EU After Covid Materials

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

EDUCATION UCLA Graduate School of Architecture & Urban Design

Ryan Brooke Thomas Abbreviated CV 2021 Kalos Eidos +1.646.416.1407 kaloseidos.com [email protected] EDUCATION UCLA Graduate School Of Architecture & Urban Design, Los Angeles, CA | 1999-2002 Degree: Master of Architecture I Awards/Honors: Best Design Studio Project, Thesis Studio | 2001-2002; Selected Exhibitor U.S. Pavilion, Venice Architecture Biennale | 2000; Graduate Fellowship in Architecture | 1999-2000 Columbia University GSAPP, New York, NY | 1998 Program: Introduction to Architecture Stanford University, Palo Alto, CA | 1994-1998 Degree: Bachelor of Arts, with Honors, Major: Modern Thought & Literature, Humanities Honors Program Other: NCAA Division I Student-Athlete in Cross Country and Track & Field ACADEMIC EXPERIENCE The Cooper Union, The Irwin S. Chanin School of Architecture, Assistant Professor Adjunct | New York, NY | 2021-Present Courses: Design II Syracuse University School of Architecture, Part-time Studio Instructor | Syracuse, NY | 2020-2021 Courses: Architectural Design IV, Architectural Design V Pratt Institute Graduate Architecture & Urban Design, Visiting Assistant Professor | New York, NY | 2018-2019 Courses: Design I Parsons School of Design, Constructed Environments, Visiting Instructor | New York, NY | 2016-2018 Courses: Interior Design 5, Interior Design 4 Syracuse University School of Architecture, Assistant Professor Adjunct | Syracuse, NY | 2009-2011 Courses: Architectural Design V, Architectural Design VI, Architectural Design I Graduate & Undergraduate Architecture and Design Programs, Visiting Design -

Nyc Youth Innovators Showcase Technology Projects Designed to Make Positive Change at Emoti-Con 2017

NYC YOUTH INNOVATORS SHOWCASE TECHNOLOGY PROJECTS DESIGNED TO MAKE POSITIVE CHANGE AT EMOTI-CON 2017 Ninth Annual Emoti-Con Digital Media and Technology Challenge Unites New York City Youth Around Technology and Social Change th NEW YORK CITY, June 5, 2017— On Saturday, June 17 , youth from across New York City will connect, compete, and present their technology projects at Emoti-Con, held in the Celeste Bartos Forum in The New York Public Library. In its ninth year, Emoti-Con is New York City’s biggest showcase for young designers, makers, technologists, and tinkerers who believe in digital innovation as a tool for positive change in the world around them. Through this annual event, Emoti-Con brings together diverse middle and high school students to collaborate with their peers, connect with those with whom they share a common identity as youth media producers and technologists, and receive recognition for the incredible work they do throughout the year. Emoti-Con ensures that young people in NYC can offer their voice about pressing issues, gain vital exposure to industry mentors, and most importantly, be part of a community that will be instrumental in helping solve the challenges of their time. Emoti-Con is the largest event of its kind among informal learning programs in NYC and has been developed through a unique collaboration between NYC youth-serving organizations and Hive NYC Learning Network members. This year’s organizers include Mouse, Mozilla, Hive Research Lab, The New York Public Library and Parsons School of Design at The New School. The event will include keynote presentations, hands-on activities, and a Youth Media Expo, showcasing youth projects from several organizations, such as All Star Code, Girls Who Code, Global Kids, Girl Scouts of Greater New York, Mouse, Nano Hacker Academy, NYC Parks/EVC, STEM from Dance, and ScriptEd. -

New School Histories

New School Histories ULEC2800, Fall 2019 Tuesday, 4:00-5:15pm Julia Foulkes, [email protected], 66 W. 12th St., Rm 908 Rm. 104, Univ. Center Mark Larrimore, [email protected], 65 W.11th St., Rm 454 When the New School for Social Research opened its doors a hundred years ago, it offered courses in the social sciences and public affairs – and a new vision of higher education. It was not a university; it did not offer degrees. The founders thought that people would come to the school for “no other purpose than to learn.” A century later, the New School has changed in almost every way. Design, the arts, a spirit of activism, and degree programs dominate. But the school continues to strive to offer disciplinary experimentation, political involvement, and a global lens that offers a critical perspective on higher education. In what ways have these values been realized (or not), and how? We construct answers to these questions by assembling a history of the school from scrapbooks of newspaper articles, memoirs, artwork, and interviews. The basis of the course are the academic and artistic works of The New School’s faculty and students since its establishment. We will also participate in university centenary activities throughout the semester. Learning Objectives ● Learn about archives, how to navigate them and build historical interpretations from sources in them. ● Learn various research methods, including archival investigation and interviews. ● Understand central issues of higher education over the last century and into the future. ● Write papers that convey analytical thinking, a command of readings, original ideas, and accurate acknowledgement of sources. -

