An Annotated Bibliography on ESL and Bilingual Education in Guam and Other Areas of Micronesia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

OVERDUE FINES: 25¢ Por Day Per Item RETURNING LIBRARY MATERIALS: P'iace in Book Return to Remove Chars

OVERDUE FINES: 25¢ por day per Item RETURNING LIBRARY MATERIALS: P'Iace in book return to remove chars. from circuhtion recon © Copyright by JACQUELINE KORONA TEARE 1980 THE PACIFIC DAILY NEWS: THE SMALL TOWN NEWSPAPER COVERING A VAST FRONTIER By Jacqueline Korona Teare A THESIS Submitted to Michigan State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS School of Journalism 1980 ABSTRACT THE PACIFIC DAILY NEWS: THE SMALL TOWN NEWSPAPER COVERING A VAST FRONTIER 3y Jacqueline Korona Teare Three thousand miles west of Hawaii, the tips of volcanic mountains poke through the ocean surface to form the le-square- mile island of Guam. Residents of this island and surrounding island groups are isolated from the rest of the world by distance, time and, for some, by relatively primitive means of communication. Until recently, the only non-military, English-language daily news- paper serving this three million-square-mile section of the world was the Pacific Daily News, one of the 82 publications of the Rochester, New York-based Gannett Co., Inc. This study will trace the history of journalism on Guam, particularly the Pacific Daily News. It will show that the Navy established the daily Navy News during reconstruction efforts follow- ing World War II. That newspaper was sold in l950 to Guamanian civilian Joseph Flores, who sold the newspaper in 1969 to Hawaiian entrepreneur Chinn Ho and his partner. The following year, they sold the newspaper now called the Pacific Daily News, along with their other holdings, to Gannett. Jacqueline Korona Teare This study will also examine the role of the Pacific Daily Ngw§_in its unique community and attempt to assess how the newspaper might better serve its multi-lingual and multi-cultural readership in Guam and throughout Micronesia. -

CHAMORRO CULTURAL and RESEARCH CENTER Barbara Jean Cushing

CHAMORRO CULTURAL AND RESEARCH CENTER Barbara Jean Cushing December 2009 Submitted towards the fulfillment of the requirements for the Doctor of Architecture degree. University of Hawaii̒ at Mānoa School of Architecture Spencer Leineweber, Chairperson Joe Quinata Sharon Williams Barbara Jean Cushing 2 Chamorro Cultural and Research Center Chamorro Cultural and Research Center Barbara Jean Cushing December 2009 ___________________________________________________________ We certify that we have read this Doctorate Project and that, in our opinion, it is satisfactory in scope and quality in partial fulfillment for the degree of Doctor of Architecture in the School of Architecture, University of Hawaii̒ at Mānoa. Doctorate Project Committee ______________________________________________ Spencer Leineweber, Chairperson ______________________________________________ Joe Quinata ______________________________________________ Sharon Williams Barbara Jean Cushing 3 Chamorro Cultural and Research Center CONTENTS 04 Abstract phase 02 THE DESIGN 08 Field Of Study 93 The Next Step 11 Statement 96 Site Analysis 107 Program phase 01 THE RESEARCH 119 Three Concepts 14 Pre‐Contact 146 The Center 39 Post‐Contract 182 Conclusion 57 Case Studies 183 Works Sited 87 ARCH 548 186 Bibliography Barbara Jean Cushing 4 Chamorro Cultural and Research Center ABSTRACT PURPOSE My architectural doctorate thesis, titled ‘Chamorro Cultural and Research Center’, is the final educational work that displays the wealth of knowledge that I have obtained throughout the last nine years of my life. In this single document, it represents who I have become and identifies the path that I will be traveling in the years to follow. One thing was for certain when beginning this process, in that Guam and my Chamorro heritage were to be important components of the thesis. -

