Culture, Power, and Security

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Catalogue of the Alumni of the University of Pennsylvania

^^^ _ M^ ^3 f37 CATALOGUE OF THE ALUMNI OF THE University of Pennsylvania, COMPRISING LISTS OF THE PROVOSTS, VICE-PROVOSTS, PROFESSORS, TUTORS, INSTRUCTORS, TRUSTEES, AND ALUMNI OF THE COLLEGIATE DEPARTMENTS, WITH A LIST OF THE RECIPIENTS OF HONORARY DEGREES. 1749-1877. J 3, J J 3 3 3 3 3 3 3', 3 3 J .333 3 ) -> ) 3 3 3 3 Prepared by a Committee of the Society of ths Alumni, PHILADELPHIA: COLLINS, PRINTER, 705 JAYNE STREET. 1877. \ .^^ ^ />( V k ^' Gift. Univ. Cinh il Fh''< :-,• oo Names printed in italics are those of clergymen. Names printed in small capitals are tliose of members of the bar. (Eng.) after a name signifies engineer. "When an honorary degree is followed by a date without the name of any college, it has been conferred by the University; when followed by neither date nor name of college, the source of the degree is unknown to the compilers. Professor, Tutor, Trustee, etc., not being followed by the name of any college, indicate position held in the University. N. B. TJiese explanations refer only to the lists of graduates. (iii) — ) COEEIGENDA. 1769 John Coxe, Judge U. S. District Court, should he President Judge, Court of Common Pleas of Philadelphia. 1784—Charles Goldsborough should he Charles W. Goldsborough, Governor of Maryland ; M. C. 1805-1817. 1833—William T. Otto should he William T. Otto. (h. Philadelphia, 1816. LL D. (of Indiana Univ.) ; Prof, of Law, Ind. Univ, ; Judge. Circuit Court, Indiana ; Assistant Secre- tary of the Interior; Arbitrator on part of the U. S. under the Convention with Spain, of Feb. -

Hclassification

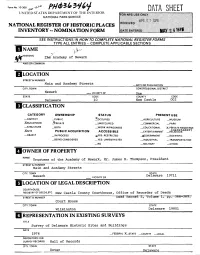

Form No. 10-300 ^O' 1 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES INVENTORY -- NOMINATION FORM SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOWTO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS TYPE ALL ENTRIES -- COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS I NAME HISTORIC .The"' Academy of Newark AND/OR COMMON LOCATION STREET & NUMBER Main and Academy Streets -NOT FOR PUBLICATION CITY. TOWN CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT Newark _ VICINITY OF One STATE CODE COUNTY CODE Delaware 10 New Castle 002 HCLASSIFICATION CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE —DISTRICT —PUBLIC .^OCCUPIED —AGRICULTURE —MUSEUM .XBUILDING(S) _3>RIVATE —UNOCCUPIED —COMMERCIAL —PARK —STRUCTURE —BOTH —WORK IN PROGRESS —EDUCATIONAL X-PRIVATE RESIDENCE JiSITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE —ENTERTAINMENT _ REGifc^S 6 —OBJECT _ INPROCESS -XYES: RESTRICTED -^GOVERNMENT —SCIENTIFIC —BEING CONSIDERED — YES: UNRESTRICTED —INDUSTRIAL —TRANSPORTATION _NO —MILITARY —OTHER: OWNER OF PROPERTY NAME Trustees of the Academy of Newark, Mr. James H. Thompson, President STREET & NUMBER Main and Academy Streets CITY, TOWN Delaware 19711 Newark VICINITY OF LOCATION OF LEGAL DESCRIPTION COURTHOUSE, REGISTRY OF DEEDS, ETC. New Castle County Courthouse, Office of Recorder of Deeds STREET & NUMBER Deed Record Z , Volume 366 369, Court House CITY, TOWN STATE Wilmington Delaware 19801 REPRESENTATION IN EXISTING SURVEYS TITLE Survey of Delaware Historic Sites and Buildings DATE 1974 —FEDERAL X_STATE —COUNTY —LOCAL CITY, TOWN STATE Dover Delaware DESCRIPTION CONDITION CHECK ONE CHECK ONE —EXCELLENT —DETERIORATED —UNALTERED X.ORIGINALSITE 1LGOOD —RUINS FALTERED —MOVED DATE. _FAIR —UNEXPOSED DESCRIBE THE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL (IF KNOWN) PHYSICAL APPEARANCE Academy Square/ at the southeast corner of Main and Academy Streets, is a park, on the south side of which is the Academy of Newark building. -

