A Political Biography of John Witherspoon from 1723-1776

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Journal of the Presbyterian Historical Society

JOURNAL OF tHE Presbyterian Historical Society. Vol. I., No. 4. Philadelphia, Pa. June A. D., 1902. THE EARLY EDITIONS OF WATTS'S HYMNS. By LOUIS F. BENSON, D. D. Not many books were reprinted more frequently during the eighteenth and the first half of the nineteenth century than the Hymns and Spiritual Songs of Isaac Watts. Few books became more familiar, and certainly but few played a greater part in the history of our American Presbyterianism, both in its worship and in its strifes. But with all this familiarity and multiplica tion of editions, the early history, textual and bibliographical, of the hymns has remained practically unknown. This is ac counted for by the fact that by the time interest in such studies began to be awakened, the early editions of the book itself had disappeared from sight. As long ago as 1854, Peter Cunningham, when editing the Life of Watts in Johnson's Lives of the Poets, stated that "a first edition of his Hymns, 1707, is rarer than a first edition of the Pilgrim's Progress, of which it is said only one copy is known." The second edition is not less rare. The Rev. James Mearns, assistant editor of Julian's Dictionary of Hymnology, stated (The Guardian, London, January 29, 1902) that he had never seen or heard of a copy. Even now the British Museum possesses nothing earlier than the fifth edition of 1716. It has (265 ) THE LOG COLLEGE OF NESHAM1NY AND PRINCETON UNIVERSITY. By ELIJAH R. CRAVEN, D. D., LL, D. After long and careful examination of the subject, I am con vinced that while there is no apparent evidence of a legal con nection between the two institutions, the proof of their connec tion as schools of learning — the latter taking the place of the former — is complete. -

Preaching of the Great Awakening: the Sermons of Samuel Davies

Preaching of the Great Awakening: The Sermons of Samuel Davies by Gerald M. Bilkes I have been solicitously thinking in what way my life, redeemed from the grave, may be of most service to my dear people ... If I knew what subject has the most direct tendency to save your souls, that is the subject to which my heart would cling with peculiar endearment .... Samuel Davies.1 I. The "Great Awakening" 1. The Narrative It is customary to refer to that time period which spanned and surrounded the years 1740-1742 as the Great Awakening in North American history. The literature dedicated to the treatment of this era has developed the tradition of tracing the revival from the Middle Colonies centripetally out to the Northern Colonies and the Southern Colonies. The name of Theodorus Frelinghuysen usually inaugurates the narrative, as preliminary to the Log College, its Founder, William Tennent, and its chief Alumni, Gilbert Tennent, and his brothers John, and William Jr., Samuel and John Blair, Samuel Finley and others, so significantly portrayed in Archibald Alexander’s gripping Sketches.2 The "mind" of the revival, Jonathan Edwards, pastored at first in the Northampton region of New England, but was later drawn into the orbit of the Log College, filling the post of President for lamentably only three months. Besides the Log College, another centralizing force of this revival was the “Star from the East,” George Whitefield. His rhetorical abilities have been recognized as superior, his insight into Scripture as incisive, and his generosity of spirit boundless. The narrative of the “Great Awakening” reaches back to those passionate and fearless Puritans of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, who championed biblical and experiential religion as the singular remedy for a nation and a people clinging to forms and superstitions. -

James Madison, John Witherspoon, and Oliver Cowdery: the Irsf T Amendment and the 134Th Section of the Doctrine and Covenants Rodney K

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Brigham Young University Law School BYU Law Review Volume 2003 | Issue 3 Article 3 9-1-2003 James Madison, John Witherspoon, and Oliver Cowdery: The irsF t Amendment and the 134th Section of the Doctrine and Covenants Rodney K. Smith Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.byu.edu/lawreview Part of the Christianity Commons, First Amendment Commons, and the Legal History Commons Recommended Citation Rodney K. Smith, James Madison, John Witherspoon, and Oliver Cowdery: The First Amendment and the 134th Section of the Doctrine and Covenants, 2003 BYU L. Rev. 891 (2003). Available at: https://digitalcommons.law.byu.edu/lawreview/vol2003/iss3/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Brigham Young University Law Review at BYU Law Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in BYU Law Review by an authorized editor of BYU Law Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SMI-FIN 9/29/2003 10:25 PM James Madison, John Witherspoon, and Oliver Cowdery: The First Amendment and the 134th Section of the Doctrine and Covenants ∗ Rodney K. Smith A number of years ago, as I completed an article regarding the history of the framing and ratification of the First Amendment’s religion provision, I noted similarities between the written thought of James Madison and that of the 134th section of the Doctrine & Covenants, which section was largely drafted by Oliver Cowdery.1 At ∗ Herff Chair of Excellence in Law, Cecil C. -

