Voluntary Associations for Propagating the Enlightenment in Philadelphia 1727-1776

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Maryland Historical Magazine, 1961, Volume 56, Issue No. 2

MARYLAND HISTORICAL MAGAZINE VOL. 56, No. 2 JUNE, 1961 CONTENTS PAGE Sir Edmund Plowden's Advice to Cecilius Calvert Edited by Edward C. Carter, II 117 The James J. Archer Letters. Part I Edited by C. ^. Porter Hopkins 125 A British Officers' Revolutionary War Journal, 1776-1778 Edited by S. Sydney Bradford 150 Religious Influences on the Manumission of Slaves Kenneth L. Carroll 176 Sidelights 198 A Virginian and His Baltimore Diary: Part IV Edited by Douglas H. Gordon Reviews of Recent Books 204 Walsh, Charleston's Sons of Liberty: A Study of the Artisans, 1763- 1789, by Richard B. Morris Manakee, Maryland in the Civil War, by Theodore M. Whitfield Hawkins, Pioneer: A History of the Johns Hopkins University, 1874- 1889, by George H. Callcott Tonkin, My Partner, the River: The White Pine Story on the Susquehanna, by Dorothy M. Brown Hale, Pelts and Palisades: The Story of Fur and the Rivalry for Pelts in Early America, by R. V. Truitt Beitzell, The Jesuit Missions of St. Mary's County, Maryland, by Rev. Thomas A. Whelan Rightmyer, Parishes of the Diocese of Maryland, by George B. Scriven Altick, The Scholar Adventurers, by Ellen Hart Smith Levin, The Szolds of Lombard Street: A Baltimore Family, 1859- 1909, by Wilbur H. Hunter, Jr. Hall, Edward Randolph and the American Colonies, 1676-1703, by Verne E. Chatelain Gipson, The British Isles and the American Colonies: The Southern Plantations, 1748-1754, by Paul R. Locher Bailyn, Education in the Forming of American Society, by S. Sydney Bradford Doane, Searching for Your Ancestors: The How and Why of Genealogy, by Gust Skordas Notes and Queries 224 Contributors 228 Annual Subscription to the Magazine, $4.00. -

The Protocols of Indian Treaties As Developed by Benjamin Franklin and Other Members of the American Philosophical Society

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Departmental Papers (Religious Studies) Department of Religious Studies 9-2015 How to Buy a Continent: The Protocols of Indian Treaties as Developed by Benjamin Franklin and Other Members of the American Philosophical Society Anthony F C Wallace University of Pennsylvania Timothy B. Powell University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/rs_papers Part of the Diplomatic History Commons, Religion Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Wallace, Anthony F C and Powell, Timothy B., "How to Buy a Continent: The Protocols of Indian Treaties as Developed by Benjamin Franklin and Other Members of the American Philosophical Society" (2015). Departmental Papers (Religious Studies). 15. https://repository.upenn.edu/rs_papers/15 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/rs_papers/15 For more information, please contact [email protected]. How to Buy a Continent: The Protocols of Indian Treaties as Developed by Benjamin Franklin and Other Members of the American Philosophical Society Abstract In 1743, when Benjamin Franklin announced the formation of an American Philosophical Society for the Promotion of Useful Knowledge, it was important for the citizens of Pennsylvania to know more about their American Indian neighbors. Beyond a slice of land around Philadelphia, three quarters of the province were still occupied by the Delaware and several other Indian tribes, loosely gathered under the wing of an Indian confederacy known as the Six Nations. Relations with the Six Nations and their allies were being peacefully conducted in a series of so-called “Indian Treaties” that dealt with the fur trade, threats of war with France, settlement of grievances, and the purchase of land. -