A Political Biography of John Witherspoon from 1723-1776

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 1979 A political biography of John Witherspoon from 1723-1776 John Thomas anderson College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the European History Commons, and the Social and Behavioral Sciences Commons Recommended Citation anderson, John Thomas, "A political biography of John Witherspoon from 1723-1776" (1979). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539625075. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-tdv7-hy77 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A POLITICAL BIOGRAPHY OF JOHN WITHERSPOON * L FROM 1723 TO 1776 A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Department of History The College of William and Mary in Virginia In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts *y John Thomas Anderson APPROVAL SHEET This thesis is submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Author Approved, September 1979 John Michael McGiffert (J ^ j i/u?wi yybirvjf \}vr James J. Thompson, Jr. To my parents TABLE OF CONTENTS Page DEDICATION....................... ill TABLE OF CONTENTS ..................................... iv ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ............................................... v ABSTRACT........... vi INTRODUCTION................. 2 CHAPTER I. "OUR NOBLE, VENERABLE, REPUBLICAN CONSTITUTION": JOHN WITHERSPOON IN SCOTLAND, 1723-1768 . ............ 5 CHAPTER II. "AN EQUAL REPUBLICAN CONSTITUTION": WITHERSPOON IN NEW JERSEY, 1768-1776 37 NOTES . -

Autobiography of Benjamin Franklin 25

YPi AAAAAAJL 'imjij i=W AurCS'.ORAPHYOF BENJAMIN FRANKLIN t: > ' '^ \^^ -^ • ^JJ^I yfv Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2007 with funding from IVIicrosoft Corporation http://www.archive.org/details/autobiographyofb00fran5 V Autobiography or Benjaa\in Tranklin Chicago W. B. CONKEY COMPANY THE IIW YORK PUBLIC LIBRARY gG819^B ASTCR, LEN&X AND TfLOm HtfUNDAliONS B 1044 L LIFE or DR. FRANKLIN / My deab Sok, I HAVE amused myself with collecting some little anecdotes of my family. You may re- member the inquiries I made, when you were with me in England, among such of my rela- tions as were then living ; and the journey J undertook for that purpose. To be ac- quainted with the particulars of my parent- age and life, many of which are unknown to you, I flatter myself will afford the same pleasure to you as to me. I shall relate them upon paper : it will be an agreeable employ- ment of a week's uninterrupted leisure, which I promise myself during my present retire- ment in the country. There are also other motives which induce me to the undertaking. 4 3YS5 a 4 LI Ft: OF DR.. FRANKLIlSf. From the bosom of poverty and obscurity, in which I drew my first breath, and spent my earliest years, I have raised myself to a state of opulence and to some degree of celebrity in the world. A constant good fortune has attended me through every period of life to my present advanced age ; and my descend- ants may be desirous of learning what were the means of which I made use, and which, thanks to the assisting hand of Providence, have proved so eminently successful. -

At the Instance of Benjamin Franklin: a Brief History of the Library Company of Philadelphia