Fea on Morrison, 'John Witherspoon and the Founding of the American Republic'

H-New-Jersey Fea on Morrison, 'John Witherspoon and the Founding of the American Republic' Review published on Saturday, April 1, 2006 Jeffry H. Morrison. John Witherspoon and the Founding of the American Republic. Notre Dame: University of Notre Dame Press, 2005. xviii + 220 pp. $22.50 (cloth), ISBN 978-0-268-03485-6. Reviewed by John Fea (Department of History, Messiah College) Published on H-New-Jersey (April, 2006) The Forgotten Founding Father? Americans love their "founding fathers." As most academics continue to write books that address questions related to race, class, and gender in early America, popular historians and writers (and even a few rebellious academics such as Joseph Ellis or H.W. Brands) make their way onto bestseller lists with biographies of the dead white men who were major players in America's revolutionary struggle. These include David McCullough on John Adams, Ronald Chernow on Alexander Hamilton, Ellis on George Washington, and a host of Benjamin Franklin biographies (recent works by Walter Isaacson, Edmund Morgan, Gordon Wood, Brands, and Stacy Schiff come to mind) written to coincide with the tercentenary of his birth. One of the so-called founding fathers yet to receive a recent full-length biography is John Witherspoon, the president of the College of New Jersey at Princeton during the American Revolution and the only colonial clergyman to sign the Declaration of Independence.[1] Witherspoon was a prominent evangelical Presbyterian minister in Scotland before becoming the sixth president of Princeton in 1768. Upon his arrival, he transformed a college designed predominantly to train clergymen into a school that would equip the leaders of a revolutionary generation. -

History of Neshaminy Presbyterian Church of Warwick, Hartsville

HISTORY shaming ;jr^slrgtiriHn :yjturrh v7".A.:E^-^Arioic, HARTSVILLE, BUCKS COUNTY, PA. 17^6-187^. BY • REV. DfX. TURNER. PUBLISHED BY REQUEST OF THE SESSION. PHILADELPHIA : CULBERTSON & BACHE, PRINTERS, 727 JaYNE StREET. 1876. o o CO TABLE OF CONTENTS. PAGE. ' Correspondence, • ' ^}. ^i" Succession of Pastors, .... xv • • • • Preface, . • f CHAPTER I. EARLY SETTLEMENT. Jamison's Location of Neshaminy Church.—Forks of Neshaminy.— Corner.—Founding of the Church.—Rev. P. Van Vleck.—Deeds and yiven by WiLiam Penn.—Holland Churches at Feasterville Richborough.—Bensalem.—Few Presbyterian Churches.—The Scotch Irish. ....•• CHAPTER II. REV. WILLIAM TENNENT. Mr. Tennent's birth and education.—His ordination in the Episco- Presbyterian pal Church.—Marriage.—He unites with the Church.—Reasons for his change of ecclesiastical relation.— Takes Residence at Bensalem, Northampton and Warminster.— " Rev. charge of the Church at Neshaminy.—The Old Side."— Grave George Whitefield visits Neshaminy.—Preaches in the § Yard.—" Log College." CHAPTER III. SONS OF REV. WILLIAM TENNENT. N. J., and Rev. Gilbert Tennent.—His pastorate at Kew^ Brunswick, character. Rev. in Philadelphia.—His death and burial.—His William Tennent, Jr.—Education.—Residence in New Bruns- wick.—The trance.—Apparent death and preparation for burial. —His recovery.—Account of his view of Heaven.—Settlement Settlement at Freehold, N. J.—Death. Rev. John Tennent.— early age. Rev. at Freehold.—Usefulness.—Death at an Charles Tennent—Ordination at Whiteclay Creek, Delaware.— with the Residence at Buckingham, Maryland.—His connection "New Side."—Mrs. Douglass. -Rev. William M. Tennent, 19 D. D. — IV CONTENTS. CHAPTER IV. ALUMNI OF LOG COLLEGE. Rev. Samuel Blair.—Settlement at Shrewsbury, N. -

