The Technique of Revolution

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A British Reflection: the Relationship Between Dante's Comedy and The

A British Reflection: the Relationship between Dante’s Comedy and the Italian Fascist Movement and Regime during the 1920s and 1930s with references to the Risorgimento. Keon Esky A thesis submitted in fulfilment of requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences. University of Sydney 2016 KEON ESKY Fig. 1 Raffaello Sanzio, ‘La Disputa’ (detail) 1510-11, Fresco - Stanza della Segnatura, Palazzi Pontifici, Vatican. KEON ESKY ii I dedicate this thesis to my late father who would have wanted me to embark on such a journey, and to my partner who with patience and love has never stopped believing that I could do it. KEON ESKY iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This thesis owes a debt of gratitude to many people in many different countries, and indeed continents. They have all contributed in various measures to the completion of this endeavour. However, this study is deeply indebted first and foremost to my supervisor Dr. Francesco Borghesi. Without his assistance throughout these many years, this thesis would not have been possible. For his support, patience, motivation, and vast knowledge I shall be forever thankful. He truly was my Virgil. Besides my supervisor, I would like to thank the whole Department of Italian Studies at the University of Sydney, who have patiently worked with me and assisted me when I needed it. My sincere thanks go to Dr. Rubino and the rest of the committees that in the years have formed the panel for the Annual Reviews for their insightful comments and encouragement, but equally for their firm questioning, which helped me widening the scope of my research and accept other perspectives. -

Naples and the Nation in Cultural Representations of the Allied Occupation. California Italian Studies, 7(2)

Glynn, R. (2017). Naples and the Nation in Cultural Representations of the Allied Occupation. California Italian Studies, 7(2). https://escholarship.org/uc/item/1vp8t8dz Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record License (if available): CC BY-NC Link to publication record in Explore Bristol Research PDF-document This is the final published version of the article (version of record). It first appeared online via University of California at https://escholarship.org/uc/item/1vp8t8dz . Please refer to any applicable terms of use of the publisher. University of Bristol - Explore Bristol Research General rights This document is made available in accordance with publisher policies. Please cite only the published version using the reference above. Full terms of use are available: http://www.bristol.ac.uk/red/research-policy/pure/user-guides/ebr-terms/ UC Berkeley California Italian Studies Title Naples and the Nation in Cultural Representations of the Allied Occupation Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/1vp8t8dz Journal California Italian Studies, 7(2) Author Glynn, Ruth Publication Date 2017-01-01 License CC BY-NC 4.0 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Naples and the Nation in Cultural Representations of the Allied Occupation Ruth Glynn The Allied Occupation in 1943–45 represents a key moment in the history of Naples and its relationship with the outside world. The arrival of the American Fifth Army on October 1, 1943 represented the military liberation of the city from both Nazi fascism and starvation, and inaugurated an extraordinary socio-cultural encounter between the international troops of the Allied forces and a war-weary population. -

United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, 2000)

The Destruction and Rescue of Jewish Children in Bessarabia, Bukovina, and Transnistria (1941–1944)* Radu Ioanid Approximately one-half of Romania’s prewar Jewish population of 756,000 survived World War II. As a consequence of wartime border changes, 150,000 of the original Jewish population ended up under Hungarian sovereignty in northern Transylvania. In 1944 these Jews were deported to concentration camps and extermination centers in the Greater Reich and nearly all of them—130,000—perished before the end of the war. In Romania proper more than 45,000 Jews—probably closer to 60,000—were killed in Bessarabia and Bukovina by Romanian and German troops during summer and fall 1941. The remaining Jews from Bessarabia and almost all remaining Jews from Bukovina were then deported to Transnistria, where at least 75,000 died. During the postwar trial of Romanian war criminals, Wilhelm Filderman—president of the Federation of Romanian Jewish Communities—declared that at least 150,000 Bessarabian and Bukovinan Jews (those killed in these regions and those deported to Transnistria and killed there) died under the Antonescu regime. In Transnistria at least 130,000 indigenous Jews were liquidated, especially in Odessa and the districts of Golta and Berezovka. In all at least 250,000 Jews under Romanian jurisdiction died, either on the explicit orders of Romanian officials or as a result of their criminal barbarity.1 However, Romanian Zionist leader Misu Benvenisti estimated 270,000,2 the same figure calculated by Raul Hilberg.3 During the Holocaust in Romania, Jews were executed, deported, or killed by forced labor or typhus. -