At the Instance of Benjamin Franklin: A Brief History of The Library Company of Philadelphia On July 1, 1731, Benjamin Franklin and a number of his fellow members of the Junto drew up "Articles of Agreement" to found a library. The Junto was a discussion group of young men seeking social, economic, intellectual, and political advancement. When they foundered on a point of fact, they needed a printed authority to settle the divergence of opinion. In colonial Pennsylvania at the time there were not many books. Standard English reference works were expensive and difficult to obtain. Franklin and his friends were mostly mechanics of moderate means. None alone could have afforded a representative library, nor, indeed, many imported books. By pooling their resources in pragmatic Franklinian fashion, they could. The contribution of each created the book capital of all. Fifty subscribers invested forty shillings each and promised to pay ten shillings a year thereafter to buy books and maintain a shareholder's library. Thus "the Mother of all American Subscription Libraries" was established. A seal was decided upon with the device: "Two Books open, Each encompass'd with Glory, or Beams of Light, between which water streaming from above into an Urn below, thence issues at many Vents into lesser Urns, and Motto, circumscribing the whole, Communiter Bona profundere Deum est." This translates freely: "To pour forth benefits for the common good is divine." The silversmith Philip Syng engraved the seal. The first list of desiderata to stock the Tin Suggestion shelves was sent to London on March 31, 1732, and by autumn that Box, ca. -

Historical Sketch of the Synod of Philadelphia

^ * APR 23 1932 OF THE Synod of Philadelphia. By R. M. PATTEBSON, PASTOR OF THE SOUTH PRESBYTERIAN CHURCH, PHILADELPHIA J AND BIOGRAPHICAL SKETCHES OF istiiigutski) ^Umbers of tbe f poo of ^hitoMphw. y By the Rev. ROBERT DAVIDSON, D.D. PHILADELPHIA : PRESBYTERIAN BOARD OF PUBLICATION, 1334 CHESTNUT STREET. Entered according to Act of Congress, in the year 1876, by THE TRUSTEES OF THE PRESBYTERIAN BOARD OF PUBLICATION, In the Office of the Librarian of Congress, at Washington. Westcott & Thomson, Stereotypers and Ekctrolypers, Philada. : : : ACTION OF THE SYNOD OF PHILADELPHIA. The following citations from the minutes of the Synod of Philadelphia will show the circumstances under which the papers embraced in this volume were prepared and are published Saturday, October 17, 1874. The committee on centennial exercises presented the following report, which was accepted and adopted The committee appointed to consider and report upon the question of centennial exercises during the sessions of Synod the coming year begs leave to recommend as follows 1. That the afternoon following the organization of the Synod be spent in services commemorative of God's providential deal- ings with this body during the last century, the particular order of these services to be arranged by the committee on devotional exert' 2. That these exercises consist of the reading of appropriate scriptures, of prayer and praise, the reading of the papers specified below, and voluntary addresses by members of the Synod. 3. That the Rev. R. M. Patterson be appointed to present a brief historical sketch of the Synod during the past century. 4. That the Rev. -

A Portrait of the First Continental Congress

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 2009 Fifty gentlemen total strangers: A portrait of the First Continental Congress Karen Northrop Barzilay College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the American Studies Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Barzilay, Karen Northrop, "Fifty gentlemen total strangers: A portrait of the First Continental Congress" (2009). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539623537. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-61q6-k890 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Fifty Gentlemen Total Strangers: A Portrait of the First Continental Congress Karen Northrop Barzilay Needham, Massachusetts Master of Arts, College of William and Mary, 1998 Bachelor of Arts, Skidmore College, 1996 A Dissertation presented to the Graduate Faculty of the College of William and Mary in Candidacy for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy American Studies Program The College of William and Mary January 2009 © 2009 Karen Northrop Barzilay APPROVAL PAGE This Dissertation is submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy ~ilayd Approved by the Committee, October, 2008 Commd ee Chair Professor Robert A Gross, History and American Studies University of Connecticut Professor Ronald Hoffman, History Director, Omohundro Institute of Early American History and Culture The College of William and Mary Associate Professor Karin Wuff, History and encan Studres The College of William and Mary ABSTRACT PAGE When news of the Coercive Acts reached the mainland colonies ofBritish North America in May 177 4, there was no such thing as a Continental Congress. -