ECHO,Conference,-,Speaker,Profiles

Dr Alberto Alemanno is Jean Monnet Professor of Law at Ecole des Hautes Etudes Commerciales (HEC) Paris and Global Clinical Professor at New York University School of Law. Alberto’s research has been centered on the role of - and need for – evidence and public input in domestic and supranational policymaking. In particular, he has been focusing on and promoting the study of the emerging law and policy of risk regulation in both the EU and the WTO legal orders. He has explored, in particular, the use of scientific evidence and behavioural research - as drawn from psychology, cognitive sciences and economics - in regulatory decision-making and in the judicial review of science-based measures by courts. At present, he is working on the legal implications and potential contribution of behavioural research in policymaking across policy areas. Due to his commitment to bridge the gap between academic research and policy action, he regularly provides advice to a variety of NGOs and governments across the world as well as international organizations, such as the the European Commission, the European Parliament, the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development, the World Health Organisation, on various aspects of European Union law, international regulatory cooperation, international trade and global health law as well as evidence-based policymaking. Originally from Italy, Alemanno is a graduate of the College of Europe and Harvard Law School. He holds a PhD in International Law and Economics from Bocconi University. Prior to entering academia full-time, he clerked at the Court of Justice of the European Union, worked as a Teaching Assistant at the College of Europe in Bruges and qualified as an attorney at law in New York. -

Zewei Hong | Graduates | CFDA

FASHION FUTURE GRADUATE SHOWCASE BROWSE FUTURE GRADUATES A B C G H I J K L M N P Q R S T V W Y Z ABOUT THE PROGRAM The CFDA x NYCEDC 2018 Fashion Future Graduate Showcase is a hybrid physical and digital showcase for top talent seeking employment and visibility in New York. As an extension of the New York City Economic Development Corporation’s Made in NY Initiative and CFDA Education + Professional Development, the multi-experience platform will connect exemplary New York and select invited fashion graduates across all design specializations including Apparel, Accessories, Jewelry, Textiles/Materials, Technical Design, and relevant emerging fashion pathways such as sustainable systems to professional opportunity. 2018 Fashion Future Graduate Showcase will take place be at Industria Studios from July 9-10. The showcase is integrated into New York Fashion Week: Men’s. Fifty-three graduates from eight leading design colleges and universities will participate this year. The invited colleges are Fashion Institute of Technology, Parsons School of Design, Pratt Institute, Academy of Art University, California College of the Arts, Kent State University, Rhode Island School of Design, and Savannah College of Art and Design. For more information, please email Stephanie Soto, [email protected] ! 01 / 50 " Zhouyi Li, Academy of Art University PARTICIPATING SCHOOLS PARSONS SCHOOL OF DESIGN The New School's Parsons School of Design, founded in 1896, is a leading institution for art and design education in the world. Based in New York, the school offers undergraduate and graduate programs in the full spectrum of art and design disciplines, as well as online courses, degree and certificate programs. -

Architecture Program Report for 2016 NAAB Visit for Continuing Accreditation

Parsons School of Design School of Constructed Environments Architecture Program Report for 2016 NAAB Visit for Continuing Accreditation Master of Architecture [preprofessional degree + 90 Credits] Master of Architecture + Advanced Standing [preprofessional degree + 60 Credits] Year of the Previous Visit: 2010 Current Term of Accreditation: “Master of Architecture was formally granted a sixyear term of accreditation. The accreditation term is effective January 1, 2010. The program is scheduled for its next accreditation visit in 2016” (source: NAAB letter to J. Robert Kerrey, President, Parsons the New School for Design, dated July 27th, 2010) Submitted to: The National Architectural Accrediting Board Date: September 7th, 2015 Parsons School of Design School of Constructed Environments Architecture Program Report September 2015 Program Administrator: Professor Andrew Bernheimer, AIA NCARB, Director 25 East 13th Street New York NY 10003 T. 2122298955 ext 3888 email: [email protected] Chief Academic Officer of the academic unit: Joel Towers, Executive Dean, Parsons School of Design 66 5th Avenue New York NY 10011 2122298950 x4393 email: [email protected] Chief administrator for the academic unit in which the program is located : Brian McGrath, Dean, School of Constructed Environments 25 East 13th Street New York NY 10003 T. 2122298955 email: [email protected] Chief Academic Officer of the Institution: Tim Marshall, Provost and Chief Academic Officer, The New School 66 West 12th Street New York NY 10011 T. 212.229.8947 -