Charles Coleman Sellers Collection Circa 1940-1978 Mss.Ms.Coll.3

Charles Coleman Sellers Collection Circa 1940-1978 Mss.Ms.Coll.3 American Philosophical Society 3/2002 105 South Fifth Street Philadelphia, PA, 19106 215-440-3400 [email protected] Charles Coleman Sellers Collection ca.1940-1978 Mss.Ms.Coll.3 Table of Contents Summary Information ................................................................................................................................. 3 Background note ......................................................................................................................................... 5 Scope & content ..........................................................................................................................................6 Administrative Information .........................................................................................................................7 Related Materials ........................................................................................................................................ 7 Indexing Terms ........................................................................................................................................... 7 Bibliography ................................................................................................................................................9 Collection Inventory ..................................................................................................................................10 Series I. Charles Willson Peale Portraits & Miniatures........................................................................10 -

Church Will Present- Tdrug-- Abuse Movie

SOUTH BRUNSWICK, KENDALL PARK, NEW JERSEY, APRIL 2, 19.70 Newsstand 10c per copy Two suits have been filed in ~stffl5tlall5rTrrtpair thedntent and- ~ The doctrine "of res judicata fer undue hardship if he could" the Superior Court of New purpose of the zone plan and states that-a matter already re not uso the premises for his Jersey against South Brunswick zoning ordinance. solved on its merits cannot be work, in which he porforms Township as the result of zon litigated , again unless the matter light maintenance : and minor The bank contends further has been substantially changed. ing application decisions made that the Township Committee repairs on tractor-trailer at the Feb. 3 Township Commit usurped the function of the Mr. Miller contends that in trucks used to haul material tee meeting^ Board of Adjustment by con failing to approve the recom for several concerns. ducting Wo separate- public mendation of the Board of Ad The First National Bank of justment and in denying the ap The character of existing Cranbury has filed a civil ac hearings of its own in addition to the one'held by the Board of Ad plication, the Township Com uses in surrounding properties tion against the, township, the is in keeping with his property, justment. ... ............ : mittee was arbitrary, capri-_ Board of Adjustment and the -clous,- unreasonable; discrlm.- he contends, and special .rea First Charter—National—Bank- - Further, the bank says thew inatory, confiseatory-and con sons exist for grhntlngthe vari in an effort to overturn the' committee granted the variance trary to law. -

NJS: an Interdisciplinary Journal Summer 2017 269 John Witherspoon's American Revolution Gideon Mailer Chapel Hill: University

NJS: An Interdisciplinary Journal Summer 2017 269 John Witherspoon’s American Revolution Gideon Mailer Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, for the Omohundro Institute of Early American History and Culture, 2017 440 pages $45.00 ISBN: 978-1469628189 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.14713/njs.v3i2.92 On December 7, 1776, a British army brigade entered Nassau Hall, the primary building on the campus of the College of New Jersey at Princeton, and used it as a barracks and horse stable. The troops occupied this building, one of the largest in British colonial America, until George Washington’s Continental Army arrived on January 3, 1777 and drove them out of town at the Battle of Princeton. One British officer stationed in Nassau Hall would later write, “Our army when we lay there spoiled and plundered a good Library….” The damaged library belonged to Reverend John Witherspoon, the president of the college, who had fled Princeton for his own protection shortly before the arrival of British soldiers. Earlier in 1776, John Witherspoon sat in the Pennsylvania State House as a member of the New Jersey delegation to the Continental Congress. We know that he played a major role in Congress, but the destruction of his papers have prevented historians from writing the kinds of magisterial biographies of him like those published on George Washington, John Adams, Benjamin Franklin, or Thomas Jefferson. Historians do have, however, Witherspoon’s extensive published writings, allowing them to explore the depths of his religious and political thought. This is the approach that Gideon Mailer has taken in his new biography John Witherspoon’s American Revolution. -