The University of Arizona

Erskine Caldwell, Margaret Bourke- White, and the Popular Front (Moscow 1941) Item Type text; Electronic Dissertation Authors Caldwell, Jay E. Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 05/10/2021 10:56:28 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/316913 ERSKINE CALDWELL, MARGARET BOURKE-WHITE, AND THE POPULAR FRONT (MOSCOW 1941) by Jay E. Caldwell __________________________ Copyright © Jay E. Caldwell 2014 A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 2014 THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA GRADUATE COLLEGE As members of the Dissertation Committee, we certify that we have read the dissertation prepared by Jay E. Caldwell, titled “Erskine Caldwell, Margaret Bourke-White, and the Popular Front (Moscow 1941),” and recommend that it be accepted as fulfilling the dissertation requirement for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy. ________________________________________________ Date: 11 February 2014 Dissertation Director: Jerrold E. Hogle _______________________________________________________________________ Date: 11 February 2014 Daniel F. Cooper Alarcon _______________________________________________________________________ Date: 11 February 2014 Jennifer L. Jenkins _______________________________________________________________________ Date: 11 February 2014 Robert L. McDonald _______________________________________________________________________ Date: 11 February 2014 Charles W. Scruggs Final approval and acceptance of this dissertation is contingent upon the candidate’s submission of the final copies of the dissertation to the Graduate College. -

A Brief History of Fascist Lies

A Brief History of Fascist Lies Federico Finchelstein UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA PRESS A Brief History of Fascist Lies A Brief History of Fascist Lies Federico Finchelstein UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA PRESS University of California Press Oakland, California © 2020 by Federico Finchelstein Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Finchelstein, Federico, 1975– author. Title: A brief history of fascist lies / Federico Finchelstein. Description: Oakland, California : University of California Press, [2020] | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers: LCCN 2019052243 (print) | LCCN 2019052244 (ebook) | ISBN 9780520346710 (cloth) | ISBN 9780520975835 (epub) Subjects: LCSH: Fascism—History—20th century. Classification: LCC JC481 .F5177 2020 (print) | LCC JC481 (ebook) | DDC 320.53/3—dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019052243 LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019052244 Manufactured in the United States of America 28 27 26 25 24 23 22 21 20 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 A Lucia, Gabi, y Laura Contents Introduction 1 1. On Fascist Lies 11 2. Truth and Mythology in the History of Fascism 20 3. Fascism Incarnate 28 4. Enemies of the Truth? 33 5. Truth and Power 40 6. Revelations 49 7. The Fascist Unconscious 58 8. Fascism against Psychoanalysis 65 9. Democracy and Dictatorship 75 10. The Forces of Destruction 85 Epilogue: The Populist War against History 91 Acknowledgments 107 Notes 109 Index 135 Introduction What you’re seeing and what you’re reading is not what’s happening. DONALD J. TRUMP, 2018 Since then, a struggle between the truth and the lie has been taking place. -

Perceptions of the Holocaust in Contemporary Romania: Between Film and Television

William Totok the Romanian capital, which commemorates About the author: the persecution of Jews and Roma. William Totok, M.A., born 1951, lives as a Although in 2002 a government decree freelance writer in Berlin. He was a member (ratified in 2006 as a law) made Holocaust deni- of the International Commission to Investi- al, the glorification of war criminals, the public gate the Romanian Holocaust, which submit- dissemination of fascist symbols, and the estab- ted its final report in 2004, which came out lishment of fascist organizations and parties one year later in book form. Recent publica- into criminal offenses, in Romania there have tions: Episcopul, Hitler si Securitatea. Proce- sul stalinist împotriva “spionilor Vaticanului“ been no prosecutions against either Holocaust in România [The Bishop, Hitler, and the Se- deniers or extreme right-wing organizations. curitate: The Stalinist proceedings against the “Vatican Spies” in Romania], Iasi 2008; and Translation from the German by John Kenney the study “The Timeliness of the Past: The Fall of Nicolae Paulescu” in Peter Manu and Horia Bozdoghina, ed. Polemica Paulescu: sti- inta, politica, memorie [The Paulescu Polemic: Scholarship, Politics, Remembrance], Bucha- rest 2010. e-mail: [email protected] Perceptions of the Holocaust in Contemporary Romania: Between Film and Television by Victor Eskenasy, Frankfurt am Main n spite of the relatively large number of stu- widely popular public intellectuals, made Idies and collections of documents published known particularly by television, -