ZINGUER CV October 2015

TAMAR ZINGUER Ph.D., MA, M.Sc., B.Arch c u r r i c u l u m v i t a e ______________________________________________________________________________ The Cooper Union phone: (609) 933-9933 41 Cooper Square [email protected] New York, NY 10003 [email protected] EDUCATION 2006 Ph.D. - Princeton University, School of Architecture, Princeton NJ Doctor of Philosophy in History and Theory of Architecture “Architecture in Play: Intimations of Modernism in Architectural Toys 1836-1952” Ph.D. Advisors: Beatriz Colomina, Hal Foster Ph.D. Committee: Anthony Vidler, Antoine Picon, Spyros Papapetros 2001 MA - Princeton University, School of Architecture, Princeton NJ 1998 M.Sc. - Technion Israel Institute of Technology Faculty of Architecture and Town Planning, Haifa Israel Masters of Science in Architecture, “Minimalism in Architecture” Advisor: Robert Oxman, Committee: Yaakov Rechter 1989 B.Arch. The Cooper Union, Irwin S. Chanin School of Architecture, NYC Thesis advisor: John Hejduk TEACHING EXPERIENCE Spring 2016 Visiting Associate Professor – Princeton University, Princeton, NJ The History of Architectural Theory (ARC 308) 2005-present Associate Professor – The Cooper Union, The Irwin S. Chanin School of Architecture, New York, NY Coordinator of Third Year Design Studio, 2006-2009, 2015-16 Proseminars for M.Arch II: “Invention in American Architecture”, 2012, 2014 “Writing Architecture” 2013, 2105 History of Modern Architecture 1750-1950 (Survey) 2010-Present Advanced Topics Seminars: “Architecture in Play” 2009- 2013 Coordinator of First -

Thomas Werner Projects

Thomas Werner 917.498.3069 [email protected] EDUCATION Masters of Fine Art New Media Arts and Performance, Long Island University Bachelor of Arts Photography, with an emphasis in film, The Art Center College of Design in Pasadena, California Bachelor of Science Communications, with an emphasis in film, University of Wisconsin at Madison Research assistant, Ed Donnerstein, The effects of sex and violence in film Continuing Education Web Teaching Tools 2.0, Graduate course, Parsons School of Design, New York, New York ACADEMIC APPOINTMENTS 2019 - 2020 Adjunct Faculty, New York Film Academy, New York 07/2010–07/2019 Assistant Professor of Photography, Parsons School of Design, School of Art, Media and Technology, New York, New York 2003-05 Adjunct Faculty, Parsons School of Design, Photography Program ACADEMIC LEADERSHIP 7/1/06 - 6/30/10 Director of the BFA of Photography, Assistant Professor of Photography Parsons School of Design, New York, New York Oversaw the development and coordination of the Program and its curriculum. In addition to managing students, faculty, union, and other internal and external aspects of the Program. 7/1/05 - 6/30/06 Interim Director of the BFA of Photography, Visiting Assistant Professor Parsons School of Design, New York, New York PROFESSIONAL EXPERIENCE 2017 – Present Thomas Werner Projects 2016 - Present Editor at Large, IRKmagazine Editor at Large for IRKmagazine, a Paris based fashion and culture web site and print publication distributed internationally in boutique shops, trend stores and -

2021 College Acceptances

Recent College and University Acceptances Recent Bosco Tech graduates have earned spots at prestigious colleges and universities across the country, including: Academy of the Arts University California State University, Bakersfield College of William & Mary Adams State University California State University, Colorado State University Channel Islands Adrian College Columbia University California State University, Chico Amherst College Concordia University California State University, Arizona State University Dominguez Hills Cornell College Art Center College of Design California State University, East Bay Cornell University Assumption College California State University, Fresno Creighton University Azusa Pacific University California State University, Fullerton Culver-Stockton College Biola University California State University, Long Beach DePaul University Boise State University California State University, Los Angeles Dominican University Boston College California State University, Monterey Bay Drexel University Boston University California State University, Northridge Earlham College Brandeis University California State University, Sacramento Eastern Kentucky University Brown University California State University, San Bernardino Embry-Riddle Aeronautical University Buena Vista University California State University, San Marcos Emerson College California Baptist University Carnegie-Mellon University Fairleigh Dickinson University California Institute of Technology Cazenovia College Florida Institute of Technology California Lutheran -