May 2016, Volume 5, Issue No

SharingHåfa the Håfa AdaiAdai Spirit with EverydayOur Visitors and Each Other May 2016, Volume 5, Issue No. 3 HÅFA ADAI PLEDGE CEREMONY LIVING THE HÅFA ADAI PLEDGE Creative indeed Fresh New Local Restaurant Three Squares Guam joins the Håfa Adai Pledge familia Håfa Adai Pledge signing ceremony held at Three Squares Restaurant Guam in Tamuning on Wednesday, April 20. Standing L-R: Rose Q. Cunlie, Guam Visitors Bureau, Director of Finance and Administration; Telo T. Taitague, Guam Visitors Bureau, Vice President; Marie Nededog Guerrero, Three Squares by B&G Pacific, LLC, Owner and CEO; Frank Guerrero, Three Squares by B&G Pacific, LLC, Representative; Nate Denight, Guam Visitors Bureau, President and Chief Executive Ocer and Pilar Laguana, Guam Visitors Bureau, Director of Global Marketing. Michelle Pier, owner and CEO of Creative Indeed. An independent artist and entrepreneur born on the island of Guam, Michelle Pier is known for her mesmerizing original acrylic paintings that incorporates GUAMPEDIA: Johnny Sablan the beauty of Guam. Pier has exhibited and sold hundreds of paintings locally and internationally. She is also known for establishing many of the local craft Keeping Chamorro culture through music fairs, festivals and other community events such as the Annual Luna Festival and Annual Holiday Craft Fair. It is through these events that inspires creativity among hundreds of local individuals, businesses and organizations. In Pier’s eorts, she has helped the local people to reconnect with their creativity and encourage them to create unique careers. It is also through these events that help connect local entrepreneurs and the community and to interact to promote “buy local”. -

Pacific Island History Poster Profiles

Pacific Island History Poster Profiles A Note for Teachers Acknowledgements Index of Profiles This Profiles are subject to copyright. Photocopying and general reproduction for teaching purposes is permitted. Reproduction of this material in part or whole for commercial purposes is forbidden unless written consent has been obtained from Queensland University of Technology. Requests can be made through the acknowldgements section of this pdf file. A Note for Teachers This series of National History Posters has been designed for individual and group Classroom use and Library display in secondary schools. The main aim is to promote in children an interest in their national history. By comparing their nation's history with what is presented on other Posters, students will appreciate the similarities and differences between their own history and that of their Pacific Island neighbours. The student activities are designed to stimulate comparison and further inquiry into aspects of their own and other's past. The National History Posters will serve a further purpose when used as a permanent display in a designated “History” classroom, public space or foyer in the school or for special Parent- Teacher nights, History Days and Education Days. The National History Posters do not offer a complete survey of each nation's history. They are only a profile. They are a short-cut to key people, key events and the broad sweep of history from original settlement to the present. There are many gaps. The posters therefore serve as a stimulus for students to add, delete, correct and argue about what should or should not be included in their Nation's History Profile. -

Elak Sra Onak Project

UNIVF:RSITY OF HAWAl'I LIBRARY ELAK SRA ONAK PROJECT Volume one, Issue two September 2004 ACKNOWLEDGMENT TIW proj«t u funded i11 whole or in part by tlte US National Park Savka and tM Kosru State Govan1M11t, DepartJMnt of Agriculture Land & Fisheries ,. INTRODUCTION The Elak Sra Onak Project is happy to present to you the Volume one, Issue two Elak Sra Onak Book. This issue is a continuation ofvolume one. This issue is specifically discusses four of Kosrae's areas of Culture. These four areas are: Ideology which presents mostly on the Religious activities, Beliefs, Changes is religion such as new churches and conversions, other aspects of ideology such as stories about people and events in different times, and ideas about the proper way people should act toward one another. Another area is the Cultural Transmission which discusses how culture is passed on to new generations, formal and informal education ofways ofmaking a living, values, and social structure, how are schools organized in Kosrae, who are the teachers, how are they trained, where does the curriculum come from, how do school activities relate to informal education in homes and other places, what are Kosrae's games and how do they reflect Kosrae culture. The last section talks about Social Structure and Changes which will present to you, how has Kosrae changed, what are some of the things that are causing the changes today such as the video cassette recorders(VCRs), the ctrcumfrenttal road or the new airport, who are the people who introduce changes, how is change accepted by different people in each village, how does each village react to change, the role of institutions and their acceptance or resistance to change. -

An Exploratory Study of Community Trauma and Culturally Responsive Counseling with Chamorro Clients. Patricia Taimanglo Pier University of Massachusetts Amherst