Fire at Rehoboth, Delaware Closed So That Teachers and Pupils Might an Hour

ADVERTISING IN OUR COLUMNS INVARIABLY BRINGS THE BEST RESULTS Mfc SOMMERSET HERALD ••»•. PRINCESS ANNE, MD., TUESDAY, NOVEMBER 26, 1912. VoL XV-No. IS 1,000 KILLED BY A QUAKE DEMOCRATS CELEBRATE 'WIPED OUT BY TIDAL WAVE' FREE DELIVERY CARRIER A TEttRIFICHAIL STORM CHANGES OF PROPERTY Every Building in a Mexican Two Jamaica Towns Destroyed Palls Hangs Over Wilmingteft Number of Deeds Recorded at City Demolished A Large Gathering In Princes* and Thousands Perish From Princess Anne Poetoffice And Torrents of Rain Fall the Office of the Clerk of the Late reports from the State of Mex Anne Last Tuesday A great tidal wave is reported to After December 1st A terrific storm broke over Wihning- ico received Friday plaee the number As announced in our last issue, the have practically wiped out the town of Beginning December 1st experimen ton at 8 o'clock Sunday morning and Court Last Week of dead as a resnlt of Tuesday's earth Savanna la Mar, on the southwest coast, Democratic parade came off on Tuesday tal delivery of all mail matter by car many persons were badly scared. Tile Robert F. Maddox from James E. quake at more than 1,000. Every build last on .schedule time and i.i every re and Lucea, on the northwest coast of Dashiell, collector of State and County rier,' will be instituted at the Princess air became still and the day was turned ing in the city of Acambay was demol spect was a great success. The day was Jamaica. Forty- two persons were killed taxes, two and one-half acres of land in Anne postofflce, under the following ished. -

DLA Piper and the Baltimore Community ______213

THE POLICE DEPARTMENT OF BALTIMORE CITY MONITORING APPLICATION CONTENTS 32. Executive Summary: _____________________________________________________________ 1 33. Scope of Work: ________________________________________________________________ 12 34. Personnel and Current Time Commitments: __________________________________________ 20 35. Qualifications: _________________________________________________________________ 23 36. Prior Experience and References: _________________________________________________ 46 37. Budget: ______________________________________________________________________ 52 38. Collaboration and Cost Effectiveness: ______________________________________________ 53 39. Potential Conflicts of Interest: _____________________________________________________ 54 Appendix A. Proposed Budget _______________________________________________________ 57 Appendix B. Team Biographies _______________________________________________________ 60 Appendix C. DLA Piper and the Baltimore Community ____________________________________ 213 The Police Department of Baltimore City Monitoring Application June 2017 32. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY: A brief description of each member of the candidate’s team; relevant experience of the team members; any distinguishing skills or experiences; and a summary of the proposed budget. Our Approach The history of Baltimore reflects the history of the United States. From the Civil War to the fight for civil rights, this City we love has played a pivotal role in the struggles that have shaped our nation. But those -

Dean's Book(Final)

Centuries of Leadership: Deans of the University of Maryland School of Medicine Item Type Book Authors University of Maryland, Baltimore. School of Medicine Keywords University of Maryland, Baltimore. School of Medicine--History; Deans (Education) Download date 26/09/2021 05:27:38 Item License https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10713/4797 CENTURIES OF LEADERSHIP Deans of the University of Maryland School of Medicine 2000 900 1 800 1 C ONTENTS Deans 3 John Beale Davidge 4 Nathaniel Potter 5 Elisha DeButts 6 William Gibson 7 Richard Wilmot Hall 8 Maxwell McDowell 9 Granville Sharp Pattison 10 Nathan Ryno Smith 11 Samuel Baker 12 Eli Geddings 13 Robley Dunglison 14 Samuel George Baker 15 William E.A. Aikin 16 Samuel Chew 17 George Warner Miltenberger 18 Julian John Chisolm 19 Samuel Claggett Chew 20 Louis McLane Tiffany 21 Jacob Edwin Michael 22 Isaac Edmondson Atkinson 23 Robert Dorsey Coale 24 Charles Wellman Mitchell 25 Arthur M. Shipley 26 James M.H. Rowland 27 Robert Urie Patterson 28 H. Boyd Wylie 29 William Spencer Stone 30 John H. Moxley III 31 John Murray Dennis 32 Donald E. Wilson I NTRODUCTION Centuries of Leadership This book, presented with pride in the past and confidence in the future, honors the historic milestones in leadership of the University of Maryland School of Medicine over the past two centuries. During the deans’ tenures innumerable accomplishments and medical “firsts” were achieved. Each dean has made his own profound impression on the School, as well as the city and state the institution has served for nearly two hundred years. -

Brochure Design by Communication Design, Inc., Richmond, VA 8267 Main Street Destinations Like Chestertown, Port Deposit, Bel Air, Ellicott City, WASHINGTON, D.C