Yugoslavia As a Case Study

The Killing Fields, Ethnic Cleansing and Genocide in Europe: Yugoslavia as a Case Study by Hal Elliott Wert The Bloodlands: An Historical Overiew Ian Kershaw, in The End: The Defiance and Destruction of Hitler’s Germany, 1944-1945, recounts in great detail the horrific slaughter accompanying the end of the World War II in Europe, a tale told as well by Antony Beevor, Richard J. Evans, Max Hastings, and David Stafford, among others.1 Timothy Snyder in Bloodlands, a groundbreaking book about the atrocities committed by Stalin and Hitler between the World Wars and during World War II, broadens the perspective and the time frame. An especially forceful chapter recounts the massive ethnic cleansing of Germans and other ethnic groups that occurred near the end of that war under the auspices of the Soviet Red Army in order to establish ethnically pure nation states, for example, Poles in Poland, Ukrainians in the Soviet Ukraine, and Germans in a truncated Germany.2 The era of Stalin and Hitler was captured in the lyrics of a hit song recorded by Leonard Cohen entitled The Future: “The blizzard of the world has crossed the threshold, I see the future brother—it is murder.” For millions in Stalin’s grasp the “truth of Marxist dialectics” was brought home to them by the cold steel barrel of a pistol that parted the hair on the back of their heads. Momentarily each of those millions understood the meaning of being “on the wrong side of history” as they were rounded up, executed, and buried in mass unmarked graves just for being a member of a despised ethnic group. -

On Fascist Ideology

On Fascist Ideology Federico Finchelstein Comprendere e saper valutare con esattezza il nemico, significa possedere gia` una con- dizione necessaria per la vittoria. Antonio Gramsci1 Fascism is a political ideology that encompassed totalitarianism, state terrorism, imperialism, racism and, in the German case, the most radical genocide of the last century: the Holocaust. Fascism, in its many forms did not hesitate to kill its own citizens as well as its colonial subjects in its search for ideological and political closure. Millions of civilians perished on a global scale during the apogee of fascist ideologies in Europe and beyond. In historical terms, fascism can be defined as a movement and a regime. Emilio Gentile – who, with Zeev Sternhell and George Mosse,2 is the most insightful historian of fascism – presents fascism as a modern revolutionary phenomenon that was nationalist and revolution- ary, anti-liberal and anti-Marxist. Gentile also presents fascism as being typically organized in a militaristic party that had a totalitarian conception of state politics, an activist and anti- theoretical ideology as well as a focus on virility and anti-hedonistic mythical foundations. For Gentile a defining feature of fascism was its character as a secular religion which affirms the primacy of the nation understood as an organic and ethnically homogenous community. Moreover, this nation was to be hierarchically organized in a corporativist state endowed with a war-mongering vocation that searches for a politics of national expansion, potency and conquest. Fascism, in short, was not a mere reactionary ideology. Rather, fascism aimed at creating a new order and a new civilization.3 The word fascism derives from the Italian word fascio and refers to a political group (such as the political group lead by Giuseppe Garibaldi during the time of Italian unification.) Fascism also refers visually and historically to a Roman imperial symbol of authority. -