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014 1-1-1998 An exploratory study of community trauma and culturally responsive counseling with Chamorro clients. Patricia Taimanglo Pier University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_1 Recommended Citation Pier, Patricia Taimanglo, "An exploratory study of community trauma and culturally responsive counseling with Chamorro clients." (1998). Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014. 1257. https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_1/1257 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014 by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. AN EXPLORATORY STUDY OF COMMUNITY TRAUMA AND CULTURALLY RESPONSIVE COUNSELING WITH CHAMORRO CLIENTS A Dissertation Presented by PATRICIA TAIMANGLO PIER Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts Amherst in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May 1998 School and Counseling Psychology Patricia Taimanglo Pier 1998 (5) Copyright by All Rights Reserved AN EXPLORATORY STUDY OF COMMUNITY TRAUMA AND CULTURALLY RESPONSIVE COUNSELING WITH CHAMORRO CLIENTS A Dissertation Presented by PATRICIA TAIMANGLO PIER Approved as to style and content by: Allen E. Ivey, Chairperson of Committee ACKINOWLEDGIMKN I S My journey through this paper was made possible by the countless gifts of support, time, and energy from my family, professors, participants, and friends l)r Allen F Ivey, my deepest gratitude for your unconditional faith in my work Dr Janine Robert, I am indebted to you for your enriching energy, keen eye for detail and supportive voice throughout the process Dr. -

Living the Guam Brand Day 1

Guam Visitors Bureau Conference Naʼlåʼlaʼ i Kostumbren Guåhan Ta Naʼfandanñaʼ i Bisitå-ta yan i Kotturå-ta Living the Guam Brand Bringing together our culture and our visitors April 7 - 8, 2011 Hyatt Regency, Tumon Guam Setbison Bisitan Guåhan, CHaCO Guam Visitors Bureau, CHaCO and funding for this e-publication provided by Inangokkon Inadahi Guahan Guam Preservation Trust Table of Contents Na"lå"la" i Kostumbren Guåhan | Living the Guam Brand Ta Na"fandanña" i Bisitå-ta yan i Kotturå-ta | Bringing together our culture and our visitors Day One – Diha 7 gi Abrit 2011 | April 7, 2011 ! 1! Mensåhen Finatto! Unuråpble Eddie Baza Calvo, Governor of Guam !! Welcome Remarks! Honorable Eddie Baza Calvo, Maga"låhen Guåhan ! 5! Hestoria Put i Kostumbre! Gerald S. A. Perez, Consultant, GVB !! History of the Brand! Konsuttånte, Setbision Bisitan Guåhan ! 15! Inadilånton Kostumbre|Binisita ! Rhonda Brauer, Director, !! Put Kotturagi Pumalu na Lugåt siha! Burson Marstellar !! Developing the Brand/Cultural! Direktoran Minaneha, Burson Marstellar !! Tourism in other Destinations ! 21! I pao Guåhan! Sinadora Tina Muña Barnes !! The Guam Essence! Mina"trentai unu na Liheslaturan Guåhan !! Guaha Kottura?! Senator, 31st Guam Legislature !! Got Culture! ! 25! Inembråsian Kostumbren Guåhan-! Judy Flores, Ph.D., !! Hinasso yan Siñenten Kottura! Bisa-Ge"helo", Irensian Kottura yan !! Embracing the Guam Brand! Hiniyong Kumunidåt; Membro, Inetnon !! -Cultural Perspectives! Direktot, Setbision Bisitan Guåhan !! ! ! Vice-Chairperson, Cultural Heritage and !!!! Community Outreach; GVB Board Member ! 31! Inembråsian Kostumbren Guåhan:! Mary Torre, President, !! Hinasso yan Siñenten Endostriha! Guam Hotel and Restaurant Association !! Embracing the Guam Brand:! !! Industry Perspectives ! 43! Sesion Dinestilådu !! Breakout Sessions !! ! 47! 1. Hestoria yan Irensia! Anne P. -

EVIDENCE for the ORIGINS of the CHAMORRO PEOPLE of the MARIANA ISLANDS a Paper Presented to Dr. Douglas Oliver Dr. Donald Toppin