BALTIMOREST. P . R ESI . Druid Hill Park . 1 . D UL ST . E ST NT PENNSYLV ANIA PA WATER ST. ARD ST S VERT ST AW T 25 45 147 . EUT SAINT HOW HOPKINS PL LOMBARD ST. CHARLES ST CAL SOUTH ST MARKET PL M ASON AND DIXON LINE S . 83 U Y ST 273 PRATTST. COMMERCE ST GA S NORTH AVE. 1 Q Emmitsburg Greenmount 45 ST. U Cemetery FAWN E 1 H . T S A T H EASTERN AVE. N G USS Constellation I Union Mills L N SHARP ST CONWAYST. A Manchester R Taneytown FLEET ST. AY I Washington Monument/ Camden INNER V 1 E Mt. Vernon Place 97 30 25 95 Station R MONUMENT ST. BROADW HARBOR President Maryland . Street 27 Station LANCASTER ST. Historical Society . ORLEANS ST. ERT ST T . S Y 222 40 LV A Thurmont G Church Home CA Susquehanna Mt. Clare and Hospital KEY HWY Battle Monument 140 BALTIMORE RIOT TRAIL State Park Port Deposit ELKTON Mansion BALTIMORE ST. CHARLES ST (1.6-mile walking tour) 7 LOMBARD ST. Federal Hill James Archer L 77 Birthplace A PRATT ST. Middleburg Patterson P I Old Frederick Road D 40 R Park 138 U M (Loy’s Station) . EASTERN AVE. E R CONWAY ST. D V Mt. Clare Station/ B 137 Hereford CECIL RD ST USS O T. S I VE. FLEET ST. T 84 24 1 A B&O Railroad Museum WA O K TS RIC Constellation Union Bridge N R DE Catoctin S Abbott F 7 E HO FR T. WESTMINSTER A 155 L Monkton Station Furnance LIGH Iron Works L T (Multiple Trail Sites) S 155 RD 327 462 S 31 BUS A Y M 1 Federal O R A E K I Havre de Grace Rodgers R Hill N R S D T 22 Tavern Perryville E 395 BALTIMORE HARFORD H V K E Community Park T I Y 75 Lewistown H New Windsor W Bel Air Court House R R Y 140 30 25 45 146 SUSQUEHANNA O K N BUS FLATS L F 1 OR ABERDEEN E T A VE. -

Catalogue of the Alumni of the University of Pennsylvania

^^^ _ M^ ^3 f37 CATALOGUE OF THE ALUMNI OF THE University of Pennsylvania, COMPRISING LISTS OF THE PROVOSTS, VICE-PROVOSTS, PROFESSORS, TUTORS, INSTRUCTORS, TRUSTEES, AND ALUMNI OF THE COLLEGIATE DEPARTMENTS, WITH A LIST OF THE RECIPIENTS OF HONORARY DEGREES. 1749-1877. J 3, J J 3 3 3 3 3 3 3', 3 3 J .333 3 ) -> ) 3 3 3 3 Prepared by a Committee of the Society of ths Alumni, PHILADELPHIA: COLLINS, PRINTER, 705 JAYNE STREET. 1877. \ .^^ ^ />( V k ^' Gift. Univ. Cinh il Fh''< :-,• oo Names printed in italics are those of clergymen. Names printed in small capitals are tliose of members of the bar. (Eng.) after a name signifies engineer. "When an honorary degree is followed by a date without the name of any college, it has been conferred by the University; when followed by neither date nor name of college, the source of the degree is unknown to the compilers. Professor, Tutor, Trustee, etc., not being followed by the name of any college, indicate position held in the University. N. B. TJiese explanations refer only to the lists of graduates. (iii) — ) COEEIGENDA. 1769 John Coxe, Judge U. S. District Court, should he President Judge, Court of Common Pleas of Philadelphia. 1784—Charles Goldsborough should he Charles W. Goldsborough, Governor of Maryland ; M. C. 1805-1817. 1833—William T. Otto should he William T. Otto. (h. Philadelphia, 1816. LL D. (of Indiana Univ.) ; Prof, of Law, Ind. Univ, ; Judge. Circuit Court, Indiana ; Assistant Secre- tary of the Interior; Arbitrator on part of the U. S. under the Convention with Spain, of Feb. -