Catalogue of the Alumni of the University of Pennsylvania

^^^ _ M^ ^3 f37 CATALOGUE OF THE ALUMNI OF THE University of Pennsylvania, COMPRISING LISTS OF THE PROVOSTS, VICE-PROVOSTS, PROFESSORS, TUTORS, INSTRUCTORS, TRUSTEES, AND ALUMNI OF THE COLLEGIATE DEPARTMENTS, WITH A LIST OF THE RECIPIENTS OF HONORARY DEGREES. 1749-1877. J 3, J J 3 3 3 3 3 3 3', 3 3 J .333 3 ) -> ) 3 3 3 3 Prepared by a Committee of the Society of ths Alumni, PHILADELPHIA: COLLINS, PRINTER, 705 JAYNE STREET. 1877. \ .^^ ^ />( V k ^' Gift. Univ. Cinh il Fh''< :-,• oo Names printed in italics are those of clergymen. Names printed in small capitals are tliose of members of the bar. (Eng.) after a name signifies engineer. "When an honorary degree is followed by a date without the name of any college, it has been conferred by the University; when followed by neither date nor name of college, the source of the degree is unknown to the compilers. Professor, Tutor, Trustee, etc., not being followed by the name of any college, indicate position held in the University. N. B. TJiese explanations refer only to the lists of graduates. (iii) — ) COEEIGENDA. 1769 John Coxe, Judge U. S. District Court, should he President Judge, Court of Common Pleas of Philadelphia. 1784—Charles Goldsborough should he Charles W. Goldsborough, Governor of Maryland ; M. C. 1805-1817. 1833—William T. Otto should he William T. Otto. (h. Philadelphia, 1816. LL D. (of Indiana Univ.) ; Prof, of Law, Ind. Univ, ; Judge. Circuit Court, Indiana ; Assistant Secre- tary of the Interior; Arbitrator on part of the U. S. under the Convention with Spain, of Feb. -

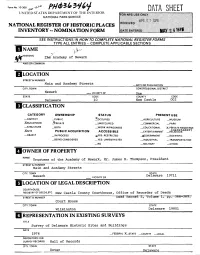

Hclassification

Form No. 10-300 ^O' 1 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES INVENTORY -- NOMINATION FORM SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOWTO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS TYPE ALL ENTRIES -- COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS I NAME HISTORIC .The"' Academy of Newark AND/OR COMMON LOCATION STREET & NUMBER Main and Academy Streets -NOT FOR PUBLICATION CITY. TOWN CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT Newark _ VICINITY OF One STATE CODE COUNTY CODE Delaware 10 New Castle 002 HCLASSIFICATION CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE —DISTRICT —PUBLIC .^OCCUPIED —AGRICULTURE —MUSEUM .XBUILDING(S) _3>RIVATE —UNOCCUPIED —COMMERCIAL —PARK —STRUCTURE —BOTH —WORK IN PROGRESS —EDUCATIONAL X-PRIVATE RESIDENCE JiSITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE —ENTERTAINMENT _ REGifc^S 6 —OBJECT _ INPROCESS -XYES: RESTRICTED -^GOVERNMENT —SCIENTIFIC —BEING CONSIDERED — YES: UNRESTRICTED —INDUSTRIAL —TRANSPORTATION _NO —MILITARY —OTHER: OWNER OF PROPERTY NAME Trustees of the Academy of Newark, Mr. James H. Thompson, President STREET & NUMBER Main and Academy Streets CITY, TOWN Delaware 19711 Newark VICINITY OF LOCATION OF LEGAL DESCRIPTION COURTHOUSE, REGISTRY OF DEEDS, ETC. New Castle County Courthouse, Office of Recorder of Deeds STREET & NUMBER Deed Record Z , Volume 366 369, Court House CITY, TOWN STATE Wilmington Delaware 19801 REPRESENTATION IN EXISTING SURVEYS TITLE Survey of Delaware Historic Sites and Buildings DATE 1974 —FEDERAL X_STATE —COUNTY —LOCAL CITY, TOWN STATE Dover Delaware DESCRIPTION CONDITION CHECK ONE CHECK ONE —EXCELLENT —DETERIORATED —UNALTERED X.ORIGINALSITE 1LGOOD —RUINS FALTERED —MOVED DATE. _FAIR —UNEXPOSED DESCRIBE THE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL (IF KNOWN) PHYSICAL APPEARANCE Academy Square/ at the southeast corner of Main and Academy Streets, is a park, on the south side of which is the Academy of Newark building. -

