation to their context and in relation to their emotional effect on the viewer/user, and by comparing this success with his less successful buildings. I compared his early masterpiece, the Einstein Tower, with a late work, the Emanue-El Community Center, to investigate this difference. I attempted to place Mendelsohn in his architectural context. I was sitting on the roof of the apartment of a friend of my mother’s in Constance, Germany, a large town or a small city, depending on one’s reference point. The apartment, where I had been frequently up until perhaps the age of six but hadn’t visited recently, is on the top floor of an old building in the city center, dating from perhaps the sixteenth or seventeenth centuries. The rooms are fairly small, but they are filled with light, and look out over the bustling downtown streets onto other quite similar buildings. Almost all these buildings have stores on the ground floor, often masking their beauty to those who don’t look up (whatever one may say about modern stores, especially chain stores, they have done a remarkable job of uglifying the street at ground level). -

Michele Stavagna Berlin/Triest

Michele Stavagna Berlin/Triest Michele Stavagna is an architect and Stavagna translated and edited the first architectural historian, who lives and Italian edition of “Die Baukunst der works in Berlin, and is the correspondent neuesten Zeit” by G. A. Platz. His research from Italy for the magazine “der architekt themes focus on the birth and affirmation - BDA”. He was educated at the Università of Modernism within the broader context IUAV of Venice (Italy), holds a degree in of the mass public and economic develop- architectural design and a PhD in history ment of the modern society. of architecture and urban design, and has taught Theory and History of Industrial Design at the Università degli Studi of Triest (Italy). The Herpich Affair 1924 | Stavagna 460 THE HERPICH AFFAIR OF 1924 Modern Architecture Challenging the Economic Establishment In 1923, Erich Mendelsohn was by far the most successful among the young Ger- man architects, having already realized many important buildings: the Einstein tower, the Steinberg-Herrmann Hat Factory, the renewal of the Mosse Publisher Building. Between 1923 and 1924 he developed the plan for the renewal and ex- pansion of the building for the Herpich Furriers on Leipziger Strasse, which was the most important commercial street in Berlin. The entangled history of the proj- ect approval and realization testifies to a crucial moment for the affirmation of modern architecture. Unfortunately, the official documentation about the Herpich store, including even the building itself, has been lost.1 The first known date regarding this project is revealed in Mendelsohn’s private correspondence to his wife on 7 April 1924. -

Erich Mendelsohn

Erich Mendelsohn (21 March 1887 – 15 September 1953) “Every building material, like every substance, has certain conditions governing the demands that can be made on it….Steel in combination with concrete, reinforced concrete, is the building material for the new formal expression, for the new style… The relation between support and load, this apparently eternal law, will also have to alter its image, for things support themselves which formerly had to be supported…” Erich Mendelsohn, letter to Luise Maas, March 14, 1914 Max Berg, Centennial Hall Breslau, Germany 1913 (now Wroclaw, Poland.) Wassily Kandinsky Max Berg, Centennial Hall Painting with White Border Breslau, Germany 1913 1913 (now Wroclaw, Poland.) Expressionism Marc Franz Wassily Kandinsk Rehe im Walde On White II Umberto Boccioni, Unique Forms of Continuity in Space, 1913 Analogy between a particular industrial technology—reinforced concrete– and the human body Newton’s fixed space Einstein’s flexible space-time Erich Mendelsohn, sketches for the Einstein Tower, Potsdam, Germany 1917 light space time “organic” shift in materials Imagery worked on several levels. It represented the: 1. Truth of reinforced concrete construction in which a steel frame or skeleton supported and stiffened the concrete flesh 2. Stresses shaping the form (the compression and tension of both reinforced concrete and the human body) 3. Intricate curved pieces of the human spine corresponded to his aesthetic taste 4. Human presence that could arouse the Erich Mendelsohn, empathy of viewers. Einstein -