William Reese Company

William Reese Company Rare Books, Americana, Literature & Pictorial Americana 409 Temple Street New Haven, Connecticut 06511 203 / 789 · 8081 fax: 203 / 865 · 7653 e-mail: [email protected] web: www.reeseco.com Click on blue links to view complete Bulletin 21: American Cartography descriptions of the items and additional images where applicable. A Landmark American Map, Printed by Benjamin Franklin 1. Evans, Lewis: GEOGRAPHICAL, HISTORICAL, POLITICAL, PHILOSOPHICAL AND MECHANICAL ESSAYS. THE FIRST, CONTAINING AN ANALYSIS OF A GENERAL MAP OF THE MIDDLE BRITISH COLONIES IN AMERICA. Philadelphia: B. Franklin and D. Hall, 1755. Folding handcolored engraved map, 20¾ x 27¼ inches. Map backed on linen. Text: iv, 32pp. Quarto. Full tan polished tree calf by Riviere, red morocco label, a.e.g. Scattered light foxing. Very good. One of the most important maps of the British colonies done prior to that time, and its publication was a milestone in the development of Independence, a landmark in American cartography and an impor- printing arts in the colonial period”—Schwartz & Ehrenberg. tant Franklin printing. “The map is considered by historians to be the Evans’ map, which drew from his original surveys and Fry and Jef- most ambitious performance of its kind undertaken in America up to ferson’s 1753 map of Virginia, acknowledges French claims to all lands northwest of St. Lawrence Fort, resulting in criticism from New York. description of the Ohio country, and gives a good description of Despite the controversy, Evans’s work was very popular (there were the Carolina back country. The map was the authority for settling eighteen editions between 1755 and 1814), and was famously used by boundary disputes in the region. -

Hclassification

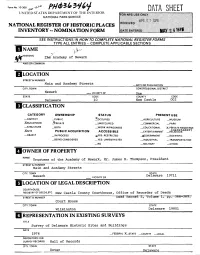

Form No. 10-300 ^O' 1 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES INVENTORY -- NOMINATION FORM SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOWTO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS TYPE ALL ENTRIES -- COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS I NAME HISTORIC .The"' Academy of Newark AND/OR COMMON LOCATION STREET & NUMBER Main and Academy Streets -NOT FOR PUBLICATION CITY. TOWN CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT Newark _ VICINITY OF One STATE CODE COUNTY CODE Delaware 10 New Castle 002 HCLASSIFICATION CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE —DISTRICT —PUBLIC .^OCCUPIED —AGRICULTURE —MUSEUM .XBUILDING(S) _3>RIVATE —UNOCCUPIED —COMMERCIAL —PARK —STRUCTURE —BOTH —WORK IN PROGRESS —EDUCATIONAL X-PRIVATE RESIDENCE JiSITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE —ENTERTAINMENT _ REGifc^S 6 —OBJECT _ INPROCESS -XYES: RESTRICTED -^GOVERNMENT —SCIENTIFIC —BEING CONSIDERED — YES: UNRESTRICTED —INDUSTRIAL —TRANSPORTATION _NO —MILITARY —OTHER: OWNER OF PROPERTY NAME Trustees of the Academy of Newark, Mr. James H. Thompson, President STREET & NUMBER Main and Academy Streets CITY, TOWN Delaware 19711 Newark VICINITY OF LOCATION OF LEGAL DESCRIPTION COURTHOUSE, REGISTRY OF DEEDS, ETC. New Castle County Courthouse, Office of Recorder of Deeds STREET & NUMBER Deed Record Z , Volume 366 369, Court House CITY, TOWN STATE Wilmington Delaware 19801 REPRESENTATION IN EXISTING SURVEYS TITLE Survey of Delaware Historic Sites and Buildings DATE 1974 —FEDERAL X_STATE —COUNTY —LOCAL CITY, TOWN STATE Dover Delaware DESCRIPTION CONDITION CHECK ONE CHECK ONE —EXCELLENT —DETERIORATED —UNALTERED X.ORIGINALSITE 1LGOOD —RUINS FALTERED —MOVED DATE. _FAIR —UNEXPOSED DESCRIBE THE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL (IF KNOWN) PHYSICAL APPEARANCE Academy Square/ at the southeast corner of Main and Academy Streets, is a park, on the south side of which is the Academy of Newark building. -