Blairs of Richmond, Virginia

BLAIRS OF RICHMOND, VIRGINIA THE DESCENDANTS OF REVEREND JOHN DURBURROW BLAIR AND MARY WINSTON BLAIR, HIS WIFE "Amo Probos" A:::¼::S:::1> Copyright, 1933 By ROLFE E. GLOVER, JR. BLAIRS OF RICHMOND, VIRGINIA Sarah Eyre Blair Glover 1861-1929 DEDICATION TO THE LOVED MEMORY OF SARAH EYRE BLAIR GLOVER THIS RECORD OF HER KINSPEOPLE BEGUN BY HER HUSBAND ROLFE ELDRIDGE GLOVER rs DEDICATED BY HER SON ROLFE ELDRIDGE GLOVER, JR. SARAH EYRE BLAIR GLOVER Sarah Eyre Blair Glover (186!-1929), born in Richmond, Virginia, was the eldest daughter of James Heron Blair and his wife, Jane Blair. While she was yet a small child, her father built his residence at the corner of Third and Cary Streets. In this house and its neighborhood Sarah Blair passed her earlier years. She attended local private schools. She early took part in the society life of Richmond, and was noted for her grace, beauty, and tactful manners. Of a very bright disposition, she pleased wherever she went. Gloom was foreign to her character. Pain she bore always with a silent fortitude. She never afflicted those about her with care and sorrow, but looked ever on the happier side. In 1885, at her father's residence, Sarah Blair married Rolfe Eldridge Glover, son of Samuel Anthony and Frances Eldridge Glover, neighbors of the Blairs. The young couple had been lovers for many years. Their mutual devotion lasted and deepened until death separated-for a very little while-their joy of companionship. To this couple one son was born, Rolfe Eldridge Glover, Jr. Rolfe Eldridge Glover at the time of his marriage was a rising man of business, and soon recognized as one of Rich mond's sterling citizens. -

Nassau Street, NW of Nassau Hall New Jersey Pitlcl^Siffcat ION ~™ Princeton University Princeton 08540 ___Mercer County C

Form 10-300 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR (July 1969) NATIONAL PARK SERVICE New Jersey COUNTY; NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES Mercer INVENTORY - NOMINATION FORM FOR NPS USE ONLY ENTRY NUMBER (Type all entries — complete applicable sections) C OMMON: Maclean House AND/OR HISTORIC: President's House (1756-1879) (Dean's House, 1879-1968) 12. LOG AT I pJN~ STREET AND NUMBER: Nassau Street, NW of Nassau Hall CITY OR TOWN: Princeton New Jersey Mercer pITlcL^sIFfcAT ION ~™ CATEGORY ACCESSIBLE OWNERSHIP STATUS (Check One) TO THE PUBLIC District [3$ Building Public Public Acquisition: J£X Occupied Yes: £3$ Restricted Site Q Structure Private || In Process II Unoccupied | | Unrestricted Q Object Both Q Being Considered Q Preservation work i n progress n NO PRESENT USE ( Check One or More as Appropriate) HI Agricultural F_7I Government D Pork [ 1 Transportation | | Comments | | Commercial [_) Industrial (JCXPrivate Residence [U Other (Specify) [Xl Educational [3] Military [31 Religious [~] Entertainment [3] Museum L~] Scientific OWNER'S NAME: Princeton University STREET AND NUMBER: CITY OR TOWN: Princeton 08540 New Jersey TEGALOESCRlFrToN™ COURTHOUSE, REGISTRY OF DEEDS, ETC: ________Mercer County Court House STREET AND NUMBER: South Broad Street CITY OR TOWN: Trenton New Jersey . REPRESENTATION IN EXISTING SURVEYS Historic American Buildings Survey (9 sheets and 2 photos) DATE OF SURVEY: 1935-36 Federa i State [ | County [_] Local DEF-'OSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS: Division of Prints and Photographs, Library of Congress STREET AND NUMBER: CITY OR TOWN: Washington D.C. 7, "DESCRIPTION (Check One) Exce llent Good Deteriorated CH Ruins dl Unexposed CONDITION (Check One) (Check One) Altered G Unaltered Moved QJ Original Site DESCRIBE THE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL (if known) PHYSICAL APPEARANCE Designed and constructed by Robert Smith of Philadelphia, the President's House, as built in 1756, was a brick two-story gable-roofed rectangular structure with a one-story polygonal bay extending from the west side near the southwest (rear) corner.