..;:, EVIDENCE FOR THE ORIGINS OF THE CHAMORRO PEOPLE OF THE MARIANA ISLANDS A Paper Presented to Dr. Douglas Oliver Dr. Donald Topping Dr. Timothy Macnaught In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree M.A. in Pacific Island Studies by Robert Graham University of Hawaii November, 1977 '1'l1e Pacific Islands Program, Plan B, requires: "The student's demonstration of research capacity by the submission a major paper prepared for a 600 or 700 numbered research course." (1977-1979 Graduate Information Bulletin, University of Hawaii, ~anoa, p.B7) The submission of this paper to Drs. Oliver, Topping and Macnaught represents the fulfillemnt of that requirement. The paper was researched and written in the Gprin~ semester of 1977 for a course in the ESL department (ESL 660, Sociolinguistics). Since that time I have submitted this manuscript to a number of people to read and comment on. In rewriting this paper in Oct:>ber, 1977, I have made use of their comments and suggestions. Those who have commented on the paper include Dr. Richard Schmidt, to whom the paper was originally submitted, Dr. Donald Topping (SSLI and authority on Chamorro language), Dan Koch (Chamorro languaGe teacher) and Lolita Huxel (Chamorro language teacher). To them go my thanks for advice. Of course all responsibility remains my own. Robert Graham October, 1977 TABLE OF CONTENTS Table of Contents •...•...•. · . .. • 1 The Setting .......•..... ...• ii Map of Oceania ..••. .. · .... ·. iii Map of Marianas ..•...••... · . .. i v Chapter I The Evidence Through Language Splitting ...• 1 Dyen's Work.. .•.•......• . 4 Conclusions .. •• ••••.•••• • 7 Chapter II Ethnographic Evidence for Early Origins • • 7 Conclusions . -

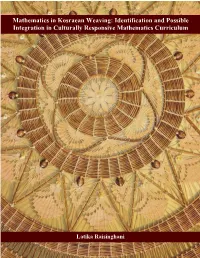

Mathematics in Kosraean Weaving Mathematics in Kosraean Weaving: Identification and Possible

Mathematics in Kosraean Weaving Mathematics in Kosraean Weaving: Identification and Possible Integration in Culturally Responsive Mathematics Curriculum Latika Raisinghani 1 Mathematics in Kosraean Weaving Mathematics in Kosraean Weaving: Identification and Possible Integration in Culturally Responsive Mathematics Curriculum Latika Raisinghani Assistant Professor Education and Science Department College of Micronesia-FSM Kosrae FM 96944 Micronesia E-mail: [email protected] 2 Mathematics in Kosraean Weaving Introduction This paper focuses on identification and description of mathematical ideas, patterns and thinking involved in the making of specific artifacts of weaving (otwot) in Kosrae, using coconut leaves and fibers (sroacnu), pandanus leaves (lol) and hibiscus bast (ne), and their possible integration in a culturally responsive Mathematics curriculum. Kosrae (pronounced as Ko-shry), also called the “Island of the Sleeping Lady”, is the only island state within the Federated States of Micronesia (FSM) that does not have any outer islands. It is of volcanic origin and is believed to have been formed by the shifting of the great Pacific Tectonic Plate, which was later called the Caroline Plate, approximately 3,000,000 years ago. Kosrae had many other names as well: Kusaie, Katau, Kato, Kosiu, Kusae, Carao Tevya, Strong’s Island, Hope Island; however, the people who found it used none of these. They called it Kosrae (Segal, 1995). Dr. Ernst Sarfert described Kosrae as “the most beautiful island of the great ocean, as honoring its name ‘Gem of the Pacific’ indicates, which it received at the time of its highest popularity with the white people” (Sarfert, 1919). Kosrae covers an area of 42.31 square miles and is roughly triangular in shape. -