The Newark Academy of Delaware in Colonial Days1 by George H

THE NEWARK ACADEMY OF DELAWARE IN COLONIAL DAYS1 BY GEORGE H. RYDEN, PH.D. University of Delaware HE present University of Delaware had its inception in a T little institution of colonial days known as Newark Academy. This academy was a child of the Presbyterian church, and for many years its trustees, clerical and lay, were for the most part, if not altogether, of the Presbyterian persuasion. It was preceded by only one other Presbyterian school, namely, the famous "Log College", founded by the Reverend William Tennent, a well- trained Anglican clergyman, who, upon his arrival in Philadelphia from overseas, joined the Presbyterian communion. Tennent established his school about 1726 with a view to meeting a great need for preachers of the gospel among the Scotch-Irish immi- grants. He located it north of Philadelphia at the Forks of the Neshaminy River. Here Tennent's four sons were trained for the ministry; likewise many other men who served the Presby- terian church faithfully in the older established congregations as well as upon the frontier mission fields of Pennsylvania, Maryland, and Virginia. The demand for ministers, however, still exceeded the supply, and the temptation was always strong in the various presbyteries to license as preachers pious laymen equipped with little or no cultural or theological training. As is usually the case among struggling congregations in a new country, very little distinction was made between a trained or an untrained clergyman. If the man could preach, little more was asked of him, excepting that he should be fully cognizant of the difficulties of life confronting his people, and adapt himself accordingly. -

Presbyterian Church of Philadelphia

T H E Presbyter1an Church IN PHILADELPHIA A CAMERA AND PEN SKETCH OE EACH PRESBYTERIAN CHURCH AND INSTITUTION IN THE CITY COMPILED AND EDITED us- Rev. \VM. P. WHITE, D. D. ASH WILLIAM H. SCOTT WITH A PREI-'AIORY NOTE BY Rf.v. WILLIAM C. CATTELL, D. D., LI,. D. President of the Presbyterian Historical Society AND AN INTRODUCTION BY Rev. WILLARD M. RICE, D. D. Stated Clerk of the Philadelphia Presbytery PHILADELPHIA ALLEN, LANE & SCOTT PUBLISHERS "895 f }" ■ - •■-' ■ 7WT. ,(;;:. / ENTERED, ACCORDING TO ACT OF CONGRESS, IN THE YEAR 1B95, By WILLIAM H. SCOTT, In the Office of vhk Librarian of Congress, at Washington, D. C. tress OF ALLEN, LANE * SCOTT. PHILADELPHIA. Rev. Albert Barnes. Rev. Thomas Brainerd. Rev. William P, Breed. Rev. Henry A. Boardman. Rev. elias r. Beadle. John A. Brown. Mathias W. Baldwin. Seven Philadelphia Presrytkrian TVs. 1 *.J\J\i■■J 4 XvJ PREFATORY NOTE. Bv Rev. WILLIAM C. CATTELL, D. D., LL. D., President of the Presbyterian Historical Society. Any publication bearing upon Presbyterianism has more or less value to all who love its history, doctrine, polity, and progress, but the present volume will be more than usually prized. It is a unique contribution to the history of a Church known for its sterling, intel ligent, and faithful eldership as well as for its able and consecrated ministry. The book is a memorial of what the Vresbyterian Church has accomplished in Philadelphia, but represents more than a local interest. It has a wider reach as a forerunner and model of what liberal laymen, historically inclined, may do for Presbyterianism in all its large centres, in the way of giving to the public, in impressive out line, the noble work which our Church has accomplished in their respec tive localities. -