Fascism, Liberalism and Europeanism in the Political Thought of Bertrand

5 NIOD STUDIES ON WAR, HOLOCAUST, AND GENOCIDE Knegt de Jouvenel and Alfred Fabre-Luce Alfred and Jouvenel de in the Thought Political of Bertrand Liberalism andFascism, Europeanism Daniel Knegt Fascism, Liberalism and Europeanism in the Political Thought of Bertrand de Jouvenel and Alfred Fabre-Luce Fascism, Liberalism and Europeanism in the Political Thought of Bertrand de Jouvenel and Alfred Fabre-Luce NIOD Studies on War, Holocaust, and Genocide NIOD Studies on War, Holocaust, and Genocide is an English-language series with peer-reviewed scholarly work on the impact of war, the Holocaust, and genocide on twentieth-century and contemporary societies, covering a broad range of historical approaches in a global context, and from diverse disciplinary perspectives. Series Editors Karel Berkhoff, NIOD Thijs Bouwknegt, NIOD Peter Keppy, NIOD Ingrid de Zwarte, NIOD and University of Amsterdam International Advisory Board Frank Bajohr, Center for Holocaust Studies, Munich Joan Beaumont, Australian National University Bruno De Wever, Ghent University William H. Frederick, Ohio University Susan R. Grayzel, The University of Mississippi Wendy Lower, Claremont McKenna College Fascism, Liberalism and Europeanism in the Political Thought of Bertrand de Jouvenel and Alfred Fabre-Luce Daniel Knegt Amsterdam University Press This book has been published with a financial subsidy from the European University Institute. Cover illustration: Pont de la Concorde and Palais Bourbon, seat of the French parliament, in July 1941 Source: Scherl / Bundesarchiv Cover design: Coördesign, Leiden Typesetting: Crius Group, Hulshout Amsterdam University Press English-language titles are distributed in the US and Canada by the University of Chicago Press. isbn 978 94 6298 333 5 e-isbn 978 90 4853 330 5 (pdf) doi 10.5117/9789462983335 nur 686 / 689 Creative Commons License CC BY NC ND (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0) The author / Amsterdam University Press B.V., Amsterdam 2017 Some rights reserved. -

Schutzstaffel from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia

Create account Log in Article Talk Read Edit View history Schutzstaffel From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia "SS" redirects here. For other uses, see SS (disambiguation). Navigation The Schutzstaffel (German pronunciation: [ˈʃʊtsˌʃtafәl] ( listen), translated to Protection Main page Protection Squadron Squadron or defence corps, abbreviated SS—or with stylized "Armanen" sig runes) Contents Schutzstaffel was a major paramilitary organization under Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party (NSDAP). It Featured content began at the end of 1920 as a small, permanent guard unit known as the "Saal- Current events Schutz" (Hall-Protection)[1] made up of NSDAP volunteers to provide security for Nazi Random article Party meetings in Munich. Later in 1925, Heinrich Himmler joined the unit which had by Donate to Wikipedia then been reformed and renamed the "Schutz-Staffel". Under Himmler's leadership (1929–45), it grew from a small paramilitary formation to one of the largest and most [2] Interaction powerful organizations in the Third Reich. Built upon the Nazi ideology, the SS under SS insignia (sig runes) Himmler's command was responsible for many of the crimes against humanity during Help World War II (1939–45). The SS, along with the Nazi Party, was declared a criminal About Wikipedia organization by the International Military Tribunal, and banned in Germany after 1945. Community portal Recent changes Contents Contact page 1 Background SS flag 1.1 Special ranks and uniforms Toolbox 1.2 Ideology 1.3 Merger with police forces What links here 1.4 Personal control by Himmler Related changes 2 History Upload file 2.1 Origins Special pages 2.2 Development Permanent link 2.3 Early SS disunity Page information 3 Before 1933 Data item 3.1 1925–28 Cite this page 3.2 1929–31 3.3 1931–33 Print/export 4 After the Nazi seizure of power Adolf Hitler inspects the Leibstandarte SS Adolf Hitler on 4.1 1934–36 Create a book arrival at Klagenfurt in April 1938. -

Visualizing FASCISM This Page Intentionally Left Blank Julia Adeney Thomas and Geoff Eley, Editors