Style Debates in Early 20Th-Century German Architectural Discourse

$UFKLWHFWXUDO Barnstone, DA. 2018. Style Debates in Early 20th-Century German Architectural Discourse. Architectural Histories, +LVWRULHV 6(1): 17, pp. 1–9. DOI: https://doi.org/10.5334/ah.300 RESEARCH ARTICLE Style Debates in Early 20th-Century German Architectural Discourse Deborah Ascher Barnstone In spite of the negative connotations ‘style’ has in contemporary architectural discourse, in early 20th- century Germany there was no consensus on the meaning or value of the concept amongst architects and critics. Although style was a dirty word for some like Hermann Muthesius, it represented the pinnacle of achievement for others like Walter Curt Behrendt. Against the backdrop of Behrendt’s famous Victory of the New Building Style, of 1927, were very diverse understandings of the term. This plurality was partly due to conceptual confusion between ‘the styles’ and ‘style’, but it was also a legacy of Gottfried Semper’s and Alois Riegl’s respective efforts to resituate style as a practical and historiographical tool. Although style was endlessly debated between 1910 and 1930 by German architects, critics, and intel- lectuals of all stripes, later scholars have either largely overlooked its significance or used the term as a way of describing a particular group of works with a narrow set of formal tropes. The debates, the conceptual confusion, and the incredible variety of opinion over style in early 20th-century discourse have not been addressed, especially in relation to practicing architects. This essay examines some of the intersecting positions of several important German practitioners to show how the notion of style served as a conceptual framework for divergent modern practices. -

Press Portfolio B a U H a U S C E N T E N a R Y 2 0 1 9 Programme Of

Press portfolio The Bauhaus Dessau in the Centenary Year 2019. B a u h a u s In 2019 the Bauhaus Association will celebrate the centenary of the founding C e n t e n a r y 2 0 1 9 of the Bauhaus as a cultural event across the whole of Germany. Its mem- bers are jointly organising an internationally-orientated cultural thematic year Programme of the Bauhaus Des- on the Bauhaus and modernism, which will also serve to boost Germany’s sau Foundation for the centenary tourism-related development as a home of modernism. of the founding of the Bauhaus. The Bauhaus Dessau Foundation's programme is based on many years of artistic and scientific research by the foundation, which is embedded in inter- P r e s s c o n t a c t national networks of universities and collection and research institutions. The highlight will be the opening of the Bauhaus Museum Dessau on 8 Septem- Ute König ber 2019. Another milestone will be the new performance of the Bauhaus +49-340-6508-238 buildings. And the Bauhaus Dessau Festivals with the festivals School FUN- [email protected] DAMENTAL, Architecture RADICAL and Stage TOTAL will also set a clear accent in the anniversary year. Bauhaus Dessau Foundation Gropiusallee 38 Press portfolio contents 06846 Dessau-Roßlau bauhaus-dessau.de The Centenary of the Founding of the Bauhaus. facebook.com/bauhausdessau The Bauhaus Association and the structure of the centenary. twitter.com/gropiusallee The Bauhaus Dessau Foundation. A brief description of the Foundation and its work. -

Carol's Faves

Carol’s Faves Architecture 1 Frank Lloyd Wright (1867-1959) Frank Lloyd Wright was an American architect, designer, writer, and educator. He designed more than 1,000 structures over a creative period of 70 years. Wright believed in designing in harmony with humanity and the environment, a philosophy he called organic architecture. This philosophy was exemplified in Fallingwater (1935), which has been called "the best all-time work of American architecture."[1] Wright played a key role in the architectural movements of the twentieth century, influencing generations of architects worldwide through his works.[2] Wright was the pioneer of what came to be called the Prairie School movement of architecture, and he also developed the concept of the Usonian home in Broadacre City, his unique vision for urban planning in the United States. In addition to his houses, Wright designed original and innovative offices, churches, schools, skyscrapers, hotels, museums, and other structures. He often designed interior elements for these buildings, as well, including furniture and stained glass. Wright wrote several books and numerous articles and was a popular lecturer in the United States and in Europe. He was recognized in 1991 by the American Institute of Architects as "the greatest American architect of all time."[1] In 2019, a selection of his work became a listed World Heritage Site as The 20th-Century Architecture of Frank Lloyd Wright. • https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=upNT0OFyErM • https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=muoVqVZ7RlM • https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Up5liqCUArI Johnson Wax Building • https://www.archdaily.com/881479/understanding-the-origins-of- the-open-plan-office-space Guggenheim • https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=S9XJT7bQrvg Bauhaus The Staatliches Bauhaus (German: "building house"), was a German art school operational from 1919 to 1933 that combined crafts and the fine arts.