Benjamin Franklin 1 Benjamin Franklin

Benjamin Franklin 1 Benjamin Franklin Benjamin Franklin 6th President of the Supreme Executive Council of Pennsylvania In office October 18, 1785 – December 1, 1788 Preceded by John Dickinson Succeeded by Thomas Mifflin 23rd Speaker of the Pennsylvania Assembly In office 1765–1765 Preceded by Isaac Norris Succeeded by Isaac Norris United States Minister to France In office 1778–1785 Appointed by Congress of the Confederation Preceded by New office Succeeded by Thomas Jefferson United States Minister to Sweden In office 1782–1783 Appointed by Congress of the Confederation Preceded by New office Succeeded by Jonathan Russell 1st United States Postmaster General In office 1775–1776 Appointed by Continental Congress Preceded by New office Succeeded by Richard Bache Personal details Benjamin Franklin 2 Born January 17, 1706 Boston, Massachusetts Bay Died April 17, 1790 (aged 84) Philadelphia, Pennsylvania Nationality American Political party None Spouse(s) Deborah Read Children William Franklin Francis Folger Franklin Sarah Franklin Bache Profession Scientist Writer Politician Signature [1] Benjamin Franklin (January 17, 1706 [O.S. January 6, 1705 ] – April 17, 1790) was one of the Founding Fathers of the United States. A noted polymath, Franklin was a leading author, printer, political theorist, politician, postmaster, scientist, musician, inventor, satirist, civic activist, statesman, and diplomat. As a scientist, he was a major figure in the American Enlightenment and the history of physics for his discoveries and theories regarding electricity. He invented the lightning rod, bifocals, the Franklin stove, a carriage odometer, and the glass 'armonica'. He formed both the first public lending library in America and the first fire department in Pennsylvania. -

A Political Biography of John Witherspoon from 1723-1776

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 1979 A political biography of John Witherspoon from 1723-1776 John Thomas anderson College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the European History Commons, and the Social and Behavioral Sciences Commons Recommended Citation anderson, John Thomas, "A political biography of John Witherspoon from 1723-1776" (1979). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539625075. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-tdv7-hy77 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A POLITICAL BIOGRAPHY OF JOHN WITHERSPOON * L FROM 1723 TO 1776 A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Department of History The College of William and Mary in Virginia In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts *y John Thomas Anderson APPROVAL SHEET This thesis is submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Author Approved, September 1979 John Michael McGiffert (J ^ j i/u?wi yybirvjf \}vr James J. Thompson, Jr. To my parents TABLE OF CONTENTS Page DEDICATION....................... ill TABLE OF CONTENTS ..................................... iv ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ............................................... v ABSTRACT........... vi INTRODUCTION................. 2 CHAPTER I. "OUR NOBLE, VENERABLE, REPUBLICAN CONSTITUTION": JOHN WITHERSPOON IN SCOTLAND, 1723-1768 . ............ 5 CHAPTER II. "AN EQUAL REPUBLICAN CONSTITUTION": WITHERSPOON IN NEW JERSEY, 1768-1776 37 NOTES . -

Pennsylvania Magazine of HISTORY and BIOGRAPHY

THE Pennsylvania Magazine OF HISTORY AND BIOGRAPHY Mapping Pennsylvania's Western Frontier in 1756 ARTOGRAPHERS HAVE LONG RECOGNIZED the French and Indian War (1754-63) as a territorial conflict between France and Great CBritain that, beyond producing profound political resolutions, also inspired a watershed gathering of remarkable maps. With each nation struggling to ratify and advance its North American interests, French and English mapmakers labored to outrival their "opposite numbers" in drafting and publishing precise and visually compelling records of the territories occupied and claimed by their respective governments. Several general collections in recent years have reproduced much of this invaluable North American cartographic heritage,1 and most recently Seymour I. Schwartz has brought together in his French and Indian War, 1754—1763: The Imperial Struggle for North America (1994) the great, definitive charts of William Herbert and Robert Sayer, John Mitchell, Lewis Evans, Jacques Nicholas Bellin, John Huske, Jean Baptiste Bourguignon d'Anville, Robert de Vaugondy, John Rocque, and Louis d'Arcy Delarochette, many of which 1 See, for example, John Goss, The Mapping of North America (Secaucus, N.Y., 1990); The Cartography of North America (London, 1987-90); and Phillip Burden, The Mapping of North America: A List of Printed Maps, 1511-1670 (Rickmansworth, England, 1996). THE PENNSYLVANIA MAGAZINE OF HISTORY AND BIOGRAPHY Vol. CXXIII, Nos. 1/2 (January/April 1999) 4 JAMES P. MYERS JR. January/April were published in 1755 (the so-called "year of the map") as opening cartographic salvos in the French and Indian War. Schwartz also offers a brief chronological account of the war.