Names of Buildings and Locations

Names of Buildings and Locations Notes Data current through September 2020. All buildings and locations are situated in Newark unless otherwise indicated. Buildings known only by street addresses are not included. Not included within this list are the following: rooms, wings, and other named portions of buildings; ships and research vessels; grounds other than named athletic fields; parking garages and facilities; houses used for faculty and staff rentals; fraternity and sorority houses not built by the University of Delaware itself; buildings (named or otherwise) no longer extant, owned, or leased by the University of Delaware; buildings used by campus religious ministries unless named; unnamed agricultural outbuildings and facilities; unnamed facilities buildings and plants. Dates refer to the adoption of naming resolutions for buildings, not to construction, openings, or dedications of those buildings. Name of Building or Date of Naming Notes Location Resolution Building not named by resolution. By terms of settlement with the Trustees of the Academy of Newark in the Academy Building N/A Delaware Court of Chancery in 1975, the University of Delaware agreed to name the building as the “Academy of Newark Building” as part of the completion of transfer of ownership of the building. Building named by resolution for Francis Alison, prominent colonial Presbyterian clergyman and founder of a Alison Hall 1953 free school in New London, Pennsylvania in 1743, which subsequently developed into the Academy of Newark and the University of Delaware. Building is an addition to Alison Hall; not named by resolution other than that adopted in 1953 for the original Alison Hall West N/A portion of Alison Hall (see Alison Hall above). -

The 'Philadelaware Ans: *J1 Study in the I^Elations ^Between Philadelphia and 'Delaware in the J^Ate Eighteenth Qentury

The 'Philadelaware ans: *J1 Study in the I^elations ^Between Philadelphia and 'Delaware in the J^ate Eighteenth Qentury " "W~ ~w AVEING made an appointment three weeks ago to go to I 1 Philadelphia with Mr. Abraham Winekoop I fixt on this JL A day to set of—before I was quit Ready t went Round the Town To bid my friends fare well/' So Thomas Rodney began, on September 14, 1769, his journal of a trip from Dover to Philadelphia. It was, of course, a considerable journey which he was undertaking. Philadelphia was three days to the north—a glamorous cosmopolis which* would afford young Rod- ney an endless round of tea, grog, and coffee drinking with friends, of visiting the ships on the river, and of playing billiards in Spring Garden. But such pleasant dalliance soon exhausted the youth and he hastened back to the Lower Counties and to a tryst with his sweetheart.2 The time of Rodney's trip and the formality of his farewells indi- cate the relative isolation of central Delaware in his day. Compared with the 1940's, when one might even commute from Dover to Philadelphia, the isolation was indeed great. Most especially was this true of Kent and Sussex counties. New Castle County, northern- most of the three that comprise Delaware, was fortunate in lying athwart the main land route of travel from Philadelphia and the North to Baltimore and the South. Through Kent and Sussex, however, almost no one found his way, unless he was interested in 1 From an address delivered before the Pennsylvania Historical Junto in Washington on November 24, 1944. -

Ulster Pennsylvania Ulster-Scots and &‘The Keystone State’ Ulster-Scots and ‘The Keystone State’

Ulster Pennsylvania Ulster-Scots and &‘the Keystone State’ Ulster-Scots and ‘the Keystone State’ Introduction The earliest Ulster-Scots emigrants to ‘the New World’ tended to settle in New England. However, they did not get on with the Puritans who controlled government there and whom they came to regard as worse than the Church of Ireland authorities they had left behind in Ulster. For example, when the Ulster-Scots settlers in Worcester, Massachusetts, tried to build a Presbyterian meeting house, their Puritan neighbours tore it down. Thus, future Ulster- Scots emigrant ships headed further south to Newcastle, Delaware, and Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, rather than the ports of New England. Pennsylvania was established by William Penn in 1682 with two objectives: to enrich himself and as a ‘holy experiment’ in establishing complete religious freedom, primarily for the benefit of his fellow Quakers. George Fox, the founder of the Quakers, had visited the region in 1672 and was mightily impressed. As the historian D.H. Fischer has observed in Albion’s Seed: Four British Folkways in America (New York, 1991): William Penn was a bundle of paradoxes - an admiral son’s who became a pacifist, an undergraduate at Oxford’s Christ Church who became a pious Quaker, a member of Lincoln’s Inn who became an advocate of arbitration, a Fellow of the Royal Society who despised pedantry, a man of property who devoted himself to the poor, a polished courtier who preferred the plain style, a friend of kings who became a radical Whig, and an English gentleman who became one of Christianity’s great spiritual leaders.