Visualizing FASCISM This page intentionally left blank Julia Adeney Thomas and Geoff Eley, Editors Visualizing FASCISM The Twentieth- Century Rise of the Global Right Duke University Press | Durham and London | 2020 © 2020 Duke University Press All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America on acid- free paper ∞ Designed by Julienne Alexander / Cover designed by Matthew Tauch Typeset in Minion Pro and Haettenschweiler by Copperline Books Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Eley, Geoff, [date] editor. | Thomas, Julia Adeney, [date] editor. Title: Visualizing fascism : the twentieth-century rise of the global right / Geoff Eley and Julia Adeney Thomas, editors. Description: Durham : Duke University Press, 2020. | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers:lccn 2019023964 (print) lccn 2019023965 (ebook) isbn 9781478003120 (hardback : acid-free paper) isbn 9781478003762 (paperback : acid-free paper) isbn 9781478004387 (ebook) Subjects: lcsh: Fascism—History—20th century. | Fascism and culture. | Fascist aesthetics. Classification:lcc jc481 .v57 2020 (print) | lcc jc481 (ebook) | ddc 704.9/49320533—dc23 lc record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019023964 lc ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019023965 Cover art: Thomas Hart Benton, The Sowers. © 2019 T. H. and R. P. Benton Testamentary Trusts / UMB Bank Trustee / Licensed by vaga at Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY. This publication is made possible in part by support from the Institute for Scholarship in the Liberal Arts, College of Arts and Letters, University of Notre Dame. CONTENTS ■ Introduction: A Portable Concept of Fascism 1 Julia Adeney Thomas 1 Subjects of a New Visual Order: Fascist Media in 1930s China 21 Maggie Clinton 2 Fascism Carved in Stone: Monuments to Loyal Spirits in Wartime Manchukuo 44 Paul D. -

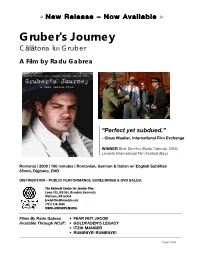

Gruber's Journey Press

☆ New Release – Now Available ☆ Gruber's Journey Călătoria lui Gruber A Film by Radu Gabrea “Perfect yet subdued.” - Claus Mueller, International Film Exchange WINNER Best Director (Radu Gabrea), 2009 Levante International Film Festival (Italy) Romania | 2008 | 100 minutes | Romanian, German & Italian w/ English Subtitles 35mm, Digibeta, DVD DISTRIBUTION - PUBLIC PERFORMANCE SCREENINGS & DVD SALES: The National Center for Jewish Film Lown 102, MS 053, Brandeis University Waltham, MA 02454 [email protected] (781) 736-8600 WWW.JEWISHFILM.ORG Films By Radu Gabrea • FEAR NOT JACOB Available Through NCJF: • GOLDFADEN’S LEGACY • ITZIK MANGER • RUMENYE! RUMENYE! Page 1 of 4 Gruber's Journey A Film by Radu Gabrea Romania | 2008 | 100 minutes | Fiction Feature Film Romanian, German & Italian w/ English Subtitles 35mm; Digibeta; DVD Festivals & Broadcast FESTIVAL SCREENINGS • San Francisco Jewish Film Festival 2010 (upcoming) • Caracas (Venezuela) Jewish Film Festival 2010 (upcoming) • New York Jewish Film Festival, Lincoln Center 2010 • Levante International Film Festival (Italy) 2009 • Vancouver Jewish Film Festival 2009 • Philadelphia Jewish Film Festival 2009 • Contra Costa International Jewish Film Festival 2009 • Silicon Valley Jewish Film Festival 2009 • European Union Film Festival, Chicago 2009 • Atlanta Jewish Film Festival 2009 • Toronto Jewish Film Festival 2009 • Romanian Film Festival, New York 2008 • Klezmer Festival Buenos Aires, Argentina 2008 • Jerusalem Film Festival 2008 • Transylvania International Film Festival 2008 Synopsis In June 1941, Curzio Malaparte (Florin Piersic Jr.), an Italian journalist and member of the Fascist party, arrives in the Romanian city of Iasi on the way to cover the Russian front for an Italian newspaper. Suffering from severe allergies, he is referred to Josef Gruber (Marcel Iureş), a local Jewish doctor.