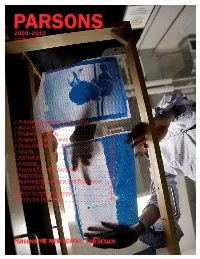

Parsons 2009–2010 Catalog

PARSONS 2009–2010 CATALOG > Academic Calendar 2009–2010 2 > About Parsons 3 > Programs of Study 4 > Program Requirements 6 > Study Options 20 > Faculty 22 > Admission 27 > Advising 31 > Student Financial Services 32 > Registration 35 > Academic Regulations and Procedures 36 > Student Life 44 > Other University Policies 47 > About the University 49 ACADEMIC CALENDAR 2009–2010 Fall 2009 Spring 2010 Registration March 30–May 1 (registration for Registration November 2–30 (registration for continuing students) continuing students) Registration for new students; Registration for new students; late reg. for continuing students) August 24–28 late reg. for continuing students January 19–22 Classes begin Monday, August 31 Classes begin Monday, January 25 Convocation Thursday, September 3 Last day to add a class Friday, February 5 Last day to add a class Monday, September 14 Last day to drop a class Friday, February 12 Last day to drop a class Monday, September 21 Last day to withdraw from a class with a grade of W Last day to withdraw from a class with a grade of W Undergraduate students Friday, March 12 Undergraduate students Monday, October 19 Parsons graduate students Friday, March 12 Parsons graduate students Monday, October 19 All other graduate students Monday, May 17 All other graduate students Friday, December 18 Holidays Martin Luther King Day: Monday, January 18 Holidays Labor Day Weekend: Saturday–Monday, September 5–7 President’s Day: Monday, February 15 Rosh Hashanah: Friday–Saturday, Spring break: Monday–Sunday, September 18 eve*–September 19 March 15–21 Yom Kippur: Sunday–Monday, September 27 eve*–September 28 Fall 2010 registration April 5–30 *No classes that begin Friday and Sunday Juries Arranged by program 4:00 p.m. -

Art College Readiness Resource ART COLLEGE READINESS RESOURCE

Art College Readiness Resource ART COLLEGE READINESS RESOURCE Contents Introduction 1 General College Admissions Timeline 2 How to Find Information on Colleges 4 Application and Decision Plans 6 Common Application 7 List of Available Art Programs and Internships 8 Immigrant Students (Documented and Undocumented) 10 Scholastic Assessment Test (SAT) Preparation Workshops 11 College Advisory Programs 12 Financial Aid 13 Free Application for Federal Student Aid (FASFA) 14 Financial Aid Programs 15 Types of Schools Available 17 Types of Art Schools 17 List of Art Schools and Colleges with Art Programs 19 College Majors and Careers in Art 28 Careers in the Arts 35 Bibliography 36 Content Contributors 37 3 ART COLLEGE READINESS RESOURCE Introduction This booklet was made to act as an all-encompassing guide to the art school application process Within, students will find information covering researching colleges, art majors, financial aid, and much more. The Joan Mitchell Foundation designed this book in mind to prepare more high school students for college, given that many here in New York lack info Too few students in this city are informed of the application process and many high schools don’t always have the resources available to teach them The information presented here is the product of extensive research from various sources (see bibliography) as well as from the staff of the Joan Mitchell Foundation. All was compiled and organized solely to act as a helpful reference for students interested in applying to art school 1 ART COLLEGE READINESS -

Cathedral High School Magazine | Spring/Summer 2020

THE CATHEDRAL CATHEDRAL HIGHConnection SCHOOL MAGAZINE | SPRING/SUMMER 2020 A MAGAZINE FOR ALUMNAE AND FRIENDS THE CATHEDRAL HIGH SCHOOL MAGAZINE | SPRING/SUMMER 2020 CLASS OF 2020 CONGRATULATIONS CLASS OF 2020 athedral High School has an outstanding track record in Cgraduating students and helping them get into college with academic scholarships and substantial financial aid. Nearly 100% of our graduating seniors attend college. For many families these students are the first to graduate high school and attend the college of their choice. Cathedral’s senior class of 98 students have been accepted to 125 schools, offering over $20 million in scholarships and awards! Check out the impressive colleges and universities: Adelphi University • Adelphi University Honors College • Albright College Technology • Ohio University • Otis College of Art and Design • Pace • Alfred University • Barry University • Berkeley College • Boston University • Pace University Pforzheimer Honors College • Penn State College • Bowie State University • Caldwell University • Cazenovia University • Penn State University Abington Honors Program • Pratt College • Clark Atlanta University Honors and Scholars Program • Institute • Pratt Munson-Williams-Proctor Arts Institute • Rensselaer Clark University • College of Mount St. Vincent • CUNY Baruch College Polytechnic University • Rutgers University • Sacred Heart University • • CUNY Borough of Manhattan Community College • CUNY Bronx Saint Peter’s University • Savannah College of Art and Design Scholars Community College • CUNY Brooklyn College • CUNY The City College Program • School of Art Institute of Chicago • School of Visual Arts • of New York • CUNY Hunter College • CUNY LaGuardia College • CUNY Scranton University • Seton Hall University • Siena College • Southern Lehman College • CUNY Medgar Evers College • CUNY NYC College of New Hampshire University • Spelman College • St.