Pacific Youth: Local and Global Futures

PACIFIC YOUTH LOCAL AND GLOBAL FUTURES PACIFIC YOUTH LOCAL AND GLOBAL FUTURES EDITED BY HELEN LEE PACIFIC SERIES Published by ANU Press The Australian National University Acton ACT 2601, Australia Email: [email protected] Available to download for free at press.anu.edu.au ISBN (print): 9781760463212 ISBN (online): 9781760463229 WorldCat (print): 1125205462 WorldCat (online): 1125270333 DOI: 10.22459/PY.2019 This title is published under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial- NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0). The full licence terms are available at creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/legalcode Cover design and layout by ANU Press Cover photograph: ‘Two local youths explore their backyard beach in Tupapa, Rarotonga’ by Ioana Turia This edition © 2019 ANU Press Contents 1. Pacific Youth, Local and Global ..........................1 Helen Lee and Aidan Craney 2. Flexibility, Possibility and the Paradoxes of the Present: Tongan Youth Moving into the Future .....................33 Mary K Good 3. Economic Changes and the Unequal Lives of Young People among the Wampar in Papua New Guinea. 57 Doris Bacalzo 4. ‘Things Still Fall Apart’: A Political Economy Analysis of State—Youth Engagement in Honiara, Solomon Islands .......79 Daniel Evans 5. The New Nobility: Tonga’s Young Traditional Leaders ........111 Helen Lee 6. Youth Leadership in Fiji and Solomon Islands: Creating Opportunities for Civic Engagement. 137 Aidan Craney 7. Entrepreneurship and Social Action Among Youth in American Sāmoa .................................159 Aaron John Robarts Ferguson 8. Youth’s Displaced Aggression in Rural Papua New Guinea ....183 Imelda Ambelye 9. From Drunken Demeanour to Doping: Shifting Parameters of Maturation among Marshall Islanders ..................203 Laurence Marshall Carucci 10. -

A Case Study from Micronesia the Following: David A

In this issue – Grass Roots Language Preservation – Bilingual Living in a ‘Monolingual’ Country – Multicultural Adoption News and Views for Intercultural People – Too Much of a Good Thing? Editors: Sami Grover & Marjukka Grover 2003, Vol 20 No.3 – News from the USA EDITORIAL PRESERVING LANGUAGE FROM THE BOTTOM UP: All too often bi/multilinguals are asked A Case Study From Micronesia the following: David A. Hough and Alister Tolenoa ‘What exactly is the point of preserving your Spanish/ German/ Arabic/ Urdu ?’ Pohnpeian, with Kiribati, Nauruan and (delete as appropriate) Chuukese also related. In a world where English predominates, Much of Kosrae’s early history has been monolinguals can find it hard to lost because of colonisation and understand that language can mean so depopulation. From 1840–1880 the much more than just being a tool for population decreased from about 7000 to communication. For many of us, our 300 due to diseases brought by Western multiple languages are important links to whaling ships. Direct colonial rule our heritage and our cultural identities. followed, first under Spain until 1898, They are part of who we are. then Germany until 1914, Japan from 1914 until 1945, and following that the In this issue we hear from David Hough Official efforts to preserve a language, and Alister Tolenoa on a language United States. The legacy of this or anything else for that matter, are colonialism is still very much alive. program in Micronesia that is often led from the top down by empowering the inhabitants of a tiny government and experts who may not Today, the island is part of the Federated island to preserve their own language. -

Tungusic Languages

641 TUNGUSIC LANGUAGES he last Imperial family that reigned in Beij- Nanai or Goldi has about 7,000 speakers on the T ing, the Qing or Manchu dynasty, seized banks ofthe lower Amur. power in 1644 and were driven out in 1912. Orochen has about 2,000 speakers in northern Manchu was the ancestral language ofthe Qing Manchuria. court and was once a major language ofthe Several other Tungusic languages survive, north-eastern province ofManchuria, bridge- with only a few hundred speakers apiece. head ofthe Japanese invasion ofChina in the 1930s. It belongs to the little-known Tungusic group Numerals in Manchu, Evenki and Nanai oflanguages, usually believed to formpart ofthe Manchu Evenki Nanai ALTAIC family. All Tungusic languages are spo- 1 emu umuÅn emun ken by very small population groups in northern 2 juwe dyuÅr dyuer China and eastern Siberia. 3 ilan ilan ilan Manchu is the only Tungusic language with a 4 duin digin duin written history. In the 17th century the Manchu 5 sunja tungga toinga rulers ofChina, who had at firstruled through 6 ninggun nyungun nyungun the medium of MONGOLIAN, adapted Mongolian 7 nadan nadan nadan script to their own language, drawing some ideas 8 jakon dyapkun dyakpun from the Korean syllabary. However, in the 18th 9 uyun eÅgin khuyun and 19th centuries Chinese ± language ofan 10 juwan dyaÅn dyoan overwhelming majority ± gradually replaced Manchu in all official and literary contexts. From George L. Campbell, Compendium of the world's languages (London: Routledge, 1991) The Tungusic languages Even or Lamut has 7,000 speakers in Sakha, the Kamchatka peninsula and the eastern Siberian The mountain forest coast ofRussia.